Cabin Boy to Captain – Part One

By Robert Wyatt

Preface

Captain David Munro was born in Aberdeen, Scotland on the 30th May 1903 and lived a full and productive life of 89 years before crossing the bar on the 8th October 1992.

During his lifetime he experienced two world wars and several smaller ones that claimed the lives of some 80 million people. He witnessed a worldwide depression and a flu pandemic. He survived serious illness, a shipwreck and Japanese coastal incursions.

He served his time ‘before the mast’, starting as a 14 year old cabin boy on a sailing ship witnessing the quantum changes that occurred within the shipping industry of which he was part of for 47 years which unfortunately was to include the beginnings of the Maritime Union involvement.

In his tenure at the B.H.P. Company Ltd. Newcastle, (N.S.W. subsidiary) as an assistant cargo superintendent, then superintendent, he was regarded as a ‘hands on professional’ that left big shoes to fill on his retirement.

He was my mentor during my sea- going days, a person to look up to knowing that when he was there you were in safe hands. My life has been a little richer in having known him. His saying, “a mistake is not a mistake until you make it a second time” still resonates with me today even after 70 years.

I am proud to say he was my uncle.

Robert Wyatt

Gold Coast, Australia

April 2017

A Dedicated Life: The Captain David Munro Story

July 1945 – Winter in Australia! In the city of Newcastle, New South Wales, a cold overcast day with an early morning fog, made worse by the smoke from the local steel mills and its dormitory factories.

Newcastle was a coal mining and steel producing centre and in the fourth year of the Pacific War against Japan its port formed by the Hunter River was crowded with ships loading or unloading. Some were being repaired after battle damage or being built at the State Dockyards slipways further along the river.

Without a bridge across the Hunter River, the Northern suburb of Stockton was serviced by a small ferry and a larger punt for vehicles, both giving access for its citizens to the commercial centre of Newcastle and its rail link to the state capital of Sydney.

On this cold winter’s day most passengers on the early mornings Stockton ferry headed for the small cabin to escape the chilling breeze blowing in from the river. By contrast, Captain David Munro on his way to work at the B.H.P.

Up against the cold he chose the open fore deck of the ferry in order to see the maritime mosaic of the port, as the ferry made its way across the river.

After the ferry headed away from the small pontoon that served as a wharf, the first to come into view were the coal loaders (the usual clouds of coal dust around them!) with ships underneath loading. In the middle distance the State Dockyards, with ships of all sizes, easily identified by the cacophony of sound from the riveters and the blue flashes from the welders, just visible through the haze. An acrid smell and voluminous red-brown smoke distinguished the B.H.P.’s steel works much further along the river. The blast furnace towers were just visible over the dockyards floating dock.

Uncle and nephew’s viewing was suddenly blocked as the ferry passed close under the stern of a small freighter heading up river. The uncle’s steadying hand on his nephew’s shoulders, a support against the extravagant motion of the ferry as it crossed the freighters broad wake. The same steadying hand would be there in later years.

The short trip across the river ended at the town wharf with the passengers climbing the still wet and slippery stairs reach to the roadway leading to the city centre or to the rail station with the Sydney bound express train.

The uncle, Captain David Munro was well versed in maritime matters. Having been a Master Mariner in both sail and steam from the very early age of 24 years, a feat without parallel even today. He also had an enviable reputation as an assistant cargo supervisor at the B.H.P. Newcastle Works.

His father, Arthur Munro, was born in Scotland in 1887 and had also gone to sea at an early age but in a very different capacity as a marine stoker. This role was to change again with the introduction of small steam engines in some of the newer sailing vessels. These engines provided some momentum when the vessel was becalmed or manoeuvring in a harbour without tugs. He was rated as a donkey man with responsibilities for these engines but formed part of the deck crew when the ship was under sail only.

Some Scottish shipyards in the early 1900s were building small colliers for Australian owners. These new ships had these engines installed and they were of a larger type than those often found in sailing ships of that era.

Arthur Munro was employed by these yards to crew these new ships for their prospective owners in Australia and then train their employees as to their operation and maintenance.

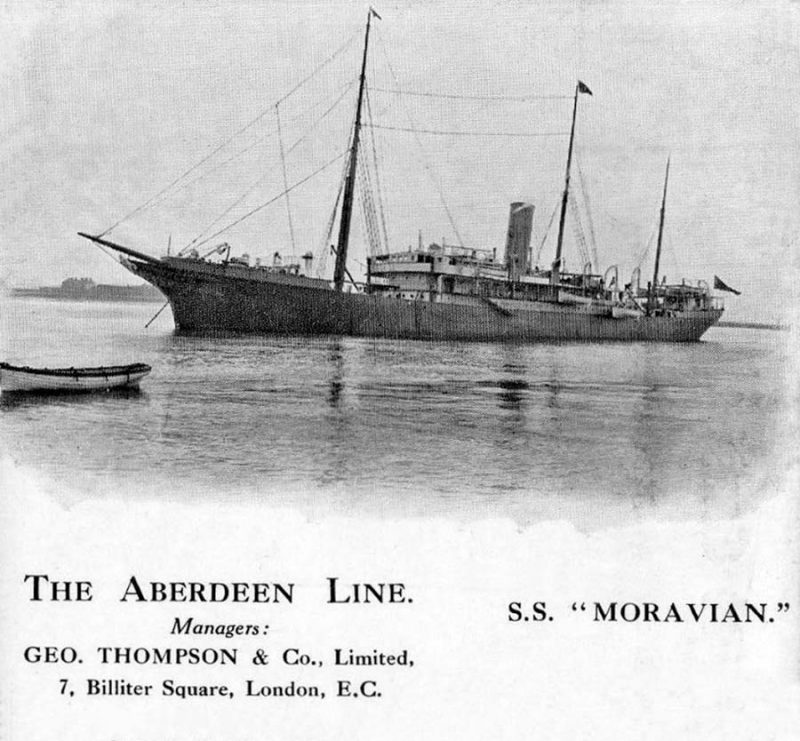

The promise of a more stable employment in a new country with a healthier environment convinced Arthur to bring his wife Isabella and their four children out to Australia in 1910 on board the S.S. Moravian.

As war clouds gathered in Europe in 1912 the U.K., shipyards reverted to building ships for the rapidly expanding Royal Navy. Arthur’s position then became redundant and he was forced to seek what work was available locally, which was landscape gardening at a suburban hospital. The pay was meagre even by the standards of that time and the family struggled to make ends meet.

Even this casual work came to an end in 1917 as wounded soldiers returning from the war in Europe were given priority as part of their rehabilitation.

Arthur Munro had little option but to return to sea as a donkey-man/stoker in the New South Wales Maritime Services steam tenders servicing their depots and lighthouses around that state’s coastline.

He was still working in this position for the Maritime Services and was on board a steam lighthouse supply tender when he contracted peritonitis and died at sea in 1926, aged 59 years.

David Munro, after emigrating to Sydney Australia, with his mother Isabella and his two other brothers and his sister found his early school years in Sydney challenging, due to his broad Scottish accent and strict upbringing.

However, he overcame these difficulties and was considered a very good student eventually earning a place in Sydney’s prestigious Fort Street Boys High School, a school for high achievers in the “the three Rs”.

The First World War caused financial stress to many families in the country. The Munro family was no exception and was the cause of David having to leave the Fort School at 13 years of age, his scholastic achievements notwithstanding, and look for a job to help the family put food on the table. John his elder brother found work in a milk supply company and David became a junior clerk in the State Timber Yard. This position didn’t last very long as the yard was incorporated into the Commonwealth Department of Defence where employment was restricted to those over the age of 16 years and prepared to enter the armed services to help fill the high mortality rate being experienced in Europe in 1916.

A position as a junior clerk for a Sydney solicitor followed and convinced David ultimately that, with his limited education, a law career was out of the question unless he could afford to return to school, matriculate, and then enter university for five years to complete a law degree.

There were very little employment opportunities open and he was approaching the age when choices for a career would be decided for him with a call up into the Army or the Royal Australian Navy. Neither of these services appealed to him, especially with the almost daily release of the hideous casualty figures from the war in Europe. Adding to his dilemma, his older brother John had already been called up and was now training with the Territorials. This was a locally formed brigade whose job was to guard vital installations against possible sabotage by members of the Central Powers. It appeared to David that John seemed to spend his time in the Brigade, marching up and down then cleaning ancient artillery pieces. This was something not worth thinking about until he had no other options open to him.

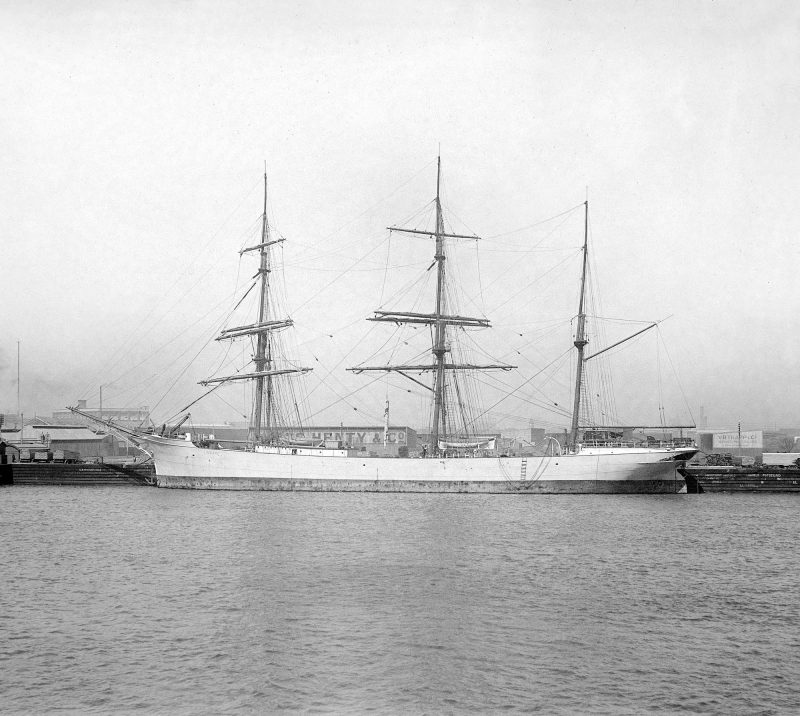

On his brief time off from the solicitors’ office and to stay out of the house with its never ending chores, David usually walked down to the Sydney wharves enjoying the sea air and to clear his mind of the crushing monotony of the clerical work. There was always something to see in the forest of masts of sailing ships loading or unloading their cargo. Walking down the long wharf, dodging horse-drawn wagons and small hand trucks, he saw at the end of the wharf and the last in line of the moored ships, a small three-masted vessel, a barque, which moved against the wharf under the influence of the tide and the stiff breeze.

David stood and watched the activity on board as bags of potatoes, tins of flour and sides of meat were carried up the narrow gangplank. The name Wathara was painted on the stern. She was a lovely little ship even to David’s inexperienced eyes. Standing on the edge of the wharf trying to make sense of all the activity on board he noticed one of the crew was watching him from behind the gangplank. The crew member called out to David and asked him if he would like to come onboard and have a closer look at the ship? The offer was eagerly accepted and David joined those on the gangplank. Once on deck the crew member who had invited him onboard suggested he walk around the deck, being mindful of the many hazards that lay about waiting to be secured.

After about an hour on board David found the same crew member, firstly to thank him and then, apprehensively, asked how did one get a job on a ship such as this one.

Expecting the terse reply that only experienced seamen and mature males could be considered for positions on a sailing ship, he was speechless with the answer that he could join as a Cabin Boy. Furthermore, there was a position on the Wathara for immediate start on voyages to New Zealand. The only requirement would be a letter from a parent or guardian allowing him to join the ship and accept the Master’s authority.

David left the ship with a lot to think about. This could be a turning point in his life. If only he could convince his mother to allow him to join this ship and go to sea on a vessel which she had never seen or knew anything about. Then there was the letter he needed to join the ship. Who could he get to write such a letter? It would have to be someone from outside the family who had those skills.

It was the Mate of the Wathara who had invited him onboard and as he watched David hurry back along the wharf felt he had seen the last of him. Then he returned to his duties to get Wathara ready to go to sea.

The advantages of going to sea as a career were not lost on David. It was just that he had not thought of it before. Firstly, he could escape the boredom of a dead-end job where he could see no future for himself and also he would also not be subject to the heavy handed discipline from an irascible father. Probably the most important reason in this time of war with its compulsory military service was that he couldn’t be called up when he turned 16 because the Merchant Navy was exempt from the call up as it was considered an essential service.

After arriving at the Munro household in inner Sydney David, with typical boyish exuberance, blurted out his idea of going to sea as a cabin boy on a sailing ship. He expected an explosion from his mother and he wasn’t disappointed.

His mother, Isabella Munro, was a feisty Scotswoman who believed life was meant to be hard and any deviation from this mindset was viewed with suspicion. However, she was also a realist. After she had time to reflect on her son’s bombshell, she saw some benefits in the idea of him going to sea.

If she refused to provide the letter he wouldn’t be accepted by the Master of the ship and would remain at home until he was called up for military service. He could very likely end up a casualty or worse and she would lose him just the same without having any say in the outcome. If, on the other hand, she relented and provided the letter she felt one trip away might cure him of the urge to go to sea and convince him of how good he had it at home and to settle down in the family for the foreseeable future. A further benefit also occurred to her. With both older boys away, John on guard duty and David at sea, the house would be much quieter. Both these boys were now standing up to their father Arthur and this had resulted in some serious clashes of late.

Reaching a decision which she hoped would turn out to be the right one, David was to ask his employer at the law firm (Mr. O’Brien a solicitor,) to prepare a letter which she could sign giving her consent for her son to join the ship as a cabin boy. At the same time he would have to advise his employer that he would not be returning to the law practice.

His fellow workers at the practice were openly amazed and also very scornful of his decision to leave the relative safety and security ashore and risk it all by going to sea on a sailing ship. Later on in life David was to learn that most of the young clerks at that practice who had sneered at his choice of occupation would be conscripted into the army and would not survive the war!

Later that day the Mate of the Wathara was astonished when David returned to the ship and handed him the letter duly signed by his mother allowing her son to join the ship. The Master’s reaction was more official.

David was to be signed on and shown where he berthed in the forecastle. At that point he had to be told what he would need onboard and to say goodbye to his family as the ship had completed her cargo work and supplied the stores for the next voyage. She would sail the next day, weather permitting.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item