The survival of Great Britain during WW2, and the then known British Empire did, as we all know focus around being able to import sufficient food, commodities, ammunition, and other war materials during the period of conflict. The attempts to prevent freedom of navigation for Allied ships has been well documented, especially regarding the attempted U-Boat blockade by the Axis powers.

However, far too often has the crucial role played by the Norwegian Merchant Marine during WW2 been somewhat downplayed, albeit not intentionally, with most of the credit going to the British, American and to a slightly lesser extent the British Commonwealth nations such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Our Norwegian friends however, played a vital role in supplying Britain and other Allied zones of hostility with essential supplies, without which, the outcome of the conflict may have been very different.

More than 10,000 Norwegians, 9,379 men and 883 women, died as a direct result of the war. Only one- fifth of this number were derived from the Norwegian military. The highest single group of casualties among Norwegians came from their seafarers in their Merchant Navy. At sea, more than 3,600 civilians lost their lives, including 70 women. Consequently, seafarers made up more than a third of all the Norwegian war deaths. Their sacrifice was extremely important for the final determination of the war. This fact is often overlooked in the main mix of things and the Allies owe a real debt of gratitude for the sacrifices made by so many Norwegian sailors.

Of no less importance to the Norwegian campaign, was the sterling service provided by the Shetland Bus, a clandestine marine organization operated by the Norwegian fishing fleets and fisherfolk.

Norway’s policy of remaining neutral came to a prompt end on 9th April 1940, when Hitler’s Nazi Germany invaded the country, but the Norwegian Merchant fleet, the majority of which was at sea, in neutral or Allied waters, and ports, remained outside German limits of influence and control. Instead, the ships were requisitioned by the Norwegian government, and Nortraship was set up. This was the Norwegian Shipping and Trade Mission, based in London to administer the free Norwegian merchant fleet not under German control, which was frequently referred to as the world’s largest shipping company. The administration of the Nortraship establishment was undertaken by Senior Norwegian Shipping Managers, as well as British and American staffers.

The day-to-day operation of Nortraship was complicated and faced numerous challenges. The lines of command were difficult due to bilateral communication problems. On the one hand, information was vital to operate the fleet efficiently, whilst on the other hand, it was crucial that information did not leak out or fall into enemy hands. The final solution to this dilemma eventually became a wide network of Nortraship branches.

By the beginning of 1944 the Nortraship organization in London consisted of 17 individual departments, some divided into as many as five sections, whilst the New York office had 18 departments. Nortraship had 52 branch offices or representative offices, affiliated to either New York or London, located in 26 different countries.

Hence, the Norwegian Merchant Navy, their personnel, and ships played a vital role in the Allied fight against the Axis powers, but at a high cost. More than 700 ships were lost, and around 3,700 sailors lost their lives during the years of conflict.

The Norwegian seafarers and the fleet were pivotal during the Second World War, as part of the war effort, and as a source of funding for the Norwegian government in exile. Due to the mobility and global reach of Norway’s most important maritime sector, revenue could still be earned, even though the country was under occupation. The massive revenues earned from their ships that had been requisitioned, gave the Norwegian government in London resources that far exceeded what some other countries obtained.

The political situation under which the Norwegian crews rose to prominence was conspicuous. Although Norway was occupied by Nazi Germany, the sailors were working on behalf of Free Norway, aiding the Allied efforts at high risk to themselves. The Norwegian military had to rapidly give up their attempts at defending mainland Norway, but the ships and seafarers continued the fight. The transport of oil and petroleum products was particularly dangerous and difficult but significant to the Allied resistance and their ultimate victory.

The transportation of petroleum products formed the artery of the Allied fight for victory. In a frequently repeated quote, Winston Churchill claimed that Norwegian seafarers were worth more than a million soldiers. A substantial portion of the ships that were redirected by the Norwegian government were on their way to British ports at the time as there remained a robust relationship between Norwegian shipping and British trade. However, with the change in the conversion of the Norwegian fleet, from coal driven steamships to diesel driven motorships, it gave the Norwegian fleet more flexibility as it was no longer reliant of the coal supply from Britain as it had been in WW1. Moreover, a large share of the worldwide tanker fleet was Norwegian owned and operated, at around 40 per cent of the international tanker tonnage. This was a vital asset and would become particularly important for the provision of fuel for the British war effort. So, a UK at war, with an urgent need for sea transport to secure its survival, clearly summed up the situation at the time.

One prominent British politician, Philip Noel-Baker, commented after the war, “The first great defeat for Hitler was the battle of Britain. It was a turning point in history. If we had not had the Norwegian fleet of tankers on our side, we should not have had the aviation spirit to put our Hawker Hurricanes and our Spitfires into the sky. Without the Norwegian merchant fleet, Britain and the Allies would have lost the war”.

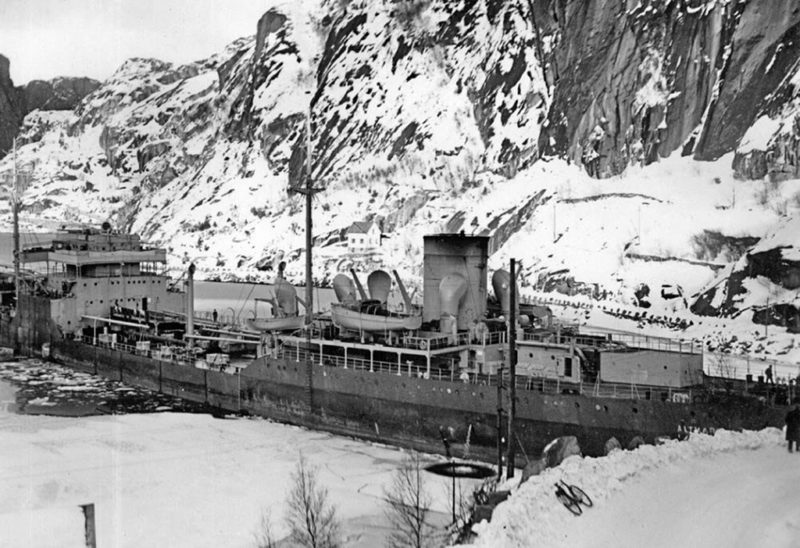

As a result of the limited military potential of the Norwegian naval defence and the strategic importance of the Norwegian coast, the British had already intervened and infringed upon Norwegian neutrality. In February 1940, British forces entered Norwegian waters and boarded the German vessel, Altmark (above), which was used to transport prisoners of war. Given that Norwegian inspections on three separate occasions had failed to discover around 300 prisoners that were secluded in the cargo hold of the ship, the British crosscheck and validation was therefore considered justified.

The Altmark incident provided Norway with a diplomatic dilemma, the case was a clear sign that neither of the belligerent nations really respected Norway’s neutrality. Slightly less than two months later this became patently obvious, when on 8th April, British forces placed mines in Norwegian waters, and a Polish submarine, which was part of a Royal Navy flotilla, torpedoed the general cargo vessel Rio de Janeiro, a ship full of German soldiers, off Norway’s South Coast. The approximately 300 German soldiers on the Rio de Janeiro were on their way to Bergen. A larger contingent of about 1,000 soldiers were onboard the heavy cruiser Blucher, which was also sunk in the Oslofjord, in the early hours of 9th April. The German invasion of Norway was, by this time, well underway.

The sinking of the Blucher bought time for the Norwegian authorities, including the government and King Haakon VII. They were able to leave Oslo and make their way towards the United Kingdom. At the beginning of June, the King, the Crown Prince, and including most of the government, arrived in Scotland from where they travelled to London to establish a Norwegian government in exile.

America’s entry into the war raised the question of the Norwegian tonnage, which then became a trilateral issue with British, American, and Norwegian interests all being considered. In late 1942 the remaining free ships flying the Norwegian flag were included more closely in the overall Allied theatre of operations. This situation during the short-term, strategic, and military ambitions and the long-term question of Norwegian competitiveness after the return of peace, became a delicate element of the Nortraship arrangement. After all, Norway was both an Ally and a competitor.

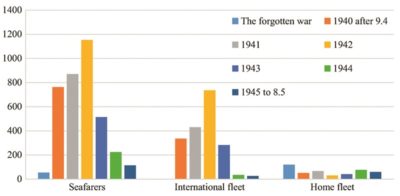

The above chart depicts the number of losses of seafarers, as well as ships from the Norwegian International and coastal home fleets, (the home fleet was mainly under the control of Germany’s occupying forces). The so called Forgotten War covers the early stages of WW2 between the time the UK declared war on Germany in 1939, and the time Norway was invaded in 1940, when there was much posturing between the warring factions but with limited hostility, nevertheless losses were sustained.

It should not be overlooked, when Denmark capitulated, their ships available to the Allies were confiscated. Greece in February 1940, and Sweden in December 1939 also entered into tonnage agreements with the UK, though the amount of their shipping capacity was much lower, than in the Norwegian case. The contribution made by the ships of the Allied nations of Greece and Sweden was, however, no less significant to the combined Allied war effort.

The Norwegian MV Torrens 6,713 grt (above). She entered service in 1939 under the management of Wilh. Wilhelmsen of Tonsberg. She was a modern twin screw motorship capable of a service speed of 17 knots. Torrens became part of the Nortraship agreement and served as a troopship between 1942 and 1946, operating on behalf of the United States War Shipping Administration by Barber Steamship Lines and the American West African Line. Torrens transported about 58,000 American troops to various areas of the Pacific, in over 20 voyages from the west coast of the US. On each voyage she had about 4,000 tons of cargo, mainly war materials and equipment for the troops.

MV Hoegh Merchant 4,858 grt (above) was built in 1934 and sailed under the management of Leif Hoegh & Co., Oslo. Hoegh Merchant was part of the Silver Java Pacific Line and also operated under the Nortraship arrangement, and had arrived in San Francisco from Manila on 9th November 1941. She discharged part of her cargo, then headed to San Pedro where the balance of her cargo was unloaded. Following a drydocking at San Francisco the Hoegh Merchant headed for Richmond, to load lube oil in drums, cement, and general cargo, in addition to 80 tons of TNT explosives, for a voyage intended to include Manila, Singapore, Batavia, Samarang, Sourabaya, Madras, Colombo and Bombay. Whilst at sea on 7th December (Pearl Harbor attack day) she was instructed to divert and head for a British, Dutch or American Port. This was later rescinded, and new instructions were later received directing her to Honolulu. In the late afternoon of 13th December, the Hoegh Merchant detected land right ahead, but not knowing the prevailing war conditions, the ship’s master stopped and drifted about 20 nm from Makapuu Point, to await further sailing directions and sunrise. The ship was still lying idle when she was torpedoed at 03.55am by a Japanese submarine, believed to be I-16. The torpedo reportedly struck the starboard side near No. 3 hatch. The captain asked the radio operator to contact the Navy Station in Honolulu, but no messages could be sent. Small fires broke out but soon extinguished themselves. However, 10 or 15 minutes later another explosion occurred in the same hold, believed to have been caused because water had seeped into the carbide stowed there. The Master ordered the ship to be abandoned. All 40 persons on board survived, including 5 passengers, and were rescued from the lifeboats soon afterwards by the American destroyer USS Trever and taken to Honolulu.

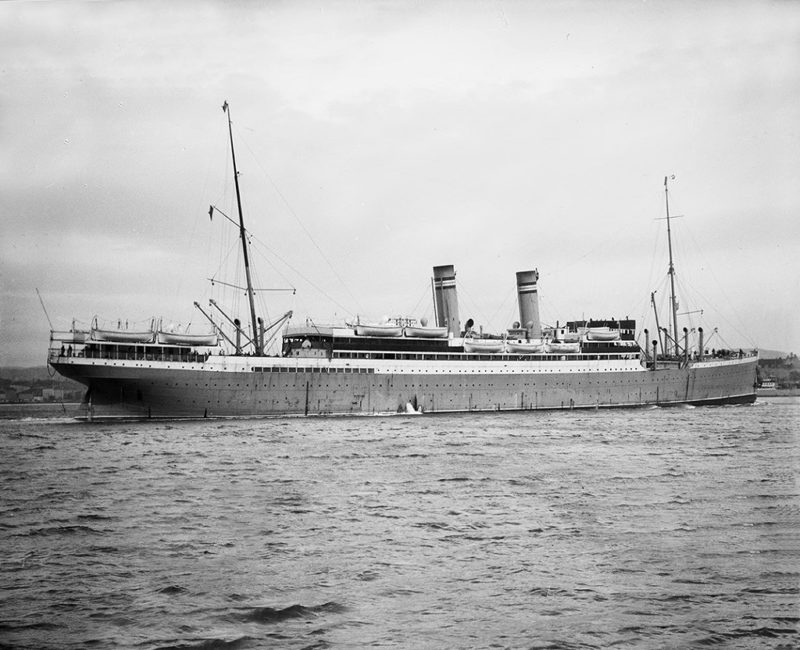

SS Bergensfjord, 10,699 grt (above) was capable of 15 knots and had a capacity for 1,200 passengers. She was a Norwegian ocean liner built by Cammell Laird in 1913 for the Norwegian America Line. She had sailed regularly between Norway and the United States. During the Second World War she was requisitioned by the British Ministry of War Transport (MoWT) and served with distinction as a troop ship between 1940-1946. She survived WW2 and after the war she continued sailing as a Trans-Atlantic passenger liner, first for South American owners, then for Israeli interests. She was sent for demolition at La Spezia in August 1959.

When Norway was invaded on 9th April 1940, there were several Norwegian ships in Swedish ports. Following the establishment of Nortraship, the Norwegian captains on the requisitioned vessels, including the ones in Sweden that were covered under the agreement, were asked to sign a loyalty declaration stating that they would hold these ships on behalf of the Norwegian government and would comply by Nortraship’s instructions.

Operation Performance was a British, partially successful operation for a break-out by Norwegian merchant vessels, supported by British warships and aircraft, from Sweden to the UK, set for 31st March/1st April 1942. Planned by the Special Operations Executive, this operation was a logical successor to the earlier operation ‘Rubble’ of January 1941, when five Norwegian merchant ships had broken out through the Skagerrak from Gothenburg and reached the UK under escort of two cruiser and destroyer forces dispatched to their aid by the British Admiralty.

Eventually, only two tankers, the 10,324 grt B.P. Newton and 461 grt Lind reached the UK. The 12,358 grt whaling depot ship Skytteren, 6,222 grt tanker Buccaneer, 1,470 grt cargo ship Gudvang and 1,282 grt cargo ship Charente were either sunk by German warships or were scuttled by their crews, while the 6,305 grt tanker Rigmor was bombed and sunk by German aircraft, and the 5,343 grt tanker Storsten was mined. The two remaining cargo ships, the 5,653 grt Lionel and 5,653 grt Dicto, returned to Gothenburg.

The secrecy under which this operation was conducted had major political repercussions. The Swedes were extremely vexed that the British government had masterminded and organized the illegal armament of the ships even though they were interned in a neutral country, and the Norwegian government-in-exile was very upset with the British about the loss of so many of their valuable ships. This was one of the reasons why a later plan, for the escape of the two remaining ships which had returned to Gothenburg, was abandoned.

The only sizable tanker to escape to the UK (Port of Leith) was the 10,324 grt B.P. Newton (above). She was built in January 1940 by Kockums Mekaniska Verkstads AB in Malmö, Sweden, for Tschudi & Eitzen. Of the 71 people onboard BP Newton which reached Leith on 3rd April, 13 were Norwegian stowaways. She served under the Nortraship agreement with distinction, during 1942 and 1943, when the ship traversed the Atlantic Ocean between Great Britain and America. She was sunk by the German submarine U-510 while sailing in Convoy TJ-1 off Paramaribo on 8th July 1943. The ship was laden with Gasoline when torpedoed and set ablaze. 24 of her crew were rescued whilst sadly, 23 others perished.

Much praise and recognition are also deserved by the Norwegian fishermen who provided a clandestine Shuttle between Norway and the Shetlands, using their fishing boats. This shipping link was to become a vital connection and later became known by the nickname Shetland Bus. The service was originally set up by the Norwegian Special Operations group and operated successfully between 1941, following the occupation of Norway by Nazi Germany, throughout the war years until 8th May 1945 when Germany surrendered to the Allies. The Shetland Bus was later absorbed into the Royal Norwegian Navy under the designation of Norwegian Naval Independent Unit (NNIU). The unit was operated initially by many small fishing boats and later supplemented by three fast and well-armed submarine chasers, Vigra, Hessa, and Hitra.

The main purpose of the group was to transfer agents in and out of Norway and provide them with weapons, radios, and other supplies. They would also bring out Norwegians who feared arrest by the Germans. Sometimes the group was involved in other special operations, like the failed attack on the German battleship Tirpitz, Operation Archery raids on Maloy, and Operation Claymore in the Lofoten Islands. The men put in charge of organizing the group were a British Army officer, Major Leslie Mitchell and his assistant, Lieutenant David Howarth RNVR. Upon their arrival they established headquarters at Lunna Ness, north of Lerwick

The North Sea crossings were mostly made during the winter months under the cover of darkness. This meant the crews and their passengers had to endure very heavy North Sea conditions, with no lights and a constant risk of discovery. This was a very hazardous and daring operation for the brave fishermen as there was a high possibility of being captured whilst carrying out the missions as they were always under continued threat from German surface vessels and patrolling aircraft. In the early stages of the Shuttle several missions were failures, and several fishing vessels were lost due to interception by the German Navy, but after having received the three submarine chasers, there were no more losses.

The Bergen born, Leif Larsen, nicknamed Shetlands Larsen, was the Norwegian leader of the Shetland Bus and was perhaps the most famous of the Shetland Bus heroes. Larsen became commander of the Norwegian submarine chaser Vigra with the rank of Sub-Lieutenant. In total he made 52 tours to Norway in fishing vessels and submarine chasers. Larsen became the most highly decorated Allied naval officer of the Second World War.

At the conclusion of WW2, the Nortraship fleet of Norwegian free ships, were progressively returned to the original owners together with war reparations to cover their lost tonnage. Once again Norway has now become one of the world’s major maritime nations.

The Norwegian Submarine Chaser Hitra (above) now preserved, seen at Bergen in July 2022.

Above is an image of Leif Larsen’s boat used during the failed operation to attack the Tirpitz, typical of those craft used in the Shetland Bus campaign.

As alluded to earlier, the Norwegian contribution to the Allied war effort at sea is often afforded little recognition, but it is an historical fact that deserves the fullest and highest acknowledgement and praise.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item