The Father of Modern Cruise Ship Travel

Just how much influence we have over our own destiny and how much is dictated by circumstance has taxed the minds of philosophers across millennia. In the world of shipping perhaps one man exemplifies how influential each can be on a single life. That man was Albert Ballin.

Ballin was born in his beloved Hamburg on 15th August 1857, the son of Danish-Jewish parents. His father ran the local office of a Liverpool based shipping agent called Morris & Co. arranging passage for (primarily) German, Polish and Russian emigrants onboard American Line steamers between Liverpool and Philadelphia. The Ballin run agency was a small, barely profitable concern and when the father died in 1875 it passed, by tradition, to the eldest of Albert’s six older siblings.

The new owner was even less successful than his father and as the business lurched towards bankruptcy he passed it to the youngest member of the family, seventeen year old Albert. The short, shy, doughy faced teenager, referred to by a contemporary as ’somewhat less than handsome’, was an improbable shipping tycoon. At school he excelled at music and remained a keen cellist for the rest of his life, but otherwise displayed few of the attributes required of a successful businessman. Nevertheless with enthusiasm and a keen eye for detail young Albert developed the agency and increased both revenue and profits. It was his good fortune to take over the reins just as Hamburg was entering its heyday as the largest transit port for westbound emigrants heading for the USA. Indeed the numbers passing through the great Hanseatic port increased fivefold in the five years after Albert took over.

Despite the new found prosperity Ballin resented sharing his commission with the Liverpool based parent company and considered he could increase both income and influence working directly with a local operator. Still in his early twenties, Albert scoured the market and ultimately negotiated an agreement with Carr Linie. It speaks volumes for the young entrepreneur’s acumen and persuasiveness that he was able to convince the cargo company’s owner to adapt their two new freighters to take 700 emigrant passengers each. Riding on the crest of the European exodus Carr Line’s ships were booked to capacity. Adapting other vessels, on Albert’s recommendation, resulted in the total number carried by the company quadrupling in two years. This success spiked the interest of the city’s principle emigrant carrier, Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Actien-Gesellschaft, commonly referred to as HAPAG.

In 1886, barely a decade after starting in business Ballin was instrumental in negotiating the merger of Carr Linie into the HAPAG empire, and having impressed the later company’s board the diminutive twenty eight year old became head of the entire North American passenger division. HAPAG was very much the sleeping giant of the transatlantic trade, ranking twenty second in the list of carriers despite its geographical pre-eminence as a conduit for Eastern European and Scandinavian emigrants. Hard working and ambitious, both personally and corporately, Albert Ballin sought to rectify this travesty. It’s difficult to imagine the suspicion and resentment this enthusiastic and progressive thinking young man must have fostered in such a staid and reactionary company. Of course Ballin cared little about such views, believing only that he should be judged on results. Evidently those who mattered on the company board shared their young protégé’s vision.

He focussed on two key elements, challenging Britain’s merchant maritime hegemony and modernising the company’s outdated fleet. Addressing what he perceived to be unfair British competition, Ballin sought to redress the balance of power. One of his first steps was the acquisition of a Baltic based rival Stettiner Lloyd which operated from the eponymous port direct to New York. With additional calls at Scandinavian ports HAPAG now gained a foothold in what had been British and Danish monopoly. Strengthening the company’s position in this market gave Ballin increased leverage in negotiations with his British rivals. In the end he agreed to discontinuing the Scandinavian calls in return for imposing a limit on the number of America bound emigrants passing through Hamburg via British ports. With a one third limit of the exponential growth, HAPAG’s market share rose dramatically.

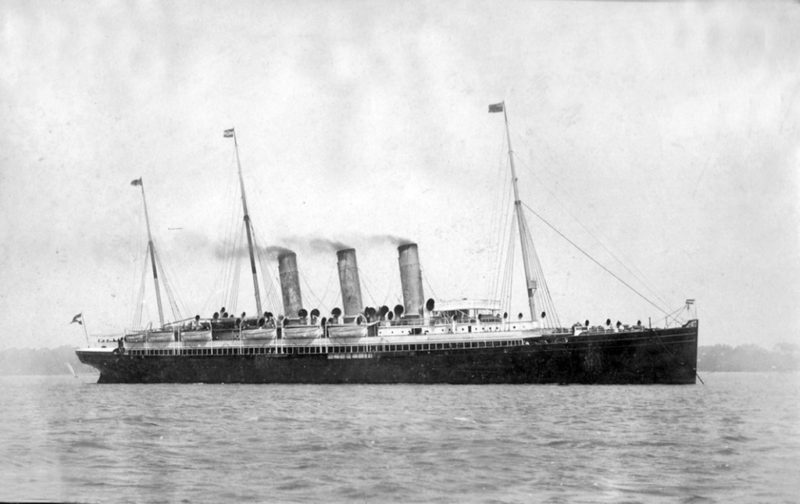

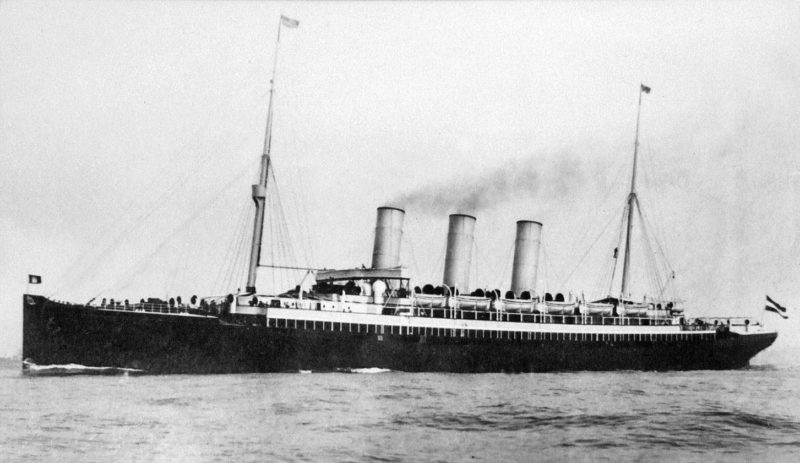

Meeting this increased market share would require new ships and even before he joined the company there had been talk of new vessels, both to compete with the British but also to assuage the board’s envious glances at their Bremen based rivals, Norddeutscher Lloyd. Nevertheless it was at Ballin’s recommendation that on 6th October 1887 HAPAG’s board approved the order for a pair of twin-screw express liners. They would be capable of carrying 1,100 passengers, approximately half in steerage, at a service speed of 18 knots. The first vessel, named Augusta Victoria (erroneously it transpires, the Empress’s actual name was Auguste Victoria and incredibly the liner wouldn’t be correctly renamed for a further eight years) was built by the AG Vulcan shipyard at Stettin. It was a remarkable feat for Germany’s still fledgling shipbuilding industry. At 7,661 grt and 145 metres in length the new liner finally announced HAPAG’s arrival as a major contender on the North Atlantic. A sister, Columbia, arrived two months later from Laird Bros. on the Mersey and this first pair were joined by two slightly larger running mates, Normannia and Furst Bismarck, over the subsequent couple of years.

By the time Augusta Victoria had been delivered in April 1889 Albert Ballin had been appointed to HAPAG’s board of directors. At thirty one years old the ugly, shy cellist was now one of the most influential men in German commerce.

An early example of Ballin’s ingenuity and singular ability came the following year. North European based shipping lines had faced a dilemma since the inception of steamship transatlantic travel, best summed up by a three letter nautical acronym that sent a shiver down the spine of many mariners, WNA (Winter North Atlantic). Whilst summer traffic poured revenue into and garnered profits for the lines, the winter months would frequently drain the company coffers. The most common solution was to lay vessels up over the ‘low’ season, however there were still overheads to cover, including docking fees, and crew would be laid off and then re-hired in the subsequent spring. Ballin’s solution was to send one of the quartet cruising.

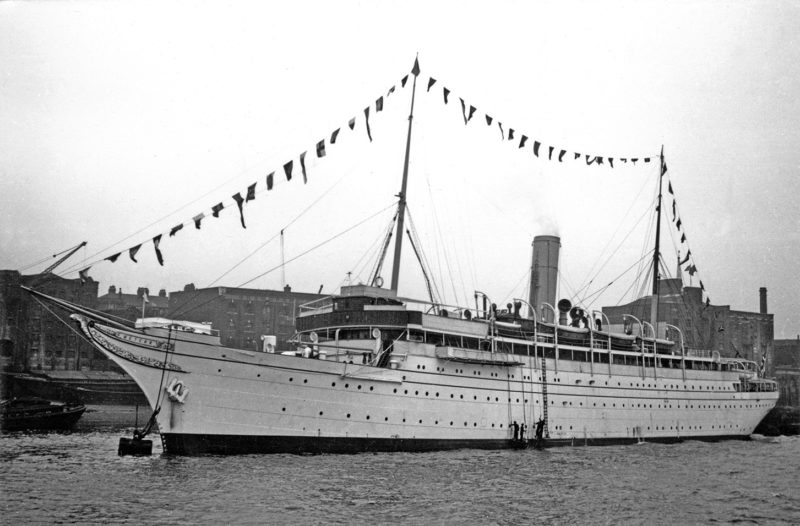

Although P&O had introduced the concept of the pleasure cruise earlier in the century HAPAG would be the first shipping line to utilise one of their main liners for the purpose. On 22nd January 1891 two hundred and forty one passengers boarded Augusta Victoria for the grandiosely titled ’Great Excursion to Italy and the Orient’. Despite Ballin’s usual meticulous planning (he had researched the itinerary for almost a year and enlisted the help of Thomas Cook and Son when devising shore excursions) the concept was certainly a gamble. When she departed Cuxhaven that cold winter day Augusta Victoria was sailing into the unknown, but as so often with Albert Ballin it proved to be a calculated risk that paid off. Not only was the cruise fully booked but it garnered rave reviews from passengers and press alike. Plans immediately started for a repeat the following year.

Like a modern Midas it appeared everything Ballin touched became a success, and as HAPAG’s status and prominence grew, so metaphorically did the little man’s social and political stature. The Augusta Victoria’s maiden cruise departure was significant not only in the context of the voyage itself but in introducing him to Kaiser Wilhelm II. The German emperor was a keen naval advocate and Ballin’s personal guided tour of the ship fostered an enduring but ultimately controversial friendship. Lead by this confident, articulate and witty conversationalist, the Ballin household consisting of Albert, his wife and adopted daughter, became a focal point of German society, entertaining the wealthy and influential from all walks of life. His grand villa in the Rotherbaum district of Hamburg included, in due course a suite of rooms for the Kaiser’s use when he was in the city. It was an impressive building.

Albert Ballin was a staunch patriot and his forthright views on increasing Germany’s international standing are often construed as warmongering, especially in light of subsequent events. Like his friend, the Kaiser, he wanted Germany to achieve maritime parity with Britain whose fleets bestrode the globe. However for Ballin this was a benign exercise in commercial and not military competitiveness. He was a confirmed anglophile and fluent English speaker, with numerous friendships dating back to his time working for Morris & Co. as a naïve but enthusiastic teenager.

The HAPAG fleet continued to grow under his stewardship throughout the following decade. The earlier quartet were supplemented by a total of ten ‘P’ class cargo liners. The first pair, called Prussia and Persia, were 5,796 grt ships designed in conjunction with Harland & Wolff at Belfast and offering accommodation for sixty First Class passengers and one thousand eight hundred emigrants. With 7,500 tons of cargo capacity and a modest, economical twelve knot service speed the ships were hardly extravagant but proved so successful and profitable, even in the uncertain economic climate, that a further batch of five, slightly larger sisters were introduced. Yet more new tonnage followed, ‘A’ and ‘B’ class vessels, with names to match, were steaming out of British and German yards throughout the 1890s populating the shipping lanes to South America, the Far East and the Mediterranean as well as the North Atlantic. Given this expansion to new destinations it is perhaps ironic that in 1893 the company decided to abbreviate it’s formal title to Hamburg-Amerika Linie. The decision materially changed nothing and it would continue to be referred to by the acronym HAPAG. By the mid-1890s Albert Ballin’s position as the most influential decision maker on the HAPAG board seemed assured and he alone would dictate the direction of the company. However a single, four funnelled rival, would challenge that assertion.

In 1897 Norddeutscher Lloyd introduced Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, the largest, most luxurious and, crucially, fastest passenger ship in the world. The new ship’s genesis could be traced to Kaiser Wilhelm II’s attendance at the Spithead Naval review of August 1889. Here he had visited the White Star Line’s Teutonic, then the largest liner in service. The young Emperor was deeply impressed by his grandmother, Queen Victoria’s show of naval strength and resolved to match the military and merchant might of Britain on the seas. Eight years later ‘rolling Billy’, as the new ship was known on account of her tendency to roll alarmingly in even moderate seas, arrived and fulfilled a nation’s ambition. There was consternation in Hamburg.

When the HAPAG board met an impassioned discussion ensued. Not only had their Bremen rivals stolen a march by becoming the first German holders of the coveted Blue Riband of the Atlantic, they had achieved this by contracting the Vulkan shipyard. Ballin’s innate business acumen warned against competing with the new ship’s size and speed. He was convinced that the ruinously high construction and operational costs for such a vessel were unjustifiable. It was a view dating back to his experience with Carr Linie whereby spacious well-appointed but slower ships proved just as popular and eminently more economical than their faster rivals. He knew the pursuit of record breaking speed was a costly, transient goal, at best providing a brief moment in the limelight that would soon be eclipsed. Despite his vehement objection Ballin’s reasoned arguments fell on deaf ears, he was outvoted as the HAPAG board approved the order for a slightly larger and faster facsimile of the NDL champion.

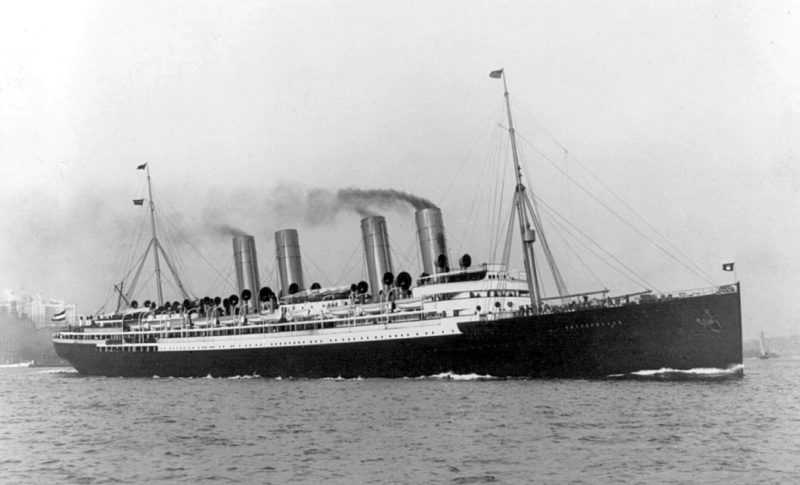

As usual Ballin’s view proved prophetic. HAPAG got their Blue Riband, but the four funnelled, 16,502 grt Deutschland proved to be the company’s most ill-judged investment. A voracious appetite for coal was predictable but her unflattering nickname of ‘The Cocktail Shaker’ belied chronic vibration problems that plagued her throughout her career. As a one-off with a service speed almost four knots higher than her fleetmates, Deutschland was always going to be the cuckoo in the HAPAG nest. Nevertheless she achieved the board’s goal and ensured the company was written into the record books. By the time the new flagship entered service in July 1900 Albert Ballin had been appointed managing director.

The new century heralded both consolidation and further expansion of the Hamburg-Amerika Linie under the direct control of their new MD. Despite its growth into the largest shipping company in the world, the company’s concentration on medium sized, economic vessels, reflecting Albert Ballin’s preference, left the express transatlantic service languishing far behind its competitors. He had proven the dubious value of speed with Deutschland and instead recommended that any new orders reflect Britain’s White Star Line’s philosophy, concentrating on size and comfort. Unsurprisingly given his customary pragmatism Ballin approached Harland & Wolff which had helped on the development of the ‘P’ class steamers and recently delivered White Star’s Celtic and Cedric to design and build the first of HAPAG’s new liners.

The German ships would be slightly larger and faster than their British near sisters but it was in their accommodation and appointments that they sought to outdo their rivals. Ballin’s perfectionism was legendary, his ever present notebook feared by officers, crew and management alike as he jotted down perceived flaws in service, fixtures and fittings. If some of the ensuing directives appear over zealous (the butter dishes need to be larger, pillows more plump, playing cards should be embossed with the company logo, etc etc), it was these exacting standards that had allowed HAPAG to achieve it’s potential. He travelled extensively, always where possible onboard the company’s fleet, testing and assessing, and canvassing the opinion of fellow passengers. On one trip to London the pencil and pad were in constant action as Albert Ballin stayed at the Carlton Hotel owned by César Ritz, whose eponymous Parisian hotel had opened in 1898. The quality of service and cuisine, under the vigilant attention of Auguste Escoffier, greatly impressed Ballin, but it was the décor that garlnered his greatest praise. He resolved to find the man responsible and commission him for the new ships. In Charles Mewes, César Ritz and Auguste Escoffier, Albert Ballin met kindred spirits. Ballin’s idea was not only to replicate the style of interiors that adorned the hotels, for which Mewes was employed, but also provide a dining experience to match what he had enjoyed in London.

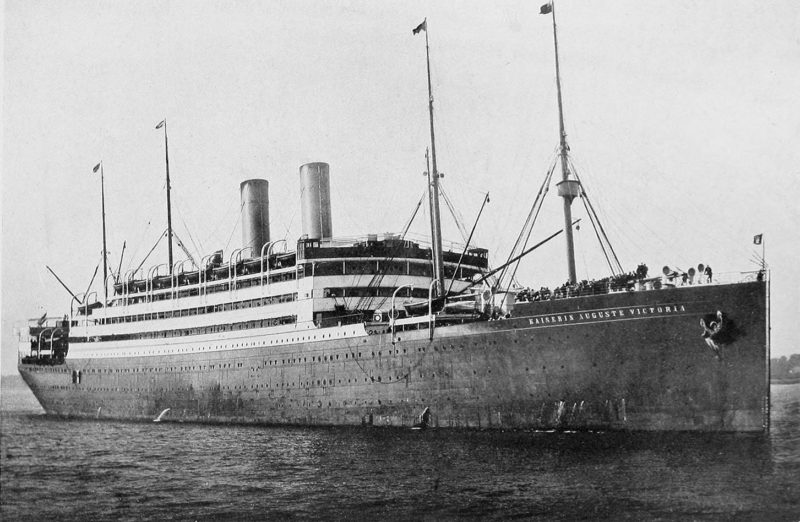

Ballin’s eye for detail and ingenuity were not restricted to First Class. He had long championed an improvement in conditions for emigrants travelling in steerage, even if his motives were not purely altruistic. Those who failed the United States’ draconian health examinations at Ellis Island were forbidden entry to ‘the land of opportunity’ and repatriated at the shipping company’s expense. Furthermore, whilst most emigrants would only make a single voyage west they would invariably be writing to those they had left behind about the experience, some of whom would follow. The power of recommendation was arguably more important in Third Class than in the lavish world of First, for that was where the greatest profits lay. So the new ships would feature more spacious and clean accommodation in steerage, whilst for a moderate premium Third Class passengers would utilise two to six berth cabins and eat food cooked in the adjacent kitchens in a designated dining room, with attendant stewards. These were significant innovations, indicative of Ballin’s humanity as much as his business acumen and prompted other lines to rethink how they treated their largest but least vocal clientele. When Amerika entered service on 11th October 1905 she secured HAPAG’s place amongst the elite transatlantic carriers. Escoffier’s chefs ensured that the same quality of culinary experience was available in mid-Atlantic as would be available in London or Paris. Ballin even persuaded Nagel, maitre d’hôtel of the London Ritz-Carlton grill, to supervise the whole operation in that maiden year, developing a reputation for quality that endured over the ensuing decade. Following earlier precedent the second ship was to be built in Germany. Commissioned from the same Stettin Vulkan yard that had built Deutschland, although she differed from her Belfast built sister by having an additional deck. Nominally referred to by her originally assigned name of Europa, at 24,581 grt she entered service as Kaiserin Auguste Victoria, named after her godmother, the largest ship afloat. Doubtless the Kaiser was pleased.

With further reference to steerage conditions Ballin’s attention was no longer limited to ships. In his usual perceptive manner he began to address wider social issues that impacted on the business. As the volume of emigrants increased so did extortion in his native Hamburg. Exhausted travellers, often with little or no knowledge of German were easy prey for unscrupulous or even bogus officials and pedlars, who would charge exorbitant fees for shoddy lodgings and food. Ballin resolved to address the problem by building his own Emigrant Village and in 1901 promptly acquired a fifteen acre stretch of Elbe waterfront on the Island of Veddel. Over the next five years the company developed the site, constructing a series of buildings to house, feed and entertain those in transit. New arrivals, who had often arrived by train on a combined ticket basis, were initially accommodated on the landward ‘unclean’ side of the complex. Here they were showered and given a medical examination whilst their belongings were thoroughly fumigated before passing through to the seaward ‘clean’ buildings. Safely housed for a reasonable fee, the emigrants were provided with a canteen offering cheap, wholesome food, a church and even a hospital, whilst they awaited their westward voyage.

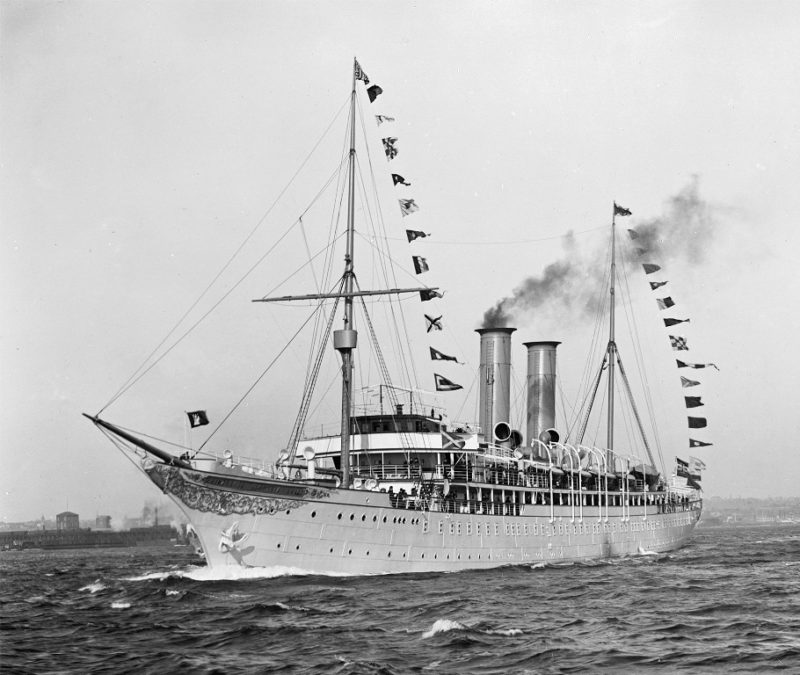

Meanwhile, in complete contrast, Ballin persuaded his fellow board members to approve plans for a revolutionary new ship. The rationale, feeding off the seasonal cruising success of Augusta Victoria and her sisters, whilst addressing the self-evident shortcomings of using express liners for such a role (redundancy of both accommodation and power) resulted in HAPAG placing an order with Blohm & Voss for an all First Class 4,419 grt vessel, designed exclusively for all year cruising. Externally her yacht like appearance included a tropical white hull featuring an ornate clipper bow, two elegant masts and a pair of slender buff-coloured funnels. Internally the décor was luxurious without being ostentatious, providing accommodation for just 198 pampered guests with a range of facilities including a library, gymnasium and even a dark room. Indicative of his hoffähig status at the very summit of German society, Ballin arranged for the new ship to be called Prinzessin Victoria Luise after the Kaiser’s daughter. The worlds first bespoke commercial cruise ship was an instant success when she entered service in 1901 and settled into a seasonal cycle that still prevails more than a century later. Summer was spent predominantly in the Baltic and up the Norwegian coastal fjords, spring and autumn she sailed in the Mediterranean and Black Sea, with long Caribbean voyages in the depths of winter.

Seeking to capitalise on the Prinzessin Victoria Luise’s success Hamburg-Amerika commissioned a second cruise ship three years later. Although smaller and sporting just a single buff funnel Meteor’s passenger capacity was higher at 283 and possibly due to this lack of exclusivity she never quite achieved the popularity and success of her predecessor. Nevertheless her commissioning was indeed timely, within two years Prinzessin Victoria Luise was lost in the most dramatic and tragic of circumstances. On 16th December 1906, whilst under the command of Kapitan Brunswig, who had eschewed the local pilot, the cruise ship ran aground in Kingston Harbour, Jamaica. Despite a desperate attempt by the German cruiser Bremen to tow her free the beautiful ship foundered. Devastated by his error Kapitan Brunswig retired to his cabin and took his own life.

As we have already witnessed Albert Ballin was a shrewd and successful businessman. Detractors have criticised his propensity to acquire (devour?!) less profitable lines, either in a bid to crush opposition or to establish new routes. The evidence suggests that far from being exploitive Ballin not only provided acquired line’s shareholders with generous deals but invariably secured employment for their ships and crews. Furthermore HAPAG staff and their relatives benefitted from a broad range of financial and welfare schemes, long before central government provided a similar safety net. It is clear that Ballin valued his workforce and clientele, whether this was driven by business or philanthropic motives is largely irrelevant. Where he led others would ultimately follow.

Arguably his greatest achievement was not in acquiring another shipping company but in resisting a takeover. Hamburg Amerika Line had become a target for J. Piermont Morgan’s International Mercantile Marine (IMM). The American shipping conglomerate had already swallowed up Red Star Line, White Star Line and any number of smaller operators. Now Morgan set his sights on the largest of all, Hamburg Amerika Line, Ballin the hunter was now the prey. Unlike Cunard which had run to the British Government for financial support to avoid an unwanted approach, Ballin took a very different strategy. Rather than capitulate or confront the Americans, Ballin negotiated a mutually beneficial arrangement. Superficially it looked lop-sided. Furthermore, aware that Norddeutscher Lloyd was also threatened, Ballin showed his wider support for German business by including them in the agreement.

Under the terms of the deal HAPAG and NDL would pay the IMM a quarter of any shareholders’ dividend exceeding six per cent. Conversely the IMM would have to pay the German lines a quarter of any dividend that fell below six per cent. If it seemed that the Americans were receiving money for nothing Ballin’s ploy would successfully ensure that the IMM had a vested interest in maximising HAPAG’s and NDL’s profits.

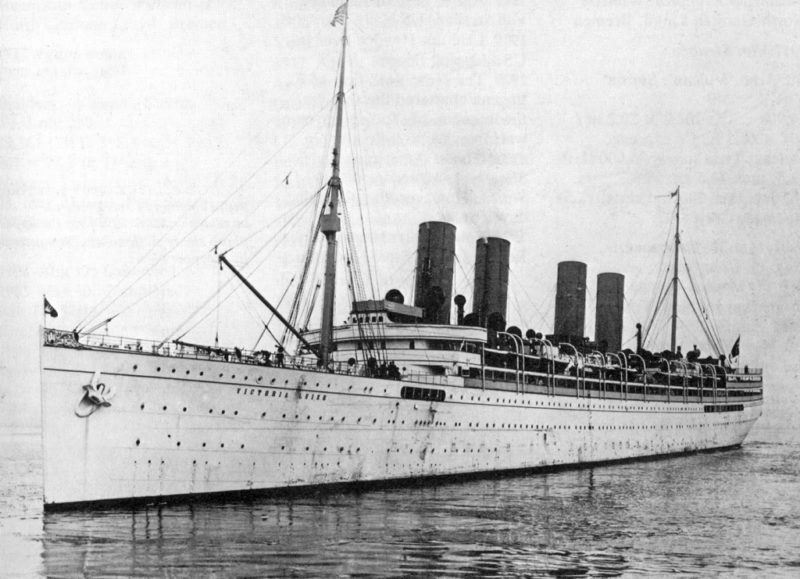

As previously alluded to, the record breaking, crockery smashing Deutschland had never quite fitted into the company’s transatlantic schedules. With her high fuel consumption and running costs, not to mention the chronic vibration, she was amongst the least profitable vessels in the fleet. As Ballin had predicted the Blue Riband proved only fleetingly beneficial, even if, with a brief hiatus when NDL’s Kronprinz Wilhelm held the honour, she clung to the coveted title for seven years. Addressing the fact that HAPAG had never quite regained the cruising excellence of Prinzessin Victoria Luise (her replacement Oceana, the former Union liner Scot, had been unable to rekindle the earlier ship’s success) Ballin hit on a daring solution. He decided to take Deutschland out of service and send her for a ten month transformation into the largest cruise ship afloat. When she finally emerged from the Vulkan yard her name had been shrewdly changed to Victoria Luise, evoking memories of the earlier, highly popular vessel lost at Kingston. Externally the white hull immediately hinted at the former speed queen’s new role, even if it proved almost impossible to maintain in pristine condition and within months reverted to the original black. Internally the public rooms were reconfigured to offer spacious and luxurious accommodation for just 487 cruise-goers, less than half her original complement. The key to profitable service was the reduction in engine power resulting from the removal of the aft boiler room and adjacent machinery. The resulting void was filled by a new indoor swimming pool. Although the aft pair of funnels were now redundant they were initially retained to keep a balanced profile. By the time Victoria Luise sailed from New York on her first cruise to the West Indies in February 1912 Albert Ballin had moved on to his defining, but sadly unfulfilled project.

Citing Amerika and Kaiserin Auguste Victoria’s success Ballin propositioned the board with his most ambitious plan yet. HAPAG, he mused, should cement its position as the worlds largest and most prestigious shipping line by introducing the largest and most luxurious trio of vessels ever conceived. The intention was to provide a weekly service between Europe and America in direct competition with White Star’s Olympic class and Cunard’s Mauretania, Lusitania and newbuild Aquitania. Fleeting speed records he intended to leave to Cunard, although incorporating steam turbine machinery for the first time on HAPAG liners the new vessels would be no slouches with their 23 knot service speed. The first ship was named Imperator by Kaiser Wihelm II, accompanied on the lofty, precarious platform by his close friend Albert Ballin, on 23rd May 1912. Rich in Imperial pomp the ceremony emphasised Germany’s growing naval ambition and has been seen as a portent of impending military confrontation. However ship’s launchings, especially the largest in the world, have always been choreographed as a display of national pride, ambition and might. Imperator was no exception.

In April 1913 Imperator left her Hamburg builders and set forth into the North Sea for trials. Various modifications, including the addition of an inner double bottom and a small fleet of lifeboats, had been incorporated in light of the Titanic tragedy but as she headed for the open sea a further serious flaw revealed itself, HAPAG’s new flagship was top heavy and her stability compromised. Despite this concern, when she cast off from Cuxhaven on 10th June 1913 for her delayed maiden voyage, the scale of her public rooms coupled with the sumptuousness of Mewes’ interiors were widely acclaimed. Chastised by New York stevedores as the ‘Limperator’ the new ship proved as popular as she was unsteady. Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the new ship was her oversized, eagle figurehead. There have been various theories proposed as to why the huge bird, grasping a globe in its talons with the HAPAG motto ‘Mein Feld ist die Welt’'(My field is the world), was installed, but within a few months they became irrelevant. The North Atlantic, that great leveller of man’s vanity, simply ripped the splayed wings from the birds bronze torso in a gale. Realising its impracticality (the wings had also hampered mooring parties), the body, head with imperial crown and motifed sphere pedestal were quietly removed on her subsequent Cuxhaven turnaround. As for the stability problems, she would remain a ‘tender’ ship but the balance was partially restored by replacing the heavy marble fittings in her upper deck First Class staterooms with lighter substitutes, exchanging heavy furniture with cane and ratten alternatives and most vividly trimming 30 feet off her three enormous stacks.

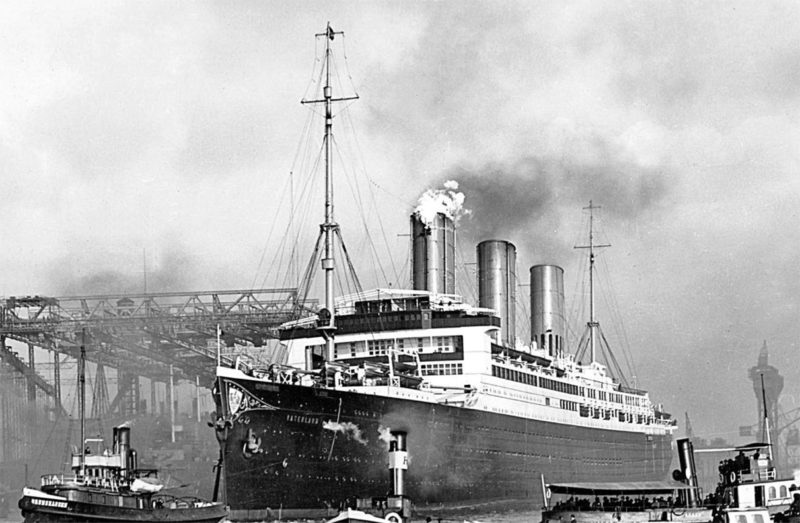

In another overtly nationalistic gesture the second of Ballin’s trio was launched as Vaterland in April 1913. At 54,282grt she was larger than her older sister and according to contemporaries possessed a presence that dominated all around her. Indeed like a latter day Gulliver she proved almost too large and extreme for the Lilliputian world she inhabited. Twenty five tugs were deployed to usher the new behemoth into her Hoboken slip at the end of her maiden voyage on 22nd May 1914. During the subsequent return departure a problem with one of the astern turbines almost caused her to career into facilities on the opposite Manhatten bank of the Hudson. In averting disaster the great ship’s wash swamped and sank a pair of coal barges, killing one crewman and buckling pier stanchions with the detritus left in her wake.

The third and final vessel of the three ship service was launched the following month. Alas Bismarck would never see service for Hamburg America Line. In those final months of peace, perhaps sensing the impending asinine descent into conflict Albert Ballin’s health started to deteriorate. Always a fidgety workaholic he developed chronic insomnia. Depression took hold and those attending the famous banquets at his Hamburg villa witnessed his previous spirited vivacity replaced by melancholy and temperamental outbursts. ‘Life is just one damn thing after another’ read the new motto on his desk, as he saw key players on all sides ramping up the rhetoric and lurching towards war. Attempting to use what influence he had and his renowned negotiating skills, Ballin undertook a desperate round of shuttle diplomacy between London and Berlin. He pleaded with the naval commander Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, by all means let Britain and Germany compete for maritime supremacy but let it be between Aquitania and Vaterland rather than dreadnoughts.

Those who criticise Ballin’s closeness to the ruling elite and categorise him as a fellow warmonger fail to account for a fundamental truth. He and HAPAG were tantalisingly close to realising their ultimate goal of a three ship transatlantic service that would eclipse the opposition. Quite simply he and his company had the most to lose from the ensuing Great War that destroyed so many plans and ambitions, along with millions of lives. Ballin witnessed the steady dismemberment of his fleet as it was commandeered or confiscated by foreign powers. Imperator sat the war out in Hamburg, Vaterland remained laid up at her Hoboken pier in the neutral USA until April 1917, when the Americans declared war on Germany. Transformed into the troopship Leviathan she then shuttled doughboys across the Atlantic to fight her native land. Bismarck remained incomplete, materials were needed for the war effort and when finally she was finished it was as White Star Line’s Majestic that she made her maiden crossing. Disillusioned and dispirited Ballin nevertheless devoted himself to lobbying for HAPAG crew members rights. He secured a compensation agreement with the Government for lost tonnage, which covered all requisitioned commercial vessels irrespective of owner, turned the Emigrant Village into a hospital and set up a company to supply food to the city. In the summer of 1918 he once again pleaded with his friend, the Kaiser, to sue for peace and end the pointless bloodshed. As the war finally approached it’s conclusion Ballin got caught up in the November Revolution that swept northern Germany.

On the 8th November 1918 his offices were commandeered by revolutionaries. Humiliated, Albert packed away his personal possessions and went home. Realising perhaps the hopelessness of his situation and the retribution he and his family might suffer through their association with the Imperial court Ballin took a dose of sedatives. Whether he intended to take his own life or the sedatives reacted with his numerous other prescribed medicines was never firmly established. He was taken to hospital but died the following day. Albert Ballin was just one of the innocent casualties of that tragedy of humanity but his legacy lived on, both in the improved treatment of emigrants and the ultimate spawning of the modern cruise industry.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item