One must ask if the name Blythe Star was a ship’s name fraught with bad luck.

The original vessel to bear the name Blythe Star was a 306 gross tons, timber built twin screw motor vessel (above), built at Prince of Wales Bay, Hobart, by the Australian Commonwealth Government Shipyards in 1945, to the order of the Leven Shipping Co. Pty. Ltd. She was fitted with twin six-cylinder Ruston-Hornsby diesels developing 408 BHP. The ship was destined to have an unfortunate career. On 5 June 1951 she was stranded at Leven Heads while outward bound, but floated off undamaged at high tide the following day. Then on 8th May 1953, fire broke out while tied up at South Wharf, Port of Melbourne, gutting much of her superstructure, including the crew accommodation. Sadly, the second engineer lost his life in the explosion. Due to the extent of fire damage, she did not re-enter service until March 1957 following substantial repairs.

Subsequently, on 17th May 1959, whilst on a voyage from Ulverstone, Tasmania, to Melbourne with a cargo of timber and canned peas, while approximately 5 nautical miles north of Burnie, there was an explosion in the engine room, killing the second engineer and setting the vessel ablaze. The hull drifted about until finally it burned to the waterline and eventually sank. The 10 surviving crew managed to make it to Burnie in the ship’s lifeboat. An inquiry found that no one could be blamed for the loss of the vessel, although the reason for the explosion was never ascertained.

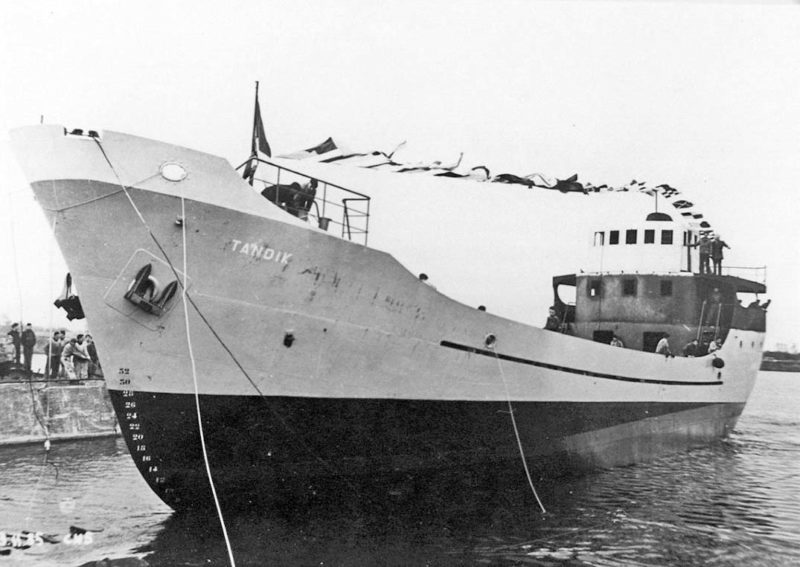

The owners subsequently purchased a replacement vessel, an ex-Norwegian coaster named Tandik and renamed her Blythe Star.

I remember being on leave in Melbourne in October 1973 and reading a report in the daily newspaper about the “mysterious disappearance of the coastal ship Blythe Star, a coastal trader that had disappeared without trace, somewhere off the coast of Tasmania. The Blythe Star was a very small coaster of only 321 tons gross, Length of 44m, Beam 7.6m, and a draft of 3.0m. She was equipped with a diesel engine of 490 BHP which gave her a service speed of 10 knots, and she normally carried a crew of 10.

The ship had been built in France by Ateliers Ducheans and Bossiere at Le Havre, and was launched in 1955 as the Tandik for Norwegian owners Rederi A/S Orion of Drammen (above).

The vessel was procured by the Bass Strait Shipping Company in 1960 and renamed Blythe Star (above). She was operated by the Tasmanian Transport Commission engaged in short voyages around Tasmania and the adjacent islands, also across the Bass Strait to mainland Australia.

On 12th October 1973, the Blythe Star left Prince of Wales Bay, Hobart, Tasmania, bound for the small port of Grassy on King Island, which is located to the northwest of Tasmania in the Bass Strait. She was carrying a cargo of pelletized superphosphate fertilizer in bags, together with kegs of beer. It was reported that sea conditions were calm with a gentle swell at the time of her departure. A lighthouse keeper reported the ship passing Maatsuyker Island at 5.15 am on 13th October, from whence she proceeded up the west coast of Tasmania towards King Island. However, at the time the regulations did not stipulate daily vessel radio reporting, so no one was aware of whether the ship was proceeding east or westbound towards King Island, although the sighting off Maatsuyker Island, would have indicated the westerly route rather than that the easterly. On her fatal voyage the Master opted to take the west coast route due to the placid weather.

There were two routes to King Island, southbound via the west coast direct to King Island and the longer northbound east coastal route, passing the top of Tasmania to King Island. The selection of the route was at the discretion of the Master and was mainly influenced by prevailing weather conditions at the time.

Early next morning the weather was still fine with the vessel following its normal course a few miles off the Southwest Cape of Tasmania, when suddenly, between 8.00-8.30 am the vessel developed a starboard list. After a brief period of stabilizing the list again developed more to starboard and increased dramatically until much of the starboard side was below water, causing sea water to ingress into the vessel through unsecured openings.

Those crew members asleep below decks were thrown from their bunks, causing all the crew to struggle to make their way through rising water to the aft deck area. The capsize of the vessel appears to have been sudden and completely unexpected by the crew.

Due to the severe angle of the list the ship’s lifeboat was unable to be launched. However, an inflatable life-raft was released into the sea by the boatswain. Once inflated, the crew all managed to board it and it was cut free of the ship by a crewmember. Very shortly afterwards, Blythe Star’s bow raised high, and the ship sank stern-first below the waves into the Southern Ocean. By this time the ship was about 5 nautical miles west of Southwest Cape in approximately 80 fathoms of water. No distress call had been made by the captain as he had no time before the vessel capsized, it had all happened so quickly.

The inflatable life-raft into which the crew had escaped was 3.7m in diameter, covered with an orange canopy, and equipped with tinned water, old biscuits, some flares, two oars and a baler. In the rush to abandon ship, the emergency portable radio had been left onboard the Blythe Star, however, the crew were confident they would soon be spotted by searchers or passing ships. However, this was not to be, and several days passed during which the weather had worsened significantly. Keeping the raft upright and afloat took considerable effort on the part of the survivors, with waves regularly swamping the life-raft causing it to collapse onto itself, and seawater needed to be constantly bailed-out.

Over the ensuing days, the raft remained undetected and drifted south-eastward around the south of Tasmania, increasing the distance drifted from land. After three days of worsening conditions, sadly the Second Engineer, died, possibly due to a lack of his normal medication and he was slid into the sea the next evening. A welcome weather change then carried them north as far as Schouten Island off the Freycinet Peninsula, following which the raft drifted south-westerly approximately parallel to Tasmania’s eastern coastline. On the ninth day, they came close to a small rocky bay and the crew were able to successfully paddle and eventually made landfall on the Forestier Peninsula at Deep Glen Bay.

Almost immediately, the nine survivors attempted to find an overland route out of the bay. The steep, precipitous cliffs and almost impenetrable vegetation made any progress exhausting and within a short period another two crewmen, died of suspected of exhaustion and hypothermia. Eventually, the small group of three set out together and over the next day and night managed to scale the cliffs and force their way through the rainforest until they came to a rough track. Almost immediately, a vehicle was heard approaching, believed to be a local forester. The three were eventually taken to the nearby township of Dunalley, where a helicopter was quickly arranged to collect the remaining four crew members from Deep Glen Bay. The men had not eaten in four days and memorial services had already been held for some of them, as they had been believed to have been lost at sea. All seven survivors recovered despite spending time in hospital.

Since two possible routes existed for a voyage to King Island located off Tasmania’s north-west corner, unfortunately for all concerned, no notice had been left by the Blythe Star as to which direction the vessel would take, and this immediately compromised the efficiency of the air search operation that was launched on 15th October when she failed to arrive at King Island and no radio contact had been received.

An air search was conducted employing nine military aircraft, co-ordinated by the Marine Operations Centre in Canberra. After seven days of searching, it was decided to abandon the full-scale search. Despite the most extensive air-sea search yet conducted in Australia, comprising of 14 aircraft, no trace of the vessel was ever found and was ceased on 23rd October 1973.

However on 12th April 2023 the wreck was discovered by the research vessel Investigator during a 38 day research voyage to study a submarine landslide off the west coast of Tasmania. A plaque has now been unveiled in Hobart commemorating the 50th anniversary of the sinking.

Parliament decided to appoint a committee to investigate the circumstances as to why the life-raft and survivors were not located during the search, and to consider measures to facilitate the better location of distressed vessels or survivors in future. A Court of Marine Inquiry was announced by the Government to start later that year. This judicial inquiry followed an earlier preliminary investigation headed by Captain Taylor. The court of inquiry was held at Melbourne between 3rd December 1973 and 14th February 1974.

A report, “Loss of MV Blythe Star” was published by R. J. Herd in January 1974, possibly as part of the Court of Inquiry being conducted at that time, with a summary of its findings. Herd concluded that while there was no evidence that the vessel was overloaded or incorrectly loaded, it seems likely that ‘free surface’ effect in the ships lower ballast or double bottom tanks inadvertently, fatally impaired the ship’s stability. In the scenario hypothesized, one of the main ballast tanks in the vessel’s double-bottomed hull may have been drained to the level where a broad free water surface was created low down in the ship, and this would significantly compromise the vessel’s rolling stability. Causing the ship to assume an ‘Angle of Loll’ from which she could not recover since its righting lever to bring the ship upright again after heeling over was zero. The ship was in imminent danger of capsizing.

The Blythe Star sinking brought about changes in Australian Maritime Regulations. All ships in Australian waters were then required to report their position at least once daily (AUSREP) and all ships must lodge voyage plans prior to departure or entering Australian waters. Furthermore, Electronic Position Indicating Radio Beacons (Epirbs) must be carried by all ships and Lifeboats.

Some 50 years after the sinking of the Blythe Star her wreck was located by fishermen trawling in the area of South West Cape, and also by the location of the ship’s bell, which placed the identity of the wreck beyond doubt.

Not long after this there was yet another casualty, this time in the Port of Melbourne, the Straitsman (above) on 23rd March 1974. It so happens I was working on another vessel some distance away, but also at South Wharf, when the tragedy occurred, and I do remember seeing the vessel passing us on her way upstream towards her designated berth, where she always docked.

The Straitsman of 727 grt, built in 1972 by North Queensland Engineers and Agents Pty. Ltd., (NQEA) Cairns, Queensland for R.N. Hough and Co., Launceston, Tasmania, principally as a livestock carrier, but also with the capacity to carry general. Unfortunately, soon after entering service the owners were declared bankrupt and the ship was sold to the Tasmanian Transport Commission late in 1972.

The Straitsman was a roll-on/roll-off ferry and livestock carrier, built for the Bass Strait trade between Tasmania and Victoria.

She capsized and sank in the Yarra River, Melbourne on 23rd March 1974 while approaching her berth stern first, with her vehicle door partly open, with the loss of two crew members and many of her cargo of 2,000 sheep (above). The ferry was heading up the Yarra River towards #22 South Wharf at about 6 knots when a crew member opened the stern door without the knowledge of the captain on the bridge.

After capsizing, the ship was salvaged and raised in April 1974, re-entering service in 1975 after an extensive refit and rebuild. In 1991 she was sold to L.D. Marine and Ship Repairs of Launceston, who chartered her out to Strait Shipping Co., Picton, New Zealand to carry livestock across Cook Strait. Then in June 1994 the Straits Shipping Co. purchased her and placed her on the Wellington-Picton-Nelson service, mainly carrying livestock.

Eventually, in 2002 she became surplus to requirements and was laid-up at Wellington where she remained until 2004, before being sold to Fijian owners, Venu Shipping Ltd., for further trading and was renamed Sinu-I-Wasa.

On 20th February 2016 she became a total loss after running aground in the south eastern approaches to the Fiji Islands during Cyclone Winston.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item