M.V. Ernebank

In 1953, I joined the old timer, M.V. Ernebank in Bromborough Dock, Birkenhead.

So commenced a memorable voyage around the world which lasted eight months and took in both the Panama and Suez canals, and in the process, considerably advanced my education. She was a stately looking vessel to my eyes, with a long wood sheathed foredeck, of Oregon pine, and open rails. It was a voyage with quite a few ‘firsts’ for me, an eighteen year old apprentice, still not quite dry behind the ears! There were three of us, a tough looking Aberdonian, who was actually a gentle character, and who was to become a good friend, and a first tripper from Bearsden, near Glasgow. Our stay in Birkenhead was extended as we drydocked after discharge, probably for a 15 year survey. The trip was a riot from the start as we guzzled up to 12 pints a night in the pubs of Birkenhead, something I had never done before. I also discovered New Brighton pier and dancehall, which burned down in later years, and where huge crowds jived to loud music and where the darkened balcony was a convenient place for dozens of snogging couples. It was a foretaste of the ‘swinging sixties’, still to come. My new friend from Aberdeen led the way, and to finish off we usually found some local girls to walk home. This lifestyle was a revelation to me, and it was only a small taste of promising things to come.

So commenced a memorable voyage around the world which lasted eight months and took in both the Panama and Suez canals, and in the process, considerably advanced my education. She was a stately looking vessel to my eyes, with a long wood sheathed foredeck, of Oregon pine, and open rails. It was a voyage with quite a few ‘firsts’ for me, an eighteen year old apprentice, still not quite dry behind the ears! There were three of us, a tough looking Aberdonian, who was actually a gentle character, and who was to become a good friend, and a first tripper from Bearsden, near Glasgow. Our stay in Birkenhead was extended as we drydocked after discharge, probably for a 15 year survey. The trip was a riot from the start as we guzzled up to 12 pints a night in the pubs of Birkenhead, something I had never done before. I also discovered New Brighton pier and dancehall, which burned down in later years, and where huge crowds jived to loud music and where the darkened balcony was a convenient place for dozens of snogging couples. It was a foretaste of the ‘swinging sixties’, still to come. My new friend from Aberdeen led the way, and to finish off we usually found some local girls to walk home. This lifestyle was a revelation to me, and it was only a small taste of promising things to come.

The Ernebank was a typical pre-war Bank Line ship with 5 hatches, and rather pleasing but unpretentious lines, built by Harland and Wolff in Belfast, 431ft long, with a four cylinder Burmeister & Wain diesel engine giving her a decent 13 knots. Built as a shelter deck vessel, with the normal small tonnage hatch aft, she enjoyed the advantage of reduced dues on account of her low measured tonnage of 5,388 net.

We were discharging Copra and valuable coconut oil, and it was a regular feature of the Bank Line trading pattern which brought their ships back to the UK and the end to what were often very long voyages. A few ships enjoyed ‘short’ 6 to 8 months voyages on a more or less regular basis, and these were christened ‘Copra ships’.’They were much sought after by some, but by no means all of us!

The first sight of the ship, rounding the quayside shed in a taxi, always gave me a thrill. It was a mixture of apprehension and pride. Never mind that the hull might be a bit rust streaked or that the gangway looked rickety, it was home for possibly 2 years, the length of the articles. The familiar sound of steam winches, hissing and clanking as they worked was music to my ears. The deck was cluttered with hatch boards, steel beams, and a variety of repair pipes and hoses, and even this sight felt comforting in a strange sort of way. There would also be a rich pungent smell of coconut oil, which was being pumped ashore with temperature raised to keep it liquid and flowing. On board, the first task was to locate my cabin and meet new shipmates. What would they be like, and who is the all important Captain who would play God for the foreseeable future?

Conditions on board were basic, if not primitive. Air conditioning was yet to be fitted on ships, so we relied on simple fans, with oscillating ones being much prized. Metal scoops were jammed in the port openings to catch any air, and in port it could be stifling, especially at night. Fresh water had to be pumped by hand, and was strictly rationed. The apprentices were charged with topping up the washing water for the officers as well as for their own use. It happened occasionally that water needed to be pumped from the forepeak, rather than the small domestic tanks amidships, and this was no mean feat at sea when there was a seaway running. I can still remember struggling forward, buckets in hand, the deck often glistening in the wet, and descending down the forepeak hatch to swing on a semi-rotary pump. The other apprentice stood by the buckets on deck and was supposed to call down when the job was done. There were occasions when relations were not good and he simply walked away leaving me pumping!

We finally sailed down the Mersey, and I was on the forecastle watching the Liver birds slowly coming in line. My journey began at this point, and ended as they lined up on return. It was my private little world. This was to be a very happy ship, with no dissension, and great camaraderie, which was not always the case.

First stop was Cuba, to load bagged sugar. As we left UK waters, I had my familiar feeling of euphoria. A couple of days out, the grey skies lightened, the sun beamed down, whales thrashed their tails on the water, and flying fish were picked off the foredeck in the morning by the Chinese carpenter as he did his rounds sounding the tanks.

The loading ports were along the south coast, starting with Niquero in the Granma province of Cuba. Castro had yet to wrestle control of the country, so it was the hedonistic Cuba of Batista that we were to sample. Here we all ended up in a bordello, my first. My companions from the ship believed in the ‘work hard, play hard’ school of life, and they showed me the way. There was a sort of bar and dance hall with benches round the sides and typical Cuban music blaring out. Dodgy looking characters, other than our party that is, were sitting around or leaning on their partners on the dance floor. It was an era of fantastic sounds which I privately called ‘chop chop’ music on account of the heavy rhythm. The ‘ladies’ of the establishment were mostly care worn, to put it politely, but they looked somewhat better after we had a few glasses of rum. The locals drank it straight out of the bottle. Next stop was a captivating little town called San Ramon. It had a single jetty which we tied up to, and this had a single track railway running down from the factory on high ground behind the town. The procedure was that loaded trucks were despatched from the factory, and ran down the hill by gravity, controlled only by a man perched on top with a crude screw down brake. He often looked terrified, and for good reason as accidents were common, and a man was unfortunately killed during our period loading. This led to a day of mourning. The trucks thundered through the centre of the little town, where chickens and children scattered on hearing the approach. We sat drinking the potent white rum of Cuba at the bar tables either side of the track and watched the pantomime, fascinated.

When we were full, around the 10,000 ton mark, we sailed for New Orleans, a very short journey, and probably the shortest trip I would ever make with a fully loaded cargo. After the long run up the Mississippi, we tied up in Algiers to discharge, on the far shore of the river from New Orleans. Canal Street, was easily reached, however, where we could find the Walgreens and Walmart stores. Here was an opportunity to stock up with all sorts of items. For me, it was the great ‘Sea Island’ cotton khaki shirts and pants which were such good quality. Also mundane things like heavy duty fishing line for the Pacific stops. Fishing was popular with all on board, and there were many occasions around the islands when we enjoyed the bonus of watching the fish take the bait, often deep down when the water was perfectly clear. When we stopped temporarily at sea for the engineers to carry out an essential repair, the lines went straight over to see what might be caught. We never knew the variety and size of the catch, which could be enormous and stretch the full length of a bathtub.

Then, surprisingly, after discharge, it was back over to Cuba for a full load of sugar, this time for Japan.

We loaded on the north side of the island, way offshore, almost out of sight of land. Here there are large groups of smaller islands, and we anchored to receive the sugar from barges. It was a port for Caibairen, the town a short way inland, and we lay at anchor in crystal clear water, teeming with fish. Due to the very warm nights, we decided as apprentices to sleep on deck under the stars, and we set to, making folding canvas bunks which worked brilliantly. During this stay at anchor, the coronation of the present Queen took place. The time difference with the UK meant that it was early in the morning for us, and our Scottish nationalist engineers all gathered around the radio hoping to hear about a possible interruption that had gathered credence, when the famous Stone of Scone would be recovered for Scotland. They were disappointed. The stevedores offshore were the toughest I have ever seen, and they were mostly bow legged, which I imagined was from the work staggering round the holds with the sacks of damp brown sugar, each of which weighed 2 cwt. At lunchtime a boat would deliver beer in crates, and many of the workers fished for their lunch. I recall seeing them remove the beer caps with their teeth, and some actually bit into live fish as they came over the rail. It was an amazing sight, which I have never seen since. This stop was also the place where I became seriously ill with too much white rum. It was beyond drunk, and I have never touched rum in the 63 years since.

We transitted the Panama Canal, and early on in the Pacific voyage to Yokohama, the Captain, who was a real gent from the Shetland Islands showed us apprentices how to make fudge from brown sugar. He was a true seaman who could snap sail twine with his beefy hands, and he encouraged us lads in many ways, passing on his knowledge. For the fudge, we ‘found’ some sugar from the holds, and the technique was to simply mix in condensed milk using big tin trays placed on the galley stove. The end product could be hard and brittle, or soft and bendy, depending on the time over the heat.

The ship was painted down during the 4 week crossing, the usual procedure away from the hustle and bustle of life in port. I also taught my Aberdeen friend how to play chess, which we did sitting out on deck.

Yokohama was heaven. We lay at anchor in the bay, and the winches clattered away 24/7 as we discharged through the night with lights. Ashore can only be described as a paradise for us youngsters. I can still recall the name of the particular bar which we made home. It was called ‘Bar 9 of Hearts’, probably long gone, but here we found beautiful willing girls whose job it was to entertain us. We played card games, mostly strip poker, for fun, and a great time was had by all. Japan was only 8 years out of WW2, and the American occupation was very evident, creating a fascinating mixed western and oriental atmosphere. Kobe, and the big port of Moji were the other discharge ports, but our thoughts stayed with Yokohama where we had enjoyed ourselves so much. Our shipboard duties meant that my fellow apprentice and I reluctantly had to share our imagined romance with the same girl on alternate nights! It’s tough at sea. There were more trips to ‘Girlie houses’ in Kobe, the second engineer leading the charge. As the comedian of the party, he led the way, and we arrived at a particular venue he had chosen where we were ushered into a reception room with drinks laid out. As the spokesman he said “not now”. Then, after a pause, “In five minutes”, when the Madam of the place politely asked us if we wanted girls to join us for drinks. Some of our other antics are best left out of this narrative! These bars or girlie houses were very common at the time, no doubt because of the large number of American military still in residence. There was one embarrassing and cringe worthy episode when we chose our partners for the night, only for the kitty to come up short. I had taken a strong fancy to a very attractive young girl, and she was keen for us both to disappear into the night, but it wasn’t to be.

Before leaving Japan we bought all the new gadgets freshly available, like the novel transistor radios and binoculars for bridge work. It was the post war period in history when Japanese goods were shoddy, the lenses falling out of the binoculars, or worse. We still bought them however, and I cherished a little black leather covered Sony transistor that kept me in touch with the world for months. It sat snug in the porthole, held tight by the weight of the heavy brass port itself.

Word came through that we were to load Copra for home. It was to be a short trip after all. Elation by some, but we still had to go through the slow and tortuous process of trawling round the Pacific islands loading. The sequence of ports to visit included Honiara in the Solomon Islands, the scene of heavy fighting by American troops in WW2, and Gizo. The island of Samari, where it was possible to walk right around, and finally Rabaul in East New Britain. We commenced the necessary hold cleaning, which was mainly sweeping and bilge clearing, and this was carried out by the Indian crew and Chinese carpenter, plus the Apprentices.

All went well in our island hopping, with some unconventional berthing to suit the local conditions, including the use of a convenient tree stump. In Rabaul, we tied up alongside the hull of a wreck, which became officially the ‘wreck berth’ for many years, and as the name suggests, it was the levelled top of a sunken vessel, one of dozens littering the big harbour. Signs of the fierce fighting was everywhere, although some 8 years had elapsed. The glint of crashed aluminium Japanese fighter planes could be seen high up in the jungle, and we trekked up to have a closer look.

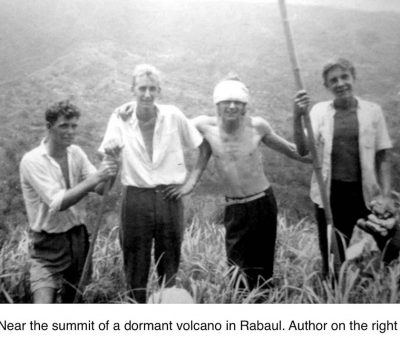

In a moment of madness we also chose to climb a prominent volcano overlooking the port, and this took our party through cultivated fields of pineapple plants.

Rabaul residents are famed as great drinkers, and we fell in with the Australian stevedores who seemed to party at every opportunity. There were some bizarre moments during our stay when I staggered back across fields in the dark after excusing myself from a heavy session. I could see the port in the distance, but a garish, very noisy, and colourful event stood in my path. Maybe it was my tipsy state, but UFO sprang immediately to mind. I was in pitch black surroundings, wading through quite long grass. As I drew close, I realised it was my first view of some captivating Chinese opera being staged largely for the sizeable Chinese community in Rabaul. I loved it, and have been hooked ever since.

After a number of weeks we had completed loading. It was my first experience among the charming New Guinea people with their amazing pidgin language which we were eager to mimic. ‘Shoot lamp’ for a torch was my favourite expression. They were also great exponents with a fishing spear, and we would watch fascinated while they expertly fished around our berths.

Before sailing for the Red Sea and home, the Ernebank bunkered at Balikpapan in Borneo. Here we were sold spirits from the bum boats, labelled Whisky, Gin, and Rum, but in reality all the bottles contained the same strong spirit. Only the labels were different.

In the Red Sea, steaming up towards the Suez Canal, there was a following wind for a long period. This created a still atmosphere on board in which the tenacious Copra bugs flourished. These little black Beatles thrive wherever there is coconut, and we were heavily infested. They were in the bread which necessitated holding slices up to the light to pinch out the offenders, and they got everywhere. This habit became automatic, and stayed with me for years afterwards. We amused ourselves by dropping them in buckets of water, but they merely sank to the bottom and walked out up the sides. It was hard not to marvel at them. When it was particularly unbearable, the ship steamed around 360 degrees, which had the effect of blowing millions of them off in a big black cloud as we came up into the wind.

The passage home went smoothly otherwise, and after transitting the Suez Canal at night, we passed through the Mediterranean Sea and onwards to the Mersey. The cargo of oil and Copra was destined for the Lever Bros. plant in Birkenhead, and we anchored in the centre of the Mersey for the formalities, 8 months out. I saw the Liver birds slowly come into line a we steamed past, marking my silent completion of the round trip. Because we had been in Japan, the customs rummager’s took a particular interest in our declarations. In my case I had a ton of goods, including a bolt of Shantung silk which my dear old Mum had requested. What to do about declarations? Most of us spirited away the offending items to favourite hiding places in the time honoured fashion. I craftily chose the space below the saloon seats where the Customs team were sitting. It was a great inspiration, and worked perfectly. You could say they kept my stuff warm for me, but there was a snag. When the time came for me to say goodby and depart, they were still sitting, chatting, while I fretted outside.

Eventually, I did make it home, and a few days later a full box of Aberdeen kippers arrived at the door, a kindly gift from my recent shipmate.

Like all voyages in the iconic Bank Line, this had been an adventure that could not have been bought. With the passage of time, it has become clearer to me how lucky and privileged I was to have enjoyed such a memorable trip.

An account of this and other voyages is contained in the author’s book entitled – “Any Budding Sailors?”

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item