During the 1960-70s Hong Kong became the world leader for demolition and breaking of ships, with major shipbreaking facilities located at Junk Bay and later at Gin Drinkers Bay (where the container Terminals are now situated). Of course, Japan, Korea and Taiwan also had a share of the market, but they came nowhere close to the dominance of Hong Kong at that time. China was a bit slower off the mark, mainly due to the political unrest that prevailed and backlash of their ‘Cultural Revolution’. The reality was, not until the beginning of the 1980s did China fully open its door to the commercial world and really start to expand and become a major player in the field of ship demolition.

By the late 1970s Hong Kong had out played its prime position and the pendulum had swung in the direction of Taiwan and Mainland China. This was due in part for the never-ending need in Hong Kong for building and land reclamation. Shipbreaking had previously become an important industry in Hong Kong because the market for scrap was directly related to the building industry, which was very buoyant in Hong Kong during these years, where the demand for mild steel bars was already well upward of 20,000 tons per month. To meet this demand for steel it can easily be calculated the tonnage of vessels required to be in the process of demolition at any one time. In addition, there was an increasing demand in south-east Asian countries for mild steel rods and bars, which could only be met in part by Hong Kong at that time. The high value placed on waterside land suitable for development and reclamation in Hong Kong soon outstripped Hong Kong’s capacity, so demolition of ships became less practical and moved elsewhere.

Hence, Taiwan became the kingpin. In particular, the southern port of Kaohsiung quickly developed into a major base for the industry where vessels could be brought alongside makeshift berths, double and triple banked, then, cut down using relatively cheap semi-skilled labour. This was very environmentally unfriendly and dangerous work.

Kaohsiung soon became the World’s #1 graveyard for ships. However, with the increase in environmental awareness and the land supporting these makeshift waterfront enterprises becoming too valuable for demolition, by the late 1980s the mudflats of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh rose to prominence by offering even cheaper labour as well as less stringent environmental regulations and lower taxes. Therefore, Hong Kong as the original destination of choice for ships reaching the end of their economic life and destined for demolition soon faded out in favour of alternative locations within Asia. Eventually Kaohsiung eliminated its involvement as a major player in ship demolition, leaving the Asian market almost entirely to the PRC.

Nevertheless, through the 1980s, Hong Kong was still an active participant in the demolition market, particularly the areas of short-term ship financing in support of Sales and Purchase brokerage, both of which were vital elements for successful deals to be cut.

By the time mid-1980s came around my company which was based in Hong Kong, managed a number of ships. As a consequence we were very actively engaged in all elements of technical and commercial ship management, including such things as insurance, agency, cargo and chartering brokerage, Sales and Purchase, ship financing, crewing and marine operations. The result was that we were suitably connected within the maritime industry which paved the way to become even more involved in the shipbreaking sector. It was also a period of major changes within the shipping world, when shipowners were selling off or in some cases defaulting on ship mortgage commitments, mainly due to high fuel costs and rapid movement towards containerization. Many traditional owners of longstanding suddenly found their tonnage was no longer economic or competitive and sold their ships rapidly at the behest of accountants. The result was that many fledgling ship-owners who acquired these ships did not foresee the rapid changes and quickly became burdened with uneconomic tonnage, causing many financial institutions to repossess vessels over which they held security. This development in the shipping industry triggered contact from various major financial institutions seeking consultation on what could be done with vessels on which they were required to foreclose.

We learned details from financiers who had several foreclosed vessels anchored in Hong Kong and Singapore because of delinquency by owners in meeting various financial obligations. The financial institutions sought a ‘One Stop Shop’ solution in terms of technical and commercial management to assist them to overcome the dilemma. They ideally wanted a full package at a fixed monthly fee for Technical and Commercial ship management with such things as insurance, survey, repairs, crew recruitment and wages, brokerages, port dues and taxes, fuel and lubricants, stores etc., being additional, but invoiced to them at cost.

Under the proposed arrangement the institutions received an attractive fixed monthly management fee with the headache of becoming reluctant ship-owners in which they had no technical or commercial expertise, was eliminated. As owners they retained responsibility for standard operating costs of the ship whilst the ship manager had exclusivity over the vessel until such time as a buyer was arranged, or indeed the vessel went for demolition. This scenario assured a handsome monthly income to the ship manager who was also able to claim legitimate brokerage fees on all cargo, sale or demolition of the vessel, recognized as standard within the shipping industry. The nub was, it became a win/win situation.

This type of ‘One Stop Solution’ worked very satisfactorily, with the word getting about amongst the financial houses which lead to further enquiries by others seeking a similar arrangement, and which, over ensuing years became a major source of ongoing business.

During this time, it became obvious there was potential for us, as a smaller player, to become involved in the demolition market which was starting to really become established in Taiwan and the PRC (People’s Republic of China). It stood to reason, if, now having built a reasonable working relationship with various Banks through our ‘One Stop Shop’ management solutions, we could acquire tonnage built with good LDT and quality steel, usually European built, with the support of short-term financing, there was every chance of decent profits to be made all round.

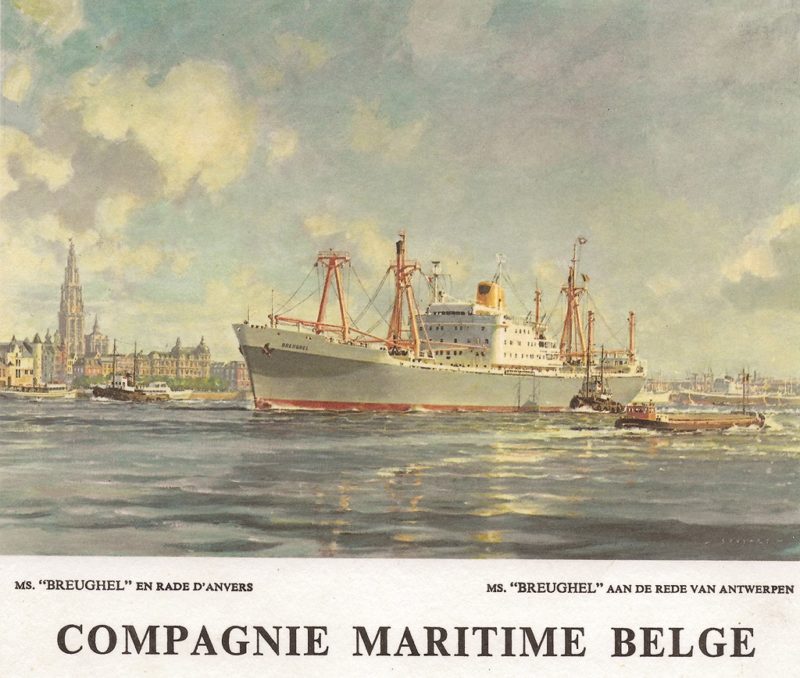

One such ship was the Treasury Alpha, formerly the Breughel of Cie. Maritime Belge which we took over in Singapore on behalf of one of the financial institutions. We renamed her Tamaki and traded around Asia for about one year before we arranged for her demolition at Qingdao.

We purchased three vessels of the Cap San Class operated by Hamburg-Sud on the N. Europe-South America service. They became known as the ‘White Swans of the South Atlantic’, due to their sleek design and high speed. We took delivery in Europe and working them towards Asia, booking various cargoes along the route. Eventually selling them for demolition.

The vessels purchased were Cap San Marco re-flagged and renamed Marco Polo, and Cap San Antonio re-flagged and renamed San Miguel. Both vessels were taken over in Europe and worked progressively in the direction of Asia, over the ensuing few months, until eventual arrival at the shipbreakers. The last of the trio purchased was the Cap San Diego. The Cap San Diego was built and launched by Deutsche Werft in 1961 for Hamburg Sud as the last of a series of six sister ships, but for her later years of service had been operated by the Spanish Shipping Company ‘Ybarra’.

I took delivery of this 9,859 dwt passenger cargo ship for our company in Barcelona, from the Spanish owners, where we changed her name and re-flagged her to the St.Vincent register. Our sole intention being to work the ship to the Far East, where we would sell her for scrap, as we had done with the previous two sister vessels. Her voyage to Asia was uneventful, where she arrived in Hong Kong some two months and several cargoes later, prior to meeting her intended demise in Taiwan.

This project, however, had an interesting twist, because the ship having arrived in S.E. Asia, pending imminent delivery to the breakers’ yard, received an eleventh hour reprieve. An offer was made by a Hamburg based ship conservancy group to purchase the vessel outright as she was, on the understanding we were to deliver her back to the new owners at Cuxhaven. Not wishing to see such a fine vessel go to the ‘Torch’ unnecessarily, the offer to purchase her and duly deliver her back to Germany was quickly accepted. Luckily for the buyers, our contract with the scrap yard had an ‘escape clause’. Hence, the ex-Cap San Diego was sailed back to Europe in ballast since the purchasers were paying all the voyage costs and required the vessel to be delivered as soon as practical.

The ship which we had renamed Sangria duly arrived at her designated delivery port, after which the vessel was reinstated to the German Register and sailed up the River Elbe to Hamburg with much pomp and ceremony with many dignitaries from the City of Hamburg onboard as guests, for the historic homecoming voyage. Soon after her arrival in Hamburg, the renamed Cap San Diego underwent a complete refurbishment to bring her back to her original splendour. She is now a museum and hotel ship at Hamburg. The rest I shall leave to history.

However, this wonderful ship remains, and is available for all to visit and enjoy. Several times a year, she hosts guests and embarks upon a trip along the Elbe. A crew of about 130 volunteers are required to keep her fully maintained and seaworthy.

In practice, acquiring a ship for demolition was a simple scheme. The way acquisition of suitable tonnage for demolition by scrap merchants worked was by a rate set within the demolition market based on a ship’s LDT. This allowed for a monetary scrap value to be easily ascertained for any given ship provided the LDT was known. LDT is “light displacement tonnage”, which is in simple terms the weight of water displaced by the ship, the mass of the ship excluding cargo, fuel, ballast, stores, passengers, crew, but with water in boilers to steaming level.

Ship Brokers involved in Sales and Purchase nominated suitable tonnage available on a regular basis. Brokers carefully matched their proposals as to the suitability of tonnage against our earlier defined criteria. One of our important requirements was that any vessels proposed to us for sale must still be in good trading condition and currently be in full Class with a minimum of 6 months remaining on all her Certificates. We were not interested in ships that had been in lay-up or out of service or Class for any period. Ships were subject to an initial inspection by one of our Engineering or Nautical team members to ascertain suitability to proceed from Europe towards the Far East under their own power, carrying cargoes along the route. All of which was a critical necessity in order to turn a decent profit, as previously mentioned. The economics did not make sense, for towing global distances for demolition.

Once a suitable ship had been identified, and the economics of the proposed exercise verified, we would attempt to obtain a short period of exclusivity with the Brokers pending our offer being put forward. In the meantime, our in-house team set to work sorting the short-term finances and seeking a Contract of Sale with one of our preferred shipbreakers as well as identifying suitable cargo. Once having become relatively well known in this sector of the industry matters tended to come together quite rapidly. Finally, a company surveyor would be dispatched to inspect the vessel’s condition and verification of vessel documentation and Class affairs, prior to our acceptance.

Broadly speaking, the important thing was to get a pro-forma Sales Contract in place for the vessel’s demolition with a wide Laycan (basically an agreed spread of dates between which the vessel may be delivered in accordance with contract), allowing us a reasonable scope for delivery to the scrapyard.

Once agreed in principal the financial backers knew a sale was imminent and the ship had been inspected and deemed suitable, together with viable cargo to cover costs of the delivery voyage, the short-term bridging finance soon fell into place and the deal was finalized. The Banks were comfortable as they held both the deeds to the vessel and were beneficiaries in the demolition contract, so their risk was substantially mitigated. Our profit derived from surplus remaining once the Banks had been paid out from proceeds of the sale. Depending on cargo revenues and modest gain on the sale price, overall net profit for the delivery voyage usually ranged between US$80-100,000, which on 1980 values was quite good for a short 3 months exercise. However, it was not always plain sailing and we did meet challenges along the way from time to time, which we managed to overcome. The completion of a successful voyage was not without risk to us. The secrets to a profitable enterprise lay in securing the right ship with reasonable revenue earning cargoes along the way, which was not always easy. It was a good year if we could achieve upward of 3-4 deliveries to the shipbreakers, excluding those ships we had under management on behalf of the financial institutions.

The actual delivery and acceptance of the vessel from the sellers varied according to what needed to be done. If it was usually prudent to change flag and name, this usually took a little longer but on average a vessel could be made ready for a demolition voyage within 10 days. This included crewing (we had our own delivery crew consisting of ship Master and senior Officers), Insurances, Bunkers and Lubes, fresh water, basic stores, victuals, arranging Radio Accounts together with the many other needs to make a vessel ready for a voyage following acquisition.

We conducted this type of exercise for several years, whilst scrap prices remained buoyant, during which we delivered a good number of vessels to Taiwan and China ship breakers. It was an interesting and exciting period, full of challenges. It yielded a great deal of satisfaction once a voyage had been successfully executed.

Typically, shipbreaking yards focus purely on economics, and expediency with little regard being given to the adverse effects on the environment caused by pollution. This always saddened me to see. At times, the ships awaiting their demise were banked up alongside the makeshift wharfs encroaching into the river, Kaohsiung being the worst example of all the demolition ports, from my experiences.

It must be said, there was a touch of the maverick doing this kind of business. One felt a little like ‘James Onedin’ of the ‘Onedin Line’ which was a popular TV series around the time. Take a risk, hold your breath and with professional management, hope for the best outcome. Fortunately, fate was good to us during the ‘Golden 80s’, an era now only living on through the mists of nostalgia, sadly never to be repeated.

However, by way of a bonus, the wonderful ship Cap San Diego remains, and is available for all to visit and enjoy.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item