Owned and Chartered Oil and Gas Tankers

The rise of the many independent Norwegian tanker owners such as Bergesen as well as Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos and similar Greek entrepreneurs in the 1950s and 1960s gave a rapid increase in the amount of available chartered tonnage for the oil majors. This was normal commercial practice but was increased or decreased to cover many emergencies such as the Suez Crisis of 1956 and the closure of the Suez Canal between 1967 and 1975, and the price hike by OPEC countries in October, 1973. The percentage of chartered in tonnage by the oil majors tanker fleets rose from 39% of the world tanker fleet in 1938 to 58% in 1960 and 60% in 1970 and 64% in 1980 to reach 73% in 1990 (Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy). This trend of minimal tanker ownership has continued with the current Exxon fleet of the United States of America having an almost fully chartered tanker fleet for 99% of their requirements with only five owned or leased tankers. This latter figure is due to the devastating oil spill of Exxon Valdez in Alaskan waters in 1989, and the strict OPA90 pollution laws that became a requirement in 1990 in the United States where it is much safer for the reputation and economics of an oil major such as Exxon to charter.

In the 1950s, there were seven oil majors known as the ‘Seven Sisters’ with Standard Oil of New Jersey (known as Exxon in the United States of America but Esso to the rest of the world), Standard Oil of New York or Mobil, Standard Oil of California known as Socal which later became Chevron, Gulf Oil, Texaco, BP and Shell. Today, due to mergers and takeovers, there are only four oil majors left in the European oil majors of BP and Shell, and Exxon and Chevron in the United States. The latter two companies are the biggest and second biggest suppliers of oil and energy in the United States of America. The third biggest supplier is an amalgamation of five American Oil Internationals in Conoco (Continental Oil), Phillips and Arco, the latter being a merger of the Atlantic Oil, Richfield Oil and Sinclair Oil companies. This has propelled these five smaller oil companies by market forces to merge into the status of an oil major.

When a requirement for an oil shipment or series of shipments is established it is usually offered by the oil major on the open market via a tanker broker to several leading independent tanker companies simultaneously by E-mail. The tanker broker acts as an intermediary answering all questions from both the charterer and the participating independent tanker owners regarding details of the shipment(s) i.e. port charges, loading and discharging details in particular relating to laytime, the number of days allowed for cargo transfers, and demurrage etc. When the participating independent owners have replies with their freight rate estimates, the broker acts as an agent between the charterer and the successful tanker owner until the fixture is concluded. The formal documentation regarding all details of voyage and cargo is known as a Charter Party, drawn up by the broker, and agreed to on a preliminary basis by both parties.

Oil cargoes are not traded on the Baltic Exchange in London and other major bourses, but are handled by six private brokering firms in London for most international oil cargoes and a similar number in New York for American oil cargoes. However, the principle of ‘Our Word, Our Bond’ remains the same, with the full Charter Party often signed during or after the completion of the voyage (s). The Charter Party can take three forms :-

A Voyage Charter is an agreement for the carriage of oil from one port to another, the tanker owner receiving freight money at a fixed sum per day for the cargo carried. It includes all of the details and terms under which the oil is carried, the ports and the dates between which loading is to commence and lay-time maximums, demurrage etc. The shipowner pays for the port charges, fuel costs, wages of the crew and the maintenance of the ship.

Under a Time Charter, the shipowner hires out his tanker for a period of time at a fixed sum per month based on the deadweight (dwt) carrying capacity of the vessel. The charterer decides the ports to which the tanker takes the oil cargoes. The shipowner contracts to provide a seaworthy vessel capable of maintaining a stated speed on a given consumption of fuel. The charterer pays the whole cost of running the tanker as regards bunker fuel, loading and discharging costs and port charges. Under a Bare-Boat Charter, the charterer has the added responsibility of paying for the maintenance and all other charges of the tanker as if he were the owner.

All of the oil majors pride themselves on their strict Vetting and Inspecting procedures for chartered tankers in order to root out the really substandard tonnage that is put forward for charter. However, none of these procedures are foolproof, as I remember the case of a tanker that was passed by an oil major inspector as ‘completely safe in all respects’ only for it to sink off Malta the very next day en-route from Italy to Libya to load cargo. The fallout after a devastating pollution incident of an owned tanker of an oil major can be huge in legal compensation claims, and a serious fall in its reputation and share price. For these reasons, a culture of anonymity has grown up where all previous oil major tanker funnel colours and naming systems have been obliterated, except in the case of the British Petroleum (BP) and Shell fleets with their very high safety records. The chartered tanker offers a further measure of anonymity, improvements in planning for other capital intensive projects, and the avoidance of tying up of capital in expensive double hull tankers. This release of capital is much more likely to be productively used for the increasingly difficult and expensive exploration for new oilfields in remote parts of the world.

Worst Pollution Disasters

The twenty worst tanker oil spills in the world polluted the seas and coastlines of the world with two and one half million tonnes of oil, enough to wipe out most of the seabirds and marine and shoreline creatures in the affected areas. This is roughly twice as much oil as spewed out of the deepsea Macondo oil well after the Deepwater Horizon rig blew up in the U.S. Gulf in 2010. Seventeen of these disasters that spilled more than 50,000 tonnes of oil were caused by chartered single hull tankers. The first serious tanker pollution occurred with the grounding of the tanker Torrey Canyon of 120,000 dwt owned by a Los Angeles company and bareboat chartered to the Union Oil Company of California, but registered under a Bermudan company and flying the ‘Flag of Convenience’ of Liberia. She ran aground at full speed in broad daylight on the Seven Stones Rock near the Isles of Scilly on 18th March 1967. She was badly holed in her middle tanks as she was impaled by a huge rock and a Dutch tug could not refloat her during the first 24 hours when 20,000 tons of crude oil had escaped. Refloating attempts were abandoned on 29th March after the tanker had broken in two four days earlier. The British Government then took the unusual step of bombing the two halves first with paraffin and then with high explosives, but these mostly missed their target and burnt little of the remaining cargo. In Cornwall, massive pollution had occurred to a long length of coastline to the north and east of Land’s End and the summer tourist trade had been completely ruined, with further widespread pollution in Guernsey on 7th April. An estimated destruction of 100,000 seabirds took place, but no international liability conventions were in place at this time and the tanker owner went unpunished financially.

The 214,861dwt Exxon Valdez was built in 1986 by National Steel at San Diego. On 24th March 1989 she struck Prince William Sound’s Bligh Reef and spilled 10.8 million US gallons of crude oil.

The Shell ‘M’ class VLCC Metula was the first oil major owned giant tanker to contribute to this huge pollution total when she ran aground in the Strait of Magellan on 9th August 1974 during a voyage from Ras Tanura to Quintero Bay in Chile. After part of her cargo had been spilled and part discharged to lighten her she was refloated and anchored in the Bay of Angra dos Reis on 29th November 1974. Here the rest of the cargo was transferred to other tankers, but Metula was beyond economical repair and left there on 25th January 1976 in tow for Santander via Brunsbuttel for demolition. She was briefly aground at Santander due to her huge size in the narrow channel, but under the name of Tula she was refloated and moored at the scrapyard. Shell had taken the decision to order the new technology of the ‘M’ class VLCC prior to the onset of the Six Day War of 1967 and the closure of the Suez Canal, thus adding a huge amount of sailing time around the Cape of Good Hope to the Persian Gulf and dramatically reducing the number of voyages each year per ship.

The next huge spill was one of 220,000 tons of crude oil with the grounding of the VLCC Amoco Cadiz, built in Spain in 1973, and owned by the giant Amoco oil company, which was taken over by oil major BP in December 1998. She ran aground on rocks three miles from the shore of the Brest peninsula near the village of Portsall after encountering steering gear trouble in the English Channel on 16th March 1978. The vast majority of her huge crude oil cargo poured quickly from her many ruptured tanks, swamping the French coast with two or three feet deep pollution all along the Brittany coast from Ushant in the west to Vierge in the east. During the night of 28th March, the wreck broke into three sections to allow the remaining crude oil to add further to the 130 miles of polluted shoreline and increase the oil slicks in the Channel to an estimated 1,900 square miles. The French Government claimed $300 million in cleanup costs from the Chicago office of Amoco, and many claims were lodged from fishermen and French oyster and shellfish farmers. In July 1990, a judgment of $128 million was obtained against Amoco for this damage to the wild and beautiful heritage coast of Brittany.

The other huge spillage from a giant single hulled tanker owned by an oil major was that of the Exxon Valdez in the pristine waters of Prince William Sound in Alaska on 24th March 1989. Under Capt. Joseph Hazelwood, she got no further than 22 miles down Prince William Sound from her loading terminal when she ran aground on Bligh Reef and caused enormous damage to this most environmentally sensitive area. It is home to whales and marine creatures of all kinds and is a nature lover’s paradise, which was quickly transformed by the 36,000 tons (11 million gallons) of crude oil spilt with heavy damage to birdlife and wildlife as well as to the local economy. Claimants from the many ruined businesses operating in and around these former pristine waters as well as Alaska State claims amounted to $5.3 billion including $287 million in immediate compensation to fishermen who could no longer work. Exxon was clearly to blame and was keen to be seen using the latest boom and skimmer technology to contain the pollution. The draconian OPA90 Oil Spill Pollution Acts were quickly voted in by the American Congress in the following year of 1990. The legislation liabilities are severe and go together with the refusal to allow any single hull tanker nearer to an American coast than 60 miles by the year 2010. Thus, chartered tankers have to be double hulled and double bottomed in order to be allowed to carry oil today to America as they give the best defence against this type of appalling pollution and subsequent expensive clean-up. Exxon Valdez after refloating arrived at the San Diego yard of her builders, National Steel and Shipbuilding Company for rebuilding and was renamed S/R Mediterranean to operate in European waters and frequently unloaded crude at Fawley. She was beached at Alang in India on 2nd August 2012 under the name of Oriental Nicety for scrapping.

Worst Casualty Period

This is, of course, excluding wartime or as a result of having to run the gauntlet of warring nations e.g. in the Persian Gulf between 1981 and 1988 to load cargo. It is not also, as you might think, the period when the ‘new technology’ Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC) was exploding in ballast when tank cleaning. Shell suffered most in this respect when the brand new Marpessa of their 22 tanker strong ‘M’ class exploded on her maiden voyage on 12th December 1969 in which two Chinese crew members died. She sank stern first 110 miles north of Dakar, and the British flagged fully loaded Shell tanker Serenia on her way home was able to take off the remainder of the crew and land them at Dakar for repatriation.

Mactra next suffered the same type of explosion in her cathedral like tanks in ballast fifteen days later whilst tank cleaning off South Africa and arrived at Beira on New Years Day and moved on to Durban for temporary repairs. In October 1970, she arrived at Yokohama to have a new forepart built on and she re-entered service in March 1971.

A third new chartered VLCC, Kong Haakon VII, also blew up on 29th December 1969 while tank cleaning and the resulting fire destroyed her. Something was very wrong with these giant tankers, and inert gas systems were then introduced to make tank cleaning of a VLCC a safer operation, and later Crude Oil Washing (COW) was introduced to remove the built up residues that form in the extremities of big tanks.

The period with the highest tanker casualty record was ten years later during the fifteen month period between 1st January 1979 and the end of March 1980. The London Salvage Association reported no less than thirty five cases of explosions and fires on tankers and ore/oil carriers.

On the first day of this period, the Goulandris owned Greek VLCC of 215,212 dwt, Andros Patria, blew up after a crack had appeared in her hull ‘midships. Some 26 crew members died when their lifeboat overturned in heavy seas, but three crew were saved from the deck of the tanker. She was off Cape Finisterre when the explosion happened while on a voyage from Kharg Island to Europoort with crude oil. She was taken in tow by the tugs Poolzee and Typhoon and towed to various anchorages where over 90,000 tonnes of her cargo was offloaded to other tankers. She left Lisbon in tow for Barcelona on 12th June 1979 to be broken up.

An even bigger disaster occurred at Whiddy Island, Bantry Bay a week later on 8th January 1979 when the Compagnie Navale de Petroles of Paris tanker Betelgeuse of 121,430 dwt blew up at her berth while unloading and broke in two killing 42 crew and seven terminal workers. There were between 40,000 and 50,000 tonnes of her 120,000 tonne cargo still on board when the explosions took place.

On 20th March, 1979, the Soponata of Portugal VLCC of 323,114 dwt, Neiva, caught fire in her engine room while unloading at Antifer fortunately without loss of life. She had been completed at Gothenburg in November 1976 as the first of the Soponata ‘N’ class, and was later rebuilt with new cargo pumps at Bahrein. The Greek owned tanker Atlas Titan of 213,000 dwt owned by Centurion Maritime S.A., Liberia next exploded on 27th May 1979 while cleaning her tanks at Setubal near Lisbon, sadly four crew members died in the subsequent fire.

The largest oil spill in history from a tanker occurred on 20th July 1979 when two Greek independently owned tankers collided in the Caribbean with the Livanos owned Atlantic Empress spilling all of her 257,000 tons of crude oil. Publicity was minimal as the Press were not able to contact these elusive and anonymous tanker owners in the same way that they can contact the offices of the oil majors. Atlantic Empress was on a voyage from Jebel Dhanna in the Persian Gulf to Beaumont in Texas with a cargo of naphthalene when she collided with the Greek VLCC Aegean Captain (ex Marisa of Shell), owned by Coulouthros, off the coast of Tobago, the latter ship having sailed from Curacao. Fire broke out forward on Aegean Captain but was later extinguished, but Atlantic Empress was gutted by fire and 29 of her crew of 39 sadly lost their lives. The massive pollution from the release of her cargo stretched all the way from the collision location to the point 300 miles east of Barbados to which the constantly burning and exploding Atlantic Empress was towed and then scuttled. Aegean Captain was towed back to Bullen Bay for tank cleaning and then to St. Michael’s Bay, but was later sold for breaking up in Taiwan.

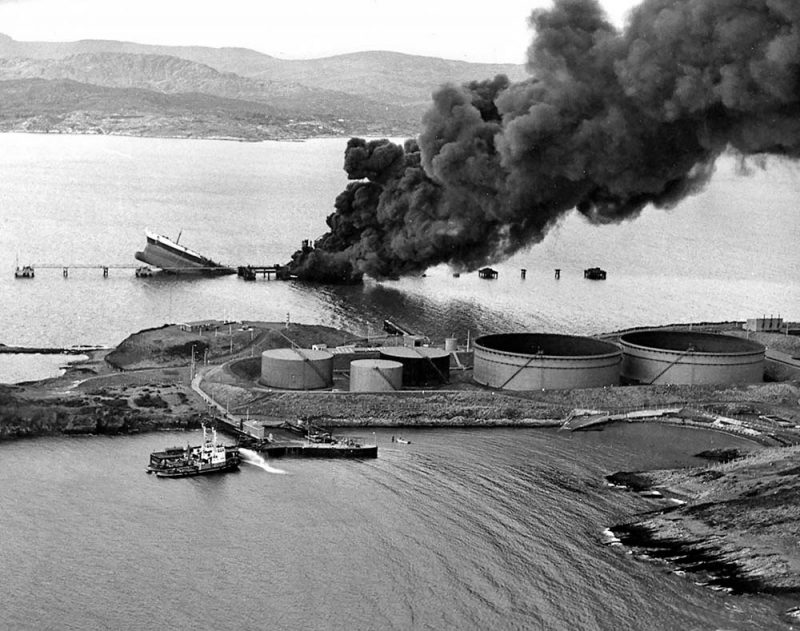

On 29th October 1979, one of the ten holds of the twin funnelled ore/oil combination carrier Berge Vanga of 227,900 dwt owned by Bergesen of Norway blew up. She was five years old and had a crew of thirty onboard, and had sailed from Sepetiba Terminal (Brazil) five days earlier with iron ore bound for Oita in Japan. Wreckage was later reported in the middle of the South Atlantic in position 34°15′ S, 15°20′ W but all of her crew were lost. The Romanian owned tanker Independenta of 150,000 dwt, the biggest tanker owned by Navrom of Romania, exploded in a massive blast on 15th November 1979 following a collision in Istanbul Roads south of Haydarpasa when inward bound from Libya with 95,000 tons of crude oil from Constantza. The cargo ship Evrialy of 5,298 grt was her assailant and loss of life on the tanker was heavy at 54 members of her 56 strong crew. Pollution to the narrow Horn area was huge with considerable damage and anguish caused to property and residents on shore. Black acrid smoke hung over Istanbul for days, and the insurance compensation fund had to remain open for thirteen years to handle all of the claims.

Fire broke out in the accommodation block on the C. Y. Tung owned VLCC Energy Determination of 321,000 dwt on 15th December 1979 when she was entering the Strait of Hormuz from Bonaire bound for the Persian Gulf. An explosion occurred the following day leading to an engine room fire and the ship then broke in two ‘midships two days later. The afterpart sank and the forepart forward of number four tank remained afloat and was declared a constructive total loss.

Seven months later, the C.Y. Tung owned VLCC Energy Concentration of 215,615 dwt, also became a total loss when her mid section ‘jacknifed’ at Europoort with more than 100,000 tonnes of crude oil on board. She presented a very strange and unreal sight but luckily she did not catch fire.

The next disaster was even more shocking as it killed the owner of Maroil S.A. of Madrid as well as his wife and daughter. The two year old Spanish VLCC Maria Alejandra of 239,010 dwt exploded and sank in forty seconds off the coast of Africa at Nouadhibou, Western Sahara on 11th March 1980 while on a ballast voyage from Algeciras to the Persian Gulf. Crew losses were thirty three men, but the loss of the owner and his family meant the end of this tanker operator.

All of these 35 cases of fire and explosion occurred at a time of commercial pressure with very low freight rates hardly paying the cost of operation. Many of the losses could be put down to charter owners not having installed inert gas systems in their VLCCs, and insurance rates were immediately raised for tankers not having these vital cargo systems.

A New Oil Major

There are only four oil majors left from the ‘Seven Sisters’ of the 1950s in Exxon, Chevron, BP and Shell. Chevron (formerly Standard Oil of California) swallowed Gulf Oil of Texas in 1984 and then Texaco in October, 2000 for $45.4 billion in stock and assumed debt. The merged entity had more efficient chartering of tankers instead of separate chartering, including charter of small tankers by Caltex in Singapore, a relic of the huge Texaco empire. Chevron currently has an owned fleet of 26 tankers, including eight VLCCs of 310,000 dwt completed between 1999 and 2010 by the Daewoo and Samsung yards at Keoje Island in South Korea. They have double hulls and are powered by big 8-cylinder Mitsubishi diesels of 40,000 bhp to give service speeds of 14 knots. There is also the long term chartered VLCC from John Angelicoussis in Antonis I. Angelicoussis, as well as ten Suezmaxes, four Aframaxes, two gas tankers and two FPSOs in FPSO Frade off Brazil and Tantawan FPSO off Thailand. All of these owned tankers have names with suffixes ‘Voyager’ e.g. California Voyager except for the gas tankers and FPSOs for reasons of anonymity. Mobil was taken over by Exxon to form ExxonMobil in 1999, although Mobil lubricants had been placed into a joint venture 70% owned by BP in 1996.

The 239,0010dwt Maria Alejandra was built in 1977 by Ast Espanoles at Cadiz. On 11th March 1980 she exploded and sank in 40 seconds with the loss of 36 lives including the company’s owner and his family.

However, a new oil major, Conoco Phillips, has arisen from the merger in August, 2002 of the Continental Oil Company (Conoco) with Phillips Petroleum Company. Isaac E. Blake founded Conoco in 1875 to refine kerosene for the townspeople of Ogden (Utah), his company becoming an affiliate of Standard Oil in 1884. Conoco distributed coal, oil, kerosene, grease and candles in the West, and survived after the dissolution of Standard Oil in 1911 as an independent oil company with its ‘Conoco’ brand gasoline first being sold in 1919. The use of railroad tank cars to transport oil increased its success. It later trailblazed the first petrol filling station in the West after constructing their own refinery as well as developing and patenting the Vibrosis method of seismic oil exploration. After World War II under the leadership of Leonard F. McCollom, Conoco grew from a regional company to a global corporation. Offshore exploration for crude oil sources was conducted in the late 1940s and 1950s, but it was Libyan crude that led the company to acquiring a tanker fleet in 1962. Five mostly Greek owned tankers were acquired and renamed Continental 1 to Continental V, changing their names to ‘Conoco’ prefixes in 1967 e.g. Conoco Jet to transport the Libyan crude to European markets.

Conoco Britannia and Conoco Espana of 116,840 dwt were completed by Spanish yards in 1971, and two VLCCs from Japanese yards in 1973 as Conoco America and Conoco Canada followed by another pair of VLCCs in 1976 as Conoco Europe and Conoco Independence. An oil/bulk carrier had been purchased in 1972 from Norwegian owners as Rinda and renamed Conoco Italia. In 1978, two older tankers were purchased from French and Norwegian owners and renamed Venture Louisiana and Venture Oklahoma, with the rest of the Continental Oil fleet of ten tankers being renamed with ‘Venture’ prefixes by the end of that year for reasons of anonymity. Two of the four VLCCs were scrapped in 1984, with Conoco Independence mostly trading to the LOOP terminal in the Gulf of Mexico while Conoco Europe was in use as a storage vessel at Cayos Arcas, and the rest of the fleet was sold off. The ‘Venture’ prefix was dropped on the two remaining VLCCs in 1988, and they were joined in 1992 by the double hull Patriot, Pioneer, Continental and Guardian of 96,920 dwt. These were some of the first American built double hull tankers as a direct response to the tough OPA90 pollution regulations. The double hull shuttle tanker Heidrun of 124,500 dwt was completed during 1995 in Japan for Conoco Norway to operate from the Heidrun field, 60 miles south of the Arctic Circle, and was renamed Randgrid in 1996. In Millennium year, Conoco made major oil discoveries in Vietnam, the Gulf of Mexico and the North Sea, and purchased the Calgary based Gulf Canada shale oil fields for $4.33 billion to increase its worldwide resources by 40%.

The Phillips Petroleum Company was founded in 1917 by the brothers Frank and L. E. Phillips in the Oklahoma oilfields, having drilled the first of 81 successive oil wells without a dry hole in 1905. The brothers had left their native Iowa after hearing of vast deposits of oil in Oklahoma. The company took over their original oil venture of Anchor Oil & Gas Company, and went on to pioneer propane for home heating and cooking in America, as well as invent a process to make high octane gasoline. Phillips was pumping by 1927 over 55,000 barrels of oil per day from over two thousand wells in Oklahoma and Texas. Phillips first struck oil in Venezuela in May 1946 with chartered tankers to export the crude to American refineries. Production peaked at 30,000 barrels per day but all independent oil companies were forced to leave the country in 1975 when the oil industry was nationalized. Frank Phillips died in 1950 and was succeeded by K.S. ‘Boots’ Adams, who made Phillips into the largest producer of natural gas in America. The trademark ‘Phillips 66’ petrol stations were expanded into Texas and Louisiana and subsequently to all of the American States by 1967. By 1969, oil was also extracted from Nigerian, North African, New Guinea, Australian, North Sea and Iranian fields, and in conjunction with Marathon Oil it spent $200 million on a liquefied natural gas project (LNG) in the same year to export natural gas from Alaska’s North Cook Inlet to Japan. Phillips had the majority control of the project at 70% with the gas transported in chartered Swedish built tankers from the terminal at Kenai, 140 million cubic feet of gas being exported every day for the next twenty years.

A tanker had been purchased by Phillips in 1960 to service its Avon oil refinery at Martinez (California), Hoegh Ranger being acquired from Leif Hoegh of Norway and renamed Avon Ranger. She had been built by the J. L. Thompson yard in Sunderland and was fitted with a four cylinder Doxford oil engine. The tanker was registered under Philtankers Ltd. and managed by London & Overseas Freighters Ltd. (LOF). In 1966, the Getty owned Tidewater Oil Company was purchased, which included five tankers of 84,000 dwt, renamed Phillips Kansas, Phillips Louisiana, Phillips Oklahoma, Phillips Oregon and Phillips Texas, as well as two tankers of 16,450 dwt with ‘Flying A’ names as Tidewater gasoline was sold across America as the ‘Flying A’ brand. The former P. & O. tanker Lincoln of 18,615 dwt and the first to be built for the P. & O. Group was purchased in 1971 and renamed Phillips New Jersey.

The Phillips North Sea exploration programme was enormously successful in 1969 with the discovery of the huge Ekofisk field. A pipeline was constructed to their Teesside refinery, jointly owned with ICI, and was in operation by 1975 and is still a major contributor to British oil exports. Two of a class of four shuttle tankers of 54,000 dwt built in 1979/80 were also used in the North Sea, and Phillips Oklahoma of this class was in collision off the mouth of the Humber on 17th August 1989 with another tanker, causing considerable pollution. Phillips Arkansas, Phillips Venezuela and Phillips Mexico were the other shuttle tankers, and were renamed Hawk, Eagle, Condor and Falcon in 1996 for reasons of anonymity. The VLCC Phillips Enterprise of 1973 became a storage vessel at the Espoir terminal between 1982 and 1989 and was then sold, while another VLCC was purchased as Kollbjorg in 1979 and renamed Phillips America and traded until 1984.

Phillips Petroleum owned one tanker of 152,405 dwt in 1995 to service its offshore Chinese field discovered the year before, and two years later began producing offshore oil from the Timor Sea midway between Australia and Timor. Further oil discoveries were made in Bohai Bay off the Chinese coast in 1998, and buoyed by these discoveries it merged with Conoco on 30th August, 2002 to form the third largest oil and energy company in the United States. The remainder of the Canadian operations of Gulf Oil had also been purchased, and in April, 2000 under Managing Director James J. Mulva it had increased its exploration and production operations by acquiring the Alaskan assets of Atlantic Richfield (ARCO). The deal allowed BP to complete its $28 billion acquisition of ARCO, which had been formed in January, 1966 when Atlantic Refining Company (formed 1874) merged with the Richfield Oil Corporation. A further merger took place in 1969 with Sinclair Oil, thus combining three long established American oil companies that had owned tankers since 1916. Atlantic Refining contributed ten tankers to ARCO including the new Atlantic Prestige of 34,500 dwt and Atlantic Heritage of 53,200 dwt, both built in 1963. Sinclair contributed a dozen tankers including Sinclair Texas of 50,000 dwt built in 1963 and Sinclair Colombia of 58,500 dwt completed in 1965, and Richfield Oil contributed one tanker. ARCO operated ten tankers in 1996, eight of them carrying crude oil from Valdez to the company’s refineries in Washington and California, all with ‘Arco’ prefixes to their names.

Conoco and Phillips agreed a $15.12 billion merger in August, 2002, thus becoming the sixth biggest oil company in the world and an oil major. It had 8.7 million barrels of proven oil resources, 1.7 million barrels of daily production, and 2.6 million barrels of refining capacity. During its first year of trading, the new oil major reported profits of $4.74 billion on turnover of $105 billion, with 75% of its total spending budget allocated to exploration and production. Polar Tankers Inc. was formed to operate five twin screw tankers of 141,700 dwt for Alaskan trading with ‘Polar’ prefixes to their names e.g. Polar Adventure and completed during 2004/06 by Avondale Shipyards at Avondale (Louisiana). They are double hull tankers and powered by 7-cylinder B & W diesels of 30,000 bhp to give service speeds of 16.5 knots. The current ConocoPhillips fleet contains two of these Alaskan tankers and the shuttle tanker Randgrid operating in the Norwegian Sea, as well as the survey vessel Spurn Haven II working in the North Sea. ConocoPhillips focusses its American petrol retailing on its ‘Phillips 66’ and ‘Conoco’ brands in America using both the Phillips 66 ‘shield’ signs and the red ‘lozene’ Conoco signs on the highways and petrol stations, as well as selling its ‘Jet’ brand of petrol in Britain.

Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) Carriers

Liquid natural gas is now considered to be the biggest growth area in the world petroleum markets. This fossil fuel is abundantly available, environmentally friendly, and with enough reserves to last 250 years. Gas reserves in the past have been left in the ground or flared off, but now are liquefied at cryogenic temperatures of -167 degrees C and transported to countries across the world. There were 145 LNG carriers operating worldwide in 2002 and over 200 in service in 2007, and 360 in service at the beginning of 2012. LNG re-gasification capacity in 2002 was 155 billion cubic feet or 2.8 million barrels of oil equivalent, and which had doubled by 2010. Exxon, the largest oil major, has 30% interests in the Ras Laffan Gas Company gas streams in Qatar in the Persian Gulf, which are transported in long term (25 years) chartered LNG carriers. Ras Laffan will be the main shipment port for the bulk of available world LNG supplies with four separate Ras Gas LNG Trains, which allocate huge blocks of gas to long term partners.

The first LNG carrier departed from Ras Laffan port in December, 1996, and the port now has six LNG berths for loading gas for various destinations around the world. Qatar holds the third largest natural gas reserves after Russia and Iran with an LNG export capacity of 77 million tones per year. Charterer RasGas currently has a dedicated fleet of sixteen large LNG carriers, with Maersk Line having so far allocated seven giant LNG carriers of 163,500 m3 capacity on charter to the Qatar gas trade in Maersk Ras Laffan, Maersk Arwa, Maersk Magellan, Maersk Marib, Maersk Meridian, Maersk Methane, and Maersk Qatar. Maersk leads a gas carrier pool of three shipping companies that is ranked the second largest in the world after the Shell LNG fleet. The cost of each of these vessels is prohibitive at between $165 million and $220 million. Qatar Shipping Company, a wholly owned subsidiary of Milaha (Qatar Navigation) recently purchased another 20% ownership in Maersk Ras Laffan and Maersk Qatar from Maersk to take their ownership to 40% and these two ships were renamed Milaha Ras Laffan and Milaha Qatar in early July 2012. A commemorative plaque was presented to the Master of each vessel by their new owners and managers in a ceremony at Ras Laffan Port.

The Maersk Oil Division has been the main profit maker of the Maersk Group in recent years, followed by its Ports Division (APM Terminals), and then a long way behind its Container Ship Division. Maersk will in future switch away from its container ship and terminals business, and concentrate instead on its Oil Division with more LNG carriers and drilling rigs. Seven drilling rigs are on order at a total cost of $4.5 billion, and the Maersk target for oil production for the year 2020 is 400,000 barrels of oil per day with an annual investment in tankers and rigs of between $3 billion and $5 billion.

Teekay LNG Partners was awarded seven LNG charter contracts in 2005 by Ras Gas II (Qatar), and these were fulfilled by seven new LNG carriers named Al Areesh, Al Daayen, Al Huwaila, Al Kharsaah, Al Khuwair, Al Marrouna and Al Shamal completed in 2007/08 with either steam turbine or diesel main engines. Teekay also has two LNG carriers on charter to Tangguh LNG in Indonesia in Tangguh Hiri and Tangguh Sago completed in 2008/09, and four LNG carriers on charter to the big Spanish domestic and industrial gas consumer markets in Catalunya Spirit, Galicia Spirit, Hispania Spirit and Madrid Spirit, and completed in 2003/04. The smaller Arctic Spirit of 89,100 cubic metres capacity was completed by IHI in 1993 at Chita as Arctic Sun and was purchased by Teekay and renamed in 2007. Maran Gas Maritime Inc of Greece headed by John Angelicoussis also has large LNG carriers of 145,700 cubic metre capacity on charter to Qatar Petroleum and Exxon. Another large LNG pool of 22 carriers is the joint venture between CMB (Exmar) of Belgium and Golar LNG, the latter company being indirectly controlled by John Fredriksen. The latest Exmar LNG carrier is Exemplar of 151,000 cubic metre capacity and completed in 2010 with four big membrane gas tanks and eight cargo pumps.

Shell is a leader in the LNG carrier field, having managed these type of vessels since 1964 and has owned them since 1972. Shell had 12 LNG tankers in service in 1996, kept busy with the export of LNG from Brunei to Japan and from Nigeria to the United States. They had 27 LNG carriers in service in 2008 with another 20 such vessels managed a year later for the Qatargas IV LNG project. Their Floating Gas, Production, Storage and Offloading (FGPSO) vessel Prelude is under construction in South Korea and will be positioned off the West Coast of Australia as the largest vessel of its kind in the world. It is almost half a kilometre long at 488 metres, with a deck length of over four football pitches and fifty million litres of water will be drawn from the ocean per hour to cool the gas during production. Their previous biggest offshore oil field was the Bonga field, 120 kilometres southwest of the Niger delta, and had been licensed in 1993 with the first oil produced in November 2005 from the Tyne built FPSO Bonga. Bonga has a capacity for two million barrels of crude oil as well as 150 million cubic feet of gas per day, with the project operated by Shell and the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation, with also Exxon, Agip and Elf as minor partners.

BP has also had a great deal of experience with LNG carriers, managing five such vessels for other owners from 1993 under contractual agreements with the Abu Dhabi project and offshore North West coast of Australia project. This oil major has a twenty year agreement with Sonatrach of Algeria to import LNG into the Isle of Grain since 2005, this amount being 5% of British gas consumption. Three owned LNG carriers of 138,000 cubic metre capacity joined the fleet in 2002/03 for general trading rather than specific LNG project contractual requirements. British Trader joined the fleet in November, 2002 and sisters British Innovator and British Merchant were delivered during the first and third quarters of 2003. They are currently used to transport 750,000 tonnes of LNG per year from Qatar to Spain, and from new, expanding fields in Indonesia, Algeria, Malaysia and Trinidad to the United States. Four more LNG carriers of 155,000 cubic metre capacity were delivered by the Hyundai yard in South Korea in 2007/08 as British Ruby, British Emerald British Sapphire and British Diamond. This ‘Gem’ class trades with Atlantic LNG from Trinidad to New Jersey, and after arrival their main engines are shut down in port with their systems provided with electricity from shore via ‘cold ironing’ techniques.

The oil major Chevron announced a further major discovery of natural gas on 25th October 2012 some 75 miles north west of Barrow Island off the Western Australian coast. The well was drilled at a total depth of 15,023 feet in 3,570 feet of water near to previous discoveries of natural gas by Chevron, which is the operator of this concession with a 50% share alongside Shell and Mobil Australia Resources Pty Ltd. each holding 25% shares.

Their LNG carrier Northwest Swan is one of eight sister ships of 125,000 cubic metre capacity, all with ‘Northwest’ prefixes to their names, that transport the natural gas to Japanese and Korean industrial and domestic users from Withnell Bay, Western Australia. The first of these eight LNG carrier sisters came into service in 1989 as the North West Shelf of Australia LNG fleet for a consortium of most of the oil majors and Australian oil companies.

Conclusion

The oil and gas industry is currently being transformed by the exploitation of huge deposits of oil shale, particularly on the Canadian and United States border. The United States will once again become a major exporter of oil, but oil it is not an infinite resource and will run out at some point in time around 50 years from now. It is thus natural for the oil majors to try and protect their futures by investing most of their spending budget in finding the remaining oilfields of the world. These tend to be in the most remote and challenging parts of the world e.g. the Arctic Ocean and require huge amounts of capital to be expended in the drilling of hopefully productive wells. Thus, the transportation budget is of much lesser importance as the oil major may not wish to invest the capital in building expensive new double hulled tankers. Thus, the chartered oil tanker and LNG carrier will play a much greater role in future than in the past in transporting crude oil, gas and products across the seven seas of the world.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item