By Ken Williams

![]() During the early 1970s, Britain was in the grip of a downward economic spiral with never-ending strikes and rising inflation. To many seafarers, like myself,

During the early 1970s, Britain was in the grip of a downward economic spiral with never-ending strikes and rising inflation. To many seafarers, like myself,  visiting other English-speaking countries appeared to offer more opportunities for advancement and in most cases a better life in the sun. In January 1974, I took some unpaid leave in order to explore southern Africa as a potential place to live and I eventually ended up in Salisbury, Rhodesia. In April of that year, Portugal announced a withdrawal from her overseas territories in Africa, following a military coup in Lisbon. This sent shock waves throughout Rhodesia, as the country now faced an additional counter-insurgency campaign against groups of armed guerrillas along its long border with Mozambique. With no political solution in sight, I decided to return to the UK and complete the second engineer’s Certificate of Competency course. A single air ticket to London from southern Africa was prohibitively expensive so I thought a cheaper alternative would be to work my passage home from a South African port. For this I needed my discharge book and British seaman’s ID card, which my father duly sent me.

visiting other English-speaking countries appeared to offer more opportunities for advancement and in most cases a better life in the sun. In January 1974, I took some unpaid leave in order to explore southern Africa as a potential place to live and I eventually ended up in Salisbury, Rhodesia. In April of that year, Portugal announced a withdrawal from her overseas territories in Africa, following a military coup in Lisbon. This sent shock waves throughout Rhodesia, as the country now faced an additional counter-insurgency campaign against groups of armed guerrillas along its long border with Mozambique. With no political solution in sight, I decided to return to the UK and complete the second engineer’s Certificate of Competency course. A single air ticket to London from southern Africa was prohibitively expensive so I thought a cheaper alternative would be to work my passage home from a South African port. For this I needed my discharge book and British seaman’s ID card, which my father duly sent me.

Entry into South Africa could be difficult for those with insufficient funding to support themselves. I was told that it might be less hassle to enter through South West Africa (now Namibia), a journey from Salisbury to Cape Town of over 2,000 miles, via the Kalahari Desert. I left Salisbury with a rucksack, a sleeping bag and around £30 in my pocket. Lifts across Rhodesia to the border at Botswana were relatively easy to come by, in contrast to the infrequent chances of transport across the 600 miles of the Kalahari Desert that lay ahead of me. At one small native village in the desert, I was stuck for three days before I could hitch a ride squeezed into the back of a pick-up truck which I had to share with a goat.

Eventually, I arrived at the small South West African border post from Botswana where the South African border guard asked me what my business was in South Africa. I said I was on leave in Rhodesia and was joining a ship in Cape Town. After examining my seaman’s papers, he granted me a month’s stay in South Africa.

The road leading to Cape Town did not have much long-distance traffic, except for Portuguese settlers fleeing from Angola and they normally did not have enough room for me amongst their worldly possessions. However, once I crossed into the Cape Province, lifts became easier to get and I soon made it to the Seaman’s Mission in Cape Town. The Mission padre could only offer me a shared room at just over a rand (£1=1.6 rand) per night. He asked me with some trepidation if I was willing to share the room with a coloured man. My roommate turned out to be a very pleasant fisherman who was waiting for his next boat. The padre kept me informed every day of the shipping movements in the port. The only vacancies available for an engineer were on a Greek-flagged vessel going to the Mediterranean and on another ship bound for Indonesia.

I tried the local offices of British shipping companies trading with South Africa. The Harrison Line Agency were not aware of any vacancies in the near future. In the British & Commonwealth Group office, one of the superintendents said to me that the Company would be reducing its fleet, leaving little scope for further recruitment.

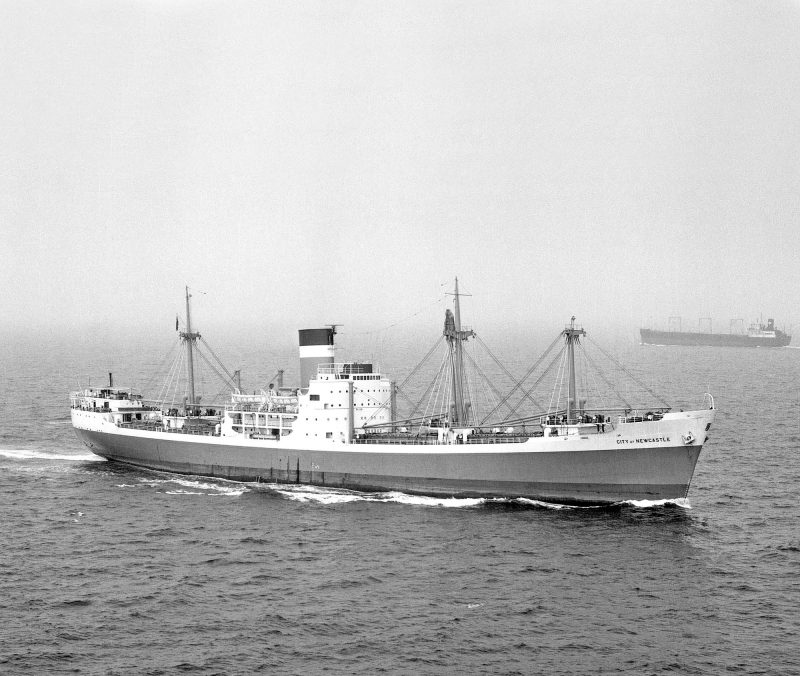

My final call was the Ellerman Lines office, a company I had sailed with three years earlier. There I met Captain Tony Wetherly, who was sympathetic when he heard my predicament, and offered to send a telex to London asking about any possible openings for engineers. With less than two weeks left on my South African permit. I proceeded to call at the Ellerman office every morning to find out if there had been any response. At last there was a short message: “What has Williams been doing since he left the Company in 1971?” Tony and I put together a brief employment history and sent it off by telex. There followed further days of waiting before finally, with only a few days left on my permit, a message came back from London: “Williams to join City of Newcastle as 4th Engineer at Mombasa on 1st July 1974.”

Ellerman City Line operated an altruistic personnel policy, whereby if any of the sea-going staff suffered any personal or emotional problems the Company would, in most cases, repatriate them home from anywhere in the world. I was later to find out that two of the junior engineers had been flown home for personal reasons, hence the opening for a fourth engineer.

The Ellerman office made all the travel arrangements for me to join the ship. I was to fly from Cape Town to Johannesburg, transfer there to Nairobi and then on to Mombasa. At each stage of the journey an Ellerman agent would meet and guide me to the next departure gate. A problem arose at Nairobi Airport when the agent did not recognise me. At the time, I had long hair, was wearing worn jeans and had a rucksack with two bushman spears attached. A call was made for me to report to the Information Desk. The agent’s immediate reaction was that while he had seen many seafarers he had not seen one dressed like me.

From Mombasa Airport, the local agent drove me directly to the ship, where I was directed to the Captain’s cabin. I knocked on his door and said I was the new fourth engineer. He looked me up and down as I stood in his dayroom and exclaimed.

“Good God! What is this company coming to?” “Where is your uniform?” He enquired.

“I haven’t got one,” I politely replied.

“You can’t eat in the officer’s saloon. You’ll have to eat in the duty mess with the carpenter,” he said.

I was shown to my cabin and unpacked the few possessions I had. Then I went down to see the Chief Steward for a sub. He quickly replied, “You have only been on here for five minutes and you want a sub!”

That evening, I went up the road and bought myself some working gear from the Asian traders, and later joined the engineers in the ‘Sunshine Bar’ along the Kilindini Road. It was an establishment that could easily be identified by the sound of a long hiss uttered by a young woman at one of the windows to any passing potential customer, which was swiftly followed by the name ‘Johnny’.

Early the next morning there was a knock on my cabin door and outside stood the old carpenter. He asked if he could have a slug of whisky. I gathered he must have found out that I had got a bottle of Scotch whisky from the bond. I poured some into my travelling beaker and offered it to him. He said in a quiet voice. “Could you fill it up a bit more?” After giving him a good measure, he downed it in one go and as he left my cabin for work said, “I feel a lot better now, Fourth.”

The City of Newcastle was one of a group of six cargo vessels specially designed for the company’s Eastern service. They were all powered by a six-cylinder, Doxford opposed-piston engine giving a service speed of around 15 knots. I had previously sailed on the first ship of this class in 1971, the City of Colombo, to the same east African ports of Zanzibar, Dar-es-Salaam and Mombasa. Time spent on the coast was up to two months, which usually gave enough time for the planned maintenance. The Second Engineer was John Elder (Bluey), an Australian who had served for many years on the Company’s four passenger/cargo ships, known as the ‘big four’, on the London to South Africa service. He possessed a wealth of experience working on Doxford engines and had the machinery overhauls down to a fine art, so much so that all the scheduled maintenance and other jobs were completed four days before sailing back to the UK. This enabled us to relax around the swimming pool at the Seaman’s Mission or hire a Land Rover and go on safari for a few days.

Loading for the UK started in Dar-es-Salaam with Zambian copper ingots stowed in the lower holds for deadweight and stability, and on top of this was a high-volume cargo consisting of chests of Kenyan tea which completely filled the holds and meant that a pleasant aroma of tea permeated the ship for many days.

The watch-keeping engineers now consisted of a second engineer, three third engineers, a fourth engineer and only one junior engineer. Since I was the fourth engineer I was given the junior position on the 8-12 watch. Each sea watch comprised of two engineers assisted by a Panni-Wallah whose main tasks were associated with the donkey boiler, such as maintaining steam pressure and safe water levels in the gauge glasses mounted on the side of the boiler and a Taile-Wallah who attended to the generators and other auxiliaries. The rest of the crew were on day work and were made up of a Serang who controlled ten men mainly assigned to cleaning duties, and a Cassab in charge of the engine-room stores. All the Indian complement were housed beneath the poop deck, whilst their galleys, WCs and hospital were in the deckhouse above.

The homeward-bound voyage, via Durban for bunkers, was uneventful, except for a couple of instances. The first was a generator uptake fire on leaving Mombasa, during the afternoon 4-8 watch, which caused the engine-room to start filling with smoke. When I arrived at the platform above the generators, the Second Engineer and Third Engineer were calmly walking around the generators monitoring the situation, as though it was something they had both handled many times before. The fire was allowed to burn itself out by keeping a constant steady load on the generator affected.

The second incident occurred off the coast of Brittany when water was detected in the main engine lubricating oil flowing through the purifier. Unfortunately, water contamination, inside the crankcase, from a leaking swinging arm pipe on the lower piston cooling water system was a perennial problem on this type of engine. A planned stop at sea was made the following morning to carry out a crankcase inspection. After removing the crankcase doors, a visual inspection soon traced the leak to an elbow joint on a swinging arm pipe leading to one of the pistons. The joint was repacked by climbing inside the slippery crankcase in an atmosphere of hot dripping oil. However, on the subsequent Doxford engines, water contamination of the lubricating oil was minimised by using oil as the piston cooling medium.

On arrival at Hull, on the 23rd September, I paid off and a few days later enrolled on part ‘B’ of the Second Engineer’s course at Poplar Marine College in London. At the end of the course, I went round to Ellerman’s main office in Camomile Street to inform the personnel officer that I had just passed the Second Engineers’ Certificate. I was warmly greeted with, “Congratulations, I suppose you want a second’s job now!” Fortunately for me, there was a chronic shortage of chief and second engineers at sea holding Certificates of Competency. This shortfall was alleviated by employing uncertificated engineers, on the recommendation of the shipping company concerned. They were given an oral examination by the then Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) and, if successful, were accepted in lieu of certificated engineers. Consequently, the DTI issued hundreds of these ‘Dispensations’ each year to engineers, most of whom were known as ‘professional thirds,’ to sail as second engineers.

In 1991, I had a survey to do on a passenger ship berthed at Cape Town and took the opportunity to find Tony Wetherly, if he was still there. After a number of enquiries, I discovered he had moved to Durban. When I finally reached him, we had an interesting telephone conversation about the changes that had occurred in our lives and I thanked him again for his invaluable help in getting me back home from Africa.

The 7,727grt City of Newcastle was built in 1956 by Alexander Stephen at Linthouse. In 1968 she joined Ben Line for 3 years as Benratha before returning to Ellermans. In 1978 she was sold to Venture Bay Shipping and renamed Eastern Envoy. On 23rd October 1980 she arrived at Chittagong to be broken up by Bengal Shipbreakers Ltd. (FotoFlite)

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item