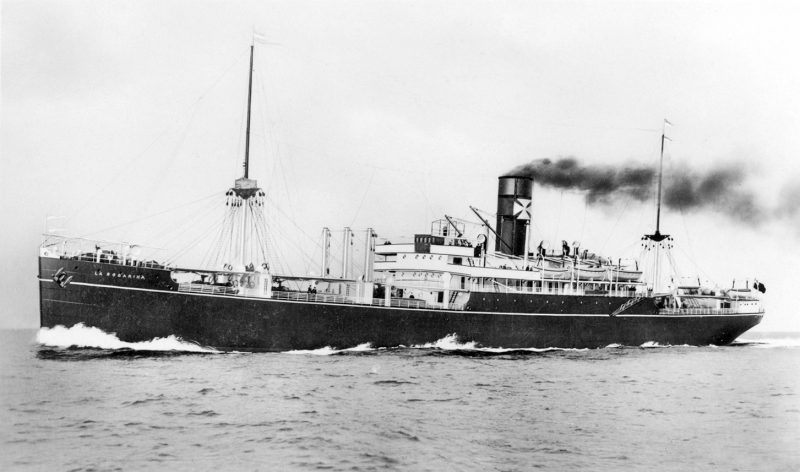

The ‘La Rosarina’

My last ship before the end of the war was one with a very beautiful name. The La Rosarina (The Rosario girl) was a large frozen meat ship belonging to Houlder Brothers and permanently on the Liverpool to the River Plate run. I have since lost all my records relating to her statistics but she was about 10,000 tons gross and had been the largest refrigerated ship in the world in her time. For a purely cargo ship, she was quite imposing, although hardly beautiful. But there was a very solid and powerful look about her which inspired confidence. The meat carriers were reckoned to be very safe ships to be on because of their massive compartmentalisation. A cadet shipmate told me that he had been torpedoed on the Condesa some months earlier and she had taken nearly 24 hours to sink. One’s survival in war hangs on such fortuitous circumstances as this. The cadet in question was W. Myerscough who later became Captain Myerscough and had a distinguished career as Navigation instructor at a famous London navigation school.

My senior was Robert Eric Blair, a chap just a year older than myself so we became good pals. As I have already related, he had narrowly escaped with his life from the torpedoing of the Tortuguero and he was more than a little nervous on that account. Before leaving Liverpool he had taken me to visit his family who were living in New Brighton at the time and they were very kind to me indeed. He had a very beautiful sister and after we had all spent a very happy day on the New Brighton beach, Blair and I caught the ferryboat Daffodil back to the Liverpool Pier Head en route via the famous overhead railway to our ship which was sailing at midnight.

A word here about the Liverpool overhead railway. By this time I had become very used to hopping on and off this magnificent train. It ran between Garston in the north and Seaforth in the south skirting the whole line of Liverpool docks en route. I can hardly imagine anything more valuable to a seaport than this well-thought out line.

The La Rosarina turned out to be a comfortable, well-fed, and well-found ship and I enjoyed my one three-month voyage on her very much. However, there were drawbacks, such as the fact that, in keeping with our ‘Aunt Sally’ tradition, we were relegated to the engineers mess room for meals. From a navigating officer’s viewpoint then, that was as low as we could go. It didn’t end there because we were sub-divided again by the Second Engineer (the titular head of the mess) to eat at the refrigerator engineer’s table. At the main table were the six or seven engineers and at the other the three ‘freezer’ engineers and the two radio operators. That kind of thing didn’t bother me much then and I usually got on well with all my shipmates. But they were a stuffy crowd and no mistake. Always on their dignity and obviously suffering from an inferiority complex a mile wide. Everybody deferred to the ‘Second’ in conversation while at our table everybody deferred to the ‘Chief Freezer’. He happened to be much the oldest man there and as such was shown a good deal of respect by all including the mighty ‘Second’.

Blair and I held our end up quite well and I don’t remember any trouble except with one odd character who was reputed to be 4th Engineer but who wore the uniform of a Lieut-Comnander R.N. and who acted as such. We never did find out what he was doing on the ship so there sprung up dark rumours that he was on a special mission for the Admiralty or that he was a secret service man of some kind or other. His name was Davies and I was told that his home was Hooton Hall in Cheshire. We never did find out about him, and Blair had a first class row with him when he demanded that a copy of the news bulletin received each night be sent to his cabin in the morning.

The Chief Officer was Percy Lavender, lst Officer Mr Harrison, 2nd Officer Mr St. Pierre and the 3rd Mr Hoffman. Mr St. Pierre was French but was I think naturalised for he could not have held a Master’s Certificate otherwise. Dark and Gallic looking and very much in love with his girl in Liverpool. I saw him more than once, weeping over her portrait, but he was no sissy for all that and was well liked. Years later I heard that he became Marine Superintendent for the Houlder Line which is a good measure of his efficiency, and during the sixties while working on a Houlder Line new vessel being built in Burntisland I was told by the then superintendent that my old shipmate was dead.

But the bête noir of the La Rosarina was the captain, whom I have no hesitation of placing in my private category of ‘difficult’. Fortunately, as a junior, I did not come into contact with him very much, but poor old Blair had to put up with a good deal of abuse at times. He was small, insignificant looking and decidedly nasty. He never said a kindly word if there was a handier brutal one, and he led his navigating officers a dog’s life.

We were still in the period when a shipmaster had complete power over his crew, and there was never much chance for a seaman to buck that power. To disobey a lawful command by the Master was punishable on the spot by fines and the docking of a days pay. In extreme cases the seaman could be put in irons. Also there was the final sanction of a ‘bad discharge’. If a seaman’s discharge book at the end of the voyage was endorsed ‘DR’ for ability and conduct (decline to report) he would have much difficulty getting another job. Technically anyone could be given a bad discharge, but it was very unusual for an officer to be given one such, although it could happen and I have actually seen it.

In the case of one very well known Shetland master in the employ of a well known Leith shipping company, he was known to have given bad discharges to almost all his crew, including officers. Nowadays such conduct would not do a master any good because his rulings would probably be reversed by the Shipping Master, and in any case, his own employers would not stand for it. I have heard of threats that masters were more easily obtainable than ABs or junior engineers, and it is also a fact that many of the old powers of the master over his crew are now gone forever.

The only criterion that carries much weight now is the age-old situation of ‘the safety of the ship’ on which only the master can rule. Ships Articles in the early part of the century were still much weighted in favour of the shipowner. They had to be read out to the crew when they gathered in the Shipping Office to sign on. The Agreement was for two years on a foreign-going ship which could not be broken by a seaman except at the final port of discharge at the end of a voyage, or at any port between the Elbe and Brest. There were many bye-laws to be observed by the seaman, the principal one being against the bringing on board of ‘spirituous liquors’. Sometimes those signing on sessions were quite hilarious. Many men would be pretty drunk and eager to get back to the pub. One old Welsh Shipping Master in Barry Dock used to read the articles at a great rate but he would slow down very considerably over the ‘spirituous liquor’ paragraph. I can also remember a Chief Engineer demanding a delay in sailing because his second engineer had not turned up only to be told testily by the shipping master that there were only two members of the crew that a ship could not sail without, namely the cook and the Radio Officer.

We had a considerable submarine scare outward bound while still in the Irish Sea and our escort of destroyers went careering around dropping depth charges. One of those landed fairly near and nearly lifted us out of the water. Blair jumped to the conclusion that we had been ‘bumped’ and set about preparing to send a distress signal if he was ordered to do so, while I was given our confidential books to destroy by dumping overboard in their lead covers. It was all very exciting and I went out on deck to see what was going on. Fortunately we had not been torpedoed and I don’t think any of our convoy suffered more than a good fright.

From then on our trip towards the River Plate was uneventful and we arrived at Monte Video late in August, and left almost immediately for Buenos Aires, about l00 miles further up the Plate estuary and on the Argentine side. We arrived there the next day and for the next two weeks were busy discharging a general cargo and loading frozen beef for Britain.

Argentina at that time was very such a British orientated country and a landmark visible for miles out in the river was the huge bulk of Harrod’s department store. All the Argentine Railways were British built and owned, a state of affairs that continued until into the Second World War when they were regrettably sold for the cash or credit that we so badly needed then.

Buenos Aires was a very beautiful city with very many fine wide boulevards and splendid buildings. The main thoroughfare was the Avenida de Mayo which led into the fine square of the Plaza de Mayo. On one side of the Plaza (nearest the dock area) was the magnificent Casa Rosada, the principal residence of the President, so-called because of its rose pink colouring. I am not sure to this day if that colour was natural or had, been painted on. Of course there were many rather sleazy streets and the dock road was skirted by a continuous arched walk way or broad pavement. Here all the delights of a sailor town could be found. Small drinking bistros and bodegas where almost anything, from a needle to an anchor could be purchased. The narrow street called ‘25 do Mayo’ which led off the plaza to the westward was the home of some pretty rough music halls, where French style variety shows proliferated. Those shows were reckoned to be pretty naughty in that day and age, but compared with what goes on in Europe these days, they were quite innocuous.

A good deal of our time was spent at the Victoria Sailor’s Home which was run then by a Mr Parker. In fact, Buenos Aires was well served then by the Missions to Seamen and the local branch of the ‘Flying Angel’ was well patronised by seafarers generally. It is a sad fact that most people started to go there only when their money had run out, but apprentices and impecunious wireless men tended to be the best customers of what was after all very generous free entertainment. The principal ‘Mission’ at that time and for many years after was made famous by the presence of the ‘Fighting Parson’, Canon Brady of the Church of England. This title had been earned years before by a certain Canon Karnie and had passed on honourably to Mr Brady. They were both very skilled boxers and used to perform in the well-equipped ring at the Mission. A boxing night each week was a sure way of bringing in the sinners from the Merchant Navy and some very real talent was in evidence. Brady himself occasionally provided one in which he fought with three hefty cadets at the same time. The results were often very hilarious. Young Argentine boxers used to turn up frequently to practice their skills and earn a few pesos at the same time. Many years later I was to see a very good professional fight there between Pancho Villa and the second cook of the Raphael. Canon Brady was a somewhat controversial figure in the legends of Buenos Aires. In some ways I think he was a bit of a Peter Pan for he used to join in on some of the rough houses we had in cabins on the La Rosarina. Our four apprentices were just like puppies and Blair and I frequently had to fight for our lives when we went visiting the boys. We were all the same age and our scraps were devastating and quite marvellous. I remember the mate, Percy Lavender, looking in one evening when the din must have been appalling. He said “Good God” and beat a hasty retreat. What was more sinister about Mr Brady was the rumour that he was a British Secret Service agent. Whether there was any truth in this I am not sure but it is a fact that some time in the thirties he was ordered out of Argentine at very short notice by the Government.

After loading a large quantity of frozen beef from the various ‘frigorificos’ of Messers Armour and Swift, we left Buenos Aires for our final loading port of La Plato/Ensenada some distance down the Plate estuary. Those ports were very primitive then and held little lure for us so I do not think we bothered to go ashore at all. After the delights of Buenos Aires we had become quite selective! The loading was soon completed and we sailed for home and also for what was to be the happiest of landings about a month later.

A convoy was picked up at Sierra Leone, then a British colony in West Africa, and generally known as part of the ‘white man’s grave’. It was still a fever ridden hole of a place, of which it was said that one either died of malaria or whisky, the idea being that there was no other choice. Fortunately we had not long to wait and the final leg of the homeward voyage was completed without incident when we arrived in Southampton early in November l9l8. This famous port which I was to get to know very well at a later date was a great place for entertainment and Blair and I had a very happy time going to dances, drinking moderately, and also visiting the local music halls. A very happy week’s enjoyment with one of the nicest girlfriends I ever had culminated in the arrival of Armistice Day.

The memory of it has a kind of dreamlike quality. I met my girl some time in the afternoon and we just wandered around the High Street, hand in hand, amidst the milling crowds of near hysterical people. We ate somewhere and then wandered some more, losing all sense of time. The lass lived over the river in Woolston and I suppose it must have been around two o’clock in the morning when we finally found our way there via the ‘floating bridge’. We were saying goodbye when her mother appeared on the scene and tore her from me. I never saw her again. After a brief call at Cardiff, the La Rosarina finally reached Liverpool in late November 1918 where we all paid off and a new era was to start for me.

CONTINUED NEXT MONTH

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item