There is a romantic sound about the name Robin Hood’s Bay and having arrived there by that long steep road which runs sharply down to the sea from the Yorkshire moors, one’s preconceived ideas of the place are not disappointed, for there is a genuine air of antiquity and simplicity about it, with none of the “Ye Olde” touch which so often spoils places striving to attract visitors. Robin Hood’s Bay is old enough not to bother about such gimmicks.

A steep little road,with a gradient of something like one in four winds down to the sea from the car park at the cliff top, with attractive little alleys branching off it. There is hardly a house in those alleys that is not several hundred years old, and their age seems to sit on them lightly. There is nothing uniform about “the Bay” for every inch of space has been utilised and everyone seems to have squeezed as much ashe could into his little bit of ground.

In the old days when Britain’s coasting trade was carried mostly in sailing vessels, Robin Hood’s Bay was more important than it is today for, although ships did not actually go there (there is no possibility of a harbour), very many were owned there and seamen from there manned them. Those days are gone long since and of all the men who knew them there are only a few still left living in “the Bay”. One of them is

Captain Thomas Jackson, born there in 1877, who is one of the few men still with us who sailed in one of the old Collier Brigs.

Captain Jackson lives in “TheBolts”, one of those attractive alleyways running off the steep little hill which ends at the waters edge. The house opposite his has the date 1709 on it. His house is a little more modern, 1729, and looking at the stonework of those houses, now over 250 years old, one is amazed at the freshness of it. Time and the winters of more than two centuries seem to have left them untouched.

Captain Jackson’s father was a farmer and the family have lived in the area for many years. There was no particular seafaring tradition in it, but it is certain that living in Robin Hood’s Bay for so long many Jacksons must have been seamen. When young Thomas expressed a desire to go to sea, two uncles connected with the fishing industry wanted him to go to Grimsby and become a fisherman. But his father decreed otherwise. “No” he said. If you want to be a sailor you’d better do it properly”. So in 1892 young Jackson was apprenticed to Captain George Milburn for five years in the Brig Danube.

Captain Milburn, who had been at sea himself, owned at this time the Danube and another brig the Sir Henry Havelock. Earlier,in the seventies, he had owned a larger vessel, the barque Warspite, built at Whitby in 1854.

The Danube and the Havelock were practically sister ships, just over 200 tons gross with dimensions 92x24x14, which gave them about 3.8 beams to length, tubby little craft. The Danube, oak built and copper fastened was built at Whitby in 1855.

Captain Jackson joined the Danube at West Hartlepool where she was loading for Rochester.

A fine picture of the Danube, painted in 1896 by an artist called S. Middleton, and now hanging in Captain Jackson’s sitting room, shows her to be almost straight stemmed, with double topsails, single topgallants, and royals. There is a little artists licence here, for actually the brig, like most of her type, had no fore royal, only a main royal. She is shown with reef points on her upper topsails and these were sometimes used, but the courses were never reefed. In the painting the bentnick boom she had on her foresail is clearly shown. The bentnick boom was a spar fitted to the foot of the foresail for ease in going about in narrow waters,and was standard equipment in collier brigs. It made for handiness in working in narrow waters as there were no tacks or sheets to attend to,and also saved a man. It was a common place fitting in the whalers, for working in ice.

The painting (above) also shows the Danube with a small boat hanging over the stern and another on the main hatch.

The master of the Danube was Capt. William Harrison, who had a share in the vessel. He was a Robin Hood’s Bay man whose family, like the Jacksons,had lived in the district for many generations. In winter Capt. Harrison stayed at home and let his mate, by the name of Reekie, have the ship, a very convenient arrangement! It may be said that neither Capt. Harrison nor his mate had a certificate. A few years before this there were two Harrisons in Robin Hood’s Bay who were ship owners, John who owned the snow Vivid and M.Harrison who had the brigs Arica and Lucy.

Although many ships were owned in Robin Hood’s Bay, there were no less than 108 in the early 1870s, it was not a port of registry, but Capt. Jackson can remember seeing, among other ships, the Margaret Nixon, the Nio the Roseand the Coraline, all with the words “of Robin Hood’s Bay – port of Whitby” across their stern under the name. The Margaret Nixon was a snow, Nio and Rose were brigs and the Coraline was a brigantine, all of them owned at one time by Capt. Isaac Mills, who was later a master in Turnbull Scotts steamers.

It should be made clear that the Danube had been a coaster all her life and had never “been foreign”. During the years when Capt. Jackson sailed in her she invariably loaded coal in either West Hartlepool or Sunderland, never the Tyne. There were four apprentices and two sailors besides the captain and mate, a total crew of eight.

The apprentices and sailors lived in the fo’c’sle below decks right forward and they slept in hammocks not bunks. One of the apprentices had to do the cooking, and this was a job no one minded, as it meant they could dodge a good deal of the work and keep warm. The meat was always salt beef, never salt pork, presumably beef was cheaper than pork. Generally speaking the food was not bad aboard the Danube, undoubtedly much better than onboard deepwater sailing ships

The cargoes were discharged at various ports in the south of England, Shoreham, Rochester, Dover, Gillingham, Ramsgate and the means of discharge was by a dolly winch and “Armstrong’s Patent”. Sometimes the brig went back up north ballasted with chalk which was discharged at Hilton, above the bridge over the Wear at Sunderland, but sometimes she was lucky and was able to get a cargo of cement from Rochester for use in the construction of the new piers at Sunderland and Roker. When loaded with cement she was never put down to her marks for fear of straining her too much.

Hanging in Capt. Jacksons sitting room is a photo of the Robin Hood’s Bay lifeboat Ephraim and Hannah Fox being launched on 18th November 1893, still spoken of in the Bay as “the Great November Gale”. The Danube, with young Jackson onboard had just come out of Ramsgate on the Saturday, bound north in chalk ballast, when that historic gale struck her. The next day she found herself down nearly on top of Cape Griznez, under bare poles, probably having driven over the Goodwins without ever knowing it. After that they kept plugging away, with little idea of their position, until the following Thursday, when they caught a glimpse of Start Point through the driving rain, they had been driven two hundred miles down channel. They managed to work their way back up to Yarmouth Roads and lay there for a fortnight, amid a great fleet of ships all sheltering from the dreaded north east wind. The colliers never carried over much food and by the time they got to Yarmouth the Danube was completely out of stores and had to get some from ashore. By some mischance no report was sent to Robin Hood’s Bay of the brigs arrival and by the time she arrived at her loading port she had just about been given up for lost by her owner and relatives of the crew. This was the fate of another Robin Hood’s Bay vessel, the brig James and Eleanor,commanded by Capt. Philip Beedle which was lost with all hands somewhere between Lowestoft and Orford Ness in that same great gale.

The Danube was nearly forty years old when Capt. Jackson joined her and it was a routine job to pump her out night and morning. About half way through his apprenticeship she was drydocked at Boghall drydock in Whitby, the copper bolts were taken out and replaced by galvanised iron ones and it was commonly said at the time,that the price of those copper bolts paid for the docking.

Having completed his apprenticeship, Capt. Jackson had to put in a short spell in steam to enable him to sit his second mate’s certificate.

This he did in the 1,934grt Annie a steamer bullt in Whitby in 1879 and owned by Rowland and Marwood of that port. The master was Capt. Thornton and the mate was Thomas Granger of Robin Hood’s Bay, later a master in the company. The steward of the Annie was the father of the mate and one sees here a most unusual case of demotion, the steward had been master, probably uncertified, of a little Whitby brig and when this position was no longer available to him, he went steward on the ship on which his son was mate.

When Capt. Jackson was in Rowland and Marwood’s ships the company had nothing but steamers but back in 1878, before the company had been formed, T. Marwood & Son of Whitby had a fleet of six ships, two of them steamers. They had the Quebec built ship Mandarin and the barque Prince Waldemar, the Sunderland built barque Tycoon and the snow Eupatoria, this latter probably a Black Sea trader. But it is significant that by 1883 they had abandoned sail altogether and had three steamers although Christopher Marwood of Whitby had seven sailing ships, all but one of them brigs, an indication of the popularity of the brig rig as long as it could hold it’s own with steam. But, as soon as economy became vitally necessary, the brig was doomed.

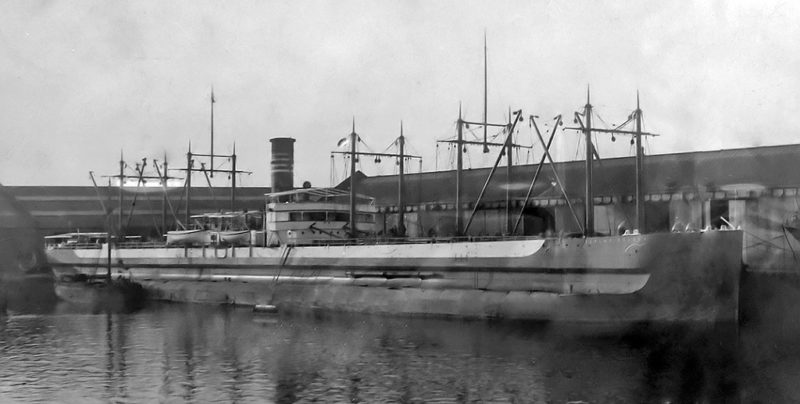

After leaving Rowland and Marwoods, Capt. Jackson was with the well known London firm of Bolton & Co. in their steamer Raphael (above). When the ship was sold to Chile in 1906 he could have gone with her but, as it meant being away from home for three years, he turned down the offer. He could have also moved to another of Bolton’s ships chartered on the Australian coast but turned that down for the same reason. After that he saw service in a variety of ships and his experiences show how chance or luck plays a part in all our lives.

For a time he was mate of the steamer Lowlands, owned by Leonard Macarthy of Newcastle. She was an old ship, built in 1888, and must have been built on economical lines for there was no power to the windlass, the power for heaving up the anchor was transmitted to it by a messenger from the winch at number one hatch, an almost laughably primative arrangement and one that used to be seen occasionally down in the Mediterranean on old Greek and Turkish ships.

While in the Lowlands there occurred an alarming incident. They were bound down the London river and the captain, a rather nervous old man, had kept the mate on the bridge with him until they got to the Sea Reach. Capt. Jackson had just gone down to his room when he heard the anchor running out with an almighty roar, in some way it had become released with the ship going full speed and with the tide under her stern. By a seeming miracle the chain did not part, but the windlass was smashed, and they were left lying there with a full scope of chain out and no windlass to heave it in. The anchor was eventually hove up by a messenger, but it was a painfully slow job.

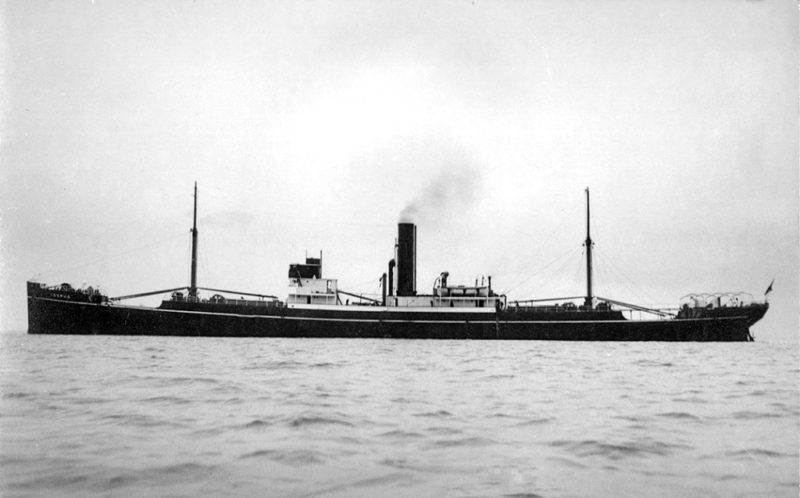

After the Lowlands Capt. Jackson was mate of the Elmsgarth (above), which had been built in 1896 as the Jaunita North for that grand old company Nitrate Producers Steamship Company. Two years were spent in the Elmsgarth partly chartered on the Indian coast running coal from Calcutta, a hard trade for a ship with European crew, for they never took kindly to coasting in the tropics.

Capt. Jackson’s Masters Certificate was issued at Cardiff in 1902. After that Capt. Jackson spent some years with Runcimans, a period which spanned the First World War. Here again, it was strange how luck enters our lives for, although he was constantly in the war zone and had narrow escapes from torpedoes, he was never in a ship that was struck, whereas other men were torpedoed several times. On one occasion in convoy a torpedo intended for his ship just missed her and struck the next vessel the Pennyworth. On another occasion in the Exmoor, the London pilot on the bridge actually saw the U-boat’s periscope and it was the fact of her being so close that saved them, the two torpedoes going under the ship.

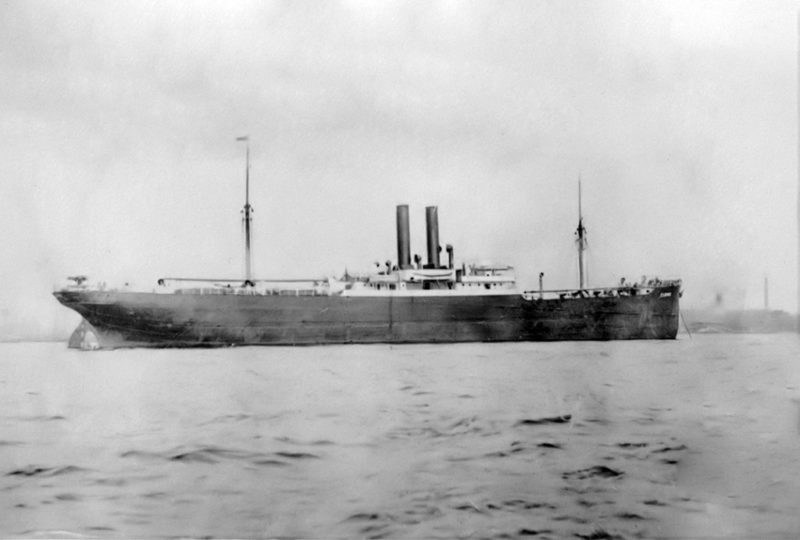

Soon after the First World War Capt. Jackson was for a time mate of the ex-German steamer Elbing (above), a two funnelled vessel built in 1898 for the Deutsche Australische Dampfschiffs Gesellschaft of Hamburg. But by 1921, world trade was in a bad way and Runcimans started selling off their ships so, again, it was a case of finding a new job.

Capt. Jackson then joined the Western Counties S.S. Company and sailed in the Inchmead, which had been Runciman’s Inchmoor, and was chartered to the Italian Government.

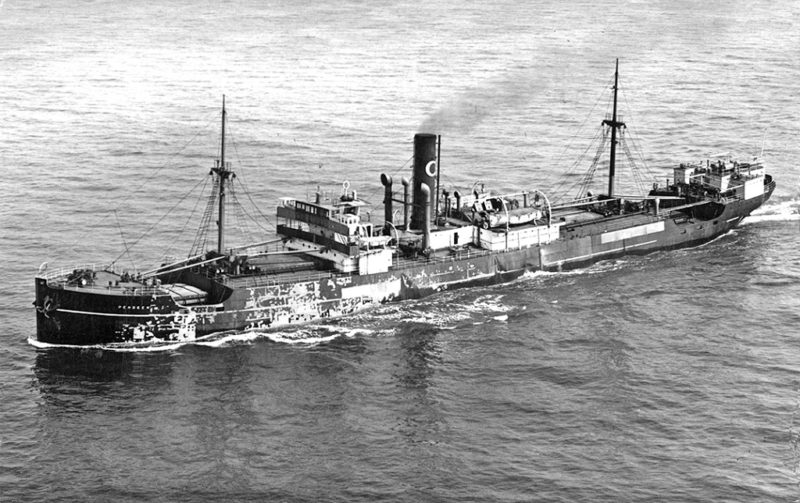

Then command came in the new ship Cedrus of 4,094grt (above), a ship owned by Howard Tennens of the Arbor S.S. Company, and for some years Capt. Jackson was in the Australian trade. But then the owner died and his ships sold. Cedrus was sold to Buries Markes.

The great depression was upon the world and Capt. Jackson stayed at home through those years before eventually returning to sea as mate of the London Greek Panos in which he spent three years, part of it trading between the USA, River Plate and North Africa.

When the Second World War started he was already a man of 62 but remained at sea all throughout the war, much of it spent in the Chellow steamer Pendeen (above). There again he was lucky and, although constantly in dangerous waters, he escaped the torpedoes and bombs which took such a toll on allied shipping.

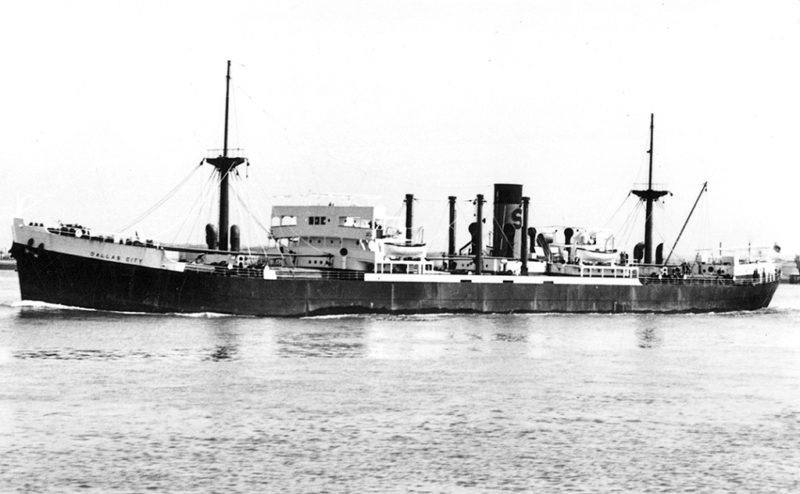

His last ship was the Dallas City (above), an 10,315 ton deadweight steamer owned by Sir William Reardon Smith, in which he served until 1948 when he was 71 years of age. After that he retired to Robin Hood’s Bay and has led an active life afterwards.

Capt. Jackson is known to have sailed in other ships not mentioned, these include the 5,387grt Poplar Branch of Nautilus SS Co. (above), built 1902 Wathfield, built 1904, Arranmoor built 1915, Ornus, built 1907, Ulmus built 1926, and Cape Colonna built 1889 and broken up in 1912, but that is another story! The changes which have taken place in the lifetime of Capt. Jackson are truly remarkable.

He went to sea in a little old collier brig, when such ships were still common enough to hardly claim a second glance and was still at sea when the fateful bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. The links connecting his life with earlier times are no less remarkable.

Some of the retired seamen he must have known as a child in the 1880s had been born before Nelson fell at Trafalgar and were already at sea when Waterloo was fought. Something of the time and its relativity are brought home when one thinks of these things.

Captain Jackson, was my Grandfather, he had a long retirement and died on Christmas Day 1969 at the age of 92. The cottages in Robin Hood’s Bay still stand, but are now 2nd homes or holiday lets and the reliance is on the tourist industry.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item