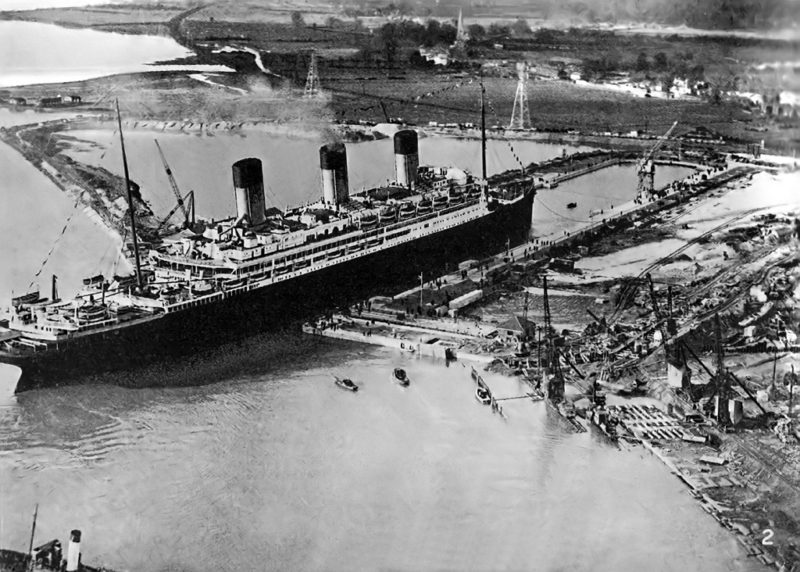

2023 sees the 90th anniversary of the opening of one of the British Empires most ambitious projects but it wasn’t a ship it was the then world’s largest graving dock, the King George V Dock in Southampton. The dock would break world records in capacity capable of accommodating ships up to 100,000 tons in weight and created new construction techniques during its complicated build process. Later the dock would play a vital role in one of the most audacious and daring Commando raids of the Second World War.

Southampton was 90 years ago, like today, at the forefront of the Transatlantic passenger trade and business was steadily growing. The facilities were under strain due to the pressure of work and there was deemed a need for repair facilities suitable for the size of ships that were currently using Southampton as well as the perceived future growth of ships generally. Liners needed repair facilities and Southampton was the perfect location to provide them.

The design chosen for the new dock had been prepared by F.E Wentworth-Sheilds had dimensions of 1,200 feet long, 135 feet wide at the entrance and between buttresses and 59 and a half feet from the dock floor to the ‘cope’ – the engineering term for the brim of the vast dock space. Once inside the entrance the dock would open up becoming 165 feet across and when fully flooded contained 260,000 tons or 58 million gallons of water. Pump houses located around the dock site could empty the water in the space of four hours.

The driving force behind the project to construct the King George V Dock at a cost of £2 million was Southern Railway’s vast project to transform Southampton Docks. Their plans included 7,000ft of deep water quays fronting more than 400 acres of reclaimed land. John Mowlem and Company and Edmund Nuttall Sons and Company secured the contract to build the world’s largest dock. This construction in itself was a magnificent feat of engineering requiring the construction of a long embankment wall. To form a foundation for the quay wall, 146 immense concrete monoliths were sunk into the embankment. At the base of each monolith was fitted a steel cutting shoe so that the monoliths could cut their own way into the embankment. Nine vertical shafts were put into each monolith so that excavating grabs could take away the soil beneath the monoliths to help them sink under their own weight. The new quay wall gave accommodation for eight of the largest liners at any state off the tide. At the western end of the quay wall the graving dock was built.

The site chosen for the graving dock was an uninspiring area of mud flat that had first to be claimed back from the tides of Southampton Water. The engineers first task was to enclose the vast area behind an embankment built of chalk and gravel that had been obtained by dredging the deep water channel into the dock area. The first layer of the riverbed was found to be soft clayey mud, and this was loaded by the dredger buckets into ‘bottom door’ barges and dumped out at sea. Beneath the mud the dredger Bankwell found a good layer of useful gravel which was instead dropped on the emerging embankment.

The Bankwell was a strange looking craft and comprised two pontoons joined together by an overhead framework carrying bucket dredger gear. Between the pontoons there was enough room to accommodate a barge loaded with material. The barge was unloaded by the buckets of the dredger gear and the gravel was deposited on a travelling endless belt which was continued from a long steel boom. The arm projected over the side oof the Bankwell so that at all states of the tide it was possible to drop gravel on to the ever growing embankment. The chalk used, in addition to the gravel, for building the embankment was obtained from the Southern Railway’s quarry at Micheldever (Hampshire).

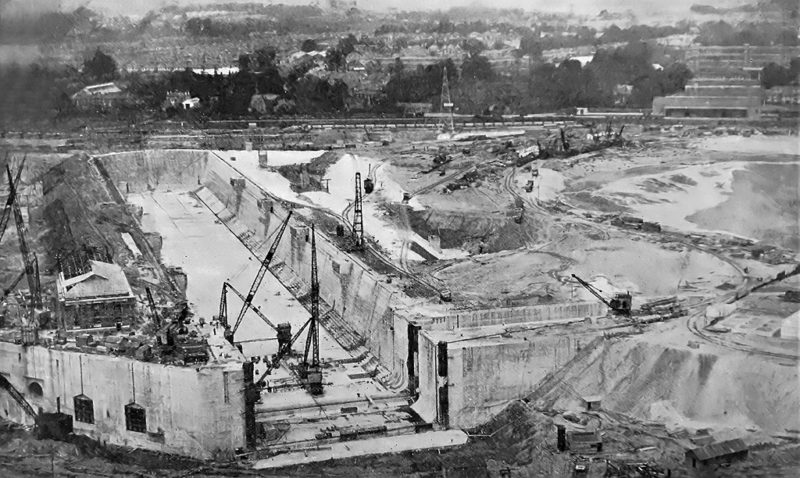

The constant action of the tides in Southampton Water were considered and to avoid the threat of the dredger’s work, the seaward slope of the embankment was covered in a temporary layer of brushwood made up into bundles known as fascines. To prevent the possibility of leaks a continuous sheet of steel plates were driven deep along the centreline of the earthwork with special sluices to allow for the tides ebb and flows. The embankment work was completed in June 1931 and focus shifted towards the task of removing all the water contained within the enclosed area. Numerous float pumps were installed with the work to extract the 50 million gallons of surface water completed in ten days. The engineers still, however, had to find a solution for the deep artesian water deep underground. The engineers decided on a plan that saw the top layer of soft alluvial mud removed by steam navvies and a sump was made at the south end of the dock to drain off seepage water. Once excavation had begun the problem of the underground water had to be tackled. It was discovered that below the dock there existed a bed of sand charged with artesian water at high pressure. Numerous tube wells were sunk into the sank to relieve the water pressure. Inside each were placed pipes, perforated at the lower ends which were themselves covered with copper gauze filters which permitted the passage of water but excluded the sand. Pumps, driven by special electric motors capable of working under water were lowered down the pipes, and the water was thus extracted from the sand. The pressure head of the artesian water was reduced by 90 feet.

Now that the problems associated with water ingress had been tackled it was time to dig out the foundations for the massive graving dock. After mechanical excavators dug out 1,258,000 cubic yards of the mud and other material much of which was recycled, the great walls of the dock was sunk in trenches measuring 43 feet wide and 53 feet deep. The gravel extracted from the site was put through a special process to clean it before it could be used in the building of the dock. The gravel needed to be cleaned in two huge receiving drums before being transferred via an inclined conveyor belt system to storage containers above the concrete mixing facilities. Once mixed in with the concrete the gravel was loaded into bottom door boxes and carried in wagons running along rails to various positions in the dock. The remainder of the spoil was used to raise the level of the ground. The quantity of concrete placed in the walls and floor of the dock amounted to 456,000 cubic yards. As much as 10,000 cubic yards of concrete a week were required at one stage of the work.

The concrete floor of the dock is 25 feet thick. This gigantic slab of concrete, 200 feet wide outside the walls and 1,200 feet long, served the double purpose of carrying the world’s largest liners on its upper surface and of holding down the great pressure of the artesian water below. The relief wells referred to above were not filled in as the walls rose. The pumps were removed, one by one, and the wells were connected by horizontal drains to the dock, discharging at a distance of 40 feet below the quay. In design the dock wall was rounded at the shore end with a pair of opposed flights of stairs. At intervals of 200 feet along the dock sides were vertical buttresses resembling watch-towers and having for their object the prevention of contact of the bilge keels of vessels with the foot of the wall.

A huge steel caisson to seal the dock was constructed on the River Tees. The caisson was essentially a large rectangular box divided into several separate compartments. It measured 138 ft 6 inches long, 58 ft 6 inches deep and 29 ft wide. The caisson had five decks. Above the bottom deck (or keel plating) is a water ballast tank. The deck next above contains auxiliary air chambers that give buoyancy.

Above this deck are another air cham-ber and additional ballast tanks. The top compartment is ‘free flooding;’ it is 15 feet deep and is partly open at either end. The top of the caisson provides a roadway for light traffic across the entrance to the dock. The total weight of the caisson, including the water ballast (except that in the free flooding compartment), is 4,600 tons. The caisson was built to withstand the pressure of water imprisoned inside the dock and the pressure of the tides outside. The caisson was towed from the Tees to Southampton with the voyage taking over a week at a steady two knots.

The gate’s great weight required the construction of a cavity or ‘camber’ to be excavated at the eastern end of the dock entrance. The caisson would be drawn out of the camber across the entrance to close the dock, and the meeting faces are of greenheart, a hard West Indian wood. If required, the caisson could be floated out of the camber, away from the entrance, and placed against a granite stop outside its usual position. It was then possible to repair the caisson or the other inner stops. An electrically-driven winch, operating massive steel chains, was used to draw the caisson along the steel sliding ways leading from the camber across the dock entrance.

One of the most impressive mechanical feats of the construction of King George V Dock was the water pumps that could empty such a vast amount of water in just four hours. Each 54 inch centrifugal pumps with spindles were arranged vertically with double inlet pipes. Each pump was driven by a 1,250 hp electric motor running at over 270 revolutions a minute. In addition to the main dock pumps were three 16inch high speed centrifugal pumps driven by 200hp motors for dealing with rainwater. All these vertical pumps are equipped with the Michell thrust bearing. To provide ships under repair or refit within the dock with seawater for their auxiliary condensers three special electric pumps were provided in the pumping stations, which also provided a degree of firefighting capability with turbine fire pumps.

The main pumping culverts set within the concrete walls of the dock are 10 feet in diameter, and the storm water culverts measure 6 ft 6 inch in diameter. The culverts re fitted with valves arranged in concrete pits covered with watertight decks. There are eleven valves of 10feet, six of 6ft 6 inches and five of 3 ft diameter. The valves comprise wedge shaped doors that rise or fall vertically in guides across the culverts. The main 10-feet valves were operated by 35 hp electric motors. The whole of the complicated system of pumps and valves was controlled by push buttons by one operator at a central control desk.

Ships under refit at King George V dock could be worked on by a variety of cranes with the dock being equipped with a pair of electric travelling cranes on either side. On the west side of the dock the crane had a capacity of 50 tons, with two auxiliary hoists each capable of lifting 10 tons. The 50 tons load of this crane were handled at a radius of 110 feet, which is 8 feet beyond the centre line of the dock. The east side crane can lift a load of 10 tons at a radius of 60 feet. In addition to the cranes a 30 tons warping capstan was provided at the head of the dock and at either side were two electrically-driven capstans of 10 tons capacity.

When the labours of 1,000 men for the 21 months drew to a close, the final lining with the sea was accomplished by dredging away the embankment in front of the dock entrance. On 26th July 1933, the world’s then largest graving dock was opened with great ceremony by its namesake King George V when the Royal Yacht Victoria and Albert with the King and Queen Mary onboard broke a red, white and blue ribbon stretched across the entrance. Later as part of the ceremonies Queen Mary emptied a cup of ‘Empire’ wine into the dock.

It wouldn’t be until 1934 when the White Star’s Majestic became the first ship to use the dock. The King George V dock would then on see a regular workload pass through the facility. Sadly, war clouds were gathering over Europe in the late 1930s and Britain slowly prepared for a possible war with Nazi Germany. During World War Two KGV 5 dock and the surrounding Southampton Docks was a prime target for Luftwaffe bombers and numerous bombs came close to striking the site that was seen as essential for ship repairs. The docks also played a crucial part in the preparations for one of World War Two’s most daring and audacious raids on German held territories, Operation Chariot.

The German blitzkrieg across Europe had secured for the Nazi’s vital ports along the Atlantic from which they could raid against Allied convoys and transports. One of the most important ports was the French port of St. Nazaire with its huge Normandie dry dock that was a contemporary of King George V dock. Like the Southampton dock it had been designed to accommodate the very largest French liners for repairs, but the dock could also be used to repair the battleships and battlecruisers of the German Kriegsmarine. It was a facility that the Royal Navy desperately wanted to deprive the Germans of exploiting. A plan was devised to conduct a Commando raid on the Normandie dock in order to destroy it or make it inaccessible for the German Navy.

The old obsolete destroyer HMS Campbeltown would be loaded with explosives and driven into the dock gates where it would explode while commandos would destroy pump houses and other vital facilities at St. Nazaire. Sailors, marines and soldiers came to the King George V dock in the spring of 1942 to practice how they could raid and operate St. Nazaire raid. The men practised descending the stairs of the pumping chamber in the dark and setting explosives against the pump mechanism. They also practised climbing inside the hollow caisson to set explosives and setting charges against the gate winding machinery.

Two years later with the war firmly in the Allies favour Southampton’s King George V dock was again utilised in the war effort when Bombardon breakwaters were built inside the dry dock that were used as temporary floating breakwaters to protect the famed Mulberry harbours of the D-Day invasion of Normandy.

Post war the fortunes of the King George V dock waxed and waned with a variety of operators using the facilities. Much of the ship repair work slowly shifted overseas and in 2005 Associated British Ports terminated the lease to A&P Group the last ship repairer to use the dock in its original intended use. Associated British Ports, however, decided to convert the dock into a permanent wet dock that saw it used in conjunction with the bulk-handling terminals at Berths 107 to 109, operated by Solent Stevedores.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item