1974/75

By Sandy Kinghorn

The second world war cost Blue Star Line 29 ships out of a prewar total of 38. Ships can be replaced but people cannot and the loss of 646 lives made the owning Vestey family so saddened and disheartened after the war that they decided to give up shipping altogether. Only Ronald Vestey, then aged 47, realised that Britain desperately needed to rebuild her merchant fleet and that Britain’s national finances were in a parlous state, so Ronald persuaded the family to start again. Four 65 passenger cargo liners replaced the four lost twin-funnel ships for the London east coast of South America service and new liners for the Australasian trade were put in hand – very similar to their prewar predecessors with six cargo hatches each.

The second world war cost Blue Star Line 29 ships out of a prewar total of 38. Ships can be replaced but people cannot and the loss of 646 lives made the owning Vestey family so saddened and disheartened after the war that they decided to give up shipping altogether. Only Ronald Vestey, then aged 47, realised that Britain desperately needed to rebuild her merchant fleet and that Britain’s national finances were in a parlous state, so Ronald persuaded the family to start again. Four 65 passenger cargo liners replaced the four lost twin-funnel ships for the London east coast of South America service and new liners for the Australasian trade were put in hand – very similar to their prewar predecessors with six cargo hatches each.

Then, in 1950, four new seven-hatch liners were ordered, two with Pametrada steam turbine single screw propulsion, two with twin screw Doxford diesels. At that time engineering discussion raged about Steam v Diesel. Both had their advantages and disadvantages but it was the enormous price rise of fuel oil in 1973/74 which sounded steam’s death knell as steamers burn much more fuel oil than motorships.

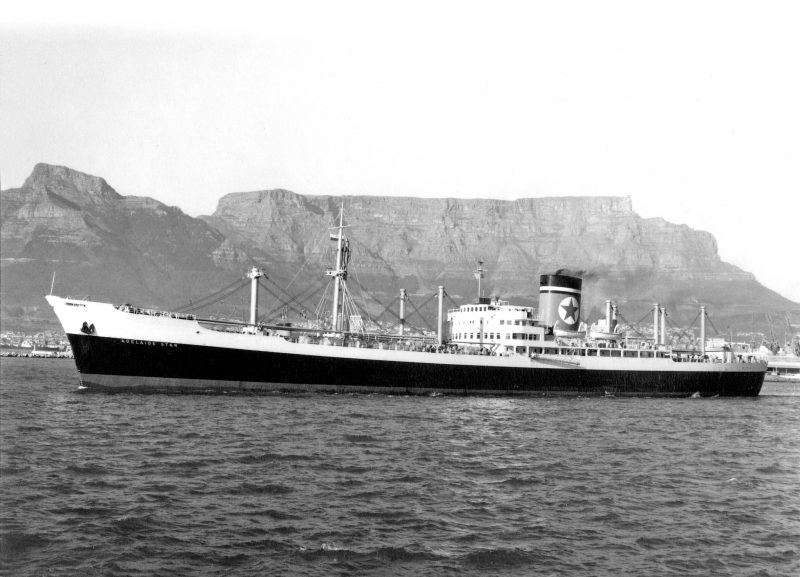

They were four splendid ships, each with first class accommodation for 12 passengers. The two steamers, Tasmania and Auckland Stars were built by Cammell Laird at Birkenhead while the two motorships Wellington and Adelaide Stars were built by John Brown at Clydebank. Adelaide Star when built had the world’s largest refrigerated cargo carrying capacity.

I joined her as captain in Liverpool on 21st October 1974. Her cargo for New Zealand had been booked by that famous old Liverpool shipping firm, Gracie Beasley, whose office contained vast amounts of old sailing ship material which had been used in making that well known TV Series – The Onedin Line. Next day Mr Beasley took me out to lunch at his club. When crossing the Pacific did I ever call at Pitcairn Island? he asked over the pudding. It seemed most of his captains would go nowhere near Pitcairn, as though fearing a Fletcher Christian in his crew might take over the ship there! When I said I always called to meet my old Pitcaim friends he beamed and said he had six cases of Churchill Centenary postage stamps which had to get there for the old boy’s hundredth anniversary and no other ships would take them. When I said I would consider myself honoured to take them he poured me another drink and drove me back to the ship.

We were to sail next day. That evening a handwritten message was pushed under my door stating that a bomb had been placed on board, timed to go off when we let go our last mooring rope.

What to do? To search a fully laden ship would have taken days, so I hoped it was just a note from some sailor’s girlfriend who didn’t want him to sail, and decided to sail on time. Our departure pilot was an old friend and of course I told him about the bomb threat and as we pulled off our berth there was a loud bang.

“There’s your bomb Sandy,” he said but it was only one of Mr Doxford’s engines telling me it didn’t want to sail either. Our engineers fixed it in a couple of hours and off we went with a full cargo and six passengers.

One of these was a retired doctor who had served in the RAMC during the first World War. He told me that one night in the trenches he saw one of our lads, wounded, crawling towards our line, so he went out to help him in. As he stood up a sniper’s bullet caught him in the back and he fell. Regaining consciousness he struggled to where he thought his own lines were, then saw the plough constellation in the night sky and realised he was going the wrong way, towards German lines.

Ever since he had raised his hat to the Plough, as he had been when I first saw him. He still had that German sniper’s bullet in his back. It kept him warm, so he said.

At the Panama Canal we were told the new locks then building would be completed by 2014, one hundred years after the canal first opened. That in 2016 they are not yet completed just goes to show that most building work takes longer than first anticipated. The new locks will enable bigger ships to use the canal faster.

Approaching Pitcairn I was asked by radio if our doctor could come ashore to see two patients about whom the resident nurse was worried. Taken ashore in one of the island longboats, our doctor examined both ladies. Elderly Vi Me Coy was sadly too ill to move, but 13 year old Yvonne Brown had a grumbling appendicitis and, with her father, was brought in our ship to Auckland, where her operation went well.

At Auckland Purvis Young and his wife and daughter came down to invite our doctor and me to a meal at their house in the suburb of Henderson, where many Pitcairners now live. They laid on a sumptuous Pitcairn party after which there was singing and music and I was asked if I would call at Pitcairn on our way home. So of course I did, and using a ten ton derrick picked up six longboats with thirteen islanders to take them to the uninhabited island of Henderson, 107 miles up the road.

Not only would they collect miro wood there, to make their models, but of course enjoy a few days holiday. They would then sail their longboats home, laden with the miro wood which had almost become extinct on Pitcairn. We had taken them with their longboata aboard on a fine night with smooth sea, and we would be off Henderson about seven next morning. Purvis Young, now back on Pitcairn, was in charge of the party. Purvis slept the night on my dayroom settee and his twelve lads cheerfully dossed down in the lounge. To my concern when I looked out next daybreak I saw grey sky and sea, rising white capped swell, not suitable or safe for launching longboats Taking Purvis a cup of tea I expressed my concern – all those large boats and thirteen men, unable to get off. Purvis looked out over the sea and boomed, “Before we sailed with you we prayed, asking the Lord for fine weather. He never lets us down.”

An hour later we arrived off Henderson – fine, sunny weather, blue calm sea, only a light swell – no problem.

Henderson itself is a low, rocky island, without water but in whose caves are skeletons of shipwrecked sailors from long ago. One voyage I had taken several Pitcairners to carry out a funeral of a recently found family who must have been here many years. All that remained were four skeletons lying neatly at the cave entrance and a man and a woman inside the cave round what must have been a fire and the skeleton of an unborn baby. They must have been here for years and probably died of starvation. The men of an American Navy ship set up a white cross outside the cave, still visible from the sea when last I passed that way. Another cave had a pit dug in the sandy floor in which were several skeletons, without heads!

In New Zealand we loaded a full cargo of frozen lamb and bales of wool at Auckland, Timaru and Bluff for Liverpool.

By the time we reached Panama our twenty five year old Doxfords were protesting their age. White metal had started running out of the main bearings.

At bunkering port Curacao three days later we spent nine days alongside while our engineers toiled nobly to put things right. The local ship repair yard did not know how to do it! On the way to Liverpool our fresh water ran out so by the time we arrived we all smelled less than sweet. The owners decided that, as this type of ship was unsuitable for containers, she was now obsolete and we would take her to Masan in South Korea to be broken up.

Returning from my leave I found our new third mate was a middle aged alcoholic. When I tried to have him replaced I was told no third mates were available.

“You’re only going for scrap. He can’t do much damage … ” For this delivery run, out via Cape Town, our crew was reduced from 64 to 32. All signed on on sailing day morning and of course I was asked if I would give them a sub, cash, “For our wives of course”.

The Seamens Union rep. was with me at the time and after I had said I would give all who wanted it ten pounds and paid this out against signatures The Union Man an old friend said rather cynically – “That’s the last you’ll see of that lot”.

But to his surprise they were all onboard sober and ready to go at sailing time.

Outward bound I managed to keep third mate more or less sober but I kept his 8-12 watch with him, just in case. At Cape Town we took fresh water and some fresh vegetables and I learned that our third mate had got drunk and accosted a white lady, to be arrested by a big policeman. Two of our engineers had been following and told the policeman, “We’ll take him back to the ship officer. He won’t cause any more trouble.” They did and put him to bed to sleep it off.

But on the next 8-12 night watch he was still drunk and berated me aggressively for telling him off. “Who was I to criticise an officer?”and he made no attempts to fix the ship’s position by taking bearings of the land. So next morning I put the ship into Port Elizabeth anchorage, paid him off and sent him home at his own expense. At home of course he took it up with officer’s union. Said he’d been wrongfully dismissed. But the union knew him of old and his case got no further.

Before he left the ship he promised me he would go and see my wife. But I told him we had two big alsatians who did not take kindly to visitors.

So I kept the 8-12 watches to Masan which made an interesting change.

Sunda Strait between Sumatra and Java took us close to Krakatoa, still smouldering but which in 1883 had erupted twice, so violently that their explosions were heard over 3,000 miles away in Australia and spectacular sunsets appeared round the world for months. At least 36,000 people died as a result and huge waves cast ships ashore over half a mile inland.

The South China Sea is a dangerous place. One part, south of Latitude 12 degrees north is considered too dangerous for shipping and is called the Danger Ground. Careful navigation and ship handling is of the essence – I was glad our third mate was no longer with us!

Going up the long inlet to Masan I asked the pilot if many ships were broken up here. “Oh yes Captain, we now have three!” My last ship graveyard had been Kaohsiung, Taiwan, with the Caledonia Star in 1971, where there were dozens!

Customs boarded here and immediately said I must pay duty on all the alcoholic drink in our storeroom. As this would have amounted to several hundred pounds I asked the agent, Mr Moon, what I should do?

Mr Moon the Agent here had been born in Japan where the Japs had taken his parents to act as slave labour during the war. Near Hiroshima, where, in the school playground one fine morning he and his playmates saw a huge white flash in the northern sky. The first atom bomb. He said the best thing to do was to give all the storeroom’s contents away before the Customs returned next day. So each crew member came up, delightedly surprised to be given a bottle or two, ‘Present for your father.’

At Liverpool I had told the purser how to do the crew wages. He was new to the purser’s job but seemed keen and able. Occasionally during the voyage I asked him how he was getting on. “Fine, no probs”, was his reply. But when we got to our hotel in Masan and I asked him for the papers as I had to radio our London head office with exact figures of money to bring down to Heathrow to pay the lads off, I found all he had done was write each man’s name at the top of his payslip and nothing else. He assured me that his girlfriend in Liverpool would do it all for him, when he got home!

So I spent all that night in the hotel and half the flight home working all the wages out.

Of course the lads had sampled the contents of Dad’s bottle and the airport manager read me the regulation stating that no member of a party attempting to join a plane under the influence of drink or drugs would be allowed. But I think he soon came to think that he’d be better off without this lot, and when we were walking to our plane over the tarmac an elderly engineer collapsed onto the ground and I called for a doctor, the manager turned round and left us to it. We got him aboard with difficulty but on his feet. After takeoff the lads thought a singsong was called for and I eventually completed the accounts and got them sent off to the gentle strains of Cats On The Rooftops.

Touching down at Anchorage, Alaska for bunkers, we were taken into the office a very prim and proper B.O.A.C. lady reprimanded me sternly. Passengers had complained that my crew were drunk. I apologised and promised they would be sober all the way to London (Dad’s drink had long gone by now.) I apologised again and the lads all apologised and we promised to be good boys henceforth. She was not amused.

Waiting in the departure lounge a new hostess, blonde and beautiful, carrying an arm-full of papers found that the door out was not of the self opening kind. Seeing this Alex Gemmell, a wee sailor from Glasgow, ever ready to use his fists, leapt to his feet and opened the door for her, bowing deeply as she smilingly sailed out to the plane.

After we had taken off over the snow I was told by a steward that the Captain wished to see me on the flight deck, and took me up. I was sure I was going to have those ‘Drunks’ regulations read to me again. But to my surprise the Captain, a tall immaculate white shirted New Zealander greeted me warmly, asked how I was finding the flight. When I said “Interesting,” he laughed and said he was sure.

Thereafter we chatted freely. No mention of Regulations. The lads were mostly asleep by now anyway. This splendid Captain told me that of course he could not take drink on duty, but was sure I could do with one, and had me shown into the first class bar where the lovely blonde hostess poured me a huge lowland whisky.

“Captain”, she breathed, “I think your crew are wonderful”.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item