NZSC

In the nineteenth century there were a number of shipping companies which carried migrants from the UK to New Zealand, but because they were all sailing vessels those ships were small, unhealthy, dangerous and hungry. Many of the ships that managed to make it as far as NZ often arrived after a large number of migrants had died on passage. At the same time some of the shipping companies responsible for the migrant’s poor treatment dictated unfavourably to the NZ government. However, in their efforts to ensure the safety and well being of those European migrants, the New Zealand Shipping Company was formed in 1873. The company was funded by the Bank of NZ and an office was established in London. Since those early years the NZSC grew to be one of the most respected and well found of all the shipping company’s to sail under the red Ensign. In the following pages condensed from ‘The origins of the NZSC’ an insight is given on some of their sailing ships.

Punjaub

The first ship in which the NZSC had an interest was the 883 grt Punjaub. She was a small iron ship built in 1862 by Richardson of Stockton on Tees, owned by J. Knevitt & Co. of London, and chartered in 1873 by the newly formed New Zealand Shipping Company. Reduced from a ship to a three masted barque, she left London to load explosives at Gravesend in June 1873. Under the command of Captain Renaut she began the first episode of the NZSC by sailing towards Lyttleton, New Zealand. The little barque of just 182 feet in length carried 312 passengers, 200 of whom were British, 112 Danish, and a crew of 28 which made an on board total of 340 souls.

The Punjaub had a fine weather passage out as far as Cape Leeuwin, and up to that point had made good time. But when she was just 300 miles off the New Zealand coast, the little ship was confronted with heavy seas and strong gales which delayed her. That last 300 miles which took over a week to sail caused considerable discomfort to the migrants in particular.

Even though the NZSC had done its best under the circumstances, the conditions for that passage of 1873 was quite horrendous. any of the migrant passengers who were able to work were obliged to do so by their passage agreement in helping out in certain work details, those tasks included keeping their own accommodation in good order, holystoning the ‘tween decks, cleaning, cooking and even helping out on deck.

But the passage out to NZ was something of a disaster. Indeed, there were 28 deaths on board which included 20 children. Those fatalities were mainly due to measles, enteritis and typhus. On the ship’s arrival at New Zealand, the badly plagued Punjaub was put into quarantine at Ripa Island. But as the ship lay at anchor with her ‘Q’ flag flying, a further eight succumbed to the deadly diseases ravaging the ship. After being given a medical clearance the ship finally arrived at Lyttleton to discharge her cargo from London on 20th September 1873. Needless to say there wasn’t much cargo to unload when the ship tied up to Lyttleton, but what little there was came ashore in great celebration in what was to be the completion of the NZSC’s first venture into the shipping world.

The NZSC then began to spread its wings. Firstly an agency was set up in London by Mr Charles Wesley Turner of Christchurch, and then in October 1873, three ships named adamant of 815 grt, Columbus 744 grt, and Hope 812 grt were chartered. A month later a further 18 ships were chartered and two high class clipper ships were bought outright for service into the company. Those two ships were the Hindustan and Dunfillan, respectively renamed Waitara and Mataura.

The very first ship to be ordered specifically for the company was the Rakaia (above) which came from Blumers of Sunderland. During the course of 1873 three more iron hulled ships of sail came from the same builders, and in being named after New Zealand Rivers they were the Waikato, Waimate and Waitangi.

Mr Turner, the London agent, then busied himself by purchasing the Scimitar and Dorette later to be respectively renamed Rangitiki and Waimea. Those two were synonymous with the later ships of the company’s sailing vessels by being in the 1,100 ton bracket, each of which were able to carry over 300 passengers and migrants. The year of 1874 was one of massive proportions for the NZSC. Indeed, 37 ships were owned or chartered by the company running both ways with cargoes

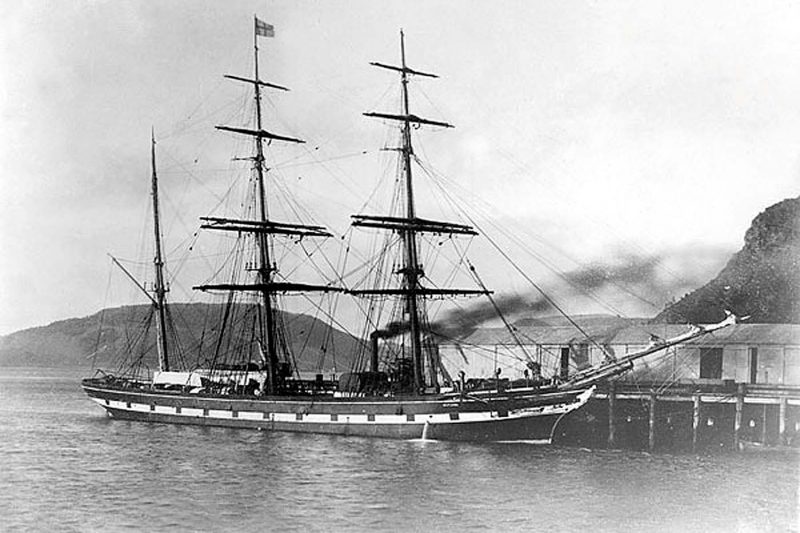

Hurunui

The Hurunui (above) was built at Jarrow on Tyne by Palmers and launched in 1875. But despite having a beautiful appearance, the Hurunui was the slowest ship in the NZSC fleet. Indeed, she seldom made a passage out to NZ in less than 100 days. In fact, it took 19 voyages for her to make the quickest passage of her career of 84 days from the UK to Lyttleton in 1891.

Her maiden passage under the command of Captain W.B. Boyd began at Gravesend on 24th November 1875. After 92 days she arrived at Wellington on 23rd February 1876, she had one saloon passenger and 186 steerage class.

The ship came to note when she was the first to enter and open the Lyttleton graving Dock in January 1883. On that historic day comes a report from The Lyttleton Times, “the Hurunui was the epitome of neatness and order and dressed in real holiday style. An arc of flags leading from the outer end of her jib boom extended over her masts and down to the gaff.” But six months after that great ceremony, the ship was involved in the fateful English Channel sinking of the Waitara on 24th June 1883. But at the enquiry the Hurunui’s captain and crew were exonerated and absolved of all blame. That fateful incident is described under the Waitara.

Captain Harry Cracroft had a trying experience on the Hurunui when she sailed from London on 14th June 1892 and arrived at Cardiff on the 22nd. After loading coal for Cape Town she sailed on the same day on the evening tide for Capetown, but in the Atlantic she was met with a series of South-westerly gales and heavy seas. Sails and spars were lost in the heavy weather which continued from the 6th to the 13th august, while the North-East and South-East trades proved poor. The Equator was crossed on 10th august, 39 days from Cardiff, and the Hurunui arrived at Capetown on 12th September. There she stayed until 29th October, or 32 days, to affect much needed repairs. After sailing for NZ she was met with strong South-East and North-Easterly winds which continued until Tasmania was sighted on 19th November. After passing Taiaroa Heads and then Otago on 1st December, the Hurunui was ordered on to Napier.

The passage from London which included the delay at Capetown took 175 days.

Despite having had a normal sailing career, there was one memorable passage the Hurunui made at the end of 1893 when on passage London to Algoa Bay, South Africa. Captain Plunket landed the pilot at Dungeness on 16th December but soon ran into heavy weather, which by the 20th December had reached hurricane force. As a result the ship was blown close to the French Coast. All hands were out continually setting and taking in sail while three of the sailors suffering injuries were incapable of work. Because it grew dark early at that time of the year, and to give the crew as much rest as possible, the captain stood off the French coast intending to wear ship in the daylight. At 4 pm however, Captain Plunket squared away and had just got the ship paying off when the Casquets Light suddenly appeared from under her bows. if he had continued to wear ship it would have meant him running right up onto the Casquets, a small cluster of dangerous rocks six or seven miles West of Alderney. A hasty glance at the chart revealed there was only one slim hope of escape, and that was to pass through the dreaded Alderney race. This strait separates the island of Alderney from the coast of Normandy, and in any kind of weather this can be a dangerous place. Indeed, there are 3½ and 4 fathom patches, numerous rocks, and to complicate matters further, there is a furious tide of anything from four to six and a-half knots.

The fully laden Hurunui was down to her marks, the sea was white with foam, and there were breakers everywhere while the ship’s decks were filled to the rails. With two men lashed to the wheel and storm sails set, the wonder is she lived through it at all. Three of her four boats were smashed, and the only one left was high up in the poop davits. The crew worked like Trojans, as indeed they must if they wished to come through it alive. The big danger was getting washed overboard and the miracle was that nobody did. However, with providence lending a hand the ship somehow got through the notorious Alderney race in the dark by 10pm. Captain Plunket gave great praise to his first and second officers who were both making their first voyage in those capacities. The first being Mr. McCarthy a native of Auckland, and the second being Mr. Seeley from Taranaki.

After the Hurunui had escaped from the nightmare of the Alderney race, she was given as much sail as she could carry and started off down the Channel. Captain Plunket went below for a much needed rest and was lying down ‘all standing’, a term used by sailors when they lie down in their sodden clothes. But shortly afterwards the captain was called to come up on deck by Mr. Seeley, a sail had been reported ahead and was in danger of being run down by the Hurunui. The mysterious stranger proved to be a small lugger almost on her beam ends and flying urgent signals of distress.

Mr. McCarthy was sent away in Hurunui’s last surviving boat, and Captain Plunket said later on that he never did see a boat being better handled in making a rescue of the three men on the wreck of the Bessie Waters. She was bound from Caen to Barnstaple in ballast. In the storm she had sprung a leak and rolled heavily causing her ballast to shift. But for the timely arrival of the Hurunui there would have been three more sailors to mourn. The master of the lugger expressed great astonishment at Captain Plunket’s feat of bringing a sailing ship of the Hurunui’s size through the Alderney race. “Old coaster as I am” said the lugger master, “I’d never dream of coming through the race without getting a pilot at Guernsey. As a matter of fact the Alderney race is never used by coasters because it’s far too risky.”

Lloyd’s Shipping gazette referred to “The gallant rescue by Captain Plunket,” and published a letter from the crew of the Bessie Waters expressing their gratitude to the captain for their timely rescue, and for landing them at Plymouth instead of taking them all the way to Algoa Bay.

But the Hurunui had poor luck during the whole of her passage to Algoa Bay. Her best day’s run was 213 miles, and only on four other occasions did she sail over 200 miles in 24 hours. it eventually took 76 days to make Algoa Bay, from where after unloading she was ordered to Otago Heads for orders and then onto Lyttelton for loading. The barque arrived at Lyttelton on 24th May and sailed again on 29th June for London.

The Hurunui and other ships built about the same time were particularly well furnished and comfortably fitted out for saloon passengers, but after about 1883, when the regular steamers started running, those who were not travelling for health reasons generally preferred steamers and that signalled the end for the sailing ships which went out of the passenger trade. The Hurunui was sold in 1895 to J. Lindblom and under the Russian flag she was renamed Hermes. She survived until 6th May 1915 until she was torpedoed off St. Catherines, IOW by a German submarine.

Piako

The second of the three ships built by Alexander Stephen of Glasgow was the 1,136 grt Piako (above) which was launched in December 1876. She sailed on her first voyage under Captain Fox on 5th February 1877 from London for Lyttelton via Plymouth with 290 migrant passengers and a crew of 40. She made that first voyage to New Zealand in 99 days, a reasonably good passage for the times.

On her second voyage Captain W.B. Boyd assumed command. Leaving Plymouth on 20th November 1877, Piako arrived at Port Chalmers on 12th February 1878 after being 76 days and 12 hours from port to port, a passage that was close to being a record. But Piako’s third passage out almost ended in disaster. Still under Captain Boyd she sailed on 11th October 1878 from Plymouth with 288 passengers, a crew of 40 and 1,050 tons of general cargo. After being at sea for a month on 11th November, and when she was 180 miles from Pernambuco, now Recife, smoke was reported to be coming through the fore hatch ventilator at 10.45am. In order to get to the seat of the fire the hatch tarpaulins were stripped, but a 20-foot flame leapt into the air and blew the hatch boards off. The foremost tier of cargo in the ‘tween deck was ablaze. The sailors tried to put the fire out by using the quickly rigged fire hose but to little effect. They then decided to batten down the hatch and get at the fire from another direction. They then tried to get at it from the married quarters below decks, but the dense and acrid smoke prevented them advancing very far.

There were 160 men among the migrant passengers, and whereas some of them acted bravely enough, there were others who were running around in a state of panic. The captain was therefore obliged to stand at the break of the poop with his pistol in hand. He was calming the women while ensuring that his orders were carried out. once the boats were lowered into the water there was a rush for them by some of the panic stricken rougher male characters, but whilst brandishing his pistol Captain Boyd gave the order of “Stand back everybody, women and children first.” amidst the thick palls of poisonous smoke rising skywards, everything possible was being done by the sailors to contain the blaze. At 2pm however, the cry of “Sail Ho!” came from the lookout and from then on the fearful situation settled down. The ship sighted turned out to be the Loch Doon which recognised Piako’s plight and steered towards her; but it still took 3 hours until 5pm for her to get close enough to transfer the passengers. The 786 grt Loch Doon was owned by D. & J. Sproat of Liverpool, and at the time of her assisting Piako, she was on charter to the NZSC. All the sailors volunteered to stay on board Piako to extinguish the fire and were on the pumps for 48 hours non stop. However, after having reached Pernambuco, Captain Boyd found his troubles were far from over when he discovered that smallpox was raging through the port with about 400 people dying daily. However, there was a small uninhabited island named Coconut Island about seven miles up the river from Pernambuco which was surrounded by a lot of sand and coconut trees. Captain Boyd hired the island and Piako’s passengers were landed there from the Loch Doon. But they had to endure a six week stay on the island while food and water was sent up from the under-repair Piako. Prior to that Captain Boyd and his crew had managed to save the ship. The fire was extinguished by scuttling her in the shallows to the level of her poop deck. When she was raised again very little damage was found to the ship’s hull, masts or rigging, but the fire had destroyed most of the cargo in the forward part of the hold, plus the greater part of the emigrant’s baggage, as well as the galley and donkeyengine. Piako finally arrived at Lyttelton on 5th March 1879 after necessary repairs had been made and after being 145 days out from Plymouth. An investigation was held at both Pernambuco and at Lyttelton, but the cause of the fire was never determined. On her very next outward passage from Plymouth the cry of “Fire!” was once again heard on the Piako. But this time the fire was quickly extinguished. it was later determined that a box of signal rockets stored in the lazarette had somehow ignited, probably from friction due to the heavy rolling in the roaring Forties while running her Easting down. This passage was her second best, arriving at Lyttelton on 16th January 1880 after being 85 days out of Plymouth.

Captain Boyd stayed on the Piako for six voyages and was by far her best commander. Her best homeward passage of 71 days was made under his command. He left the ship to take over the firm’s agency at Dunedin. Captain Sutherland was another of Piako’s well known commanders. He had her from 1885 until in the early 1892’s when she was sold to J. E. Schaffer & Co. of Elsfleth, Germany. However, eight years later in 1900 when bound to the Cape from Melbourne with supplies for the troops in the Boer War, the Piako was posted missing when almost 25 years old.

Wanganui

The last of the three ships to come from Stephen’s Glasgow yard for the NZSC, and the last sailing ship ever to be built for the company was the Wanganui (above) launched in January 1877. The Wanganui with Captain Watt in command left London via Gravesend for Lyttleton on the 20th March 1877. She anchored at The Nore for the night before weighing at first light on the 21st. The ship’s cook named David Fraser aged 28 who had succumbed to pneumonia died in the English Channel. The ship was obliged to put into Portland for a replacement while embarking 50 saloon and steerage class passengers. Leaving Portland on 28th March 1877 she arrived at Lyttleton on 1st July. William Barton a steerage passenger died of peritonitis on the 14th of April and was buried the same night. During her outward passage the Wanganui sailed 330 miles in 23½ hours whilst in the roaring Forties. Dr Hilliard, the medical officer reports that the general health of the passengers was good. In line with the company’s recreational system to reduce any boredom, several concerts and other entertainments were held during the passage.

Lyttleton Times – Voyage Account for the third outward passage 30 December 1878

The ship seen off Ocean Beach on the forenoon of 30th December proved to be the NZSC ship Wanganui. On reaching the Heads she was met by the smart little tug steamer Koputai, which after passing her towing line brought her up to the Powder Ground at 8 pm. She was boarded by the Customs officers and cleared in. Our old friend Captain Watt who is now in command of the Wanganui is the man who on the Celestial Queen brought the first shipment of salmon to this country. Captain Watt brings with him Mr Henderson as his chief officer, Mr Ferries as his second, and Mr Wilkinson as the third. It is needless to describe the passenger accommodation of this ship as it is the same as that of the Waipa, Otaki and Piako. She brings some 50 passengers, and carries a surgeon named Dr. Beard who after working his passage is about to settle in New Zealand. The Wanganui has also brought 1,950 tons of cargo and some 20 tons of explosive powder. When the latter has been discharged at the powder ground she will come up to the pier to discharge her general cargo. Dr. Beard reports the general health of the passengers to be good with just one case of sickness which resulted in death. The victim was Mr. James Paton aged 38 and was by trade a painter and a resident of Christchurch.

Mr. H. Hubbard who was later employed by the Union Steamship Company, entered the service of the NZSC in 1879 as an apprentice on the Wairoa, but on changing to the catering branch he joined the Wanganui in 1884 as her chief steward and made two trips in her. He states, “After discharging our outward cargo in 1884 we were sent to Napier to load for London but had to lie in Hawke’s Bay for over three months. On two occasions the ship had to weigh anchor and run out to sea for several days to ride out the strong Southerly gales. With Captain Adams we experienced very bad weather on the voyage back to the UK. Under Captain Watt I sailed again in the Wanganui from London in June 1887, but we were detained some days after being ready for sea owing to a fire breaking out on board the Orari which was lying alongside us. She was also ready for sea and should have sailed by the same tide as us. All hands were engaged during the night quelling the fire until the dock fire brigade arrived. The passengers who were on board were much concerned about their personal belongings while some of the Orari’s wreckage fell onto our decks. When we eventually sailed, the Wanganui had a fair run until rounding the Cape but then encountered hard Westerlies. On one occasion heavy seas broke on board and stove in the forward deck house, smashing the starboard bulwarks and the galley, during which two seamen and the cook were severely injured. After discharging the cargo at Wellington we were towed to Picton by the steamer Moa, but were detained there for over two months. We took a large number of sheep on board and returned to Wellington then sailed from that port just four days after the ill-fated Marlborough which disappeared with all hands. The Halcione was also at Picton, and we were informed that the Wanganui and Halcione were the first two large ships to load cargo for the UK. On arrival at London the Wanganui was sold and renamed Blenheim. I was transferred to the Orari, and sailed for Wellington in 1889.”

The Wanganui, did not make any record trips when in the NZSC, but did make better than average runs. Her best passage was to Lyttelton in 1878 under Captain Watt. This was accomplished in 80 days port to port. Her next best run of 84 days to Port Chalmers was in 1879 when she was also under Captain Watt. She ran until 1889 under the NZSC flag but was then sold to the Shaw-Savill Company. Renamed Blenheim she remained in the New Zealand trade until 1899 with her last and longest run of 122 days from Liverpool. on her arrival at Wellington during her last trip in 1899, Captain Colville who’d been in command of the Blenheim for six complete voyages stated, “it has been the most wearisome passage I have experienced for many years with violent and dreadful weather throughout the whole passage.” in 1903 she was sold to H.C.A. Miichelsen of Norway before being sunk by U-50 on 22nd February 1917, 30 miles SSW of Fastnet while on a voyage from Pensacola to Greenock with a cargo of pitch pine.

White Eagle

In 1850 Captain William Story Croudace married Elsie Stephen, she was the daughter of the Scottish shipbuilder Alexander Stephen who was also a ship owner. Two of the sailing vessels he operated were the White Eagle (above) and Corona. The 1,082 grt White Eagle which was to become the Pareora of the NZSC in 1878, signed her maiden voyage crew on 18th April 1855 at Glasgow and left the Clyde for Melbourne two days later. She was one of numerous ships that sailed between the UK, Australia, and New Zealand. The White Eagle carried 13 cabin and 49 steerage passengers as well as a crew of 42. In command was 34 year old Captain Croudace.

Born at Leeds in 1821 Captain Croudace had obtained his masters certificate at Dundee in 1849. The voyage on the White Eagle was his first to Australia, and from his log which is now held in the National archives of New Zealand, we can glean something of the trials and tribulations that both he and his crew as well as the emigrants endured during the passage. No doubt the journey was typical of many others in which there was heavy weather, men overboard and crews on the verge of mutiny.

White Eagle’s Crew consisted of: Master, Surgeon, 1st mate, 2nd mate, Carpenter, Bosun, Sail maker, 3 apprentices, chief cook, second cook, chief steward, second steward, assistant steward, Matron, assistant matron, schoolmaster, cabin boy, 20 able seamen and 3 boys.

Captain’s Log

20th April – South of the Tuskar, able Seaman John Lawson who was working on the starboard life boat fell overboard. The ship was hove to and a boat was quickly lowered; every effort was made to find him in the water but he was lost.

21st April – The chief steward was found to be incapable of his duties and demoted to second steward, his pay has been reduced to £2 per month.

22nd April – John ? Unable to perform his duties due to venereal disease. His pay has been stopped until he can work again.

23rd April – William ? Unable to perform his duties due to venereal disease. His pay has been stopped until he can work again. For the next five weeks the ship took a South Westerly course across the Atlantic, and judging by the lack of entries in the captain’s log there were no serious incidents. But on 26th May when off the coast of Brazil, the ship was hit by a terrific storm in 23S and 36W.

From The Melbourne Argus 16th August 1855 taken from the Captain’s log.

The White Eagle was struck by a heavy sea that unshipped the wheel and carried away the spokes. Helmsman William Devonshire who was lashed down was thrown over the wheel and sustained a serious scalp wound. He was conveyed to the mate’s cabin and the wound was sewn up by the surgeon. He did not return to duty for a month. Experienced a violent hurricane having the whole of the poop fittings washed away, and 4 feet of water in the saloon for several hours. All hands and passengers engaged in bailing out. The ship is built with 5 watertight compartments but there is 2½ feet of water in the main compartment. Every soul fore and aft has given up any hope of survival.

16th June – Again she was caught in a cyclone at 37S and 0W which filled her with water to the height of 4 feet on the deck, split all the sails, stove in a quarter boat and damaged the fore rigging. Captain Croudace made the decision to head towards South Africa for repairs and supplies. But on her arrival at Simon’s Bay trouble really came to a head with the crew. In the midst of Atlantic Ocean storms it had been a matter of life and death for all to work together. But the safety of port revealed the crew’s discontent.

28th June – At anchor in Simon’s Bay. The crew worked reluctantly and were very noisy causing great annoyance to the chief and second officer. They paid little attention to the orders given and one AB named John Bellamy hauled the ensign down, but when he was brought before me and rebuked he said he would do it again. I put him in irons. The whole crew left their work and came aft in a body, but most reluctantly turned to again when ordered.

29th June – For the peace of the ship I had able Seamen John Bellamy & John Fullarton taken ashore and discharged them before the magistrate.

30th June – Most of the crew were drunk kicking up a noise and making use of disgusting language until nearly 11 pm. They rendered themselves incapable of keeping the night anchor watch and that obliged the officers of the ship to keep it for them.

1st July – at 10 am. I called the men aft and explained to them the articles and again asked them if they would wash the decks down. They all refused. AB Griffiths said he would rather go to gaol stating it was unnecessary work. I replied saying I would stop a days pay from each of them and put them on bread and water if they refused. They said they did not care, and when I ordered them forward at 8pm they all refused to keep the anchor watch. James Johnstone an AB began disputing the right I had to make them keep a night watch. Samuel Hendry an AB refused to do any more duty.

John Sheasby AB who had rowed the master ashore absconded from the boat whilst waiting for his return. The day previous he had asked for his discharge and was willing to give up his wages, he said the crew had led him such a dog’s life he was feeling wretched and could no longer remain on the ship with them. Several of the crew found themselves serving six weeks in Simon’s Town Prison for the trouble they had caused. But with crew numbers made up again the ship set out for Australia. Making good progress and without further serious incident the ship arrived at Port Phillip Heads on 15th august 1855, 29 days out from Simons Town. She was brought in by the steam tug Lioness into Hobson’s Bay.

1st August – Steward Alexander Murray had permission to go ashore and return the next morning at 6am. He absconded having already sent his clothes ashore with the assistance of the steerage passengers.

18th August – Gilbert Preston the cook asked for permission to go ashore and buy a pair of boots. A two shillings sub was given for their purchase. He absconded.

21st August – James Gilmour King 3rd steward and John Russell Butcher were discharged by mutual consent.

24th August – able Seamen John Duncan, William Devonshire and Alexander Cheap deserted during the night taking their clothes with them. Notice was given at the Police office for their apprehension and a reward of two pounds was offered for each.

28th August – William McIntosh the Bosun, Peter Gifford and James Welsh able seaman deserted during the night.

1st September – apprentice Joshua Young had liberty to spend a week ashore with his uncle, but after remaining with them six days he absconded and was not found up to the date of the ship’s departure from Melbourne. It seems that even family ties matters not, Captain Croudace’s two nephews Alfred and William Jessop were serving as apprentices on the White Eagle.

2nd September – Robert Henderson the sail maker and Alfred Jessop an apprentice deserted taking a lighters boat. A two pounds reward is offered for their apprehension. Had Alfred told his brother William what he intended to do? Why did a boy of 16 decide to desert ship on the other side of the world leaving all he knew behind? It seems the reason was young Sarah Nixon a steerage passenger travelling with her parents. We know this because a little over a year later I heard that they were married, and 17 year old Alfred had suddenly become 21. After a few years in Melbourne they left for the Ballarat goldfields where Alfred would make his living in the mines. Did he ever see or hear from his brother or his family in England again?

None of the deserters had been recovered so their places were taken by Lascars and Europeans.

The White Eagle departed from Melbourne on 20th September 1855 and returned to London via Calcutta. She arrived there on 16th May 1856 which was 13 months after departing Glasgow.

In 1886, after being completed, Pareora was put up for sale and purchased the following year by J. Livingston. She was broken up in 1889.

Ten years later, Captain Croudace returned to Australia in 1866 on the 1,199 ton ship Corona which was carrying 300 convicts with 30 guards and their families to the Swan River Colony, later to become Perth. In charge of the convicts on that voyage was royal Navy Surgeon Superintendent William Crawford. His journal gives us an indication of the conditions onboard:

6th September – Surgeon Superintendent went ashore to inspect the prisoners at 1 pm. During his absence 98 convicts arrived on board from Chatham. One of the crew who was seized with cholera was sent on shore. Weighed anchor at 4am on 7th September on passage to Fremantle.

14th September – very rough weather all last night. Strong squall at 3am with many seasick. Wine issued for the first time.

15th September – Prisoner 7604 William Sharp very sick. His bedding & clothing was thrown overboard.

16th September – Prisoners 7811 Enoch Gibson and 7037 Alexander McCulloch suffering from diarrhoea with cramps and symptoms of cholera.

17th September – William Sharp departed this life.

20th September – Prisoner No 7564 Owen King suffering from choleric diarrhoea.

23rd September – Divine service in the prison. 11.15pm Enoch Gibson departed this life…wine issued to all hands.

17th October – very rough weather during the night. Most of the prisoners were sick. Wine issued to all at 1.20pm. Much rain today.

24th October – 3.15pm. The wife of guard Casey safely born a daughter… wine issued.

25th October – 6.30am. The wife of Sergeant Hughes delivered of a son.

4th November – 10.50am one of the sailors went overboard, a life buoy thrown out to him immediately by which he was supported until he was reached by the ships boat which had been lowered immediately.

8th November – 7.50 am. 7718 Thomas Hinson departed this life. 3.30pm Thomas Hinson was carried to the rail by his three mates.

25th November – a discovery indicated the resourcefulness of some of the convicts. This evening (on doing his usual rounds) the carpenter discovered several small holes bored through the adjacent deck planks that formed in the shape a square, evidently intended to make a hatch sufficiently large enough for the passage of a man’s body. on examining the upper surface of the ‘tween deck in the convicts quarters, not the least trace of a cut or abrasion of the plank could be seen, so ingeniously had the same been filled in with waste paper and soap, and only by pushing up a wire from below, could the place be found. It was situated under the bottom board of one of the convict’s beds. No doubt another day or two would have completed it and admitted the convicts into the hold. On questioning the men they denied all knowledge of it, but because of the serious nature, the two men occupying the berths over the place and the Captain of the Mess were selected by the Surgeon Superintendent for Corporal punishment, and at noon this was carried into execution as follows No 456 Hugh McGriskin 18 lashes. No 9311 George Egan 24 lashes. No 275 John Barker 24 lashes. The two latter were afterwards put into hand and leg irons.

23rd December – arrived at Fremantle 9.30am. The Controller general and Commandant arrived onboard and inspected the ship, and then made arrangements for the disembarkation of the prisoners and guards tomorrow commencing 6am.

After landing the convicts the Corona sailed on to Calcutta to pick up 433 Indian workers destined for the fields of Jamaica. But 14 died of them en route in what was a much higher death toll than amongst the previous convicts.

At a later date Captain Croudace’s became a ship owner. Amongst those ships were the Broomhall, the steel barques Procyon built in 1892, Castor 1886, Orion 1890, and the tanker Pollux 1887. He also had interests in the whaling vessels Mysanthean, Triune and Cornwallis, all of which were lost. Another of his vessels the St Enoch under the command of Captain Browse departed Dundee in March 1878 with two thousand tons of coal en route for Calcutta. Last sighted off Dover she and her 33 hands were never seen again. That and the fate of his own two sons will remind us of the enormous toll of lives and ships taken by the sea in those days. His sons were both mariners who died at sea, Captain John Stephen Croudace of the Orion in 1897 and Lawrence Croudace on rover in 1886. Captain Croudace having survived many years at sea was still working to his last day, but died on a Dundee train at the age of 73.

City Of Perth

In the days of sail there were some ships that experienced some notable incident or other which placed them in the pages of history, and one of those ships which was firstly named City of Perth was later to become the Turakina. Indeed, there were two ‘notable incidents’ regarding that ship and one under each of her two names. The first of these was when she was sailing as the City of Perth, a fully rigged ship built by Charles Connell of Glasgow in 1868 for George Smith’s City Line. She grossed 1,189 tons and had a length of 232 feet. The ship traded to India in the first few years, but under Captain Beckett was diverted to Australia in 1873. Two years later in 1875 Captain Warden took over and after making several successful wool runs to Melbourne, the Glasgow registered ship was put on the London berth in 1881 to load for Canterbury. Captain McDonald then took command, and on leaving the UK on 4th December 1881 he reached his New Zealand destination after a 97 day run on 12th March 1882. After discharging her general cargo she went to Timaru to load wheat for the UK, but it was there that she fell victim to one of New Zealand’s notorious gales.

As she lay at anchor on 13th May the City of Perth had almost finished loading in Caroline Bay of Timaru. But a gale suddenly sprung up and extra cable was paid out to ensure the ship didn’t drag. The velocity of the wind increased and even more chain was laid out. The ship was on a lee shore and any thought of escape to the open sea was by that time out of the question. As well as the gale that screamed through the rigging huge seas thundered over the ship and crashed onto the nearby beach. also at anchor and quite close to the City of Perth was the Ben venue, a smaller ship that was moored to two anchors, but even though she paid out as much cable as possible and both ships took every precaution, they were battered all through the night by the ferocious gales. The 1,000 ton Ben venue which had been in the bay since 5th May was presently discharging 500 tons of boxed off coal she’d brought from Newcastle NSW. Owned by Watson Brothers of Greenock she was under the command of Captain ‘Mad McGowan’ as her sailors affectionately called him. But there was nothing mad about ‘Mad Mac, he was an excellent sailor and a most popular master with his crew. Indeed, so good a seaman was he, that if his ship was out in the open sea facing the same elements of weather he wouldn’t have had a problem. The Ben venue’s shifting boards in the hold had been removed to discharge the cargo, but what was left of the coal shifted in the violent rolling during the night and that gave the ship a heavy list. There was no let up in the atrocious weather of screaming gales and thundering seas and eventually that weather won the battle. At 8 am one of her anchor cables carried away. The spare anchor was immediately made ready and a steel wire rope known as the insurance wire was bent on, but as frantic efforts were made to get it over the side, the other anchor cable which was out to its bitter end (last link) also parted. The sailors had been down in the hold for most of the night trying to keep the coal in trim, but after the second anchor had been lost, and the port side boat ripped out of its chocks and smashed to firewood, the old Man gave the dreaded order to abandon ship as she continued to drag towards the lee shore. The starboard boat was launched with great difficulty and after being tossed about in the raging sea was driven towards the City of Perth where the escapees managed to board. Captain McGowan took the gig boat and managed to land on the beach, while at the same time the wire rope which had held his ship’s third anchor also carried away. With all her ground tackle gone the unmanned Ben venue was driven ashore and became completely wrecked.

The City of Perth was not faring any better. In the boiling seas Captain McDonald her captain tried to get a boat ashore but it capsised on hitting the water. The second mate and carpenter were drowned while the first mate suffered a broken leg. On the beach great efforts were made by a large number of volunteer rescuers to launch the shore lifeboat. Captain Mills the harbourmaster disapproved of the City of Perth abandoning as the weather was starting to ease. Nevertheless he took a 27 foot whaler and with the help of six men at the oars he went to the rescue. While at the same time Captain McGowan who had escaped from the Ben venue took his own ship’s gig, and in company with the shore lifeboat set out through the thundering seas in an attempt to rescue those on board the City of Perth.

But with Captain Mills at the tiller the whaler capsized in the boiling surf and five of her crew including himself were drowned. Shortly afterwards the City of Perth’s crew, and those rescued from the Ben venue escaped the ship and managed to reach the beach. The last of the City of Perth’s moorings, namely the wire rope on the spare anchor then parted, and amidst the howling gale and huge breakers the ship was driven onto the beach stern first.

The City of Perth was later refloated and towed to Port Chalmers for dry docking and repairs. Eleven months after that dreadful gale which had almost wrecked her, she loaded a cargo of wool at Invercargill on the Bluff and then sailed for London on the 13th April 1883. In command was Captain McFarland who made the run home via the Horn in 86 days.

The hull of the Ben venue and her cargo was insured for £13,500. What was left of the wreck was sold for £150 after some portions had been salved.

Turakina

After a thorough refit in London the City of Perth was purchased by the NZSC. She left London on 24th October 1883 with Captain Power in command, and sailed for Auckland under her new name of Turakina. After an 84 day passage she arrived in the Waitemata river of Auckland on 17th January 1884.

On the following voyage in 1885 the Turakina under Captain Power had a bad time of it after sailing on 9th March when she was homeward bound from Port Chalmers towards London. It was hard gales all the way to Cape Horn, and then when good weather was expected in the South Atlantic she ran into a ferocious hurricane on 11th April. Sails were blown out, a boat was smashed and part of the bulwarks and the top rail were ripped off in the murderous seas. But she came through it all and crossed on 3rd May. After taking steam in the Channel she arrived in London on 11th June after a 94 days passage.

In the following years the Turakina made many successful runs to New Zealand. Her best effort being from London in 1886 when she sailed on 30th October. After taking migrants at Plymouth she crossed The Line twenty days later, rounded the Cape on 22nd December, passed Tasmania on 18th January, and three days later was abreast of the Snares before arriving at Port Chalmers on 24th January.

However, after that there were several occasions on both the homeward and outward runs in which the Turakina encountered heavy weather. On one occasion during a hurricane in 1888 when the ship was bound from London towards Port Chalmers, the ship was pooped with a mountainous sea and both the first mate and the helmsman were washed overboard and lost.

In 1889 the Turakina was fitted with Haslam’s refrigerating dry air machinery. She then went to Hamburg from where she made a fine run to Port Chalmers. Leaving Bishop’s rock behind her on 25th November, she crossed The Line on 12th December after being only seventeen days out. She rounded the Cape on 6th January, passed Tasmania on the 28th, and anchored at Port Chalmers on the 5th February. That passage was 84 days port to port or 72 days land to land. Her best day runs in the Southern ocean were 312, 310 and 302 miles.

Turakina also made a good run to Wellington in 1890. On that occasion she sailed from London on 11th October and had fine weather to The Line which was crossed after being twenty-eight days out. She passed Cape Leeuwin on 20th December, Tasmania six days later, and Cape Farewell on 2nd January, thus making the run in 83 days from Beachy Head.

Sailing as the City of Perth, her stranding on 14th May 1882 at Timaru went down in maritime history. But her second entry into the annals of the sea occurred on 14th February 1895, when sailing as the Turakina and is described as follows.

Much has been written and many a picture painted on sailing ships passing steamers; the most famous of which, was when the Cutty Sark passed the 16 knot RMS Britannia in the middle watch of 26 July 1889. Sailing ships had often given steamers the ‘go by’ but these were normally paddle wheelers or seven knot screw ships. However, when those ships were 14 knot auxiliary steamers carrying passengers and mails a different perspective emerges. It has been said that many a sailing ship master would sacrifice his masts, yards and sails to leave a mail boat in his wake.

However, due to the passage of time certain aspects of history appears to change in one way or another, and such variations of a subject can at times leave readers in doubt. The reference which follows is in regard to the NZSC ship Turakina overtaking the RMS

Ruapehu of the same company on 14th February 1895 in the Southern ocean. There are at least two oil paintings made by noted artists depicting the famous sea passing, and whereas the proud Captain Hamon of the Turakina makes no secret of the fact, Ruapehu’s master Captain Findlay claims it was his ship that did the overtaking by passing the Turakina. He even sent the following telegraph to the United Press in London describing the incident:-

But Captain Hamon’s description of the event varies considerably with Captain Findlay’s and is printed below:-

On 14th February 1895 the Turakina was running her Easting down in 46 South and 68 East, while her French speaking master who hailed from Jersey had his ship tearing through the roaring Forties. At 9 am an auxiliary steamer was sighted fine on the port bow, and not knowing it was the 4,219 grt RMS Ruapehu from the NZSC, Capt. Hamon ordered all sail to be crowded on.

On board the Ruapehu meanwhile, on passage from Cape Town to Wellington via Hobart, she was at the time supposed to be making 13 knots on the log. Second Mate Mr Turner was on the bridge after having just relieved Third Mate Mr Tosswill who had gone below for his breakfast. But while the second mate on the bridge, and his look-out in the crow’s nest, with their eyes peeled looking ahead, Captain Findlay who came up to the bridge informed Mr Turner, in great disbelief, that a sailing ship was approaching fast from astern. Indeed, at such a speed an officer of the watch could hardly be expected to be looking for anything abaft the beam, and the same would apply to the lookout in the crow’s nest.

Rapid messages were conveyed to the engine room and shortly afterwards coal was being furiously thrown into the stokehold fires to attain maximum speed. Indeed, no captain of any steamer would want to suffer the indignity of being overhauled by a sailing ship, and especially if he was the victim. At that particular time the Ruapehu had her fore course and topsail set, but for fear of being humiliated by the ship coming up from astern, her top-gallant were quickly sheeted home. But any increase in speed made no difference as Turakina continued reducing the distance.

Indeed, three hours later at noon when the Turakina had every stitch of canvas up, she tore through the water at a supposed 17 knots and finally caught up with the supposedly 14 knot mail boat. She then took her mizzen royal and t’gallant in. With no more than a ship’s length between them, the Turakina passed the steamer on her lee side and left her astern.

No doubt the crew of the sailing ship trailed a rope over the stern inviting the steamer to take a tow. Indeed, such was the custom of a sailing ship when overtaking one of steam. So close were the two ships when the passing took place, that the mailboat’s passengers crowded the rails to watch in disbelief at what was to be the most notable event of the passage. So close were the two ships to each other that the faces of individuals could be clearly seen.

The Turakina then held her own against the illustrious steamer until 9.30 pm. at noon on the following day the log revealed the Ruapehu had run 315 miles at 13.1 knots. At midnight the wind came from aft and next morning the Turakina was out of sight. The mate of the mail boat said that seeing sail beat steam was a wonderful experience, and when he was well out of his captain’s earshot he said he was ‘glad to see it.’ The Turakina held her own for fourteen days and covered the 5,000 miles between the meridians of the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Leeuwin in sixteen days, her best runs being 328, 316 and 308.

One point of note in that historic ‘sail beats steam’ passing, was the telegraph from the Ruapehu to the United Press which states that she passed the Turakina and the Santa. It seems strange that such a fast ship passed only two other vessels on the passage. Because between Cape Town and Wellington, in those years there were scores of ships of both sail and steam sailing across the Southern ocean, so why was Captain Findlay’s emphasis on Turakina? On the other hand, the 17 knots claimed by Captain Hamon seems to be rather ambiguous. None of the ZNSC sailing ships were ever capable of making such a speed.

But on her next trip in 1896 when captains were changed, the Atlantic weather caused so much damage to the Turakina that Captain Power had to put into Rio de Janeiro for repairs. An even worse experience occurred in 1898 under Captain Fox when she left London for Port Chalmers on 28th April. The bad weather started in the Channel and Captain Fox was compelled to take her into Portland Bay to shelter. Sailing again on 6th May she then had a most trying experience all the way to the Cape where she met continuing heavy gales and mountainous seas.

After passing the equator on 4th June the Cape was reached on 4th July 1898, but there she was confronted by a strong northeast gale which gradually increased to force ten and beyond. The ship was constantly being battered by heavy seas which smashed the skylights, flooded the saloon and carried away the poop rail on the starboard side. The gale continued with great ferocity and everything movable on deck was swept away. During the height of the storm it was found necessary to lash both men to the wheel in order to keep them from being swept away, while oil bags were constantly put out both fore and aft.

The seas were by then terrific, breaking over the ship and washing out the petty officers’ deck-house compartment, sweeping through the galley, the sailor’s foc’sle deck-house and doing great damage everywhere. The poop deck skylights and rails, topgallant rails and bulwarks had all gone overboard, and the force of the gale almost swept the captain, the officer of the watch and the two men at the wheel overboard. As there was no sign of the storm abating, Captain Fox managed to heave to under bare poles in a great feat of seamanship. This however, was only accomplished with the aid of a plentiful supply of oil that temporarily moderated the raging seas. The crew urged Captain Fox to make for port as they considered the ship was not in a fit state to proceed. But things were so bad he didn’t need much coaxing and made Algoa Bay where he arrived on 9th July.

After repairing the damage she sailed again on 18th September 1898 and was met with west and south-west winds across the Southern ocean. After passing Cape Leeuwin the ship again encountered severe south-east gales. She passed the Snares on 3rd November and arrived at Port Chalmers 192 days after leaving London, the same time the whole of a normal voyage from London and back would have taken. On her return to London the refrigeration machinery was removed and in 1899 the one time pride of the sailing fleet was sold to a. Bech of Norway. The new owner cut her down to a barque rig and renamed her Elida. Little is known of her after that, except for her being used as a lumber ship in the Baltic. According to Lloyds of London she was broken up in 1914.

Orari

Like her other sister-ships and at a cost of £20,000, the Orari was the second of the five ships to be built by Palmers at Jarrow on Tyne. She was named after the small river Orari of Canterbury, which is about 12 miles NE of Timaru. The Orari came off the stocks in July 1875. Similar in size to the rest of the fleet she was 1,054 grt with her measurements being 204 x 34 x 20. During the course of her career for the NZSC she completed almost 20 voyages, but like all the others in the fleet she was not noted as being a fast ship. On her maiden voyage under Captain Fox however, she made what was to be her quickest passage out to Lyttleton in 91 days dock to dock, or 84 days land to land. On arrival Captain Fox told the Lyttleton Times that Orari was a magnificent ship and much faster passages could be expected in time to come. But they never did. Nevertheless, the newspaper wrote an excellent account of the ship and its accommodation.

The Star, Thursday 13th & 14th January 1876

Ship Orari, from London. This fine new iron clipper which is owned by the New Zealand Shipping Company and commanded by Captain Fox, arrived here yesterday evening after a passage of 92 days, 84 from land to land. No sickness occurred during the voyage. The Orari brings a large number of passengers including the Hon. John Hall, late Postmaster-General of New Zealand and his family. This gentleman took charge of a box of bumblebees from Plymouth but it is feared that despite the attention paid to them they are all dead. The design of the ship has been made by Captain Ashby, the Marine Superintendant of the Company in England. Her length is 204ft over all, 34ft breadth of beam, and 20ft depth of hold, and her saloon affords comfortable accommodation for eighteen passengers. On this her first voyage the Orari has not brought out any immigrants, but has on board fiftyfive first and second class passengers. The whole of the arrangements for the passengers on board have been carried out under the superintendence of Mr W. W. Jones, the despatching officer of the Company. Orari’s deck is lumbered up with sheep and cattle pens. There are a number of exceedingly fine Lincoln rams and some Romney Marsh rams. There is a fine Alderney cow and a Berkshire boar. In addition there was on board a Tristan da Cunha sheep and pig, which were taken on board at the Island. The sheep are the property of Mr J. Grigg and L. Walker. The officers are accommodated in deck-houses forward of the saloon. Forward of the main hatch are the galleys. The ship has one of Chaplin’s patent condensers. This is capable of condensing nearly 300 gallons per day. There is also a steam connection with the boiler for heaving up the anchor and cargo, pumping ship, or washing down decks. The condenser, under the management of Mr J. Plackett, has acted well. There is a commodious bathroom, which can be supplied with hot and cold water. The saloon is elegantly decorated with mottoes, which have been prepared for Christmas which have not been removed. They ran “Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year,” “Peace on Earth, Goodwill to all,” “May health and prosperity attend you in New Zealand.” For the convenience of the saloon passengers there was a deck smoking-house on the poop, which must have proved a great comfort to smokers. The voyage appears to have been a very pleasant one, being enlivened by concerts and the publishing of a paper called the Orari Times, which was edited by Mr Burry and illustrated by Lieut. Ludlow.

The Orari was sold out of the company in 1892 to a Mr J.C. Page who reduced her to a barque rig. In 1900 she was acquired by W.W.G. Irvine, but in 1909 she was damaged by an explosion in her hold at Swansea and afterwards she was used as a hulk. She disappeared from Lloyds register in 1911.

The eighteen sailing vessels that were owned the NZSC are as follows:-

| Name | Builder | Year | In service | Tons | Dimensions | Fate | |

| White Eagle/Pareora | A Stephen | Glasgow | 1855 | 1877-1886 | 879 | 199 x 31 x 21 | 1889 – Broken up |

| Waitara | J Reid, | Glasgow | 1863 | 1873-1883 | 833 | 182 x 31 x 21 | 1883 – Lost at sea |

| Rangitiki | M Samuelson | Hull | 1863 | 1873-1899 | 1,188 | 210 x 35 x 23 | 1911 – Hulked |

| City of Perth/Turakina | C Connell | Glasgow | 1868 | 1883-1899 | 1,189 | 232 x 35 x 22 | 1914 – Broken up |

| Waimea | Goddefroy-Zeit | Hamburg | 1868 | 1873-1896 | 848 | 194 x 32 x 19 | 1897 – Wrecked |

| Mataura | Aitken & Mansel | Glasgow | 1868 | 1873-1895 | 853 | 199 x 33 x 20 | 1900 – abandoned at sea |

| Rakaia | J Blumer | Sunderland | 1873 | 1873-1893 | 1,022 | 210 x 34 x 19 | 1920 – Broken up |

| Waikato | J Blumer | Sunderland | 1874 | 1874-1898 | 1,021 | 210 x 34 x 19 | 1913 – Sank |

| Waimate | J Blumer | Sunderland | 1874 | 1874-1895 | 1,124 | 220 x 35 x 21 | 1898 – Lost at sea |

| Waitangi | J Blumer | Sunderland | 1874 | 1874-1899 | 1,128 | 222 x 31 x 21 | 1913 – Lost at sea |

| Hurunui | Palmers | Jarrow | 1875 | 1875-1895 | 1,012 | 204 x 34 x 20 | 1915 – Sunk by U-Boat |

| Orari | Palmers | Jarrow | 1875 | 1875-1892 | 1,011 | 204 x 34 x 20 | 1911 – Deleted from register |

| Otaki | Palmers | Jarrow | 1875 | 1875-1892 | 1,014 | 204 x 34 x 20 | 1895 – Wrecked |

| Waipa | Palmers | Jarrow | 1875 | 1875-1894 | 1,017 | 204 x 34 x 20 | 1911 – Lost at sea |

| Wairoa | A Stephen | Glasgow | 1876 | 1876-1897 | 1,076 | 215 x 34 x 20 | 1919 – Broken up |

| Piako | A Stephen | Glasgow | 1876 | 1876-1892 | 1,075 | 215 x 34 x 20 | 1900 – Lost at sea |

| Wanganui | A Stephen | Glasgow | 1877 | 1877-1888 | 1,077 | 215 x 34 x 20 | 1917 – Sunk by U-Boat |

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item