Memories of years ago show that stirring from the deep and usually dreamless sleep of ‘the watch below’ was either from a crew member’s insistent efforts to put me ‘on the shake’ for yet another watch on the bridge at some ungodly hour, or by the sudden eerie silence in the dead of night when the main engines stopped without warning, at which time all on board were soon awakened! In such circumstances, instant recall of any dream was effectively nil, until that is, later reversion to landlubber status.

Recently, I was jarred to wakefulness in the comfort of my own bed just at the point at which my ship in convoy was being torpedoed. This seemed strange, as I was in fact a ‘Baby Boomer’ – a member of the ‘post-war bulge’!

With memory later restored, it was only days before, during the summer of 2015, when by happenstance I had fallen into conversation on the berthing pontoons at the confluence of the Rivers Kelvin and Clyde at Pointhouse, with Calum, skipper of the small passenger vessel Ellen’s Isle of the Govan Ferry free-to-all ‘summer only’ service. As a hitherto lifelong trawlerman of Eriskay, South Uist, Calum was as good for ‘a yarn’ as any seafarer. His story on this occasion referred to another seaman who, had he lived, would in time, have been his uncle.

The details of his relative’s wartime demise, possibly with a little lost in the telling by successive generations of family, seemed sketchy with the vessel in question, Empire Moat, supposedly an ocean going tanker, a unit of a convoy to Gibraltar, torpedoed and sunk in the night, but with all on board rescued by the Union Castle liner Balmoral Castle. By further misfortune however, the rescuing vessel had been bombed later by a German aircraft, with the loss of five Empire Moat crew including Calum’s 21 year old Able Bodied seaman relative, Malcolm.

Never one to ignore the prospect of an intriguing story, I determined to further research the circumstances and clarify the details of Malcolm’s loss, if for no other reason to, in today’s parlance, provide closure for the family. What transpired however in my research was rather different to Skipper Calum’s earlier perceptions.

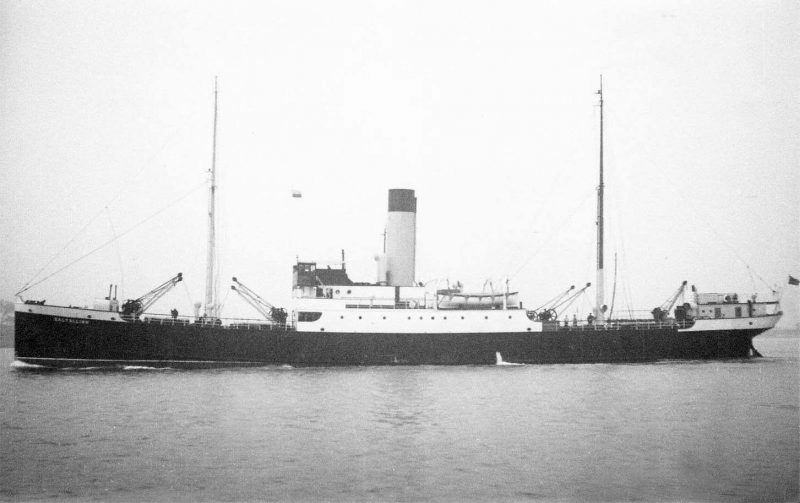

As it turned out, Empire Moat was not an ocean going tanker. Rather, she was a more modest 2,922 gross ton general purpose coal burning tramp type steamer of the WW2 War Standard “Scandinavian” design. Whilst bearing a remarkable resemblance to Lambert Brothers’ 1937 Lithgows built 2,318 grt steamer Terlings, the origins of the Scandinavians’ design reputedly stem from the drawing boards of Wm. Gray & Co., of West Hartlepool. Grays completed a total of 24 Government Ministry of Shipping (from 1940, The Ministry of War Transport) ordered examples of the class between 1940 and 1944 with five other UK yards completing a further 14 units to Government order between 1941 and 1946. This included Wm. Lithgow of Port Glasgow who built Empire Moat, the second of four units constructed by them during 1941. Following completion during July, she was passed to the management of Watts, Watts & Co, of London.

On 20th September 1941 whilst in convoy OG-74, Empire Moat was in ballast on a voyage from London (via Oban for convoy assembly) to Gibraltar when, in DR position 48.07N, 22.05E (NNE of the Azores) at 2321 hours, the German U-124 commanded by Korvettenkapitan Johann Mohr, fired three torpedoes at two minute intervals towards the convoy. The U-boat had initially thought that they had struck a tanker, but later discovered that they had sunk both Empire Moat and another British flag vessel, the United Baltic Corporation’s 1,303 grt London registered, 1920 Troon built, short sea trader Baltallin (ex Starling of the General Steam Navigation Ltd.), also destined for Gibraltar, with a cargo of Government stores.

All of Empire Moat’s crew including Master, 28 crew and 3 gunners survived this attack and were picked up by the Scapa Flow based convoy rescue ship, Union Castle’s European ports feeder vessel, the 906 grt M.V. Walmer Castle (Harland & Wolff, Belfast 1936), rather than the previously imagined Balmoral Castle. Baltallin’s crew was not so fortunate, losing 7 of her complement of 35 in the sinking, with survivors also picked up by Walmer Castle plus the escorting Flower Class corvette HMS Marigold (K87).

The following day, whilst in position 47.16N, 22.25W, Walmer Castle was attacked and bombed by a German FW200 aircraft, catching fire and sustaining damage so severe that she was later scuttled and sunk by the gunfire of her naval escort. Tragically, five of Empire Moat’s crew including (A.B.) Malcolm and 11 of Baltallin’s hitherto surviving crew were to lose their lives in the attack. Empire Moat’s remaining crew of 27 and Baltallin’s 17 were rescued by HMS Marigold and the sloop HMS Deptford and landed at Gibraltar on 28th September.

I have always considered that point at which the apprentices, cadets and the supposed rather more upper class ‘midshipmen’ of our Merchant Service of some 50 years ago, complete their then mandatory 36 months’ (foreign going) sea time, (less any remission earned via a formal nautical school pre sea cadet training course), to be not only that when chipping hammers and paintbrushes can at last be discarded (or otherwise gleefully thrown ‘over the wall’) in the firm knowledge that they should with optimism, never again be routinely required, to be also a time of celebration, as exit from that ‘lowest form of animal life’ status aboard ship. A time to return to the delights of home for other than fleeting voyage leave taking and perhaps whilst also attempting study, to take up again with that (ex) girlfriend or even a new one, prior to finally submitting in great hopes to the rigours of the Second Mates ‘Ticket’. A time for old nautical school friendships to be renewed or indeed just the opportunity to mix with like-minded classmates to swap salt sprinkled lies and yarns recounting the hardships of our essentially carefree but seemingly enslaved apprenticeships. These were the times at which we might ‘imbibe’ in a lunchtime refreshment or two with colleagues, invariably resulting in those post prandial remonstrations on the part of our afternoon lecturer, that liquid lunches never lead to early resolution of the mysteries of the PZX triangle!!

Such may have been the circumstances for a now retired shipmaster acquaintance of mine, an ex Irish Shipping apprentice much experienced on their tramps, liners and oil tankers who, after being informed by his examiner that he had passed Second Mates, found himself ‘broke’….. utterly broke!

In penury therefore, his sole course of action had to be an immediate visit to the Dublin Shipping Office when, upon enquiring with the desk clerk, was in short order approached by the Master of the Newport, Monmouthshire registered Uskside, due to sail on the evening tide and urgently seeking the services of a Third Mate. Without hesitation, Uskside had another signed on addition to her complement.

Upon joining his first ship as a ‘proper officer’, my friend found himself aboard a somewhat rudimentary sixteen year old 2,961 grt UK War Standard “Scandinavian” general purpose steam tramp. Laid down during late 1945 and launched on 21st March 1946 at Troon’s Ailsa Shipyard as Empire Warner (the very last example of the class for the MoWT), she had been bought whilst fitting out by Richard W. Jones’ Uskside Shipping Company who renamed her Uskside.

Fulfilling what they were built for in all simplicity, Uskside and her like navigated the oceans of the world without what could be described as the ‘fancy gadgets’ to be found aboard almost all merchant ships today. Our tramp, together with her two identical “Scandinavian” sisters in the fleet, now with oil fired boilers converted from the original coal fuel during 1952, (permitting increased deadweight of some 350 tons and reduced engine room hands) fed her NE Marine designed triple expansion engine to push her along on a good day at a maximum of 10 knots. On the starboard hand of her engine room was a small steam driven generator producing a low 110v DC output to feed domestic lighting (one light bulb per cabin) and the charger for the radio room batteries.

One other electronic gadget was to be found on board, in the form of a single loop RDF, turned by hand from inside the wheelhouse, but powered by a remote battery. The receiving set however appeared to be utilised more to listen to Radio Luxembourg rather than for true navigational purposes. On the Monkey Island was to be found the ship’s magnetic standard compass with a similar magnetic steering compass in the wheelhouse immediately ahead of the large wooden wheel. Steering was by rod and chain leading to the steam driven steering gear down aft in the tiller flat. The wheelhouse also contained one large brass chain operated telegraph, speaking tubes to the Master’s cabin and engineroom and a lanyard to the steam whistle on the funnel. As explained by the Master, in the small ‘cupboard’ abaft the wheelhouse designated the chartroom, was contained a paper fed sounding machine which, as a prototype, had been installed during the vessel’s construction, but had never worked. No subsequent examples of the model were produced. It remained a mystery to all therefore why it had not been removed, particularly as it was no longer connected to the ship’s electrical supply. Soundings when required were taken from the foredeck by use of the traditional lead line and tallow.

Whilst the ship’s boilers were oil fed, the galley range continued to be coal fired, resulting from time to time, particularly when loading a South Wales coal cargo, in one truckful being tipped into the galley bunkers, immediately opposite the Third mate’s cabin. As often occurred, the cook, forgetting to close the hatch to his bunker and swearing volubly, found his latest soup iteration now covered in a not too fine layer of coal dust. On querying if the Third Mate was going to dine aboard and being answered in the negative, the cook would reply, “Ah well, they won’t know the difference”, whilst busily stirring the dust into the mixture. Further comment revealed that with his cooking, nobody would know the difference anyway

With minimalist crew accommodation, the ship’s ratings and PO’s were berthed aft, with officers amidships.

On the evening tide, Uskside duly departed her Alexandra Dock berth and whilst turning into the Liffey, the Old Man invited the Pilot below for a drink when he was ready. This illicited a prompt reply that he would come down directly, as he knew this young Irish Third Mate to be well enough acquainted with the river to take her out quite unaided.

Some days later, Uskside arrived at Casablanca and awaiting her berth from where she would load phosphates, had anchored out on the roads. At 0800 our Third Mate assumed his watch on the bridge, when some 10 minutes later the Master exited his cabin on the deck below, looked up and asked “What are you doing?” “Keeping an anchor watch, Sir” was the reply. “This ship has been anchoring here for many years and can look after herself. You just come down here and start scraping and varnishing this taffrail.” Like most of us ex-apprentices or cadets, we were all ‘dab hands’ at varnish work. Over a period of time, every bit of outside woodwork would be duly scraped and varnished. The ‘up’ side, according to my friend, was that as the ship sailed under “B” Articles, overtime was also paid to officers.

Some three years later, in March 1965 to be precise, and after several transfers to other units of the fleet, my friend found himself back aboard Uskside. With almost 5,000 tons of Moroccan phosphates in her holds, destined for Cork and in a position off the Portuguese Coast somewhat North of Lisbon, he mounted the bridge for his morning 8 -12 watch, to find dense fog with visibility around one cable.

With the telegraph indicating half ahead, the Old Man, anxiously peering over the bridge dodgers whilst listening out for fog horns other than his own, but hearing none, stated he was going below to the toilet. My friend gave a mandatory one long blast on the whistle and remaining on the starboard bridge wing, stared into the murk. Within moments, he saw what looked like a white wave, four points to starboard. It was a wave, a bow wave approaching at full speed. Diving into the wheelhouse calling “hard-a-starboard!” to the helmsman he rang down double full astern on the telegraph. Too late! Out of the fog emerged a black hulled general cargo ship and Uskside hit her with her bar stemmed bow on the stranger’s port side around #2 hatch. With bow crumpled and with the shock of the impact driving Uskside astern, the other vessel continued her course with her sole sign of life aboard appearing as someone running out on to the port bridge wing, tearing at his hair, before this unknown vessel once again disappeared into the fog. Uskside’s Master, still pulling up his trousers, quickly returned to the bridge. By the time his ship came to a full stop, her Yemeni firemen were on deck in lifejackets each with a bundle of belongings and quite ready to abandon ship.

By good fortune the collision bulkhead held, appeared undamaged and she was not taking water. In calm weather and with little more than a low oily swell, the Master opted to continue the voyage to Cork unaided. Collision bulkhead shored up and in spite of the protests of another officer who insisted upon diversion to the nearest port (Lisbon), the Master’s decision prevailed. When halfway across the Bay of Biscay, the weather deteriorated and a South Westerly gale sprang up, requiring the ship’s stern to be turned to wind. With a growing swell and labouring heavily, she shipped one big sea down her funnel but which luckily did not extinguish the boiler furnaces. With heaving to, head to wind not an option, Uskside continued in an easterly direction and rapidly closed the French coast. The Master, Mate and Third Mate as an expedient, began their search upon an ancient chart to identify an appropriate sandy beach upon which they could ground their damaged vessel. At the last minute however, the wind backed and moderated allowing them to claw away from the coast and resume passage to Cork.

Uskside arrived safely at Cork some days later, discharged her cargo and continued thereafter lightship to drydock at Cardiff for repairs. Now promoted, my friend opted to remain with the ship whilst she acquired a new all riveted bar stem bow. He recalled the duration of repairs to his fully decommissioned charge as particularly pleasant, during which time he ate with the workers in their yard canteen, drank with them in their pubs and danced with their daughters in the evening. Indeed manna from heaven for a hard worked second mate!

He recalls that no formal enquiry was undertaken as a result of the collision. Rather, he was required only to make a statement to the Company’s lawyers. It was later discovered that the errant vessel was a Greek and had sustained only a gash to the hull above the waterline.

In light of incidents such as Uskside’s described above and in full acknowledgement of the horrors of war as experienced by Empire Moat, Baltallin and later, convoy rescue vessel Walmer Castle, I do wonder just how many ex-bridge watch keepers, even those who have had no exposure to such incidents or emergencies, now wake in a cold sweat, at that jarring impact of a torpedo explosion, at response to the fo’c’sle lookout’s “breakers dead ahead!” call , or even that seemingly unkempt tramp out on the port bow which, with unchanged bearings, has blatantly ignored your five short blasts… “To sleep, perchance to dream!“

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item