Cabin Boy to Captain – Part Three

By Robert Wyatt

His next ship was the S.V. James Craig that was held up in the harbour waiting to sign on a crew. David signed on in 1920 as ordinary seaman.

After David joined her she sailed to Newcastle, N.S.W. to load a cargo of coal for Hobart Tasmania. During the voyage south the ship struck westerly gales, and started taking on water and she was forced to return to Sydney for dry docking. The crew were paid off, the voyage lasted 10 days.

Rothesay Bay

There were still plenty of positions available in sailing ships, but it was a different matter for places on the expanding steam ship fleets. David was able to join the S.V. Rothesay Bay, then berthed in Sydney in March 1920 as a senior ordinary seaman, at 17 years old.

The ship was on a regular run between Newcastle N.S.W. and Wellington, New Zealand with farm produce. However to David’s dismay, the ship lost that contract to a steamship. In 1920 sailing ships were regularly being put out of commission and the newer faster steamships took over voyages usually reserved for sailing ships. So the Rothesay Bay loaded sand ballast in Newcastle harbour for her voyage to Hobart where the ship was sold and the crew were paid off.

Cardinia

David paid his own passage, ironically by steamship, to return to Sydney, and then to Newcastle to join the S.V. Cardinia.

David signed on as an able seaman. Cardinia was to to load coal for Auckland, New Zealand. The crew were all young and consisted of 4 boys (cadets), 2 ordinary seamen, 12 able seamen with 3 officers, 21 in total. It was a quick trip to Auckland in fine weather and after discharging her cargo of coal, she took on ballast of clay and sailed to Levuka, Fiji to load a full cargo of copra for England and European ports. David was looking forward to returning to England for the first time in 14 years, as well as working with such a young crew in a sailing ship with the Cardina’s particular type of rigging. It made him feel like the veteran. The relaxed atmosphere onboard was once again in stark contrast to the S.S. Moira and her crew with their vigorous views.

Cardinia sailed from Fiji fully loaded, and set her course to the north of that island group that comprised the colony. The charts of that area were notoriously inaccurate, with only rudimentary soundings marked. It would be another thirty years and a world war before complete surveys of the reefs around these islands were completed. It was hazardous sailing especially at night. There was no information on what currents there were in their area so the officers had every right to be concerned with a fully laden ship on a lee shore.

On the third night at sea and in the middle watch, the ship suddenly shuddered, and then took on a slight list to port. This brought the master on deck in a hurry. Cardinia seemed to be aground. His anguish was indescribable. However it was decided to wait for daylight to make a proper assessment of the situation, in case they could float her off at the next high tide. In the meantime the bilges were sounded, and if further evidence was needed of the ships predicament, water was found in the midship bilge soundings.

Daylight revealed the ship high and dry on a uncharted reef with the tide still falling. In the distance a small island, also not charted, along with the reef they had come to grief on. The Master ordered their long boat lowered, and with the mate were rowed out to get a clearer picture of their situation, and what were their chances of floating her off at the next high tide. One glance was enough, Cardinia had broken her back when the tide had receded and left her balanced on the reef with a full cargo.

The next important task was to take steps for the survival of the crew. The small island in the distance seemed a logical place to make a camp until they could be rescued. Working parties were organised to strip the ship of all food and water containers, then as much timber and firewood as they could collect. The sails were to be used as shelters from the frequent tropical showers, and the sun during the day. After three days of non stop work, they had established their camp on the island. Cardinia looked forlorn perched on the reef, until the next cyclone would see her become part of the reef that had claimed her.

It was quite a shock to discover that their little island was a haven for sea snakes that came ashore in the evenings to breed. It was fortunate that none of the crew were bitten, as they couldn’t have done very much with their limited medical equipment and training. By keeping fires alight at night the snakes kept their distance, it also alerted any other ships in their vicinity that they needed to be rescued.

They were eventually rescued by a cutter from Suva, where the authorities had been informed by a passing steamer, which was unable to get closer to their location. Repatriation to Sydney was by the Union Company’s steamer S.S. Niagara as D.B.S. (distressed British seamen). All they had left after the ship wreck was what they stood up in. This meant another shopping day for David with his mother Isabella.

In 1922, competition for work in the steamships was still fierce, however there was one advantage of being registered as a D.B.S. as David took precedence over other sailors, and was allowed first refusal for crew placings at the maritime employment office.

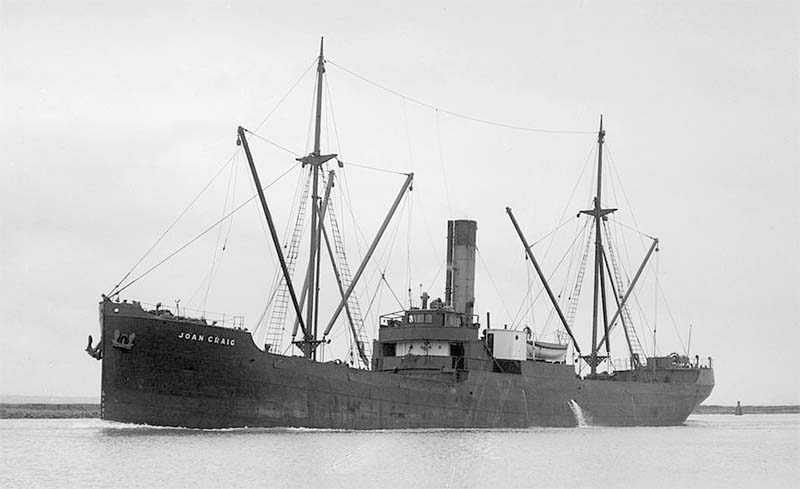

Joan Craig

The position of his choice was Able Seaman on the S.S. Joan Craig.

The Joan Craig was owned by RS. Lamb and Company, a subsidiary of J.J. Craig of Auckland, New Zealand. who also owned a fleet of barques. The ship was engaged in the general cargo trade between Australian East coast ports and the New Zealand west coast ports.

After 6 months as A.B. on the Joan Craig David was rated as Leading Seaman, or Bosun. After his stay in hospital in Brisbane, and the introspection during his recovery, coupled with the near disaster on the Cardinia, if the shipping industry was to be his life, then it was important to secure his future in this industry. The only answer he could see was to take the examination for Second Mates Foreign Going certificate. What happened after that, providing he passed, would be up to him.

As an A.B. on board the Cardinia, David had been invited to join the cadets in their navigational studies, the use of the sextant, and the azimuth mirror, and was surprised that the maths subjects they were to learn were below what he had been taught at his high school. That was worth bearing in mind for the future.

In early 1923, after serving as bosun on the Joan Craig for twelve months, the company granted him a period of unpaid leave to study for and then sit for the Second Mates exams in Sydney, providing he had accumulated sufficient sea time. After submitting his papers to the Department of shipping in Sydney and it being confirmed that they were in order, he was invited to take up the next vacancy to sit for the exam in five weeks time.

In his favour was the study time afforded him onboard the Joan Craig, as well as the targeted tutoring provided by that ships officers, usually in their own leisure time.

The five weeks seemed to vanish and then it was time to report to the exam rooms, ready or not. Any misgivings he may have had about his ability to cope with the other two exams for mate, and master quickly changed when he received the blue form confirming a pass. Now he had to find a job, and in this J.J. Craig was only too happy to employ him as third officer on the Joan Craig, the ship he had served on as A.B. and Bosun.

David now took that confidence into his preparation for the chief officers certificate, which he obtained in 1925, and again for his masters Foreign Going certificate, with sail endorsement in 1927, at the remarkably young age of 24 years.

He had started his climb up the ranks, and with due diligence and a large amount of good fortune he could look forward to becoming a master in charge of a foreign going vessel.

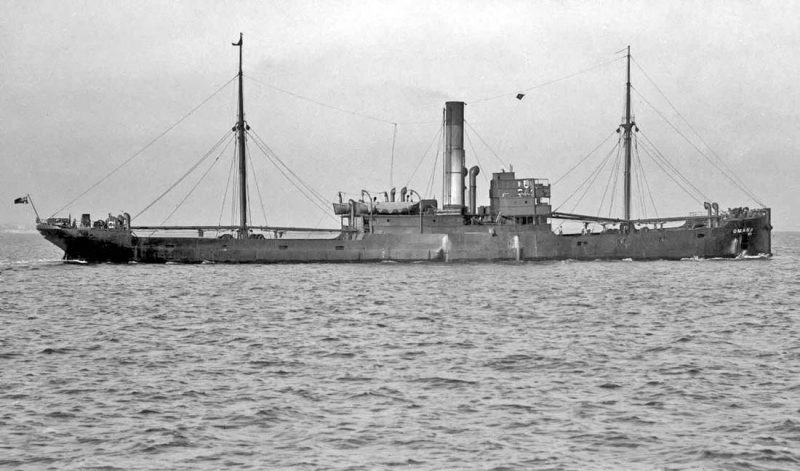

Omana

J.J. Craig’s ship Omana was charted to R.S. Lamb Shipowners and used as a collier on a regular run from Greymouth on the South Island of New Zealand to Auckland on the North Island, with coal from the mines at Greymouth.

In Greymouth Harbour, 1928 and the usual bleak winters day, Omana had just finished loading her cargo of coal, the deck crew were trimming the cargo, before covering the hatches, in preparation for sailing. The 3rd officer Munro was on deck, keeping an eye on the crew at work, but able to look out over the mist shrouded harbour. Still partially obscured by the mist, another ship was entering the tiny harbour. From the funnel colours, she was another of R.S. Lamb’s fleet and as she approached the town wharf David noticed she had an obvious list to port, and her deck cargo of timber packs were a shambles, as a result of severe weather. After berthing several crew members were seen to be stretchered off the ship. The rumour mill on the Omana, part of life at sea, went into overdrive. The new arrival was the S.S. Kalingo.

The local Lamb’s agent in Greymouth, who hardly ever visited the Omana, was now onboard and in earnest consultation with Omana’s Master. The story unfolded later in the Master’s cabin of the Omana.

The Kalingo had hit very bad weather on a voyage from Wellington to Newcastle and her cargo of timber packs had shifted. Worse still, both the second and third mates had been injured in their efforts to secure the deck cargo which had broken loose.

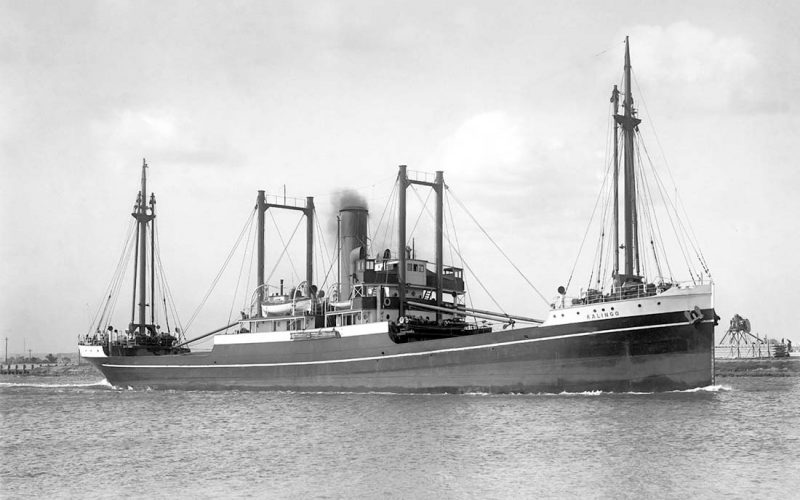

Kalingo

The instructions relayed by the agent to the Omana’s master from Lamb’s office in Wellington, was that 3rd officer David Munro was to leave the Omana immediately, and join the Kalingo as acting 2nd officer for the interrupted voyage to Newcastle and before leaving port sort out the cargo problems so that the ship was seaworthy. This would leave the Omana with only two watch keeping officers until she reached Auckland to discharge her cargo.

It sounded simple until David had the hatch covers removed on Kalingo.

Looking into the holds he was appalled at what he saw. All the “dont’s” in cargo stowage he had learned the hard way on the Wathara 9 years ago were in front of his eyes. Leading by example he climbed into the hold, and with Kalingo’s A.S. following, began the task of re-stowing the cargo and righting the ship.

The work could only be done during daylight hours as there was no hold illumination available and the wharf lights were poor and made worse by the weather. Firstly the holds had to be emptied of their cargo, one at a time, then re-stowed so that they formed a solid block and not move with the motion of the vessel. This re-stowing also provided space in the holds where the deck cargo could now fit, and not be at the mercy of the weather. In so doing this would provide more stability for the ship, as she may have been overly ‘tender’ before.This may have contributed to her problem with the weather.

Fresh bread on ships in those far off days was but a memory. It was ship’s biscuits, usually full of weevils, or nothing. These were only digestible when dunked in water, which in itself was often undrinkable. Therefore the smell of newly baked bread drifting from a small bakery near the wharf was too much to resist for 2nd officer Munro. He walked over to the bakery during the fifteen minute break he allowed the crew every two hours and bought several newly baked loaves which he shared with the crew on his return. In appreciation the crew seemed to work harder resulting in him becoming a regular client of the shop. During these visits he was able to establish a rapport with one of the young ladies behind the counter. This friendship blossomed over time, especially when David returned to the Omana as Second Mate then Chief Officer on the regular run to Auckland.

Captain David Munro and the young lady, Helen Sharp, were eventually married in Sydney on the 31st July 1928.

After seven days of hard continuous work, the Kalingo was once more ready for sea, with her cargo stowed securely and without the list, also with the deck cargo now in the holds. At sailing time the local Lamb’s agent visited the ship with a message from his head office. It was, “well done and hearty praise for those involved”. On reflection later David admitted to being a little dismissive of these compliments from the head office as for him it was all in a days work, doing a job he was trained to do and being paid for it. He was far more interested in his new friendship with Helen from the bakery shop.

It was much later in his life when he was able to read some of his fitness reports the Union Company held, that he realised what an advantage he had gained with people who would control his future promotions within the company. His name and reputation was then in front of senior management, and this would serve him well for many years, even after he had left the sea.

On the 19th February 1930, the ships and office buildings of the R.S. Lamb and Company were purchased outright, by the Union Steamship Company of New Zealand. This sent shock waves through the serving officers of R.S. Lamb. Would they be re-employed by the new owners? What about their seniority, in such a large company? Would they have to start from the junior ranks again? As the situation evolved R.S. Lamb’s officers had every right to be concerned for their future because in the initial purchase negotiations, the Union company management advised Lambs that they had sufficient officers in reserve to crew the three extra ships.

It was only after strong representations from the R.S. Lamb directors in their letter of 6th February 1930, sent personally to the Chairman of the Union Steamship Company, that they relented and agreed to take two officers only. This was to be subject to the union companies mandatory eye test held in Sydney which all officers employed by that company had to take every year. Failure in any part of the day long test meant immediate dismissal from the company, without any recourse.

In 1930 David Munro was still serving as acting second officer on the Omana and being recently married, was relieved to receive his letter of appointment to the Union Company and still have a job at sea. His eye test was the unknown factor. However he need not have worried as he passed this on the 10th April 1930, without any qualifications, or re-testing ordered. His transfer to the Union Company’s sea going staff was on the 16th April 1930. The only headache was that with the new company he was likely to be New Zealand based.

The 1930s had another reason to be remembered by him quite apart from joining the Union Company. The hurricane that was the world wide depression in the northern hemisphere began to be felt in Australia and with it, New Zealand. The shipping industry was particularly hard hit with ships being tied up and crews laid off. David was one of them when the Omana reached Sydney. The company could only keep those ships that were viable at sea, and crew them with the older officers, at only 26 years of age he was not one of them.

While the break was welcome after almost 18 months continuous sea duty and four hour watches, with increasing unionised crews, and shipboard food. He could relax while revelling in his wife’s cooking, and get to know his son, Arthur, born on the 29th September 1929 while he was at sea. However hanging over his head all the time, was how was he going to provide a living for his family, if the shipping industry, which was all he knew, remained depressed, already his meagre savings were almost exhausted.

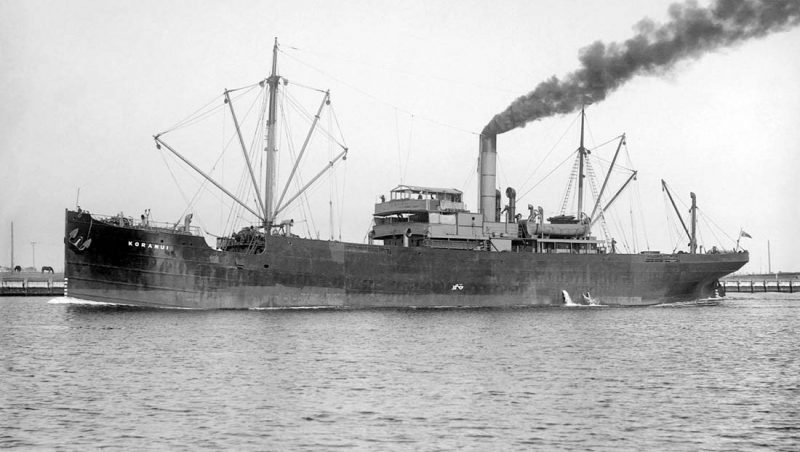

Koranui

After only three weeks at home, a telegram from the company, a surprise in itself, instructed him to join the S.S. Koranui, at present loading in Sydney, as third officer. This sudden recall to duty turned out to be more cargo stowage concerns on that ship, which had delayed her sailing from Sydney. It also justified his reputation as the go to person for the safe and practical stowage of general cargo.

On the 10th June 1930 David rejoined the Omana as the chief officer when the ship was put back into service after the worst of the depression appeared to have passed for the shipping industry.

For the next six and a half years David Munro served as second officer and then chief officer on the Kalingo and the Gabriella.

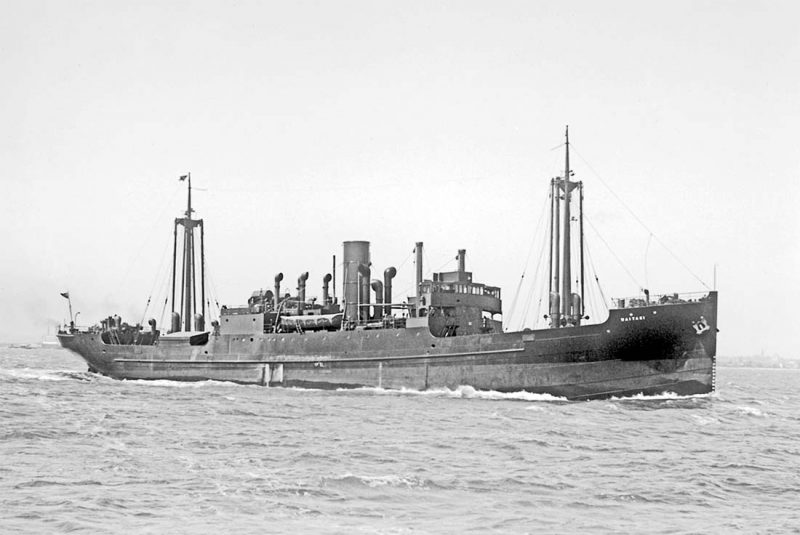

Waitaki

On the 12th October 1936, he received his letter of appointment as Master of the Union Company ship Waitaki.

The Waitaki was alongside the company’s Wellington wharves undergoing conversion work on her holds for her new role sailing to ports in the South Pacific. Captain Munro’s brief on taking command, was to oversee that the work was being carried out according to the company’s specifications then take the ship to sea to verify that the completed modifications did not compromise sea worthiness. Finally, he had to sign off for the work on behalf of the company. He was also to remain onboard while the cargo was being loaded to ensure that it met the safety standards required by the company. Although he was loath to admit it, this was the result of the successful reloading of the Kalingo seven and a half years ago in Greymouth harbour. He may have forgotten about it over time, but the company obviously hadn’t and had noted his reputation as a successful officer, who was able to “make ships work”.

To complete the requirements for command of Union Company’s vessels, he had to sail with the senior masters in the company, as second chief officer to pass his exemptions for five New Zealand ports, then take the obligatory eye test in Sydney. Once these requirements were in place, he was to take over the command of the Gabriella, replacing that master who was on the point of retirement.

The year 1936 saw war clouds gather in Europe again. England was forced by events, to commence limited rearmament, starting with the Royal Navy. During the depression, government cut backs on that service had meant a lot of warships had been scrapped or mothballed, but now these ships were being hurriedly brought back into commission. Dockyards were also busy building new ships to replace the ones scrapped. When the cutbacks started to bite, many naval officers were out of a job. These officers in the main sought positions with English Shipping companies to retain their sea time and experience.

Now the Royal Navy wanted them back as soon as they could return to a U.K. port. Many English shipping companies were caught out and would have trouble keeping their ships at sea without qualified watch keeping officers. The obvious remedy was to draw senior officers with master’s tickets from their subsidiary companies to fill these gaps.

The Union Steamship Company had been part of the P&O Group since 1917. It was only natural that they would have to part with some of their senior masters, to the P&O group of companies. The initial requirement was for six officers to transfer to the P&O company to then be placed in ships throughout the various lines. General cargo experience was one skill sought after when the selections were being made. As usual the rumour mill aboard the company’s ships was active. Captain David Munro knew from this that he would most likely be one of those six officers and he also knew that some English Shipping Companies were on two year articles. This meant he could be away from Australia and his wife and young family for up to two years and if war broke out while he was away he may be away for a lot longer, or he may not get home at all. His worst fears were realised when he was asked to renew his passport.

B.H.P.

The Year 1937 and Captain Munro was home on leave in Sydney after completing his five pilot exemptions successfully and awaiting the results of his latest eye tests, but with the thought of the possible transfer hanging over his head, he later confessed this to be the worst time in his life. The lighter moments were getting to know his two children, and appreciating home life away from the stresses of command. A telegram, an unusual event, when it wasn’t from the company, asking him to phone a person from the giant Australian company, B.H.P Company Ltd. That done, an appointment made for the following day, to discuss a possible position in that companies maritime division.

The interview with senior members of the staff selection office lasted all morning. It left him in no doubt that his reputation as a responsible and highly trained cargo officer had preceded him to that company. At the end of the interview David was made an offer to join that company as a cargo supervisor with the choice of one of three locations, Newcastle, Port Kembla or Whyalla in South Australia. He took the offer of more time to discuss the position with their company with his wife Helen.

The important points of the job offer were that firstly, if he accepted the job the family would have to relocate to Newcastle. The other two locations were out of the question. Secondly, the wages for the position were not what he would have expected as a master in command. Could they live on them and bring up a family? Thirdly, if he accepted the position any hope of a command at sea, something he had hoped to achieve for the last twelve years would most probably be gone, possibly for ever.

On the credit side, he could forget about the overseas transfer and the turmoil in Europe, and become a husband and father on a day to day basis. With these tumultuous thoughts he spent a restless night. In the end the final decision was his and he accepted the B.H.P. Company’s offer for the position at their Newcastle works.

Before changing jobs he had to relieve the chief officer on the S.S. Kalingo loading in Newcastle, and his letter of resignation to the Union Steamship Company, dated the 31st March 1937 was sent to the company from that ship.

The rearmament in England also caused changes to be made in Australia’s young manufacturing industries. Rearmament took steel that the U.K. produced in large quantities, converting it into domestic products for export. Now, most of that steel went for the U.K.’s own use and the flood of those products after the depression rapidly changed to just a trickle.

The Australian Government, alarmed at these developments, began prodding the country’s only steel producer, the B.H.P Company Ltd., to consider building factories near their steel plants to make a start to rectify this short fall, to make the country independent in the long term, with the eventual aim to seek export markets in the region.

Up to this point most of B.H.P.’s shipping had been engaged in the bulk shipments of coke, coal, iron ore and limestone from ports around the country’s coastline. The people selected by the company to supervise these shipments did not need any specialist skills in cargo handling. The ships arrived at their loader empty, and when required tonnage was in the ship, she sailed. B.H.P. was considered an engineering based conglomerate, so those working in the shipping side had been employed in supervisory rolls in that company’s main business interests. Cargo stowage was therefore relegated as a specialist occupation. With the influx of steel products now ready for shipment, the company management recognised they would need to employ experienced people to staff their newly formed stevedoring companies. Otherwise they stood to lose ships at sea because of cargo shifting, or ships damaged so badly that lives could be lost due to negligence on the company’s part.

Captain David Munro was one of three specialist cargo supervisors appointed by the B.H.P. Group in 1937. His choice of Newcastle, which was the largest of the three ports, meant his expertise in his field gained over 19 years was put to immediate use to shift the backlog of products on the company’s wharves. In time he was able to move his family to a home in the relatively new suburb of Stockton, just across the Hunter River which formed the port of Newcastle, from the steel plant and its wharves.

Captain Munro’s fears about war breaking out in Europe in 1939 were realised, as were his fears of not returning from the conflict if he had accepted the transfer to the P&O Group. He was shocked to learn much later that five of the six masters who had accepted the transfer became war casualties. However he did not escape the war entirely after Japan’s entry into the conflict, the war came to him.

As the conflict came closer to Australia more cargo needed to be moved and Captain Munro’s work load increased accordingly. In his position he became very friendly with masters and officers of other ships owned or under charter to the company. He was appalled to learn of their loss when their ships were sunk by submarines, from both axis powers operating off the coast.

The first loss was the B.H.P. ship S.S. Iron Chieftan on 3rd June 1942, followed by the B.H.P. ship S.S. Iron Crown on 4th June 1942. Another B.H.P. Ship, S.S. lron Knight was lost on 8th February 1943.

He was particularly upset when he heard of the loss of one of the Union Company’s ships, the Kalingo, on which he had served in all three capacities. The Kalingo was torpedoed and sunk by the Japanese submarine I-21, 100 miles due east of Sydney which she had just left on the 18th January 1943. She was on a passage to New Plymouth, fully loaded and sank very quickly, but fortunately with the loss of only two lives. The remainder of the crew took to the lifeboats but were prevented from sending a distress radio signal due to the equipment being damaged by the explosion. The authorities in Sydney were amazed when Kalingo’s lifeboats rowed through the Sydney Heads the next day without anybody being aware of the sinking.

In Newcastle on 9th June 1942, it was a cold wintery day when dawn and dusk seemed to meet half way. The wind off the Hunter River brought with it light rain. All wharves had ships alongside, and Captain Munro working the evening shift, 4pm until midnight and was fully occupied keeping the cargo moving into the ships and avoiding any delays, that would upset their sailing times, and clog the wharves for more ships that were waiting to load. The wharf labourers working the winches on the ships envied their companions working down in the holds, away from the cold wind and drizzle. The entire Newcastle district was on high alert after the midget submarine attack on ships in Sydney harbour the previous night, followed by one of the mother submarines peppering that cites eastern suburbs with shells from her deck gun.

At about 9pm that evening the somewhat normal evening shift changed in an instant to something far from normal. From the black river flowing past the moored ships, five huge water spouts in quick succession leapt from the surface of the river, spraying those on the decks of the ships with cold river water. They were under attack from a Japanese submarine lying just off Stockton beach which was trying to hit the huge gasometers at the steel works. Fortunately the submarines captain aim was “off” otherwise the resulting conflagration would have devastated the entire steel works and its dormitory suburbs. As it was eight shells landed in the suburb of Parnell Park near the front gate of the steel works, causing little damage and no casualties. After the war a Japanese officer on the submarine I-21 commented that they had intended to keep firing until they found the range but they were put off by a lucky near miss from one of the coastal guns, who firing over open sights in the darkness nearly scored a hit on their submarine. The submarine having failed in its attempt to cause major damage to the port, went looking for further targets in the shipping lanes around the east coast, and as a result sank three more ships before returning to her base in the Truck Island chain.

On that fateful night the B.H.P. Company’s wharves were all lit up for the evening shift and when the shooting started, nobody could find the switches to turn the lights out, thus providing a perfect aiming point for the submarine. Eventually the wharves were plunged into darkness, just in time for the all clear siren.

For the next 39 months until the war moved away from Australian waters and towards the Japanese homeland, more steel products with a greater variety were being produced at the works keeping Captain Munro looking after more ships who would spend less time in port so they would clear the wharves for the next ship. Quality time at home was now a luxury and was to continue to be so into the late 1950s.

Captain Munro was appointed supervisor of the Port Waratah Stevedoring in 1964 after the retirement of its incumbent. At the B.H.P. Company’s maximum retiring age of 62 years on April 1965, it was his turn to begin meaningful retirement, this after 47 years in the shipping industry, 20 of those spent at sea.

He was to be remembered by those in the industry as consistently approachable with a high work ethic and extensive practical experience in his field of general cargo stowage. He had no patience with loud bluster, arrogance or tactlessness in others, regardless of their position in the company. As a quiet achiever he left a lasting impression on those who followed in the position he had held with his impeccable record of safe and practicable cargo work.

Epilogue

On a hot summers day on the 21st February 1954, Captain David Munro stood on the B.H.P. Company’s steel loading wharf, watching the Australian United Steam Navigations ship S.S. Caloundra berth to load steel for Brisbane. His attention was on the freighter’s poop deck, where in a new ill fitting uniform and a little green with sea sickness, stood his nephew, on his first trip to sea as a deck apprentice.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item