Memories of the MV Inchanga in 1952

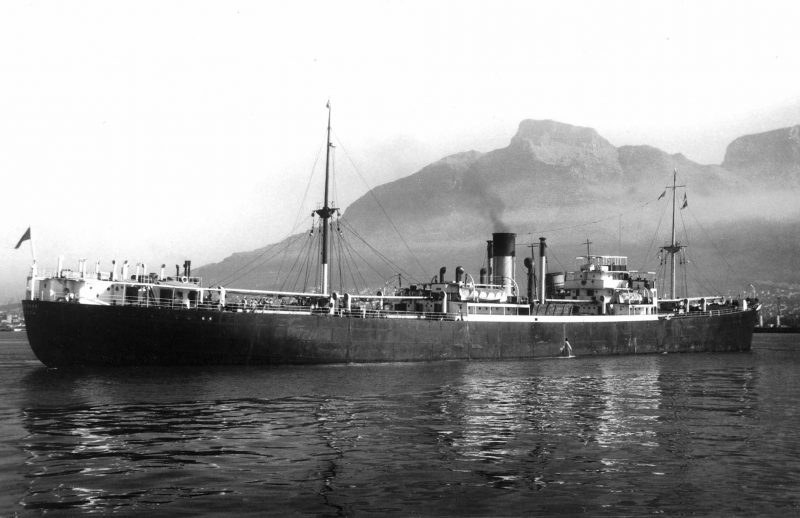

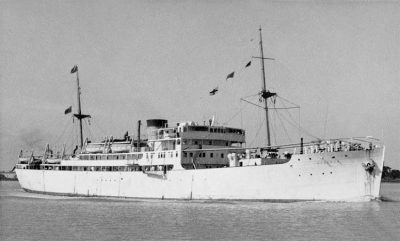

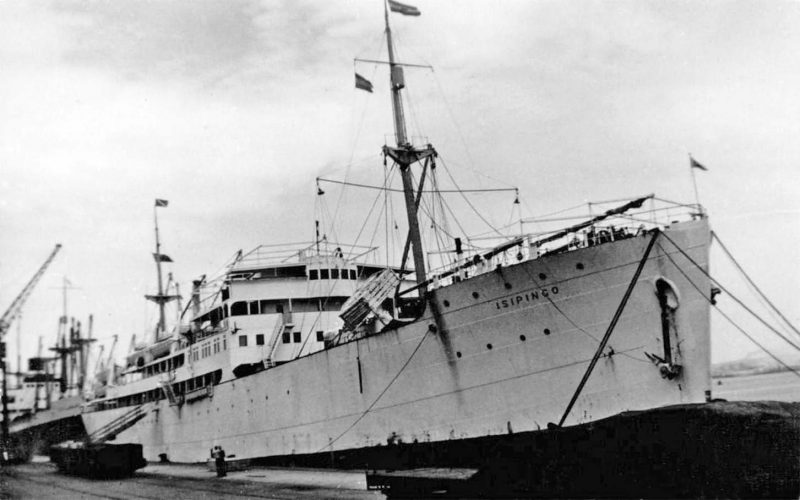

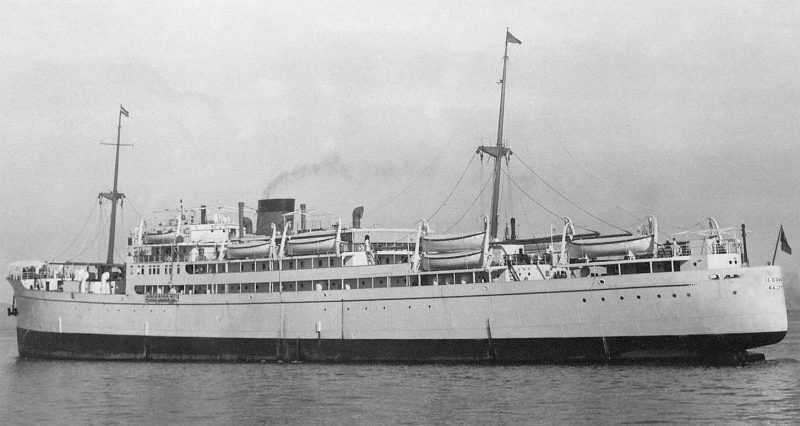

Andrew Weir, the great shipping entrepreneur, and his board ordered 3 passenger cargo vessels from Workman Clark in Belfast for delivery in 1934. It was a departure from the usual focus on their worldwide cargo services – Liner and Tramp trades, and these ships were destined for the Indian/African service, to replace the Gujarat class and ex Bucknell, Natal Line ships that had been maintaining this service previously. The terminal ports were Calcutta at one end and Cape Town at the other, but it was a flexible arrangement with interesting deviations as the need arose. Durban later became the regular turn round port. A significant improvement in fittings and comfort was planned for the 50 first class passengers, and the 20 second class. Up to 500 deck passengers were also catered for in the ‘tween decks. Much was made at the time of the features for the first class which included en-suite bathrooms and a glassed-in tea room. Fresh water baths, not always available in pre-war ships were also provided. Some sixteen years later when sailing on the Inchanga, the impression was distinctly Somerset Maugham-ish with much spacious polished wood, and a hushed and relaxed atmosphere, no doubt partly due to the relatively few passengers. The vital statistics were 7,300 tons gross, length 435ft, breadth 57ft, draft 37ft. Twin screw 6 cylinder Workman Clark SD 60 diesels gave a speed of approximately 15 knots. Before the passenger numbers were reduced many years later, these ships had 12 lifeboats with double stacking on the afterdeck. It was an awkward arrangement which called for the launching of the top boat and then the need to rewind the davits back to hook on the lower boat. The number of boats were slowly reduced over the years as the passenger capacity was changed downwards.

When the war started a few years later, there were interruptions to their intended route, and the Incomati was sadly torpedoed and sunk by gunfire off Lagos by U508 in 1943, having survived the first 4 years of hostilities. The radio officer died in the attack, but passengers, crew, and naval gunners, were eventually picked up by British destroyers. The Inchanga and the Isipingo went on to dodge the submarines and surface raiders, and had a successful 30 year career, largely running as intended between India and South Africa. The demands of war meant they occasionally deviated in those early years, joining Atlantic convoys with all the associated risks, and visiting New York and Liverpool.

I was to join one of these almost unique vessels, the twin screw Inchanga for a full year in 1951. Little did I realise at the time, but the sea school I attended had secured an apprenticeship for me in one of the most iconic British shipping companies. Not a household name like P&O or Cunard, but the relatively unknown Bank Line with a fleet of 50 ships covering the globe. It was to be a priceless experience.

Arriving at the ships gangway I was still 16, and very green, but writing this some 66 years later, the evocative spice laden smell that characterised the Inchanga is still easily conjured up. The wide wood- sheathed alleyways on the main deck had very large and low ventilator cowls, and these gave out a heady perfume of cinnamon, nutmeg, and other spices in a rich aroma. As with all perfume the intensity varied, and when the hold spaces was filled by tea chests, for instance, the familiar and pungent smell of Broken Orange Pekoe and other blends would dominate. This feature, unseen, but omnipresent, is easily the most powerful recollection for me.

Joining a few days before Christmas 1951 in Calcutta, I had been plucked from a ship in Adelaide, and travelled north via Ceylon on the S.S Hazelbank. a coal burner, ex Empire Franklin, which took me to Colombo. Then it was onwards in a relatively new addition to the fleet, the Westbank.

Although only a few months at sea, luck or maybe bad luck, made me the senior apprentice on board the Inchanga, as I was replacing an apprentice out of his time, and returning home to sit for second mate’s ticket. My cabin mate was a South African lad fresh from the highly regarded General Botha sea school. We were to become friends, and he went on to be head of the South African ports organisation.

Within a few weeks, I was told that I would be acting third mate. Shock, horror! There was I still working out my ass from my elbow at 16, and I was catapulted up to the bridge deck to keep the 8 to 12 watch. In the event of course, all went reasonably well, especially as there were sympathetic fellow officers to lend a helping hand. The second mate at that time was a rare bird, who managed the Herculean task of sitting his tickets effortlessly without recourse to school. He was later to rise up to become the company superintendent for South African ports. To set the mood of life in 1952, there is nothing better than the pop tunes of the day, and I recall that Johny Ray was all the rage, singing about ‘Just crying in the rain’ and ‘The little white cloud that cried’. Other hits were Jim Reeves with ‘I love you because’ and Guy Mitchell with his ‘Red Feathers’!

Life on board the Inchanga for me fell into a pattern. The stint as third mate lasted only briefly, when I reverted thankfully back to apprentice duties. However, on the bridge watch there was one memorable night sailing through the Maldives Islands which is burned into my memory. Down below a party was in full swing, and I could hear the muted music and laughter from the saloon. The Captain had a reputation as a ‘Lady’s man’ so it all fitted. On the bridge we were swooshing silently through the tropical night, phosphorescence in the bow wave, and a balmy breeze out on the bridge wing. At this time, the Inchanga had yet to be fitted with radar, so we were sailing blind through a quite narrow passage and relying on the last star sight position, which meant that I was hanging over the bridge wing straining my eyes to see any sign of the islands or surrounding reefs. I was apprehensive in the extreme. Events in the Bank Line fleet over the next few years more than justified my terror, as it happened. There seemed to be a fatal attraction to the many islands we visited, lit and unlit, with consequential casualties.

Back as apprentice, a twice daily routine was the unlocking of water taps for our Asian deck passengers. The drill was to stand by the pumps and monitor the queue. Quite often, chickens were slaughtered by the pumps and the water used to flush the blood away into the scuppers. The chicken had its throat cut in a ritual and was then usually dumped in a wicker basket where it slowly died making croaking noises. After the initial shock of this practice it became a regular occurrence and a normal event. There was no trouble with the often large numbers of deck passengers, but there was a crush, with teeth cleaning and energetic ablutions going on in a haphazard fashion. I also remember a box on the toilet bulkhead where a queue of passengers dipped in a wet finger and then rubbed their teeth, which were usually pristine. I was fascinated. Memory tells me this was fine sand, but on reflection, could it have been? Maybe a tooth powder. In the ‘tween decks they were assigned a space which was not much bigger than their bed roll, and I was amused at the way each space was regularly swept clean, but leaving the debris a few inches away from the designated area.

In the traditional way of apprentice boys we carried out a variety of tasks around the decks and in the holds, sometimes assisting the Chinese carpenter, and sometimes working alone, painting and scrapping, or servicing the lifeboats. This involved the regular replacement of the water, biscuits, and barley sugar kept under the thwarts in special tanks. Applying Stockholm tar to tanks, or setting up cement boxes was another task. The senior apprentice received orders for the day’s work from the Mate, and then it was just a matter of getting on with it. Occasionally, it was possible to speed up the work so that the rest of the day could be free time, but it always depended on the mood and whims of the Mate. Sometimes, things went horribly wrong, as when I mistook instruction to sand down a door and re-varnish it. I chose a highly polished door leading into the dining saloon when it had been intended to work on one of the outside doors. It had seemed odd to me, but orders were orders I reasoned! It was only put right in Calcutta by skilled polishers, as one of a myriad of jobs on a long repair list.

We rarely mixed with the passengers, but there were moments. Mostly, the passengers were returning or joining civil servants and sometimes they travelled with their children or relatives who were more in our age bracket. There was one particular girl that we all fancied, including the Mate, who unfortunately for us youngsters pulled rank. On the main deck along the starboard side was a double cabin for the apprentices, and it was conveniently opposite the barber’s shop which also stocked sweets and snacks. Never mind that the chocolates, kept in the warm, were soon covered in a white deposit of mildew, we still scoffed them all when funds would allow. Next door to our apprentices cabin and separated only by a thin bulkhead was a particularly randy and predatory electrician whose aim in life appeared to be the pleasing of any needy lady passengers. He entertained us regularly with the sounds of his energetic lovemaking.

Our route from Durban to Calcutta and back took in many ports up and down the East African coast, and anchoring played a major part in our progress. Anchoring was also regularly resorted to on the Indian and Bangladeshi ports in the Sunderbans, Chittagong being the most important where we often loaded very heavy bundles of tough, shiny, straw coloured Jute, and bales of Gunny bags for East African ports. Work went on through the night, and one of our duties as apprentices was to ensure that the gangs in the holds filled all the space right up between the beams, not an easy task. This was accomplished by many hands all working in unison to repetitive chants, not unlike European sea shanties of old, with a leader calling out and a chorus responding. It was impressive and usually carried out with good humour and diligence. By this means, prodigious weights could be lifted up and rammed home. Lighting was provided by portable clusters as they were known, and these had a circle of bulbs for maximum effect. Keeping the bulbs replaced and re-positioning the clusters around the hold was another job for the apprentice on duty, and in a tropical downpour it could be dangerous and unpredictable as they became soaked and shorted out. Our Chinese carpenter amused us by sticking his fingers in the sockets to set for power. The Inchanga and her sister Isipingo were designed with 4 small reefer spaces in number 4 hatch ‘tweendeck, and these were in regular use for a variety of produce in bags. I can recall freezing nights in these spaces tallying bags in and out, whilst outside it was the lovely balmy atmosphere of a tropical night . The temptation to step outside was countered in the knowledge that pilfering or irregularities could so easily occur. It was a relief when the heavy thick doors of these lockers, as they were called, were finally slammed shut.

Arriving and leaving port my role was assisting the Mate on the foc’sle, and I had personal charge of the anchor buoy which served such a useful role in fast flowing muddy waters. This was simply a wooden float attached to an anchor fluke by thin wire, and coiled up and secured on the rail ready for use. When the anchor flew out, the twine lashing broke, and the buoy would usually give us a tell tale location of the anchor on the bottom. It was a rough and ready tool which often went wrong but it was useful in the main. I learned a lot in that year about anchoring, and the fascination for a youngster like me at that time was the variety of trash that came up on the flukes. Everything from other peoples’ anchors, i.e. those from nearby ships, to ropes and wires, and debris of all sorts. When the windlass started straining loudly, I knew we had caught a big one! Washing tons of mud from the flukes with a hose was part of the fun. It also happened that we often needed to unshackle the anchor to attach the chain to river buoys in some of the ports served.

On the African coast, we usually had a leisurely stop in Mombasa, where the pace of life in the port was slow and measured. It was the days when B.I.’s lovely Kampala and Karanja were often in port and we might easily be on the next berth dwarfed by their size and opulence. It also meant time for relaxation, playing table tennis in the seaman’s mission, or a trip up Port Reitz in the motor lifeboat when we swam and drank beer in the Port Reitz hotel. Looking back, I also recall loading bags of raw asbestos from the inland mines, long before the warnings were sounded over the dangers of this material. Further down the coast, stops were made at Zanzibar and Dar es Salaam, and often in the minor port anchorages of Linda, Tanga, and Pemba. It was idyllic but short stops meant constant anchoring and stopping and starting. Beira was a major call, and strangely we often suffered the dreaded wait for a berth, anchoring off in the bay. This seemed strange, because our passenger status and network of agents usually ensured that we were able to ‘jump the queue’. Not here though, and I recall working on deck in sweltering heat and being bitten by Tsetse flies which could easily sting through the shirt. Next stop south would be Lourenço Marques, now Mobutu, and these two ports were pleasant stops with great local beer often served up with a variety of snacks including beans. They were railway ports with tracks coming down to the quay with copper bundles and other produce.

Durban was a great port, the seafront hotels and bars looking most welcome from seaward, especially at night with all the magical twinkling coloured lights. The port is marked by the famous Bluff, and this represented home, or as near as we could get to it. We often had valuable trans-shipment cargo to discharge and our job as apprentices was to remain down the holds to try and prevent pilfering. Silks and clothing from Japan were in bundles, and I recall fashionable shoes packed in boxes with the left ones together, and the corresponding shoes in separate cartons, presumably to also deter pilfering. On one occasion during one of my stints in the hold, the labourers, always in great fettle, laughing and singing, crammed two left shoes on their feet. Then they climbed out of the hold at the end of the shift dressed in gaudy silk scarves and dresses, still laughing and singing, and attempted to run the gauntlet of the strict dock guards. It was hard not to admire their temerity and their high spirits.

At the other end of our approx. 12 week run was Calcutta and a special life for several weeks. Special and different because that was where running repairs were carried out, also drydocking if due, and the intensity and vibrancy of Calcutta meant life was generally disrupted, like it or not.

Arriving in the brown and sometimes turgid waters at Sandheads, the first sight would be a gaggle of ships anchored and waiting for a berth. Any delay here would be short, and we would take a pilot for the long and tortuous route up the Hooghly river. The pilotage was always a challenge due to the ever changing mud banks, and we usually anchored halfway overnight before proceeding up to the city. Starting either in Kiddapore or King George docks, we would usually shift out to the river buoys to load. More often than not, it was necessary to strengthen the moorings to cope with the bore tide which is a feature of the Hooghly, bracing ourselves for the surge of water as the incoming tide overcame the normalcy into outflow. Carcasses in the river were a common sight, including the occasional human. Often a hawk would be perched on the bodies, as they flowed silently downstream. If a drydocking was on the cards, life could be seriously disrupted as trips to shoreside toilets became necessary, and the hammering, banging and sometimes riveting invaded the peace. Trips ashore in the evening meant negotiating the hordes of youngsters with their hands outstretched chanting the regular mantra “One Anna, one Anna, one Anna”. Despite all this, I have fond(ish) memories of the time, walking past compounds with lilting Indian music in the air, along with the fire smoke. Up in the main street of Chowringhee, life teemed with roadside barbers and hawkers offering all sorts of goods and personal grooming like massages and ear clearing. Here on a memorable day in 1952, I saw ‘Singing in the Rain’ with Gene Kelly, and for an hour or so I was transported to another world a million miles from the daily bustle onboard ship. It was magic at the time. There was also a great open air bar with cabaret which had the same effect on me. Looking back, I must have been in a fragile emotional state.

Eventually, after my time away rose to 18 months, someone back in head office decided that I would leave the Inchanga in Durban for a trip home co-incidentally on the Westbank, again. She had just been dragged off of the island of Juan De Nova in the Mozambique Channel where she had run up an unlit beach in the night. It was touch and go, but the salvage eventually succeeded and she was patched up in Durban. Huge steel girders were welded along the side at bilge keel level, and for good measure she was then loaded with a full cargo of Manganese ore for discharge in Immingham. Not a cargo usually associated with a damaged ship, but the necessary clearances would have been obtained.

So ended my first trip in the Bank Line. It had taken in 5 ships and lasted nearly 20 months, which included the fascinating spell on the unacknowledged flag ship of the company. Maybe this title would be disputed by all the Isipingo veterans. However, like all voyages in the Bank Line, it was not so much a routine trip, but more like a full blown adventure.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item