Seafarers of the 1960s and early 1970s, serving on general cargo ships, are sure to have nostalgic memories of the East African Coast. Before the days of containerization and the introduction of container feeder vessels, it was common to call at a full range of East African Ports, topping up or delivering numerous parcels of cargo. Port stays could be short and others long by today’s standards.

My memories come rushing back to my Bank Line days, whilst serving as an apprentice on the Weybank (built 1945) and then the Levernbank (built 1961) during the 1960s. On both ships I regularly called at East African Ports.

For over 2 years I was employed on the Orient-Africa Liner Service on the Levernbank, a gem of a run, between Japan, Taiwan, Philippines, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Singapore and the full scope of East African Ports, basically ranging between Mombasa and Cape Town. This was a fast service for those days, the ship operating at 16 knots, when fuel was still relatively cheap, and it was economically viable to operate ships at their full design speeds.

Much of my sixteen months on the Weybank was spent doing a steady 11 knots, running between Calcutta, Madras, Colombo, Mombasa, Dar-es-Salaam, Beira and Lourenco Marques, commonly known within the company as the India-Africa Service.

My entire time trading along the East African coast is filled with exhilarating and graphic reminiscences, and a complete compendium of golden memories, while engaged on a great run, when ships were still ships, each with their individual character and trait.

At the major African Ports, such as Mombasa, Lourenco Marques, Durban, and Cape Town, it was not unusual to experience port stays exceeding one week, whilst at secondary ports it was generally limited to just a single day. At the other end of the spectrum, in India port stays could be up to six weeks in Calcutta, with Madras and Colombo, thankfully somewhat less.

In the Far East we also enjoyed good Port time but a better turnround was the norm. A month was spent coasting around Japan, typically several days each at such places as Nagasaki, Moji, Kobe, Osaka, Nagoya and Yokohama, always followed by a good 2 or 3 days at least in Hong Kong, Keelung, Kaohsiung, Bangkok, Singapore, and Port Swettenham, nowadays called Port Klang. Visits to Philippines or Borneo ports were somewhat shorter by comparison. We also made occasional calls at Mauritius and Reunion, in the Indian Ocean. On the Orient Africa Line, a round trip, say from Hong Kong back to Hong Kong was a tad over 3 months, as regular as clockwork. The run was so cherished, no one wished to leave the vessel and it was not unknown for some to volunteer and sign on for “double headers”. In my case I was particularly fortunate because my residence was in Hong Kong, so I could look forward to being home for a few days, at least every 3 months.

The term ‘East African Coast’ is generally used for the region between the River Rovuma which form the border between Mozambique and Tanzania in the south and the River Juba which marks the border between Kenya and Somalia in the north, spanning a distance of approximately 1,000 nautical miles.

The East African Coast included such ports as Kilwa, Zanzibar, Pemba, Mombasa, Mtwara, Malindi, Tanga, Ungwana and anchorages in the Lamu Archipelago (Manda, Shanga, Pate and Lamu). Of course, there were other tiny locations where ships just anchored or secured to a buoy, close to the coast and the various cargo was brought out by surf boats or barges. Then there was the Mozambique coast with its ports of Beira and Lourenco Marques, both with their strong Portuguese influence, not forgetting to mention the South African Natal coast, a little further south, featuring the delightful and beautiful port of Durban. These few ports warrant a story of their own, another day.

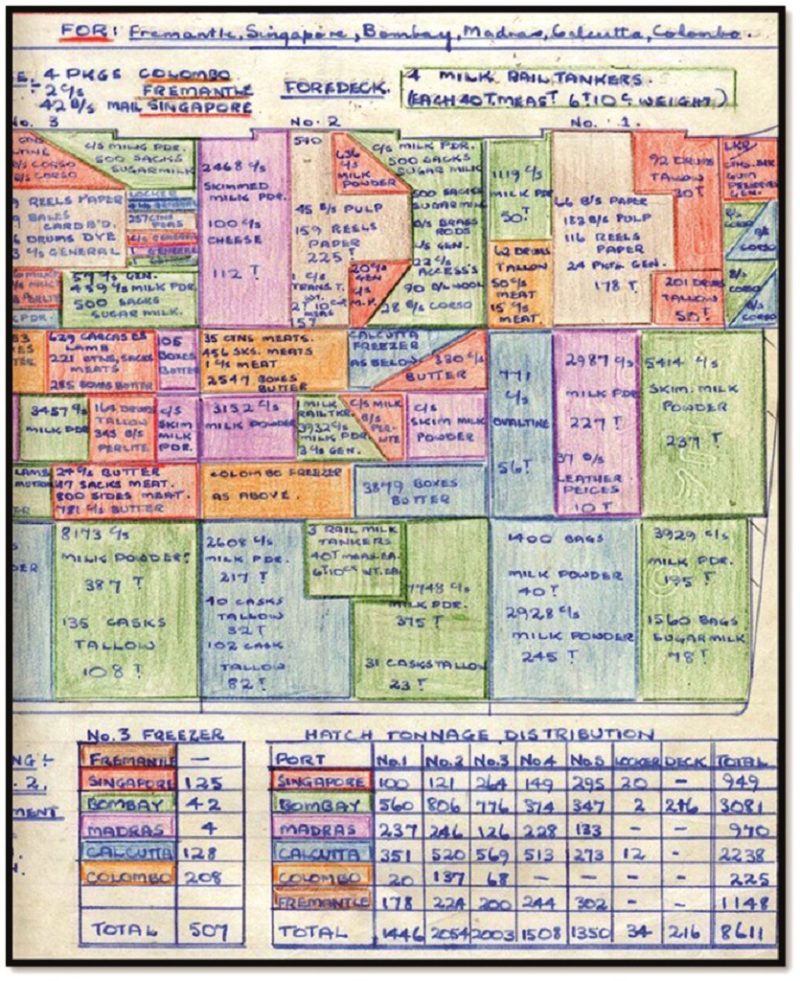

From personal memories, the East African Coast was always a favourite amongst ship’s crew, not only because of its stunning natural beauty, but also because of the friendly and hospitable nature of the native peoples. Not to mention the balmy and clement weather that the area enjoyed for a good portion of the year. It was often the case that a ship would depart one port at sunset, and be at the next at sunrise, all ready for cargo work to commence, so for the Deck Officers it could be a busy time, especially accommodating all the small parcels that typified the Liner Services provided by most owners of the era. Cargo plans, with their cascade of separations looking like a patchwork quilt, with all their colors and outlines depicting the various consignments. Not to forget the fragrant and highly valuable cases of spices we frequently carried.

Above is a typical cargo stowage plan for forward 3 hatches, for multiple Port Discharge. It should be noted, that backloading usually took place once a parcel had been discharged, and the vacant space was utilized for future Ports’ cargo sometimes immediately. It became a never-ending process that required both experience and careful planning, usually by the Cargo Officer or Chief Officer. Some ships carried a “Supercargo” who supervised the loading operations. Particular attention was required to ensure suitable segregation of various cargoes. A good example of segregation, required on the East African Coast, was when loading Salted Cow Hides, which stank and oozed a salty fluid. Because of the risk of contaminating and tainting other cargo, they needed to be stowed, well-away from other shipments, such as Coffee, Rice, Pepper, Tea and Cloves, to name but a few. Other dirty cargo included pallets of Carbon Black which could easily stain adjoining cargo with heavy black smudges, if not properly separated. Stowing both these types of cargo well-away from others often proved a challenge.

The ships I served on did not have the luxury of a Supercargo, so stowage was all down to the experience and skills of the ship’s Chief Officer.

The waters of the East African coast had its fair share of Arab dhows, both large and small. They were frequently seen trading between the smaller river ports, and these made for a wonderful sight as they made their way under wind power, with sails set, grasping for every breath of the wind. However, these dhows were often seen far out at sea. The larger oceangoing cargo dhows were more than capable of long ocean passages, often venturing into the Red Sea, Persian Gulf or as far as the west coast of India and Sri Lanka, like itinerant nomads.

After arriving from Asia or India, usually, our first Port on the East African Coast was either Mombasa or Dar-es-Salaam, depending on the cargo quantity and distribution. Mombasa is the only major seaport in Kenya and is located on what the Africans call the “Coral Coast”. It is a city steeped in history and in those days was crowded with Arab Dhows, and ashore the Colonial, Arab and Moslem heritage was further supported by the number of Churches, Mosques and Middle Eastern style architecture, especially in the old City and Port area which is dominated by Fort Jesus, built in 1593, a legacy of the Portuguese. There was also a significant Indian population, mainly proprietors of the numerous emporiums, or traders of varying persuasions. At that time, there resided quite a few Europeans and white Africans in Mombasa, many of whom worked in the port engaged as Stevedore Supervisors used to handling the local labour. It was a far cry from the sub-continent where abuse, harassment, and general mistreatment of labour was often obvious to the eye. The African labour in Kenya, engaged in stevedoring, were reasonably well treated by their European bosses, and responded accordingly in terms of effort, although there was occasionally the harsh word or two, intended to jig them along, shouted out aloud, to ensure being heard over the constant humming or chanting of native tribal songs, sung by the labourers.

In Mombasa port, when alongside the jetty, we were not limited to using ship’s gear for cargo operations, but rather electric cranes located on the wharf apron. Cargo was discharged more, or less, directly into rail wagons, obviously it was destined for somewhere other than Mombasa itself, although occasionally we may be called upon to discharge at the mid-stream buoys if there was wharf congestion.

The modern Port goes under the name of Kilindini Harbour. It has a very picturesque entrance with a large white Hotel, I think named Oceanic Hotel, although I never went there, perched on elevated ground on the starboard side as you enter the port from seaward. The Port of Mombasa is only a few miles from modern down-town Mombasa.

Many mariners will recall the inverted elephant tusks that act as a canopy spanning the approaches to the city, along Kilindini Road. Where dozens of vendors peddling their wooden carvings of antelope, giraffe, and animal skins flank the streets. It is also well known for its good hotels and resorts, many originating from the City’s colonial past.

Mombasa boasted an excellent, Flying Angel Club, which attracted a good number of patrons from ships visiting the port. Of course, there were always the others, perhaps preferring to frequent the Casablanca, Rainbow, Sunshine, or Bristol Bars that were well known at that time for their hot night entertainment. The “Mission” was a place for meeting contemporaries from other companies and ships, particularly Clan Line, T.J. Harrisons, Ellerman Line, British India Company and other Bank Line crews, to name but only a few. Memorable and boisterous soccer matches, barbeques, and various outings and excursions were organized by the Mission to Seaman. If one went to church on a Sunday, the padre often took several of us to his bungalow after the service, for a slap up breakfast of bacon and eggs. Needless to say it did much to ensuring a full house on Sundays. It was great for us apprentices who were always hungry.

All of the East African ports had their own charm and characteristics, each with something different to offer. Sailing south after Mombasa was the wonderful port of Dar-es Salaam. “Dar” as it was known, is one of my favourite East African coastal ports. It has a quaint harbour which, once having passed through the narrow entrance, is flanked on one side by a sort of sandy spit with the town, located on the opposite bank. The town is close to the docks and set back a little, nestled behind a golden beach and the inevitable swaying coconut palms. The port has since grown and changed much, but during the 1960-early 1970s there were only a couple of cargo berths, so one generally anchored in the harbour to discharge, only berthing alongside to load on the northbound sector of the round voyage.

The Seaman’s Club, of which “Dar” could boast one of the best, was always a popular venue. It featured a nice bar, restaurant, wonderful swimming pool as well as many other amenities for the seafarer. Prices were very reasonable and the service and hospitality warm and welcoming.

The other favourite pass time was fishing, especially if anchored at the inner anchorage. I have never seen so many yellow tails or jacks in my life, all of a decent size. Once the line was tossed over the side, the fish hooked themselves and surrendered. Our Chinese crew gutted and cleaned the fish as fast as they could, before freezing for eating, at some later time. This was regular evening entertainment in which most onboard participated, when not working or on duty.

Once all discharged and holds were cleaned out, we headed south down the African coast, past the Islands of Pemba and Zanzibar, off the coast of Tanganyika, slowly progressing towards the Portuguese administered colony of Mozambique, and the Ports of Beira and Lourenco Marques, in quick succession. where the Portuguese colonial influence remained strong and was still very evident during this period.

The Mozambique Channel is an important commercial seaway for vessels sailing the East and South African coastal trade routes. The channel itself is about 1,000 miles long and varies in width, between 300-600 miles and is considered the notorious breeding ground for some of the Southern Hemisphere’s most devastating cyclones. Navigators will also recall that it is very deep, and the origin of the strong ocean currents known as the Agulhas and Mozambique. These currents, which mainly run parallel to the coast of Africa, are generally fast flowing and have a very significant influence over a large distance of the African coast, from the South African Cape northwards towards the Comoros Islands at the top end of the Mozambique Channel. Such currents and tidal flows can be treacherous unless understood by mariners and treated with the respect they deserve.

The red brown waters were a tell-tale sign when approaching Beira, and in particular the estuary of the Pangoe and Buzi Rivers at the mouth of which Beira is situated. It was not uncommon to anchor off the port for a day awaiting a berth, before transitted the long buoyed channel and entering the bustling port where there were numerous general cargo facilities The port was often congested, and most of the wharfs for ocean going vessels were occupied. It was also a hub for large Portuguese passenger ships.

Beira, being the 2nd largest port in Mozambique, had quite a significant passenger trade during this era, with many regular services to and from Mozambique, mainly to Europe. This was primarily because Beira was a transit centre for two-way passenger traffic between central African nations that bordered Mozambique and the rest of the world. With air services still in their development stages, the city port was well connected with its octopus like rail links to neighbouring countries which acted as a conduit in support of its passenger ships. Additionally, Beira was a significant regional centre for transshipment of cargo to other African destinations and for coastal shipping, by virtue of its ideal geographical location and sprawling rail network system.

Lourenco Marques, named Maputo nowadays, is the largest and most populated city in Mozambique and therefore its most important port. Its continental atmosphere, pubs, bars, and café culture and charm of its inhabitants make it an ideal place to visit. It was named after the Portuguese navigator, Lourenco Marques who discovered the area in 1544. Modern day Maputo is situated on a large natural bay on the Indian Ocean, near where the rivers Tembe, Mbuluzi, Matola and Infulene converge, causing the waters to be stained the usual muddy brown. Maputo’s economy is centred around its port, through which much of Mozambique’s imports and exports are shipped. The chief exports include cotton, sugar, chromite, sisal, copra, and hardwood, which seafarers of the era will remember loading in abundant quantities. Visiting mariners may also recount the poverty of the stevedore labourers and how they turned up for work with only a hessian sack as clothing, and bare feet, a far cry from today’s obsession with Health and Safety.

In 1974 the government of Portugal was overthrown by the military. The new regime, which favoured self-determination for all of Portugal’s colonies, made efforts to resolve the conflict in Mozambique. Talks with Frelimo resulted in a mutual cease-fire and an agreement for Mozambique to become independent in June 1975.

It was not unexpected to see several passenger ships in port at the same time. Hence berths were always at a premium, sometime requiring ships to anchor awaiting their turn for a berth. However we, being on a liner service, helped to prioritize our application for a berth, so waiting time was relatively limited.

A relatively short transit further down the Natal coast brought one to Durban. It was common for ships to sail close to the coast as they proceeded ever more southerly. Being a large city, at night it was easy to detect the “Loom” of Durban from afar with the naked eye in clear conditions. The glow on the horizon was very conspicuous at a great distance.

The city and Port of Durban is the third most populous city in South Africa after Johannesburg and Cape Town and the largest city in the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal. It is a thriving city pulsing with energy, consequently, always an absolute favorite with sailors, especially in the 1960-1970s, mainly due to its free and easy lifestyle and wonderfully hospitable residents.

Durban is a truly splendid place in all ways, great beaches, complete with anti-shark nets, good hotels, a modern city, and a wide range of entertainment to suit every individual’s whim. Approaching the harbour entrance which runs more or less East-West one observed the Bluff (port side as one enters the port), an area of jetties dedicated for the loading of coal over by the old disbanded whaling station. To starboard lay the main port area and jetties, together with the actual township.

All, of the East African ports had something different to offer the visiting sailor, but Durban always felt the most familiar with its western style atmosphere and many seafront bars, restaurants, and hotels. The Playhouse Pub and Restaurant was a big attraction for all sailors with its ceiling painted to look like the sky complete with realistic looking stars, as a main attraction. It was an iconic landmark within the city of Durban.

The beach at Durban was a hit with some crew members. For the safety of swimmers and surfers it was enclosed with shark nets. How effective these nets were is open to debate, as I read somewhere most of the sharks caught in the net, were trying to get from the shore side out towards the open sea! Nevertheless, many crews just went there to eyeball the “talent”, and soak up sun and Tuskar Beer not necessarily in that order.

Other ports called on the South African coast were Port Elizabeth and East London, not to mention Cape Town. However, there is so much to write about the South African ports alone, it is worthy of its own narrative and too extensive to include in this article.

However, on the northbound leg we frequently called at secondary ports on the East African coast, such as Mtwara, Tanga, Zanzibar, Pemba Island, and Lindi. In most cases, we visited these ports to load high revenue parcels of cargo, such as tea, cloves, coffee, and high-grade lumber, all for the Far East. Mtwara in south east Tanganyika, was initially constructed during the British colonial period. It lies close to the Mozambique border and now offers deep water facilities, but during the 1960-1970s it had not been fully developed, we mostly worked at anchor only occasionally going alongside, when working larger quantities of cargo. In Tanga, it was a similar story, another small port during my time but this port has now become the second largest in Tanzania, offering deep water berths and extensive port facilities.

In Zanzibar the port lies on the west side of Zanzibar Island, about 20 nautical miles off the coast of Tanzania. Zanzibar is a semi-autonomous region of Tanzania. It is composed of the Zanzibar Archipelago group of islands.

The island’s main exports were cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, and black pepper, all of which we loaded every voyage. For this reason, the Zanzibar Archipelago, together with Tanzania’s Mafia Island, are sometimes referred to locally as the “Spice Islands”, a term borrowed from the Maluku Islands of Indonesia. Zanzibar was first occupied by the Portuguese, and still retains a strong Arabic connection, evidenced by the large number of Arab dhows seen sailing in the region, traversing its pristine waters. The islands’ stunning beauty, archeology, and architecture, together with its snow-white sandy beaches are a wonder to behold.

These are just a few of the many nostalgic memories I hold of days sailing in these interesting waters and the exciting trading route between East Africa and the Far East in which I was engaged for a good few years.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item