TWO SHIPS BISCUITS

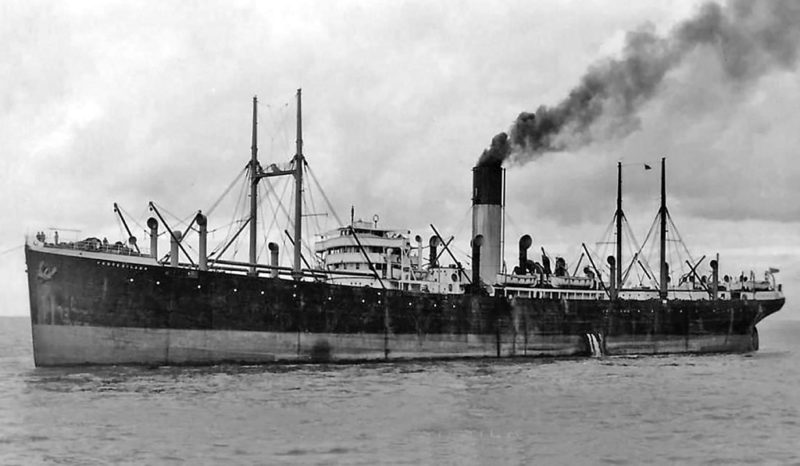

I was born in 1935 and we lived in a suburb of Swansea. From our house we had a sweeping view across Swansea bay. In 1940 I clearly remember seeing from our windows the two halves of the Protesilaus beached off West Cross. She was one of the first ships to be mined by an acoustic mine which in this incident was dropped off Mumbles head. The Protesilaus was Blue Funnel Line’s first 2nd world war casualty.

Swansea was from time to time bombed, which culminating in the ‘3 nights blitz’ in 1941. However about that time my parents evacuated me to a friend of my fathers who lived in a small cottage at Cartersford in Gower, 8 miles from Swansea. This was to be my home for the next year or so. I was staying with Mr and Mrs Percy Rees. Percy did only occasional work besides running his small farm, which was little more than subsistence farming on about 8 acres I well remember haymaking, the hay being cut with a borrowed finger mower pulled by a horse.

In subsequent years I used to cycle over and call and see them from time to time. Percy Rees died towards the end of the 1940s and one of the last visits I made to Mrs Rees shortly before she moved out of the rented cottage she gave me 2 ships biscuits that were wrapped in tissue paper. I had never seen them before. Both had paintings of a sailing ship on them, one in storm conditions, which has some damage and one a sailing ship in full sail. Unfortunately she did not give me any information about them and regretfully I never asked. Both were of a 4 masted barque. From time to time I would unwrap them to see them.

In 1952 I went to sea as an apprentice with H. Hogarth & Sons of Glasgow on the Baron Herries.

The years passed and I left the sea in 1960. In 1981 I unwrapped the biscuits and on this particular day with strong sunlight my wife looking at them said, “I can see a name”. Getting a magnifying glass we were able to pick out the name of the ship and the initials of the painter. With my interest aroused I wrote to the National Maritime Museum and in due course received some information and a photocopy of a letter that appeared in a nautical magazine of 1932. I now had a name to my ships biscuits. By 1997 I investigated further and in response to request for information I have been able to accumulate considerable information thanks to correspondence.

THE SHIP

The ships name was the barque Routenburn, one of Shankland’s all named after Scottish burns, in this instant the one entering the sea at Largs. The Routenburn was the last British built wool chipper. The initials on my biscuits were F.C.H., Frank Coutts Hendry. He commenced his apprentiship in the Celticburn in 1891 and was on the Routenburn in 1895 when she left Swansea on the 28th June that year. He wrote an account of his time in the ship called ‘Around the Horn and Home Again’. The junior apprentice on the Routenburn F.C.H. records, was a Percy Rees from Swansea. It can only be the Percy Rees with whom I was evacuated in 1941 and whose widow gave me the ship’s biscuits.

I did not know if F.C.H. was handy with the paint bush but conformation was to come from a person who had read my requests for information and kindly sent me a dust jacket for ‘The Yomah-and After’ which was illustrated by F.C.H. When F.C.H. wrote to a nautical magazine in 1932 it was to comment that in the November issue it recorded the news Hendry had been dreading for some time, the Routenburn, though she was now the Beatrice, was to be broken up. This was a ship he had had happy years in as an apprentice. This information was sent to me from the National Maritime Museum Greenwich.

The 2,097grt Routenburn was built in 1881 by R. Steele at Greenock for R. Shankland & Co. intended for the Australian emigrant trade and cargoes of wool on the home leg. It was recorded that she had one of the nicest figureheads of any British ship. She was sold to J.E. Olsen in 1905 and her name was changed to Svithiod. In 1922 she was sold to A. Pederson and renamed Beatrice by which time the height of mast and the square rig had been cut down and reduced from 20 sails to 15. She was broken up in September 1932 at Stavanger, hence the F.C.H. letter of that year.

F.C.H. THE SAILOR

Frank Coutts Hendry was born in Belfast in 1875. He joined the Celticburn on the 7th March 1892. He was on the Routenburn by 1895 when they sailed from Swansea for San Francisco on the 28th June 1895, with fellow apprentices Jack Boag, Percy Rees and two others. He completed his time in her, as he says, ‘The very fine four masted barque Routenburn’, and he obtained his 2nd mates certificate in Aberdeen. His new certificate in his pocket he travelled to Swansea where he had friends who might have influence in obtaining a berth. These were the days before the ‘Pool’ as the marine employment agency was known, but in Hendry’s time you had to walk the docks for employment. He also travelled to Cardiff together with Jack Boag and through a contact he was introduced to a master of a barquentine Kathleen of Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. The master told him that he did not normally take a 2nd mate only a boatswain but if Hendry did not mind hard work then he would take him. Hendry said he knew an able seaman who did not mind hard work as well, the Captain agreed also to take him. It seems that Boag had not got all his sea time in at this stage to sit for his certificate.

The Kathleen sailed from Cardiff with a full cargo of coal for Terceira, the eastern most Island of the Azores. Discharging was slow as no barges were available and fishing boats had to be used lifting only a ton at a time. During the time there the weather deteriorated and the storm built up to hurricane force. The barquentine was pitching on her anchors and she was dragging toward the cliffs and the final links of the cables were jumping over the whelps of the windlass. The ends of the cable were doubly secured around the foremast foot. Due to the pitching in head seas the cables had 60 fathoms out and one was grinding the spurling pipe (the pipe that carried the anchor cable to the deck) and the soft wood construction was disintegrating. Half a mile astern the seas were audibly crashing against the sheer cliffs. As the hawse pipe (the hole from the deck to the ships side) had gouged out a jagged hole in the hull they had to rig the towing cable to support the anchor cable and to take some of the strain. This worked and they weathered the storm. They sailed for Charlottetown and paid off in Swansea, Boag having got his sea time in, sat for his certificates, gaining his extra masters certificate and he joined Clan Line in 1903.

Hendry set up his home at Aberdeen and attended nautical college there and married. One day in 1897 walking the dock he ‘came up all standing’ when he saw a beautiful barque unloading nitrates from Chile. He had to go aboard and look around and in a few days signed on as 2nd mate. The John Lockett was sister ship to the J T North which John Masefield described as ‘the perfect J T North’ in his poem. He joined in Aberdeen and she loaded in the Tyne for Valparaiso, around the Horn in winter made the passage in 69 days close to a record. He paid off in Aberdeen and said goodbye to sail.

He taught navigation in Aberdeen, obtained his extra masters certificate, and obtained certificates in nautical and spherical astronomy (with honours) and in advanced naval architecture. About this time he was an officer in Cunards Ivernia. His desire now was to serve as master. He was aware that in many shipping companies it would take years to get command. It took Jack Boag 20 years in Clan Line to get command. However a ship master captain Jim Lingard on leave from Singapore told Hendry to go out to the Malay Straits and he would get a command in less than 2 years. The friend giving this advice had at one time had a chief officer who had never shaved had fluent Malay. He was to become the great writer Joseph Conrad. Hendry was convinced that Conrad’s Lord Jim was based on Jim Lingard.

1904 saw Hendry out east joining the ss Waihora as chief officer. The Waihora was Penang owned but a former Union passenger ship of New Zealand. Hendry said each officer had his own steward.

It was during this time he made local contacts and was offered his own command on the ss Flevo owned by Straits Chinese. Some 9 years since he had his first certificate and with youthful looks he was just under 30 years of age, but his new employer showed confidence in him. Not so his employer’s father, who felt his beloved ship was about to be lost. The former master had been unco-operative, unreliable and given to going missing when the Flevo returned to Singapore. Each time he had to be found and returned to the ship often having caused delays to the sailing. However he had excellent navigational ability and often boasted that if he was ever replaced then the next master would lose the ship. This had been put about Singapore at that time and the knowledge gave Hendry some unease, as had the old shipowner, but his son said they had to make the change.

The trade was general cargo out from Singapore to and around the Anambas Islands and copra and some sago back to Singapore. At that time the Anabas Natuna Besar and Natuna Selatan Islands were little charted and infrequently visited except by the Flevo. Because of this the owners were unable to get insurance on their ship.

On joining his ship he and the Eurasian chief engineer were the only two certified officers and non Asians on the 149 net registered ton vessel but with her smart appearance and white awnings she looked like a yacht. When Hendry took her to sea he felt that all eyes were on him to see how he handled her. From Singapore he consulted the chart and set course to pass down the middle of the Straits. The compass bearing was totally different to the ships actual heading and Hendry wondered what could be wrong. He checked the compass stand, then the quartermaster noticed Hendry’s puzzlement and said had he, Hendry, remembered to put back the red and blue rods, the magnets. It seemed that the previous master always took them out when the ship arrived back at Singapore and he put them back in when he went to sea again. Hendry had learnt his first lesson about the previous master, there were others to follow. On putting in the correcting magnets he decided to swing the ship for compass correcting. This done he proceeded with confidence and caution. On making his first call part cargo was discharged and some cargo taken on. On leaving and being pleased with his and the ship’s handling he was looking forward to the next Island Natuuna Besar. It was at this point that the chief Engineer said that it was an extremely difficult access through narrow reef passages and unmarked channels. Looking at his chart was little help as it was Dutch dated 1811 and many ‘Positions Doubtful’ were shown.

On arrival off the Island he went up the mast to try to find his way in. He could see some marks which did not appear to make sense, so he decided to anchor and make his own survey using his ship’s boat. He found it hard to pick the channel out from the reefs. Using that age old steam ship useful item, old fire bars, wire and shifting boards he set out to sound the channel and mark its course and the small pinnacles that protruded from the bottom to within a fathom or so of the surface. About half way towards the settlement there was a sharp bend, and although the previous master had marked it, his markings would not have given enough clearance on the bend, so the ship would have touched the reef edge. The previous master knew this and he made the necessary distance adjustment but that was only known to him. Hendry was 4 days surveying and charting his findings.

From Natuna Besar he headed for Natuna Selatan pleased with his achievements looking over the bridge at the flat calm green sea and clear blue sky his beautiful yacht making a respectable 10 knots. When suddenly his eyes were drawn to immediately beneath the ship, rocks were rising sharply up to the ship with weed and fish swimming around. As he leapt for the bridge to engine room telegraph and rang full astern, his thoughts were the loss of his first command after some 12 days. He thought that he would never get another chance and that he had not lived up to the trust the young Chinese owner had given him. He also thought that the waterfront in Singapore would be resounding to the joy of the former master and his friends when the news arrived. As the telegraph rang Hendry was surprised to see the chief engineer run to the bridge not the engine room as he would have expected. The chief engineer arrived on the bridge apologising for not having warned Hendry that on this part of the passage they always came across this ridge of rock but it never sounded less than 8 fathoms and they had come to know it as the ‘Aquarium’. With the vessel stopped all round all they could see were rocks red and pink coral weed through which were swimming brilliantly coloured fish. Still shaken, Hendry put the ship to full ahead again.

On passage from Natuna Selatan to Singapore and as they entered the Straits he could see far ahead on the horizon a very dark cloud that appeared to be developing for a thunderstorm. As he came more to the west the black cloud got bigger but now looked like smoke. Appearing also were masts and soon he was passing the Russian Baltic fleet on its way to destruction at the hands of the Japanese. Shortly after he arrived off the signalling station and he knew their arrival would be reported to his owners. At Singapore he put her in the same position that he joined her.

His young owner came out beaming with delight and reported that when the ship was first one, then two days overdue, his father took to his bed convinced by the fourth day his beloved ship had been lost, but now was overjoyed with his ‘joss man’.

Hendry left in 1907 after 2 years to become a Rangoon Pilot where he remained for the next 7 years.

F.C.H. THE SOLDIER

In 1914 he joined the army and was a Captain in the 4th Rajputd and served on the North West Frontier. In November 1915 Hendry was in General Townshend’s push to Baghdad and he was looking forward to triumphant entry to that city. The Turks stiffened their resistance and at the battle at Ctesiphon Hendry was wounded in the foot. He waited to be transported by cart and as he could not walk he was no use as a soldier. He asked if he could be of use to the navy, by now Townshend’s forces were in retreat and most were about to be cut off. Captain Nunn RN (afterwards Vice Admiral Wilfred Nunn, C.B.,G.S.I.,C.M.G.,D.S.O.) took up his offer and Hendry was taken by cart to the river to become Lieutenant F.C. Hendry, Indian Army, in command of the stern wheeler Mahsoudi flying the white ensign. She was one of six craft with instructions to proceed down the Tigris River with the general retreat. Over the next days the boats moved steadily downstream helping each other and the barges of wounded.

One evening as dusk was falling Hendry noticed what he first thought was another Arab was running along the hard mud at the river edge below the riverbank. But when he looked again the runner’s legs looked strangely white. Hendry got his field glasses looked again and it was a soldier dressed only in a shirt and his legs were white where his shorts and putties should have been. By this time the man was quite close and to stop for him Hendry had to turn his boat’s head to the river flow. He ordered the helm to port and increased the engine speed to make the turn. The soldier at the water’s edge thinking he was being left cried out, “My God sir! Don’t leave me! Don’t leave me”. Hendry assured him he would not leave him and to jump aboard when the boat came alongside. By this time it was dark and outlined on top of the riverbank there were a large group of armed Arabs. The soldiers in the Mahsoudi and its towing barges were watching the Arabs. There was a rattle of rifle bolts and one of the gunners shouted, “Jump mate” when the Mahsoudi was close enough to the bank. Hendry ordered hard a starboard and increased speed pulling the boat away from the bank. At this time the Arabs opened fire and shots were pinging everywhere. The petty officer opened up with the pom pom gun and in the gathering darkness the boat continued down river.

The rescued soldier now clad in navy gear was brought to the bridge to relate his story. He was in a column which had made a temporary stop and he and his mate found shade under a bush a little removed from most of his comrades, and when the order to move of was given they were missed. They awakened to find themselves surrounded by Arabs, the Arabs stripped his mate of his clothing so as not to spoil them and then cut his throat. At that moment this soldier had only partly been stripped when he noticed the mast and funnel of the Mahsoudi showing above the river bank, with a desperate burst of strength he broke away from his captors and dashed for the river bank. Hendry said that soldiers cry for help stayed with him all his life.

That night Hendry risked more night navigation to put greater distance between themselves and the Arabs. A few days later they came to anchor at Basra and Hendry’s 17 days Royal Navy service came to an end.

He became Principle Harbour Master at Basra and he finished with the war with OBE and MC, and was mentioned in dispatches 4 times. He returned to the Rangoon Pilotage for a further 7 years.

F.C.H. THE ARTIST AND AUTHOR

In 1923 Captain Hendry retired and in 1925 took up residence in Grantown on Spey Scotland and became a full time writer, using both his own name and sometimes ‘Shalimar’, recording his apprenticeship in ‘Around the Horn and Home Again’, many true and factious stories, reflecting his wide experience of the sea. Many of his short stories ‘Good Pilot’, ‘Through the Gap’, ‘What a Man’, ‘Almost an Ocean Mystery’ and many more were collected and published in book form. In total he wrote 18 or so books. Most were published by Blackwood & Son and for whom he was one of their most prolific writers, certainly in the marine field. Much of the illustration was done by Frank H. Mason R.I. some by Hendry himself.

Captain Hendry interviewed Captain E.W. Freeman when Captain Freeman was in retirement. As a result Hendry wrote ‘The Escape of the Roddam’. This was an account of the only ship to survive the pyroclastic explosion when Mount Pelee in Martinique blew up at 0745 on the 8th May 1902. The explosion was heard 250 miles away, and all excepting two of St. Pierre’s 38,000 inhabitants were killed. A passenger ship and a cable layer were lost. The Roddam had just come to anchor and the captain was about to ring ‘finished with engines’, when the super heated dust cloud began to fall. Captain Freeman called to the fore deck and shouted, “let the brake go free on the windless”. Someone did, as Freeman could hear the links of the anchor cable going out. He never knew who released the brake but that person saved the lives of some of his ship mates but not his own as no one on deck survived. Captain Freeman rang the telegraph, using his arms as his hands were badly burned, to full astern and as the ship was gathering seaway the cable was running out fast, the only hope was that the cable would break away from it’s mountings – it did!

The sea was beginning to boil as the gathered sternway ash was falling and burning awnings, boats and hatch covers. The steering had jammed so Captain Freeman could only get clear by using astern and ahead on the engine. After a time they were able to clear the steering gear. As all instruments and charts were destroyed, he used the sun through the dust fog, and headed for St. Lucia. The Roddam arrived there as little more than a smouldering hulk covered in thick grey dust.

Captain Hendry took a keen interest in his surroundings at Grantown on Spey. He loved the countryside and his knowledge extended to plants and birds in the area. He was also a keen fisherman in one of Scotland’s finest rivers.

He also took an interest in sport. During the Second World War he was largely instrumental in formation of the local Home Guard. He became President of The Grantown on Spey British Legion, he also took a keen interest in ex-servicemen’s welfare. He died in 1955 in his 80th year and is buried at Grantown on Spey’s cemetery.

Much of the foregoing was obtained from readers and responders to letters and help wanted columns, ‘True Tales of Sail and Steam’ Oxford University Press, ‘From the Log Book of Memory’ William Blackwood & Sons Ltd., Molly Duckett, manager Grantown Museum & Heritage Trust, Gavin Musgrove of the Strathspey & Badenoch Herald and the National Maritime Museum.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item