The Bank Line’s founder Andrew Weir was born in Kircaldy, Fyfe, on 24th April, 1865. He was the first son of the cork merchants William and Janet Weir. After being educated at the Kirkcaldy High School where he specialised in finance, Andrew started his working life for the Commercial Bank of Scotland. His second employment was in a ship owner’s office where he embarked upon the basics of ship management, and from what he learned it soon became apparent that his future was in the shipping industry.

Just a month after turning twenty years of age, on 5th May 1885, Andrew Weir opened his own shipping office in Glasgow which was originally named the ANDREW WEIR SHIPPING & TRADING Co. Ltd. (Later to be named Bank Line).

Here we look at the first vessels of this famous company.

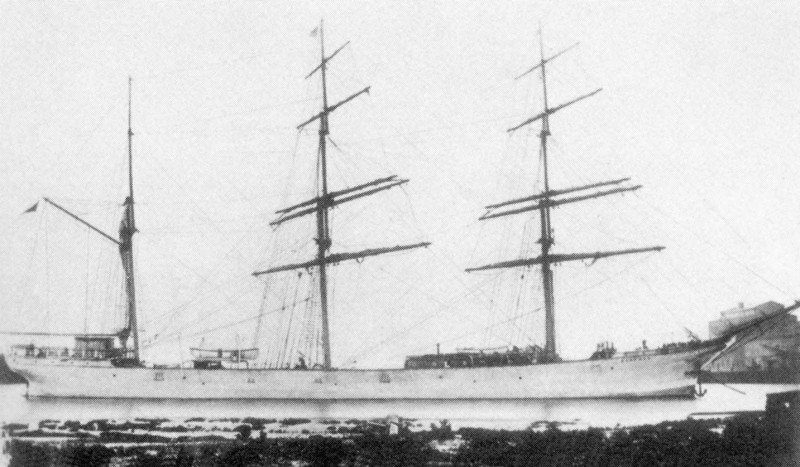

Willowbank

On 22nd December 1885 the young entrepreneur acquired a 24 year old three masted barque named Willowbank. That 882 ton vessel was built by Wigham Richardson on the Tyne in 1861 as the Ambrose. Her first owner was Schillizzi & Co. of Liverpool, but he sold her to another Merseyside ship owner named E. Bates in 1876. Then another Liverpool company J. & F. Gibb & Co. bought the barque in 1884 and re-named her Willowbank.

The insurance premium on a ship has always been an expensive part of its operating costs, and ship owners who bought their ships on mortgage had to have the vessel fully insured in case the ship was lost. But if that ship was purchased for cash, the insurance on the same ship was not compulsory. Many ship owners started off by obtaining an old unwanted ship at a very low price for cash, then after getting a charter sent it to sea without insurance. Lending banks or other financial institutions would not lend money to purchase such a ship, and the young businessman undoubtedly obtained the Willowbank for a very low price in a cash sale, then when he obtained a charter he sent her to sea, but it is doubtful if the ship or its crew were insured.

However, Andrew Weir was very lucky in his early days of ship owning. Willowbank managed to survive for ten years and probably paid for herself over and over again before she met her fate, and by which time the company was well established. If on the other hand the Willowbank had been lost on her first voyage under Andrew Weir’s ownership, it is doubtful if the Bank Line of Glasgow would ever have come into existence. It would appear that Willowbank’s suffix of ‘Bank’ led to the naming of The ‘Bank’ Line, and later on as a suffix for many of Weir’s ships. But ten years later in December 1895 the Willowbank was run down and sunk by the SS Berlin, a steamer which had previously belonged to the Inman Line of Liverpool, was at one time the world’s most luxurious passenger liner. For 21 years that liner which was then named City of Berlin, had run between Liverpool and New York.

She could carry over 2,000 passengers and steam at a service speed of 15 knots. After being sold to the American Line in 1895 her name changed to Berlin. However, it was when she was on her first ever venture into the English Channel that she collided with and sank the 34 year old Willowbank off Portland Bill.

A report from a local Plymouth newspaper gave the following account:

On the arrival of the cruiser HMS Blake at Plymouth on 23rd December 1895, she reported a fatal collision off Portland Bill. The cruiser had been about 14 miles South West of Portland in foggy weather at 0500 hrs on 22nd December when she observed the American Line passenger ship SS Berlin hove to. In answer to a signal from HMS Blake, the Berlin replied saying she did not require assistance for herself, but needed it for a ship named Willowbank that she’d collided with. The Glasgow ship had sunk, and the Berlin had launched three boats in a three hour long search looking for survivors but none could be found, just one empty lifeboat. The Berlin which had a large hole in her starboard bow headed back towards Southampton where she was towed in by two tugs and berthed at the Empress Dock for repairs. Willowbank’s captain, his wife and a crew of fourteen were lost.

Anne Main

The next sailing vessel to join the company after the Willowbank was the 449 ton barque rigged Anne Main. Length 156 feet and beam 28 feet. She had been built in 1867 on the Clyde by Alexander Stephen & Co. with a yard number 109. Captain William S. Main who lived in the Wirral was the Anne Main’s first owner and master. He named the ship after his wife and registered her in Liverpool. The Glasgow ship owner Thomas Skinner purchased the vessel from him in 1884, but shortly after putting her on the Glasgow register he sold the iron three masted barque to Andrew Weir in 1886. That ship with a deadweight of about 700 tons was to be the smallest of all the ships that Andrew Weir owned. Ten years later in 1896, the Anne Main which was carrying case oil from Philadelphia towards Japan ran aground and was wrecked on Goto Island off Nagasaki.

Thornliebank

The very first ship to be built specifically for the Andrew Weir Shipping & Trading Company, was the 1,492 gross ton three masted barque Thornliebank. Built by Joseph Russell of Port Glasgow in 1886, her dimensions were 244.5 x 37.6 x 21.5 feet. However, on 6th August 1891 when she was five years old, and shortly after dropping her anchor at Owens Anchorage, Cockburn Sound, Western Australia she caught fire. Although the blaze was extinguished by the crew after a two day battle, it was due to the many twisted beams and plates that the ship was written off. At a subsequent Court of inquiry held four days later on 10th august, the cause of the fire could not be ascertained and the crew were exonerated. Had the accident occurred in the UK the ship could have been repaired, but in the fledgling Western Australia there were no such facilities in those early years. As a consequence the Thornliebank’s hull was sold to J. & W. Bateman. They used her as a coal hulk in Fremantle before she was sold to McIlwraith & McEacharn. However, on 18th April 1928, when the Thornliebank had rusted away and was beyond economical repair, the 42 year old ship that was once the pride of the fleet, and Andrew Weir’s first designed ship, caught fire and was towed out to the nearby Rottnest Island and sent to the bottom. Owen’s Anchorage where the Thornliebank caught fire was a favourite spot where captains ran their ship up onto the beach for careening. It seems likely, that if at the time of the fire the ship was high and dry, any water required to douse the flames would have to have been carried a long distance in wooden fire buckets.

Trongate

The iron barque Trongate which was named after a Glasgow thoroughfare was the next ship to be bought into the company. She’d been built by Dobie of Glasgow in 1878 for E. L. Alexander of the same port. Her maiden voyage began on 7th November 1878 from Liverpool towards Sydney. Captain Tait was her master and his complement of 19 consisted of 2 mates, carpenter, cook, steward, 10 ABs, 2 ordinary seamen and 2 apprentices. There was one passenger on the passage. After one voyage for E. L. Alexander, William Denny was the next owner of the ship and under him part of the ship’s history occurred on 6th September 1880 when she was on passage from Antwerp towards New York. Carrying a cargo of railway lines the Trongate which was sailing in the fog in 45° North 47° West collided with the SS Anglia of the anchor Line.

From The New York Times 29th September 1880:

Captain Dunn the master of the Trongate wrote. We sailed from Antwerp on 15th August 1880 for New York. Everything proceeded favourably until 6th September, when the ship ran into a thick fog and a heavy swell. At 3pm the Trongate was close hauled on a starboard tack when the Anchor Line ship SS Anglia ran into us. She being three days out of Boston towards London was carrying general cargo and cattle. The Trongate received considerable damage to the forepart losing her head, bowsprit and jib-boom and all that was attached. After the collision the two ships separated. We proceeded to secure our head stays and temporarily repair the damage in order to proceed on the passage. About two hours after the collision the boats of the SS Anglia came alongside us in the fog and said their ship was sinking. Soon afterwards her boilers blew and she went down. I took the crew and their boats on board and bore away for St. John’s, Newfoundland. On arrival at that port they went ashore in their own boats. Both ships were British and both were insured. Except for the Anglia’s cattle no lives had been lost on either ship. We then proceeded to New York where we arrived on 28th September 1880. The enquiry will be held in London at a later date.

Andrew Weir bought the Trongate in 1891 and put her on the Australia, Americas and the UK trade with coal and wheat until 1909. At that time the number of his steam ships were increasing while those of his sailing ships were decreasing. However, after having had a good dusting in the Pacific Ocean, in 1909 the Trongate was sold. Trading under the Chilean flag she was hulked at Valparaiso in 1917. Eight years later in 1924 she was sold locally to Borquez y Cia and sailed again as the Luis a Goni. But because of her age and condition she was sold to a Spanish company and re-named Nanolo before being broken up at La Spezia in the following year of 1925.

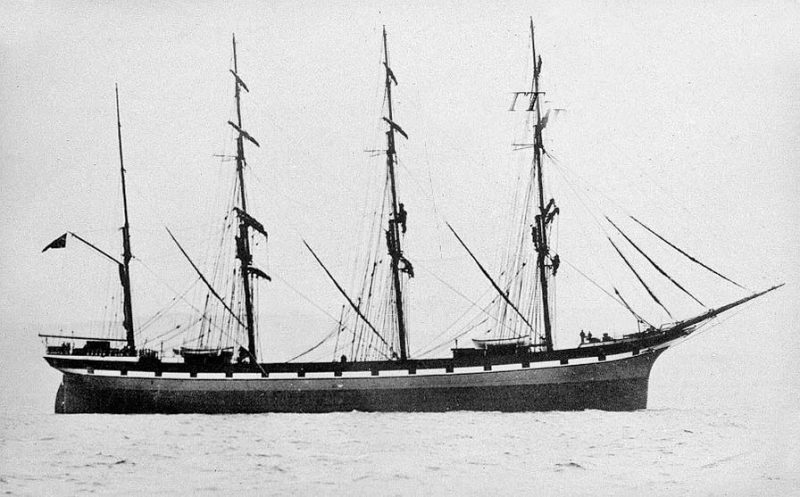

Elmbank

Built in 1890 by Joseph Russell at Port Glasgow was the steel 2,218 grt four masted barque Elmbank. Her dimensions were 279 x 41.9 x 24.25 feet. She was owned and managed by Andrew Weir of 71 Wellington Street, Glasgow.

Because this ship was less than four years old when she came to her end, little can be found on what short history she had. However on her last voyage in 1893, it is known that she took a cargo of nitrates from Caleta Bueno, Chile, to Le Havre. However the ship was lost on the run to Greenock when she piled up on the isle of Arran.

Below is a condensed account of her loss at the subsequent Marine Enquiry at Glasgow:

After having discharged her cargo at Havre, the Elmbank was ballasted with 720 tons of rubble, 20 tons of fresh water, and about 30 tons of dunnage wood and lining boards, thus giving a total ballast weight of about 770 tons. Her draught when ballasted was 10 ft. 11 in. forward, and 11 ft. 1 in. aft. On 6th January 1894 she left Havre for Greenock under the charge of the Glasgow tug Hercules with Charles Morrison in command. The Elmbank was under the command of Captain Alexander Greig, who held a certificate of competency numbered 02260. She had a crew of 16 runners as well as the master’s wife and two children making 19 souls on board. The 4½ inch towing wire which belonged to the tug, was made fast to the Elmbank by passing the end of the ship’s mooring chain through the thimble of the tow rope, and then bringing the end back through the same hawse pipe on the starboard side.

All went well on the passage around Land’s End and up St. George’s Channel, and at 2.15pm on 9th January the Calf of Man bore E by S ½ S. From this position a course N by E was set and the Walker’s patent log was streamed. The wind was fresh from SSE and increasing, while the weather was described as being misty but getting thicker. From 2.15pm the vessel had the ebb tide setting her to the NW but the Mull of Galloway light could not be seen. At 8pm the master instructed the mate who had just been relieved by the boatswain, who was acting as second mate, to see what the reading was on the Walker’s patent log. The mate found that the distance run was 47 miles. With this information he entered the chartroom along with the master to consult the chart in reference to the ship’s position. But they had barely got the chart on the table when they heard three blasts from the tug’s whistle, which both the master and his mate thought was a signal meaning, “I am making for an anchorage.” The master and mate rushed out on deck to find the tug going hard across their bows. According to the inquiry witnesses, the helm of the Elmbank was put hard to starboard. But before the helm had a chance to answer, the high cliffs were seen close by to starboard and the ship was felt to bump three or four times on the ground. She did not stop and followed the directions of the tug which by that time was well out on the port-beam. While the tug and her charge were in this position, the crew of the Elmbank seem to have got into a panic and kept shouting for the tug to come alongside to take them off as they thought their ship was going to sink. The foc’sle head bell was rapidly rung and other urgent signals made. The master of the tug then cast off the tow-rope, and manoeuvred his vessel until he got a 4-inch rope close under the stern of his charge to act as a breeches buoy with the view to saving life. The master of the Elmbank then asked the tug skipper to come alongside and take off his wife and two children. The latter replied saying he could not go alongside, but would take them on board if they were sent in the ship’s boat. The gig on the starboard side was then lowered, and the mate with four hands transferred the above passengers to the safety of the tug.

That operation occupied about an hour and a half. The Elmbank’s bilges were sounded but found to be dry. There was considerable conflict of evidence as to the state of the weather and the sea at the time. But with regard to the sea state, the Court reached the conclusion that with the wind at SE, it could not have been as heavy as the witnesses from the tug said it was.

Shortly after the gig had returned from the tug, the master of the Elmbank informed the tug skipper that he had slipped the tow rope as it prevented him from steering, and as the 4-inch and 5- inch lines to which the tug had been attached had parted, he offered the tug skipper a 7½-inch coir line. There was a rocket apparatus on board, but on account of the bad weather, as well as the position and condition of the ship he could not use it. From about 10.45pm until midnight, the Elmbank was kept heading to the WNW under a fore-topmast staysail while drifting at between three and four knots. At midnight the tug came within hailing distance and advised the Elmbank’s master to set more sail, steer NE by N, and run up the Firth.

The four lower staysails and the reefed jigger sail were then set and the course maintained until about 1a.m. At that time the tug skipper again advised Captain Greig to set more sail but this was not done and the Elmbank continued drifting to leeward. The wind and sea from the SSE kept gradually increasing while the weather became thicker. At 6am the Pladda Light was seen about a point on the port bow. The tug came in again within hailing distance, and once again recommended that Captain Greig should set more sail and try and weather Pladda. But on seeing that this was impossible, the latter asked the tug to take a rope and pull his stern round so that he could keep away from the land.

Owing to the severity of the weather this request was also refused. An attempt was then made to run up the jib, but in seeing that she only payed off a point, the master of the Elmbank hauled her up to the wind. The land at that time was close to the lee side. Both anchors were let go immediately and 70 fathoms of chain were paid out, but the anchors did not hold. Within just a few minutes the Elmbank drove ashore on the rocks near Bennan Head about two miles west of Pladda Light. Soon afterwards one of the lifeboats was lowered, all hands took to it and succeeded in effecting a landing just inside where the vessel lay. At about this time the tug lost sight of the Elmbank in a snowshower, when it was observed that she was ashore they proceeded to Kildonan for the lifeboat, but on their return found that the lifeboat’s services were not required. In the matter of a formal Investigation held at Glasgow The Court, having carefully inquired into the circumstances attending the above-mentioned shipping casualty, finds, for the reasons stated in the annex hereto, that the ultimate cause of the stranding of the Elmbank was due to the failure of the master, Mr. Alexander Greig, to set sufficient canvas to keep his vessel from driving to leeward after she became detached from the tug. The Court therefore finds him in default and suspends his certificate numbered 02260 for a period of six months from this date. The Court also censures Mr. Charles Morrison, master of the tug Hercules.

Dated this seventh day of February 1894.

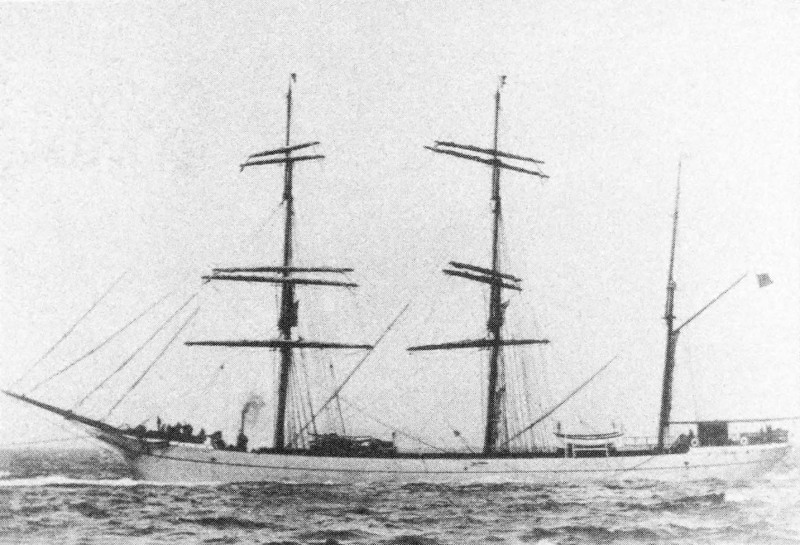

River Falloch

In 1891 six more ships of sail were to join the Andrew Weir Company. From William Denny of Glasgow came the 1,637 gross ton river Falloch, a ship built by Joseph Russell at Port Glasgow in 1884. The ship which is described as being an ‘iron clipper’ was named after a river that flowed into Loch Lomond. Although little in the way of the ship’s history under the ownership of Andrew Weir is known, her maiden voyage for William Denny was one of frightening proportions; the story was given by her master Captain J Davidson.

From the Otago Times June 1895:

Under the command of Captain J. Davidson the River Falloch left Glasgow on 2nd November 1884. She was on her maiden voyage with general cargo for Port Jackson, Australia, and was expected to arrive there sometime in January or February 1885. The ship rigged with a full crew the River Falloch proved to be a fast ship and was soon in the Bay of Biscay, but that is where the speedy ship was slowed down, both by head winds and heavy seas as far as the Azores. The heavy weather increased and the South Easterly hurricane force winds battered the ship. As a result the foremast which snapped at the deck came down and took with it the head gear and the main topmast as well as the mizzen topmast. In their efforts to secure the ship John McInnes was lost overboard and Edward Allison was killed. Another sailor had his arm broken while the bosun and an ordinary seaman who’d been aloft were injured. In that incident the bosun had slipped while he was 90 foot up in the rigging, but as he was falling to the deck the ordinary seaman grabbed him and hung on until assistance arrived. Only the lower mainmast and the mizzen lower mast with its crojack were left standing. After the hurricane had abated the decks were cleared and the ship was jury rigged. Captain Davidson tended to those injured and while the ship was still pitching and rolling quite heavily, he re-set the injured sailor’s broken bones before the River Falloch struggled into Funchal, Madeira. The body of Mr Allison was buried at sea and Funchal was reached on 26th December after a dreadful Christmas. After a cable had been sent to the owners regarding the ship’s encounter with the weather, and the fact that she was completely disabled, the tug Storm Cock was dispatched from the Clyde to tow her back to Joseph Russell, her builder, for repairs. The tow which began on 5th January 1885 took eleven days and repairs to the ship nine weeks. On 21st March 1885 the River Falloch resumed her passage to Port Jackson where she arrived in June.

When Andrew Weir bought the river Falloch in 1891 he had her cut down to a barque to reduce her crew numbers. However, the ship is reported to have sailed from Glasgow on 4th April 1895, with Captain David Young in command and a complement of 29. Amongst that figure of 29 were a first, second and third mate as well as 6 apprentices. But when she left Liverpool on 10th March 1897 with Captain Young still in command, his complement had been reduced to 22 with just a first mate and no apprentices. The river Falloch stayed with the company until 1909 when she was sold to Sigurd Bruusgaard of Drammen, Norway, who renamed her Avenir. In 1916 she went under the Italian flag and was registered at Genoa but was broken up at her home port in 1922.

Thistlebank

This was the largest of three sisters at 2,430 grt and Captain J. Wilson was her master on the maiden voyage. The ship was sold to E. Monson of Tvedestrand in 1914, but in the following year under Captain J. Forby Olsen she was sunk off Fastnet by a U boat on 30th June 1915 while on passage Bahia to Queenstown. The following story however, relates to a first trip apprentice named Michael Murphy from Hull who was nick named ‘Kick.’ He joined the Thistlebank at Barry Docks South Wales for her second voyage in July 1892. The Thistlebank was expected to make a twelve month voyage. She was a steel hulled sailing barque which had been launched by Russell & Company at Port Glasgow in the previous year. The ship left Barry on 21st July 1892 with the first leg of the voyage being to Cape Town with Welsh coal. After about a month the ship approached the equator, and, of course, the crossing of The Line as it is called. It was one of those rites of passage that had to be observed as Kick and his companions discovered. Afterwards, he described the events quite graphically in a letter home to his family. On the night of the crossing two men got dressed up, one as Father Neptune the other as his wife named Trident. They were dressed in oakum wig and whiskers with a large tin can that was cut into a crown. They also had the barbers with them. They pretended to come aboard from over the side and shouted out. “Ship ahoy” they then rigged a platform and a large tub of water with lighted lanterns all round it. The three apprentices, the sail maker and two ordinary seamen were to have our heads shaved as we had never crossed The Line before. We shook hands with Father Neptune and his so called wife, then sat on the edge of the tub to be lathered with grease, Stockholm tar and droppings from Denis the pig. It was then scraped off with a big wooden knife and daubed on our heads. We were then put into the tub with all our clothes on and wet through with buckets of, water, but we were all right again next morning except for being a little greasy and some extra dhobying to do on washing day. Young Kick wrote home regularly to his family on his voyage, and his letters provide a vivid description of various aspects of life at sea under sail in the late nineteenth century.

His letters are often full with talk about food: When we are at sea we get coffee every other morning. Breakfast consists of hard tack biscuits, butter, salt beef or salt pork. At tea we get hard tack biscuits, milk-less and sugar-less tea, butter and all the meat left-overs which is chopped up small with saute potatoes and fried in fat. Friday’s is known as being ‘Catholic Day’ when no meat is given and salt fish is served. On Sundays we get fresh tinned mutton soup, potatoes, barley and a loaf of soft bread. I miss the puddings but I make them myself when we are in port.’

He also provides some interesting accounts of places the ship calls at and writes:

Cape Town is a splendid place situated on a fine harbour with mountains in the background with one of them being the celebrated Table Mountain. There are fine buildings, a palace, castle, batteries and gun boats. I have never seen such a nice place. There is a breakwater about ½ a mile long on which the convicts who are under guard have to work to make it larger. Table Mountain is covered by clouds most of the time, but it is a grand scene to see on a calm day, the houses in the sunshine are all white. The bay is like a pond and on in the other side of the bay the mountains run right along the coast of Africa. On a clear day we can see the smoke rising from native villages behind the mountains. The Thistlebank was originally expected to sail from Cape Town to Chittagong in India, but the orders were changed, and instead, the vessel headed for Newcastle, New South Wales. What had been expected to be a year’s voyage looks like turning into one of around eighteen months.

Although Kick was disappointed at the prospect of spending his next birthday away from home he did look forward to the extra money his trip would bring him, the time he was at sea learning to becoming a more accomplished seaman, and the gaining of experience in what the oceans of the world could throw at a ship.

Dear Father and Mother, we left Cape Town on Saturday November 12th and have had fair winds all the way. The ship is going twelve, thirteen and sometimes fourteen knots. All the time we had one day of calm. They call it Running’ the Easting Down. We arrived safe in Newcastle on Monday 19th December. After having had a very stormy passage, the ship was rolling so much, that it rolled us out of our bunks and the chests went sliding from one side of the cabin to the other and broke from their lashings. On the 1st December at about 1am in the morning the ship was struck by a heavy squall. We had just got turned in at 12pm till four when at 1 o’clock orders were shouted out for us to clear the royals, let go the topgallant and top sail halyards and clear the lower to the t’gallant sails up. All hands had to turn to and shorten sail. The royals were blown into ribbons before we could take them in, and all the ropes belonging to it carried away. I went to the main royal to help make it fast when it hit me and skinned my nose. We had another squall on 7th December but it done no damage.

As a later letter shows, that voyage proved to be more eventful than he at first told his parents.

When we were about two weeks out of Cape Town I was struck by a sea that washed me down the deck and into some iron stanchions which laid me up for three weeks. I couldn’t move for the first week. I was bandaged up and as white as a sheet. I was still laid up when we entered Newcastle, but I started work 4 days after and was soon as well as ever. ‘Dad wanted to know if I could take the wheel. ‘I was at the wheel every night and he (the captain) let me take the wheel in the day time.’

After an extended stay in New South Wales, the Thistlebank sailed across the Pacific Ocean and reached San Diego in California towards the end of April 1893. Because of long periods of fine weather that passage had taken ninety three days instead of the expected and hoped for fifty. On the ship’s arrival the people there were somewhat surprised.

It seems that we were so long on the passage that we had been posted missing and reported as being lost. After a few weeks in San Diego we sailed to Iquique in Chile where we arrived after a very long passage of 78 days in August 1893. Here I met up with around six of my school mates on other ships whilst the vessel was loading a salt petre cargo for Hamburg.

He was less than impressed with Iquique and no doubt pleased when the Thistlebank finally sailed for Hamburg. However, the transportation of saltpetre from Chile to Europe in the late nineteenth century is by way of Cape Horn, and that was considered to be one of the hardest of passages. Nitrates were in great demand in the nineteenth century, both as a means of improving soil and also for the munitions industry. Ships sailing from Chile to Europe covered over 7,000 miles and usually took over 100- 120 days but sometimes an awful lot longer. Certainly Kick’s passage to Germany was not without its problems as he outlined in a letter to his parents in January 1894:

We have arrived all safe in Hamburg after having had a very hard passage of 122 days. Everything went well until Christmas when we had heavy gales. But then the provisions ran out and we had to live on maggoty biscuits and salt beef. When we reached Deal we only had one day’s supply of beef left on board. We have been nearly starved on this passage, and our half-deck house has been flooded on a number of occasions. Chests were full and clothes soaked through. I hadn’t had a dry change in 2 weeks. Sometimes we could not get along the deck for our dinner because there was so much water coming aboard.

By then Kick was still only seventeen years old, but he had worked his way around the world on a four masted sailing ship. Whilst the ship was laid up in Hamburg, young Kick was able to take some leave and snatch a few weeks back home with his family down Bluebell Entry in Hull. He had been away for more than eighteen months. Back in Hamburg at the end of March, Kick sailed once more for the Pacific ports and arrived at Santa Rosalia, California in August 1894. He described it as a fine passage of 171 days at sea. He was enjoying his time at sea but missing his family and friends and the Hull Fairground.

Dear father and mother, I am just as happy here as when I am at home, but often wish I could have a night off to go to Hull Fairground. This is the third time I have missed it. We are still in the best of health and are having pretty good times, going for picnics with the captain and his wife. I wish you would write a little oftener as all the other chaps are getting letters every time the steamer comes in, and I have only had two, one when we arrived, which was written on 25th July, and another 3 weeks after.

Castlebank

The Thistlebank later moved up the coast to Portland in Oregon and did not make the return voyage to Europe until late in the spring of 1895. Much of that was due to crew desertions in America. This time the ship went to Queenstown. Kick and his ship arrived in Ireland in august 1895 after a 142 day passage after which the ship made its way to Liverpool from where Kick seems to have been able to grab a few days leave at home. At this stage Andrew Weir & Company transferred Kick and a number of other crew members to another of the company’s ships named Castlebank, a somewhat smaller three masted sailing vessel which was laying at Rotterdam. He passed through Hull en route for Rotterdam, and snatched what proved to be his last brief stay with his family. His new ship was not without problems and had to turn back to Rotterdam on a couple of occasions, after experiencing difficulties with stability which worried both captain and crew. Later on the Castlebank ran aground and had to be towed off. Nevertheless, the problems were eventually overcome and the ship made a decent 120 day passage to Port Germain in Australia. Kick writes:

We have been exactly 120 days on the passage, and it has been the finest passage we have had. A bit slow but fine weather all the way and not a gale of wind at any time. I must tell you that we have got ourselves into a floating hotel on this ship. We have had plum pudding, beef pies, Rice puddings, fish, and nearly every mortal thing we could ask for. We have had as much as ever we could possibly eat. And the captain is such a nice man, he comes into our half-deck house and plays games with us and spins yarns nearly every night. The first night he went ashore he brought us back as many grapes as we could eat.

The Castlebank sailed around the Australian coast to Newcastle NSW where a cargo of coal was loaded. Kick and his half-deck companions seem to have thoroughly enjoyed an almost three month sojourn before leaving in September 1896 for Valparaiso. But when that ship sailed it was the last that was ever heard of the Castlebank, Kick Murphy or indeed the rest of the crew. The vessel was reported missing. The loss was never explained, and indeed, it was one of those perennial mysteries of the sea. The weather in the Pacific at that time was reported to have been good on the passage she took. It was thought at the time that the cargo of coal must have possibly caught fire and the crew had taken to the boats. There was hope for some time that they might have been picked up by a passing ship. But days passed into weeks and then into months with still no news of the ship and all hopes for the crew dissolved.

A friend of Kick’s in Australia, Maggie gray, wrote a final letter to his family in Hull in April 1897:

I received your kind letter on Saturday and I’m very sorry that I have to tell you, that it is only too true about the loss of the Castlebank, and I fear all hands. I have made every inquiry but nothing has been seen or heard tell of her since she left here five months ago. But I can tell you that your son left here in the best of spirits and seemed to be very happy all the time he was in port. He was the third mate and was liked by everybody on board as well as on shore where he had a lot of friends. He was up at our house just the night before the ship sailed with a few of his friends to wish us goodbye and we are indeed very sorry to hear of your loss as I know he was indeed a good boy and I am sure he would have prospered in life with all his undertakings.

Michael (Kick) Murphy was one of many Hull people who lost their lives whilst going about their business in great waters, but although his life was cut painfully short, his few years at home and afloat were filled with interest and adventure. He had seen much more of the world in his short seagoing career than many others can manage in a lifetime. As for his family, well they seem to have lived on for some time in Hull’s old Town. His mother, Fanny, died in 1915 while his father Michael followed her within two years aged 75.

Kick’s first ship, the Thistlebank was sold by Andrew Weir & Company to E. Monsen & Company of Norway in July 1914. But she was sunk by the German U-boat, U-24, off Fastnet rock on the Irish coast on the 30th June 1915. Michael Murphy has no memorial, save his beloved Hull City FC and Hull Kingston rovers, whenever he could he eagerly read every inch of the newspapers his family sent him from home.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item