Still Guarding Cornwall’s Notorious Reef.

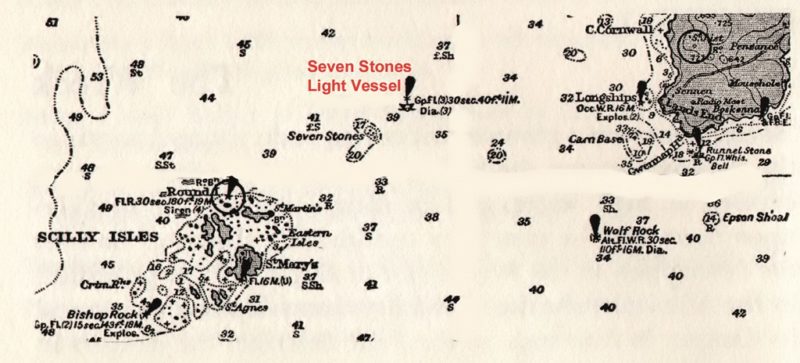

The rock lighthouses of the south-west coast are particularly well known: Bishop Rock, Wolf Rock and Longships, but one less famous seamark, the Seven Stones light vessel has for more than 180 years attempted to warn mariners away from the treacherous reef after which it is named. Situated almost half way between the Isles of Scilly and the Cornish mainland the Seven Stones have, together with the surrounding area, contributed to its earlier reputation as a graveyard for shipping, a continual reminder of which is the collection of figure heads from wrecks displayed in the Valhalla Museum at Tresco Abbey Gardens. Weather-wise, the region experiences the strongest Atlantic gales unopposed and while the lighthouse keepers faced the storms in reasonable comfort, the crew of the solitary lightship had to endure its continual and often violent movement, occasionally suffering damage to themselves and their vessel.

Since 1841 a succession of vessels has maintained, at first two fixed lights, then a flashing light to warn away mariner. Revolving optics consisting of oil lamps with concave mirrors were used for a long time for it was not until 1954 that an electrified ship was moored on the station. Today an array of solar panels provides power for the lamp and fog signal of the automated lightship, one of the few remaining in British waters.

It is clear that the building of the lighthouses and the mooring of the light vessel (LV) only reduced the number of wrecks but frequently the latter, perhaps ignored or unseen initially, ultimately offered a refuge for those who abandoned their ships as they sank beneath them. This two-fold purpose of maintaining the light under all conditions and being in close proximity to the reef was to place at times extra and perhaps sometimes unacceptable demands on the crew, especially as the vessel was moored in 40 fathoms of water, far deeper than any other Trinity House vessel.

Mooring the First Floating Light Proved Difficult

At the start of the 19th century lighthouses existed only on St. Agnes in the Scilly Isles and the Longships off Land’s End. Various parties including the Chamber of Commerce of Waterford and a number of Bristol and Liverpool traders felt this was not enough and made requests to Trinity House, leading to a meeting in 1836 when an agreement was reached that the latter would survey the area. As the Corporation now favoured lightships in contrast to their total opposition to the Nore a century earlier, they agreed to proceed and a vessel was towed out from London in August 1841.

Severe problems were soon encountered in maintaining position at the site chosen to moor the lightship. It continually dragged its anchor, almost stranding on the reef on one occasion.

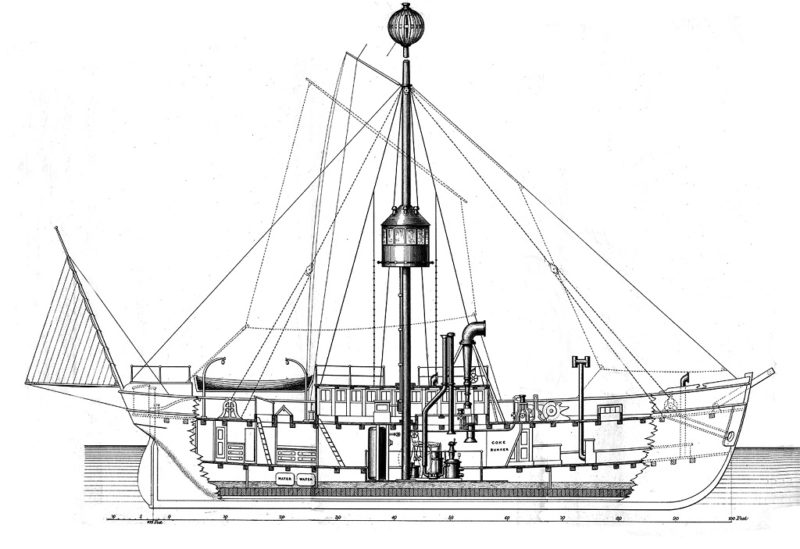

Hence the length of the chain riding cable carried was increased from 200 to 300 fathoms, which required more crew to handle it, but all through 1842 the ship continued to drift. Storms added to the problem and it was not until 18th April 1843 that the Seven Stones lightship was securely moored. Eleven crew members were needed instead of the normal seven, mainly to work the manual windlass, as more cable had to be let out as the sea grew rougher and hauled in as the weather moderated.

Lightships always rode on the pile of cable on the bottom which, besides giving a smoother motion, meant that the least strain was put on the mushroom anchor. Her eventual position was Latitude 50°3’40”N, Longitude 6°4’30”W

Misfortune was never Far Away

Although some light vessel masters claimed that the Seven Stones ships rode more easily on the long Atlantic rollers than the short broken seas of the English Channel, the evidence over the long term indicates a hard life punctuated by gales that threatened injury to the crew and damage to the ship. A carpenter was always carried in Victorian times who could repair modest damage from the stock of timber kept aboard. Records suggest that the level of injury and frequency of accident was higher here than other stations, while the log included shows there were deaths from illness, falling and being washed overboard in addition to drowning from the capsize of the longboat. Some older crew members also retired due to ill-health after service at the Seven Stones.

Once established the vessel was serviced from St. Mary’s with the crew housed on Tresco in houses provided by Augustus Smith, the owner of the Scilly Isles. This proved the most convenient arrangement as the ship could be observed from the latter. It was not without danger though, because on 15th October 1851 the longboat capsized returning from St. Mary’s with the loss of two of the crew.

A different problem arose in 1866 when Augustus Smith received a letter from Trinity House complaining that the dwellings on Tresco were not being properly maintained and demanded that he put things right as this deficiency might affect the general performance of the crew housed there. Mr. Smith, being a straightforward individual came back saying the problems of upkeep were directly related to some of the occupants. Captain Arrow of Trinity House still demanded that he make everything satisfactory and also grant them a further lease for 22 years, neither of which Augustus Smith agreed to do. The correspondence having become acrimonious, Trinity House had little option but to move the crew and tender to Penzance, a far less convenient base as signals could no longer be exchanged with the lightship.

There followed a series of wrecks on the Seven Stones which brought survivors in their boats to the lightship but which also caused complaints and criticism about the management of the vessel – Was its light good enough? Was it there to act in a life-saving capacity? When installed the vessel showed two fixed lights, one higher than the other, on two masts. When the S.S.Oxus mistook the vessel for the Longships lighthouse in August 1869 and ran onto the reef, the subsequent Court of Enquiry allowed her master’s claim that the Seven Stones light had not been properly displayed. However, it was to be ten years before a much better light was exhibited.

Falling Stars

A strange occurrence befitting of this wild location occurred on 13th November 1872 in the shape of a meteorite. After the shock of the impact stunned those on watch, balls of fire, like large stars were seen falling into the water in a remarkable firework display. A strong smell of sulphur followed while the crew crushed cinders underfoot as they trod the deck, but all had been washed overboard by rain and sea before daylight, making it difficult to believe what had happened.

Improved Vessels Reach the Seven Stones

Experiments with improved fog signals had resulted in the installation of Holmes’ patent foghorn powered by an Ericsson caloric engine at the Seven Stones in 1871, probably aboard LV45. Eight years later in September 1879 LV50 arrived, a new, specially constructed vessel equipped with Brown’s caloric engines to compress air to power the siren fog signal and drive a Harfield windlass. This vessel also had an early version of the new 8-foot diameter lantern with 21 inch mirrors capable of generating up to 4,000 candle power, which with three to a ‘face’ meant each flash radiated 12,000 cp. Interestingly LV50 was also fitted with a whaleback over the poop to avoid seas flooding the afterdeck. Trinity House regulations stated that lifelines should always be rigged in bad weather.

Wreck and Rescue – Not Always!

Storms pounded the vessel in October 1886, causing severe damage, requiring its withdrawal for repairs. There then followed a series of wrecks, the first causing controversy. On 2nd July 1887, the full-rigged ship Barreman sailed from Shields for San Francisco. A day or so later the remains of a sailing ship were sighted on the Seven Stones, the weather being foggy with a heavy ground swell. There was no sign of the crew of 27. The subsequent Court of Enquiry, held at Glasgow, examined the course taken by the Barreman, a name board of which had been found, and also inquired into the inaction of the light vessel crew in not making any attempt to save the lost men.

The Court went further, unusually, in preferring charges of Culpable Negligence and Inhumanity against the Mate of the Seven Stones. This finding was surprising because lightship crews were never expected to leave their vessel and were actively discouraged by Trinity House from doing so, for if they could not return to their ship for some reason, they would not be able to maintain a light, which was the ultimate purpose of the service. This point was made at the enquiry, as also was the comment that there were only seven crewmen aboard, the extra four provided earlier having presumably been removed when the mechanised LV50 arrived. There was a good deal of public rancour at the time encouraged by the press reports which did not help.

Wrecks continued throughout the 1890s. Survivors from the steamships Chiswick and Camiola arriving alongside in their own boats to be picked up later by the Trinity tender. The millennium year 1900 was memorable for a severe storm on 29th December. So severe was the weather that a large section of the bulwarks of the ship was carried away, and a boat smashed against one of the ventilators in the process of which it trapped one of the crew and tore away a piece of his thigh. Another man’s face was lacerated from his eyebrow to his chin. Two shipwrights on this occasion required three weeks to repair the damage but LV54 was brought in early for refitting as a consequence.

Calmer Times and Better Ships

The Edwardian period was relatively calm, except for the sad death of John Richards who fell from the deckhouse roof on to the main deck on 11th June 1909 fracturing his skull. For once weather was not a contributing factor. With the advent of wireless communication wrecks became fewer, and having survived the War the wooden LV56 was replaced by iron vessel LV72 in the peacetime that followed. Both ships were fitted with Hornsby Ackroyd 14HP hot bulb oil engines to drive air compressors to power the windlass and fog siren, a considerable improvement on the coke fired caloric engines, as they burned paraffin and could be started relatively quickly.

LV72 was replaced eventually by LV80 on 20th November 1939. Although relatively modern the latter still had Argand oil lamps with concave mirrors for its light but it had more powerful 22HP Hornsby engines better able to handle the longer lengths of mooring cable, the only Trinity House vessel so fitted. Its time on station was short, however, for enemy air attacks caused its withdrawal in May 1941, a gas buoy being moored in its place.

LV80 Breaks Adrift and Breaks Down

LV80 was returned to the Seven Stones in January 1947, a very bad winter with storms also returning later in the year to take the life of lightsman Albert Hill, washed overboard from the light vessel at the beginning of November while attempting to bring the ship’s boat inboard.

In March 1948 it was the ship’s turn to suffer, breaking adrift and driving up the coast as far as Pendeen lighthouse before it could be anchored. William Harvey from Newlyn was aboard on that occasion, one he was to remember later when as Master of LV13 at East Goodwin he was to drift within a whisker of the Sands in an easterly gale before catching his hook on a cross-channel telephone cable. He was accorded celebrity status by the media for saving his ship and awarded the BEM. LV80 was re-moored on 16th April.

Two-and-a-half years later in November 1950 an incident occurred which would change the lives of the crew completely. While in operation the massive flywheel of the starboard 22HP Hornsby engine broke free, causing considerable damage to the ship but fortunately no injuries to the crew. Again the vessel had to be withdrawn but a further problem arose.

The replacement immediately available was the almost new electric ship LV3, (the light vessel numbering system started again after the Second World War). Unfortunately the Seven Stones crew were only trained on oil-lit ships with ancient Hornsby engines so could not operate it, thus an alternative had to be found in the shape of the equivalent LV66 which at that time was at the Owers and had to be withdrawn to serve at the Seven Stones. Repairs were rapidly carried out and LV80 was soon placed back on station. At this point Trinity House must have decided to fully refit the ship, converting it to electric light and providing Gardner engines and Reavell compressors in the process.

Thereafter the human cost of service at the station became more apparent. Edward Sowden boarded the ship at the very wet Christmas changeover of 1952 only to be found dead in his bunk the following 23rd February. A doctor and detectives visited the ship but his death appeared to have been due to natural causes.

New Lamps for Old – Modern Comforts Arrive

In July 1953 LV80 was withdrawn for refitting and eventually returned in March 1954, completely modernised, electrified with hot-water showers, refrigerator and improved accommodation. It was to remain there until October 1958 when it was replaced by the brand new LV19 which was one of the most advanced vessels built for Trinity House, its 600,000 candela light being somewhat greater than the 2,000 output from the vessel of a century earlier.

The Torrey Canyon Wreck puts the Seven Stones on the MaP

Sick crewmen were taken off by lifeboat in May 1960 and June 1963 but the event that really put the lightvessel and the Isles of Scilly on the map was the wreck of the supertanker Torrey Canyon, one of the largest in the world, on 18th March, 1967.

Despite firing four rockets and signalling by Aldis lamp in warning, the tanker drove straight on to the reef, eventually releasing most of its 100,000 tons of crude oil to pollute the Cornish and some French beaches on a massive scale. In order to try to reduce the amount of oil escaping a decision was made to bomb the wreck to set it on fire, a move which was largely successful but required the lightship to be towed into Penzance while it took place.

On 30th August 1972, Wilfred Johnson aged 62, Master of the Seven Stones, collapsed onboard and was brought ashore by helicopter, sadly dying the next day. Six years later the crew reliefs were carried out in the same way, which at last avoided the hazardous transfers of men in heavy weather, however in similar conditions the helicopters were still unable to land and delayed reliefs still occurred.

Before that the boats would always try, as in November 1969 when First Sea Lord Sir Michael le Fanu made a courtesy visit in conditions which were at the limit for launching a boat. He wished to learn more about the operations of Trinity House and afterwards complimented all concerned on the standard of their seamanship.

Automation Arrives – The Crew comes Ashore!

Automation, which commenced with Calshot Spit, and progressed through the east coast vessels, finally arrived at the Seven Stones in October 1987 after the crews had arrived and left by helicopter for the previous ten years. ALV24 was left unmanned with a continu- ously running diesel generator to power the light and fog signal. When the Admiralty allowed for the power of the lamp to be reduced late in 2007, a solarised vessel replaced the diesel one, and so it remains today.

Today the Sevenstones lightship acts as a weather beacon as well as a seamark (The station name has been painted as a single word since the arrival of LV19 in 1958). As part of the NOAA coverage of the world’s oceans it acts as buoy No. 62107 of the National Data Buoy Center in conjunction with the Meteorological Office, continuously transmitting data on wave height, sea and air temperature, barometric pressure etc. As an aid to navigation it has a Racon which shows a ‘paint’ of the Morse letter ‘O’ (- – -) on an approaching ship’s radar screens and it responds to AIS interrogation (MMSI No.992351023). The operation of the vessel is monitored by Trinity House staff at Harwich.

Reflections

Graham Fearn, Principal Keeper at Bishop Rock lighthouse called “A Cheery Good Morning” by radio to the Master of the Seven Stones vessel one stormy day, continuing, “Is it a bit slippery underfoot your way this morning, skipper?” Back came the reply, “I should say so, the seas are coming down here the size of council houses!”

Trinity House in the video ‘Stormswept’, demonstrated the landing of a seriously ill seaman from the same vessel in similar conditions in the 1930s by a boat from the tender Satellite. The choice of Seven Stones for that film was very apt in consideration of the rigours of that station which Michael Tarrant also recalled vividly in his book ‘Trinity House, the Super Silent Service,’ including the time when another lightship master’s nightmare occurred in the shape of the riding cable becoming foul of her anchor, the problem increasing with each swing of the ship with the tide.

As the Seven Stones had such a long cable the tangled mass on the seabed was considerable, needing the tender’s heavy lift derrick to raise it to the surface. The recovery had to be carried out on a calm day.

The ship’s current state is very different from the long years of manning and the crew’s trials and tribulations of raging seas and shipwrecks. Their record stands as one of courage, fortitude and endurance in the face at times of extreme adversity.

They were unsung heroes who often had to work with one hand holding on. Their lot may not have been a great deal harder than those who went to sea generally and other lightships suffered numerous collisions, hazards the Seven Stones seemed to be spared, but merchant seamen could often seek port or shelter when storms occurred and the lightships could not!

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item