by Peter Hay

When I finished my pre-sea training I had to wait a couple of months before starting as a cadet with Blue Star. Being keen to start I looked around for a job to fill in the time.

As I lived in Newcastle the colliers seemed to be the answer. Short trips and home regularly, no chance of signing on and then finding that the ship was ‘going foreign’ and that you could be on board for two years before being repatriated. After two days of running around, being interviewed, filed, photographed etc. and having to join the British Union of Seamen, I became a Deck Boy. The ship, the Arundel was a modern one. I had my own cabin (the last time I had that luxury for three years) and the work was not too hard. I cannot remember what the food was like but it must have been okay as I can remember the bad feeders!

One thing that I did not appreciate at the time was that it had a washing machine. Later on as a cadet on a spartan war time built ship I can remember doing my ‘dhobi’ (laundry) in a bucket using a Lonnie Donnegan style washboard and thinking wistfully of the washing machine.

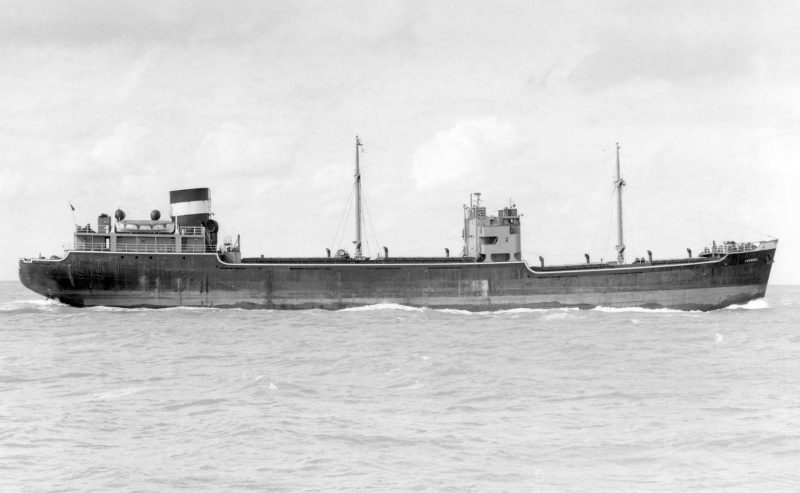

After finishing my cadetship with Blue Star I came ashore for second mate’s. When the summer holidays came I opted to go back to sea to earn a bit of money and I went back to Stevie Clarkes. This time I was going to be uncertificated second mate. I joined the Cowdray at the lay-by berth in Hartlepool. When I reported to the ‘Old Man’ he told me that in an hour we were going to shift ship from the lay-by berth on to the loading berth. It was an L shaped wharf and we had to swing through 90 degrees. He then took me out on deck and showed me where all the mooring lines were going to be run from and to. I was used to just going onto docking stations and getting a string of peremptory orders issued over the phone and I was impressed that I was being given a thorough briefing first. When I went out for docking stations after an hour I found out why. Everyone else had gone home and there was just the duty AB and myself to do the shift ship. The ship was not big, 1,748 tons gross, but even so it kept you on your toes. I was at the stern and had to heave on the spring line which pulled us ahead, while simultaneously slacking down on the stern line which led aft. This had to be done in conjunction with the AB on the foc’sle who was doing the reverse. As well as moving the ship ahead we had to stop her from moving too far away from the wharf. We had wire compressors which were a great help, but we did not have communication between us, so as well as looking after your own end of the ship you had to think in tandem with the man at the other end. When the correct hatch was underneath the loader the foreman blew his referee’s whistle and we made fast.

On the next voyage we went into Seaham Harbour and we had a very old tug to assist us. It was a paddle wheeler with an open bridge, only for the hardy in that climate. A few years ago I saw one of them which had wound up at Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco, because it was similar to the ones they had used in the days of sailing ships. They had bought it and restored it. To load the coal the wagons would be uncoupled and winched one at a time up a ramp to the top of the shute. The wheels would then be clamped and the wagon tipped over 45 degrees. The ‘Pin Man’ would then knock the pin out of the side of the wagon which would hinge open and 9.9 tons of coal would thunder down the shute. The remaining 0.1 ton of dust would scatter itself indiscriminately, but comprehensively, round everything in sight. A far cry from the 6,000 ton/hour conveyor belts I got used to later on. In the same way I can remember the Chief mumbling into his cornflakes at breakfast about the Welsh bunkers. The penny dropped.

“Is this ship coal fired?” “Of course it is you silly young pup”. I had thought I would never sail on one. 30 years later I commanded 2 coal fired ships that were 25 times the size.

We sailed the following night and the mate said he would keep the first watch. there were only two mate ships so you worked ‘watch on watch’, 4 hours on, then 4 hours off, and split the afternoon dog watch, so I came up at midnight. As I came through the wheelhouse door I got a sinking feeling. There was a blaze of lights ahead. It was the fishing fleet coming out of Whitby, and extended right across the horizon in front of us. The mate thrust a pint china mug of tea in my hand – they were the sort of ships where a demibucket would always be preferred to a demitasse, and said we are here on the Decca and I am off. Having just been to College I was expecting the usual 15 point handover.

At this point I should say that they were used to getting reliefs who were experienced on that trade. Still waking up I got the first question off as he was going down the stairs “What is the course?” The answer echoed back up the stairs, “NE by E a quarter East.” I knew what quarter points were, I had read my Hornblower, but I never thought I would have to use them. Those ships were an unusual mixture of very old and very new ideas. I think they were the first ships to use steel Macgregor hatches, instead of wooden hatch boards and tarpaulins, before WW2, and they were quick to get Decca Navigator. On the other hand there was no gyro compass-only magnetic, and of course no auto pilot. In port they would shut the generators down at night and you had to use ‘bulkhead dynamos’, paraffin lamps.

I came up to relieve the mate on an afternoon dog watch and found the ‘Old Man’ had the watch. We were passing the Goodwin Sands and there was a bit of traffic around. After looking around to get my bearings I saw that something was not right. “Captain I think that buoy is on the wrong side.” “Why aye bonny lad, we always gan doon this side, it keeps us out of the way of those big boogers over there”, pointing to the deep sea ships jostling for position on the correct side of the buoys. With our comparatively shallow draft we could sail close to the buoys on the wrong side and still have enough water, while keeping out of everybody’s way. This was a technique that I found was used in the Great Barrier Reef when I started piloting there many years later. It works well, but you have to know what you are doing.

On another occasion I saw a light coming up over the horizon and I started counting the flashes, to identify it. Every light has its own distinctive pattern of flashes, and in the North Sea in summer with good visibility there can be dozens in sight which makes identification confusing. In winter with bad weather or fog you would give your eye teeth just to see one. A conversational voice from the man on the wheel said, “Eh lad, the Dowsing Light has come up a bit early. There must be a bit of fresh in the ebb.” Not only had he identified the light without having to consult the Light List but he had worked out that the tide was a bit stronger without looking at the Tide Tables, and then given a reason for it. Not for the first time I thought “What the hell I am doing here when the man on the wheel knows it backwards.”

The last time I sailed with them was a few years later when I got back from the Far East and was filling in time looking for my next deep sea job. I joined the ship in Burntisland on the Scottish East Coast. The ‘Old Man’ was in his early 40s, and as such, was one of the youngest people on board. “You look a fit young fellow, do you play golf? No, well you want to learn don’t you? We will leave the mate to load the ship and we will go and have a game”. Put like that, golf had an immediate appeal. I recognised the signs. There is nothing more zealous than a middle aged convert to either sport or religion, and golf is both. I duly hacked my way round half the bunkers on the local course. The only reason I did not find the other half of them was that I could not hit the ball far enough. After we sailed I got a bit of shock cord, a length of boat lacing (light line), a coir doormat, and nicked one of his golf balls. I put the whole lot together and said, “Look captain, a practice driving range”. He was well pleased but of course he could not use it then.

The Hackney was one of those flat iron colliers. It was built to go under 9 or 10 bridges on the Thames to get to Battersea Power Station. It was a sort of nautical limbo dance. Starting from Tower Bridge each bridge got progressively lower. At some stage the masts and funnel were lowered and it was something like 15 feet from the waterline to the top of the monkey island. Going up river loaded you had to go at high water to have enough to float on, but coming down river lightship you had to go at low water so that the upper works did not hit the bridge. Needless to say at sea you were semi-submerged most of the time. A nasty side effect of this was that the bridge wing doors were hermetically sealed to stop the leaks. This emphasised the fact that a lot of them smoked shag tobacco. I was on watch when we entered the Thames. The Captain, as a regular trader, had sat the pilotage exam so he did not need a pilot. At about Sea Reach Buoy No. 3 the ship started to re-emerge and the ‘Old Man’ said, “You have been up the Thames before haven’t you? I will be on No 2 hatch if you want me”, and off he went happily hooking and slicing. One of the useful things about being on a small ship with a low height of eye is that to cross check your position you can do what the ‘yotties’ do, and sort of sidle up to a buoy and read the name. I could, of course, have asked the man on the wheel, but a man has got some sort of professional pride hasn’t he?

After a couple of trips I was fixed up with my next deep sea job and off I went. I still have a soft spot for the ‘Silver Banders’ and the men who sailed on them.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item