by Norman Rawlinson

Some Memories Of Two Ships – Irisbank And Maplebank

A Bank Line ship appointment in the 1950s offered a rare chance to sail the world, visiting almost every corner, and spending time in a a host of ports, including many out of the way places. At the time, there was a different perception. Unless you were lucky, or well connected and sent to a new building vessel, the chances were that the first sighting of a Bank Line ship would evoke mixed feelings. The hull might be rusty or have rust streaks, the gangway look a bit rickety, and there may well have been a rich pungent smell from the discharging cargo, usually copra and coconut oil, but let it be known that what awaited you was pure unadulterated magic!

Again, the perception has changed with the passing of the years. This was an iconic British shipping company, unlike any other. Similar to many, but head and shoulders above the pack. The owner, Andrew Weir, later Lord Inverforth, had steadily built his empire, and he was still attending the office in his 90th year. The ships were maintained in workmanlike style, not lavish by any means, but certainly not neglected in any way.

The voyages were for two years maximum, and so it often proved. Some vessels which were suited to load oil in deep tanks, were particularly handy for the Pacific islands, slowly trawling around the beguiling island groups, and they could be back home in around six months. They were called ‘Copra ships’, in the company, and a berth was highly prized for obvious reasons. A fleet of around 50 Bank Line ships circled the globe constantly and although tramping played a part, the majority of the cargoes and routings were the result of long established trades served, not by the same vessels, but by a procession of newly arriving vessels on their way around the world. The various fixed contracts were augmented by spot chartering, and it was this lottery of destinations that introduced the random trips and made life on board so fascinating. The network of agents and offices had been steadily built up from early beginnings with a similar sized sailing fleet which included the famous Olivebank. These worldwide connections were somewhat unique, and much more substantial than we realised on board, naturally only concerned with the next port.

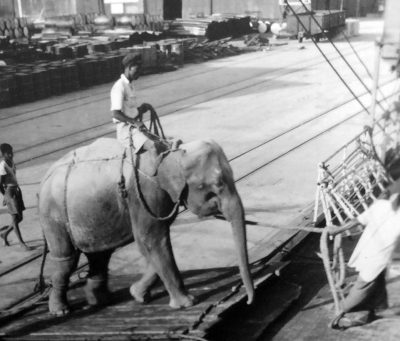

Once up on deck, especially in the middle of discharging and with necessary repairs going on, it looked chaotic. These ships had Indian crews in the main, and the man guarding the gangway, called a Seacunny, would likely assist with all your bags and trunks. Many of the apprentices and officers travelled with an exorbitant amount of baggage, laughably regarded as essential for two years on board. The old ships had wooden hatch boards, and steel beams, and at sea the hatches were covered with two or more heavy tarpaulins. In port, these items helped litter the decks turning it into an obstacle course, and the clutter was made worse by hoses, pipes and cables if repairs were underway. And of course, discharging continued with grabs flying in and out of the holds.

Even on the older pre war vessels, the Master and Chief Engineer would have quite roomy accommodation, but for the rest of us, the two years would be spent in a small white painted cabin, sometimes with tongue and groove panelled bulkheads. The bunks were narrow, and blue quilts with the Bank Line motive would be tightly stretched over them. A writing bureau and a narrow settee would complete the furnishings, and depending on the age of the vessel there may have been a wash basin, but definitely no running water. A brass port provided light and air, but sometimes a metal scoop was all that was available to relieve the humidity in the tropics. Oscillating fans were highly prized in the mid 50s! The pre war buildings often had a weird wooden contraption for washing, with a tip up basin, allowing any water to slosh down to a tank in the bottom for manual emptying.

On the 1930 built Irisbank, in which the author spent 2 years, the bathroom, shared by the officers and apprentices was a functional part of our life, and we quickly adapted to the primitive conditions. No fresh water was available, unless hand carried in from the pumps on or below decks, but salt water was laid on. A bath, normal looking, had a steam pipe attached, the idea being that water, either salt or fresh, laboriously carried in, would be rapidly heated. The copper steam pipe was swivelled, and the business end was swung around and poked under the water before the valve was opened. It made a very loud raucous noise not unlike a tube train approaching. Adjacent to the sink was a handy electric copper tank which heated fresh water for hand washing etc. It came in useful in very bad weather, at times when the galley gave up the struggle, when bizarrely, the author boiled eggs hung in the toe of a sock trapped under the lid!

Food in the Bank Line was usually satisfactory without any frills. The saloon table would be attractively laid out, with often the menu stuck in the prongs of a fork! Curry and rice featured strongly, and appeared occasionally on the breakfast menu. The curry concoctions were a work of art, the author’s favourite being one with a sea of shimmering oil with halves of hard boiled eggs floating free. The colour of the surface changed into different hues as it moved. The apprentices were always hungry, but in extremis it was possible to cadge a chapati from the Indian cooks or Bhandaries, who catered for the deck and engine room crew. On the older Bank Line ships, a distinctive feature was steel accommodation blocks either abeam of the foremast or mainmast and on either side. These housed the crew galley, and also toilet blocks. Arriving in a port anywhere in the world, day or night, it was often possible to pick out the outline of one of the old Bank Line stalwarts – true work horses of the oceans they were. Apart from the distinctive blocks on deck, the derricks were usually lattice type, a box with criss cross strengthening on all four sides, and the steam winches would all be clattering away as the cargo was furiously loaded or discharged, a string of barges alongside. Decks were sheathed in pine, and scrubbed up or holystoned after a long port stay, they turned near white and glistened in the wet. Open rails instead of today’s bulwarks complete the picture.

Life on board usually settled into a steady routine, quite sedate at sea, but enlivened dramatically in port. Some of the more exotic locations promised an interesting if not riotous time, and part of the attraction of this type of seafaring was exactly that. Buenos Aires and all of the ports around the South American coast, East and West, could be relied upon for an interesting time, inevitably involving the local brew, the girls, and local cuisine, notably the steaks. And in no particular order. Before Juan Peron was ousted in Argentina the atmosphere was somehow heightened, and in Buenos Aires there was a notorious area in the docks called ‘The Arches’, which were railway arches utilised for bars, restaurants and worse. It was a rough area, and attracted us all like a magnet.

The usual Bank Line voyages in the 1950s started with a light ship voyage out to the U.S. Gulf, but sometimes Trinidad for bitumen. These cargoes all went down to Australia or New Zealand.

In the Gulf there were a range of loading ports starting with Brownsville close to the Mexican border, and all along the coast to the Mississippi Delta which served both New Orleans and Baton Rouge much further up. Loading took place in a mix of these fascinating ports, with their distinctive smell of oil, gas, and chemicals. Lubricating oil went into the deep tanks, and a base cargo of rock sulphur or sometimes potash went into the lower holds. This was quickly levelled and boarded over for a cargo of farm machinery, largely tractors, but often other large mysterious objects, all secured with rolls of shiny new wire. It wasn’t unusual for them to break free in heavy weather, however. The ‘tweendecks then received a wide mix of general cargo, almost always including pallets of carbon black, and stacks of Hickory handles. More machinery would be lashed onto the hatch tops. Containers were yet to come, but the level of interest and variety of cargo was hard to beat back then in the 1950s.

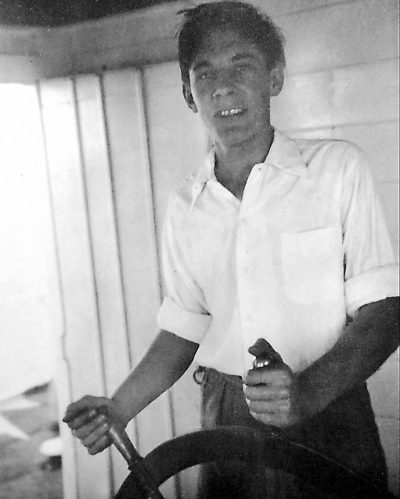

Watches on the bridge followed a strict routine, and this was long before satellite and global positioning spoiled the fun of position finding. The actual wheelhouse on the old timers was quite often small but somehow homily, if that is possible. Before automatic steering, a quartermaster stood silently behind the wheel, and he was watching a magnetic compass in the binnacle, steering a course marked up on a chalk board by the officer of the watch. There would be a manual voice pipe to the Master’s cabin, a brass telegraph, and a small side table with a dim or coloured bulb. During this period, the first radar sets were being fitted and space was found for the display unit on a low table. Early models were unreliable and became the bane of Sparkie’s lives as they were hauled out regularly to fix breakdowns. Many Masters ordered their use very reluctantly, or reserved the time they were switched on to pilotage areas, or passing the many islands in the Pacific and elsewhere. The doors either side of the wheelhouse led out to a short bridge wing with ‘cabs’ for weather protection at the ship’s side. These heavy doors slid open and shut and were held in place with wooden wedges. The bridge front had drop down wooden dodgers in the traditional manner, but one or two shorter Masters were known to use a box to see forward.

Above the wheelhouse, the so called ‘monkey island’ was accessed by short vertical ladders, and on a raised platform would be the standard compass with an azimuth ring on top, and protected by a binnacle hood. In those far off days, this compass was a crucial part of the navigation, and was in constant use for bearings, both of heavenly bodies, and for coastal bearings as the ship progressed. This exposed area was also a haven of peace and quiet, and could be a magical place at night with a huge canopy of stars and planets, especially in mid Pacific in clear weather when the sight was often breathtaking.

Bank Line ships carried a huge range of charts as standard, running into thousands. These were stowed below the chartroom table behind the wheelhouse, and corrections were a nightmare. Because of the range of charts, it was standard practice to pull out and correct only those charts needed for the immediate voyage ahead. Correction of existing Admiralty charts, and supplementary charts could be obtained in major ports like Sydney or London, but more often than not, the second mate, whose responsibility it was, would have to somehow prepare the courses, and ensure the charts were up to date. The ship regularly received the well known ‘Notices to Mariners’ for this purpose. On the bulkhead would be an impressive array of Admiralty sailing directions in a rack or two. Inside these volumes was a cornucopia of fascinating information, some of it handed down and still printed from Captain Cook’s time. Many a boring watch was saved by delving into these books which seemed to be a mixture of old and new, probably stemming from the fact that there is a long British maritime history garnered worldwide, and alterations and additions seemed to be added ad hoc. In the chartroom would be a settee, often with boxed sextants resting on it, and the standard chart table with a shaded lamp.

The Irisbank, as with other vessels of her generation, sported a ‘modern’ echo sounder. It was positioned on the chartroom bulkhead adjacent to a mercurial barometer. It worked on a pulse from a plate in the keel when switched on, and readings were recorded on a roll of special paper by a rotating stylus. The dampness of the paper was crucial and worked best with a new roll fresh from a sealed pack. The liquid gave off a pungent smell. If the paper dried, which all too frequently happened, the markings faded to nothing, making it difficult to read. Despite the shortcomings it was a huge bonus in 1950s navigation.

This gadget had replaced a manual system in use not many years before, called the Kelvin deep sea sounding machine. The author only used the wire manual machine a few times, and the drill was to swing out a boom maintained for this purpose, and then lower a thin wire to the bottom to record the depth. This was done by means of a dial fixed on the frame. The lead at the end had tallow applied in a recess to determine the bottom composition, in the time honoured fashion. It was cumbersome and tricky and could only be used when near stopped in the water. Plus, the wire had to be oiled as it was retrieved!

In the fleet in the 1950s were a number of Liberty Ships, and these were a quite different experience to sail on. The ports and the random voyages stayed the same, but the accommodation layout and facilities, much improved on regular old time Bank Boats, meant that the company chose to crew them with Europeans. One such was the S.S. Maplebank, ex Samwash, and she was a lovely lady. A bit bedraggled, and maybe a bit over-worked, but a lady none the less. To start with, the American build gave the Liberty ships superior fittings, wider bunks with proper bunk boards instead of slats, running hot and cold water in each cabin, and a heating system to die for. This particular ship had been present at the war landings in Sicily some 10 years earlier. Serving as a senior apprentice, the author looks back with fond memories at the near two year voyage which circled the globe, plus a bit.

The familiar design of the ‘Sam boats’ as they were known included gun bays on the fore side of the bridge structure, and although the guns were long gone, they served as handy lookout positions. In Cook Strait, New Zealand, and heading into a fierce gale, they vibrated alarmingly as the wind was trapped beneath the protruding bays. Another feature and hall mark of the solid looking Liberty ships was the topgallant mast on the mainmast. This gave a very distinctive profile, and was used for signals.

On the bridge, most of the fittings were somehow clunkier than usual, and down below a big simple 3 cylinder steam engine drove her along at the best part of 11 knots. The engine was a classic and the analogy to a Big Tonka toy was hard to deny.

In the Bank Line Liberty ships, the white crew arrangements posed a constant problem. Drink was the cause, because in other respects they were very capable seamen who could rise to any challenge thrown up by the voyage. The Maplebank crew, who were from Liverpool, took to sewing their own work clothes from bolts of duck canvas. Jacket, trousers, and cap were all produced. Their humour was second to none, but it wore a bit thin when they were laid up drunk, and the apprentices, and sometimes the deck officers, were forced to prepare the ship for sea, covering hatches, lowering derricks, and then steering for enough time to let them sober up. On this particular voyage which was typical, the majority deserted in Australia and New Zealand, finding jobs ashore as taxi drivers or on building sites. Some chose bar work which was a natural role given their love of drink.

During our stay on the Australian coast, we drew the short straw on destinations and were nominated for the phosphate run. This meant sailing up and down monotonously from Ocean Island and Nauru with phosphate rock. It went to Australia and New Zealand as land fertiliser, and unlucky was the ship that got ear marked for this interminable run. It took us through the notorious Tasman sea in all weathers. So routine was this run that our crew members decided to lighten the mood by stowing away girls, and a male partner in one case, in their accommodation. This worked successfully for a trip, but then the discharge port on a subsequent voyage was switched to New Zealand, and all hell broke loose when the ‘passengers’ were discovered.

Eventually we moved on in our round the world trek, and after a riotous stay in Buenos Aires we loaded iron ore in Brazil for Bremen, and a ferry trip home. Only one member of the original deck crew was still with us. It had been a memorable voyage, and to coin a phrase, full of tears and laughter!

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item