By Ernie Sabiston

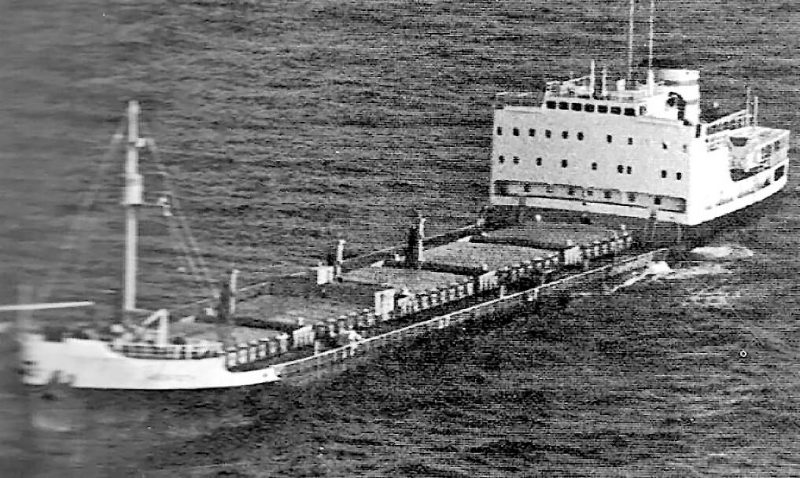

The Sunjarv started life as the Motor Ship Gjendefjell. She was built in the Sunderland Yard of J. L. Thompson & Sons in 1958 and was a five hatch gearless bulk carrier of 9,993 grt. Her owners were Dieseltank of Oslo, Norway, who sold her to Paddy Henderson’s British and Burmese Steam Navigation Company in 1965. They intended to charter her to Saguenay Terminals, a Canadian Aluminium Ore Company, who had several other ships on charter all named with the prefix ‘Sun’ and they intended to rename her Sunsalween. However, this never happened and she became the Sunjarv.

The Sunjarv started life as the Motor Ship Gjendefjell. She was built in the Sunderland Yard of J. L. Thompson & Sons in 1958 and was a five hatch gearless bulk carrier of 9,993 grt. Her owners were Dieseltank of Oslo, Norway, who sold her to Paddy Henderson’s British and Burmese Steam Navigation Company in 1965. They intended to charter her to Saguenay Terminals, a Canadian Aluminium Ore Company, who had several other ships on charter all named with the prefix ‘Sun’ and they intended to rename her Sunsalween. However, this never happened and she became the Sunjarv.

I had previously spent six voyages on the West African run on Elder Dempsters passenger ship RMS Aureol, and had asked the Company Superintendent if there was any possibility of employment on a cooler run. He vaguely replied that there was a 4th engineers position available on the ore carrier MV Sunjarv, presently berthed in Grangemouth, and that she traded to Mackenzie in Canada. Just the job for me, I said to myself after I had my brother Bill drive me the short distance to Grangemouth to have a looksee. Excellent accommodation for that time, and a shared toilet and shower with Archie, the Third Mate, a good natured fellow Scotsman. The engine room was well laid out and spotlessly clean, a legacy of the Burmese engine room squad who were hard, dedicated workers to a man.

John Hastie was the Chief Engineer who hailed from the Easter Road district of Edinburgh. Douglas Saunders was the Second Engineer, one of nature’s gentlemen and an excellent tradesman. He was a Manxman from Douglas on the Isle of Man, famous for its Manx cats, the moggies with no tails.

Bob Thompson was the Third Engineer, one of undoubted ability whose accomplishments included a supportive role in Scotland’s whisky industry. There being only three working engineers meant single handed watch keeping duties, something I looked forward to with a slight degree of trepidation.

The main engine was a 6 cylinder Doxford opposed piston engine, the same model which powered the Aureol, the only difference being the signage and instructions which were all in Norwegian. The generators were Bergen, an engine unfamiliar to me, but which were to prove very reliable. There was an electrician to ease the workload, and two Chinese fitters whose skills were to prove invaluable during the trip. They had been seconded from Blue Funnel Line, one of the companies which formed part of the recent amalgamation consisting of Elder Dempster, Paddy Henderson, Glen Line and Nederlandsche Stoomvaart Maatschappij Oceaan. The conglomeration was titled Ocean Fleets and were my new paymasters.

Bob Thompson had travelled from the village of Penicuik to join the ship. Penicuik was an outer suburb of Edinburgh nestled among the Pentland Hills and was famous, I think, for nothing. Bob had taken a taxi from his home for the twenty odd mile journey to Grangemouth. It seems likely now that some sort of rapport must have been established with the driver, for several refreshment stops had been made en-route, possibly at every pub. Bob was a professional whisky drinker and in support of his hobby had brought a case on board to keep him supplied until such time that the ship’s duty free spirits became available. I was invited to his cabin to partake of a noggin, and there in the corner of the sofa lay the recumbent form of a person obviously suffering from an overdose of conversation fluid.

‘Is this a mate of yours?’, I asked. ‘Och aye’ replied Bob, ‘it’s the taxi driver from Penicuik and he wants to come along for the trip.’ I could not believe it, could he be serious? What would the Captain say if he found a drunken taxi driver on board in mid Atlantic? Just in case, and with the help of the electrician, we managed to get the reprobate down the gangway and into the back of his taxi to sleep it off.

We departed Grangemouth on 10th August 1967, a date which coincided with the farewell party in Edinburgh for my brother Bill and his family who were soon to join the SS Fairstar to transport them to their new life in Australia. I was on the eight to twelve watch after we sailed, and about an hour later I noticed, with some trepidation and alarm, white metal particles adhering to the oily sheen inside the crankcase inspection window. This looked to be very serious so I immediately phoned the Chief Engineer who requested the engine be shut down ASAP. We anchored close by the Forth Rail Bridge and after the cooling down period the crankcase was opened to reveal the big end bearing had run its white metal lining. This bearing had supposedly been overhauled by a shore squad whilst the vessel was in Grangemouth, so it would now appear that they were somewhat less than proficient at their job. When these bearings are fitted with new white metal liners the clearances are checked by, what we called lead wool, not unlike lead string of various thicknesses.

The procedure was that the bottom half of the bearing was hoisted up onto the crankpin and flogged up with the top half to normal working conditions. The two halves had been covered with bearing blue and the crankshaft was now partially rotated and the two halves separated. The bearing blue indicated any high spots which were then removed by bearing scrapers. This procedure was repeated until an even surface was achieved and the clearance determined by the compression of the lead wool strips over the crankpin. This is usually a lengthy and arduous procedure, and if left unsupervised, it was not unknown for the shore fitters to roll a beer bottle over the leads to the required thickness and hung up for the surveyor to check with his micrometer. This was a distinct possibility in this case, so it was head down to fix it.

I was the only one on board who had carried out this procedure, having gone through a similar problem on the Aureol. The two Chinese fitters did a sterling job, doing most of the scraping and operating the three chain blocks necessary to handle the bearing half and most exhausting was the multiple flogging up and undoing of the four very large nuts which held the bearing together. It took 36 hours of hard work to rectify the situation, and what made it all the more vexing was the fact that while I slaving in the crankcase Bill’s farewell party was in full swing just across the River Forth in the Pilrig Halls in Leith.

Once we got the crankcase boxed up we weighed anchor and steamed down the Forth and out into the North Sea, heading north for the Pentland Firth, the stretch of water which separates the North of Scotland and the Orkney Isles. This Firth is infamous for bad weather, and extremely strong currents funnel through the Firth where the Atlantic flows into the North Sea and vice versa. Many Orcadians served in the Merchant Navy, sailing to every corner of the circular globe, and on their return home for leave, the weather conditions encountered in the Pentland Firth was such that many of these hardened seamen suffered mal de mer.

It was the only time in my career that I had the opportunity of sailing past my homeland and, with a lump in my throat and a beer in my hand, I could see the Hill on the Island of Hoy in the distance. We passed the North Western extremity of Scotland is Cape Wrath and in the late afternoon we left it astern and steamed out into the vast expanse of the North Atlantic.

I thought it might take about a week to get to Canada, and I mentioned this to Bob who replied, “Och no Ernie, its 16 days, and we’re no going to Canada, we’re going to South America”. “Hang on a minute”, I replied, “the Super told me we’re going to Mackenzie”. “Aye that’s right, Mackenzie is up the Demerara River in Guyana.” Well that was a bit of a shock to the system and I should have made sure of the destination before I signed on, but as Ned Kelly was finally to remark, such is life.

Danny Fegan was one of my tradesmen during my apprenticeship, and he had spent three years in the Merchant Navy to avoid conscription. He had visited the Leith Shipping Pool looking for a job, and there were plenty at that time. The various ship vacancies were displayed on a blackboard and the one Danny picked was going to South Georgia. Thinking this to be in the American Deep South and keen to get among the cotton pickin’ mamas, Danny signed on and spent the next six months in Antarctica, no cotton pickin’ mamas down there, only penguins.

All the vessels which were chartered by the Saguenay Aluminium Ore Company were painted green and had a rather undistinctive ‘S’ painted on the funnel. Our crew were all Burmese Nationals on twelve month contract, who had been seconded from Paddy Henderson’s British and Burmese Steamship Company. Although their exceptionally low pay rates were dictated by the Burmese Government they were never the less very hard workers. The highest rate was fourteen pounds ten, and the lowest five pounds ten per month. The Engineers Steward was named Minty O. O is a strange name in anyone’s language, and one of his more commendable attributes, compared with my erstwhile African Steward, was that he was free of the pernicious habit of drinking Guinness, especially at my expense. Indeed they were all, to a man teetotal, and I daresay their religion and pay rates encouraged no wasteful expenditure on alcohol. The food on board was excellent, including some top notch chicken curries served with crispy noodles, which were looked forward to with relish after a couple or three palate cleansing beers.

Les was the Electrician, and he had recently married and had his wife on board for the honeymoon. This in no way affected his primary role as Bob’s mate and drinking companion, being kindred spirits in the art of whisky imbibing. The crate of whisky was sadly depleted after three days, but we were then far out into the Atlantic Ocean and duty free supplies were available. There was plenty of excellent Scottish Tennents Lager in the bond, but the Chief Steward would issue none until the remains of the Embassy Club had been consumed. This was a disgusting American brew which gave you a hangover whilst it was being drunk, and had a taste compatible with gnats pee. Tennents Lager was the preferred brew throughout the Merchant Navy and it was mooted that if ships were fitted with sea bed sonar they could navigate anywhere in the world following the millions of empty Tennents cans which littered the sea bed.

The Captain’s name was Alan Ness and he cared naught for beer drinking, Pink gin was this man’s daily tipple, starting at Tiffin and continuing unabated throughout the live long day. He was a tall distinguished looking gentleman, with a thatch of snowy white hair, ruddy complexion and a fine command of the English language. His body was completely hairless, and the Chief Steward informed me that he regularly shaved it to keep it that way. I too shaved my body hair for a couple of days, as far north as the neck, in a successful endeavour to rid myself of an infestation of crabs recently contracted, at no expense, from the girl next door, who shall remain nameless to protect the guilty.

The Chief Steward, who also served as the Medical Officer, had prescribed American Army delousing powder to sprinkle on once the overburden had been shaved off. It worked like a charm, suffocating the little devils. I had sworn the Chief Steward to secrecy when I first consulted him about my freckles being on the move, and he promised not to tell a soul. The next time I went into the dining saloon for dinner the Captain shouted out, “How’s the lad with the crabs”. To add to my embarrassment the two grinning wives were at the table, so much for the pseudo Hippocratic Oath of confidentiality, this Scouse bastard will keep, I thought, making a silent vow to myself.

There were two women on board for the trip, the Chief Mate’s wife and the dear lady who had married Les, and was on her honeymoon. Their names escape me, and just as well I suppose, as they were both eminently forgettable. But this did not detract from the fact that I did not want my medical peccadillos spread around to all and sundry, and especially not to a couple of women.

I was on the eight to twelve for the whole voyage, and in the evening before tea I would venture into Bob’s cabin for a beer with him and Les. Invariably his pain in the neck wife would be there, “Oh and when do you work?” she would ask, and in a tone which suggested she thought I was lazy and only on board for the beer. “Eight in the morning till noon, and eight in the evening till midnight”, I would reply. The annoying thing was she asked me the same question every night without fail. This suggested to me that there was something amiss with this girl, especially in the memory retention department.

The honeymoon was going from bad to worse, and looked like turning into divorce or murder most foul. Les had taken to hiding in my cabin during my off duty hours to gain a bit of respite from her yapping, annoying me with his matrimonial problems, whilst quietly drinking to extinction my beer stash. She had already ripped up the wedding photographs and tossed them over the side. As a potential confidant and ally she could have turned to the Mate’s wife, but they were completely incompatible, having nothing in common except the English language. But even then the Mate’s wife spoke it with a distinctly higher class accent.

During the long engine room watches I was in the habit of doodling in a note book which was kept under the desk at the engine manoeuvring platform.

I came on watch one evening to find a note which Dougie had left on the desk, ‘keep your eye on the trykluft beholderer.’ I spent the next four hours unsuccessfully checking all the Norwegian name plates, and it turned out to be the main engine air start lever, which was located just beside our wooden desk.

The Atlantic Ocean, so often derided for its unpredictable and tempestuous weather, was the complete opposite during our crossing. Some afternoons I would walk up to the bow to watch the dolphins jumping in and out of the bow wave, attracted by the shoals of flying fish disturbed by our passing. On my way back down aft the Captain would invariably be on the bridge grimacing and shaking his fist at me, the reason being I had stopped shaving, from the neck up at any rate, and this was an example of the Captain’s aversion to body hair.

After the long haul across the Atlantic we made landfall at Trinidad. This was claimed to be the place that the Limbo Dance originated, but if truth be told it was invented by a Scotsman trying to get under the toilet door without spending a penny. The Sunjarv was based on this beautiful island, at Chaguaramas Bay which lay west of the capital, Port of Spain. Chaguaramas was home to an aluminium smelting plant, which converted the raw bauxite into refined alumina for shipping to North America.

Georgetown, the capital of Guyana, was an overnight trip south west, where we would anchor to await a high tide. Mackenzie, where the bauxite mine was located, was a hundred mile trip up the Demerara River, but the river depth, even at high tide, precluded filling the ship, so that two round trips had to be undertaken, a half load each time taken to Chaguaramas, discharged and back to Mackenzie for the second half. We were anchored at Georgetown on one occasion, awaiting the tide to proceed upriver. Some of the crew were going ashore in the lifeboat, and, much to my delight I was delegated engineer for the trip. Les had some urgent electrical work to complete, or so he shrewdly said, and that being the case, could I look after his wife on her trip ashore? Reluctantly I agreed, and off we went. Natural instincts impelled my skinny wee legs through the streets and into the welcoming bosom of a red lit drinking and horizontal refreshment establishment. Les’s wife appeared slightly apprehensive, but who was I to care? After ordering a couple of beers one of the bar girls came and sat on my knee, whispering lewd suggestions in my ear. Disgusted by my behaviour the wife got up and stormed out of the bar, and I thought to myself why should she, in the throes of a none too successful honeymoon, begrudge me a few beers and a bit of the same. Probably jealous, I thought, but when I got back to the ship Les was none too happy that I had taken his wife into a brothel.

Georgetown reminded me of an early Queensland town. Age old, stilted weather board houses, with mosquito netted sleep out verandas on all sides. Shady mango trees overlooking the dusty streets. Uniformed school girls sporting straw boaters, and uniquely attractive girls, tanned to a light coffee colour, lustrous waist length jet black hair. Surely some of the world’s most attractive women I decided, and later on did not one of them prove me right by winning the Miss Universe Contest! I mentioned, in graphic detail, their beautiful physiognomy and various other physical attributes to Bob on my return to the ship.

“Ernie ma son, never mind that”, he replied with single minded disinterest, “sit doon and have a nip o’ whisky”.

The Chief Engineer, John Hastie, had been my midnight companion on the long trip across the Atlantic. When I came off watch at midnight the more than slightly inebriated John would be waiting in his day room, whose door faced the engine room access, with a couple of beers in hand and a desire for a bit of a blether. Since we both lived in Edinburgh there was no end to the conversation topics, the soccer scene and the pubs and clubs, which went into the wee small hours depriving me of much needed sleep. Later on during the trip he decided to stop drinking, I think for health reasons, my own health included as his rambling midnight reminisces were giving me problems.

My normal watch keeping hours were four on and eight off. During the couple of weeks the ship was shuttling between Trinidad and Mackenzie the duty watches were then eight on and four off. The reason for this was that when the engine room was on standby there had to be two engineers on watch at all times to operate the engine controls and auxiliaries, which meant two hours before and two hours after each regular watch. My duty hours were now six ‘till two, morning and evening, in addition during my time off it was part of my duties to sample and test the condition of the boiler water, maintain a record of the hours run and maintenance performed on the generators and look after and record a log of the refrigeration plant.

One afternoon at two thirty the Sunjarv anchored halfway between Georgetown and Mackenzie. I had just completed my first eight hour shift for the day, collected a couple of beers from the bar, and was leaning on the boat deck handrail watching the crew bartering with the local natives who were tied up alongside the ship in their canoes. The natives bartered fruit and carvings and a clear coloured mellow rum with a distinctive flavour, reminiscent of Philippine Tanduay Rum. The bartering currency was cigarettes, of which we had an abundance at a shilling a packet.

Suddenly, “Hey mister!” followed by a sharp poke in the back, “Did you leave the engine room with one of the purifiers running?” “Yes I did Chief,” was my reply. “Well get back down there until I tell you different.”

This was John Hastie at his sober best, his true nature shining through at last. Completely different now from the likeable Easter Road bloke I had come to know through countless midnight soirees, devoid of the veneer of companionship induced by alcohol, inarticulate through the lack of conversation fluid. I ran into him again about four years later in the Mercantile Marine Office in Leith. I had sworn revenge on this man, but as he stood there chatting, wearing neatly pressed cavalry twills, hush puppies and a dark blue blazer resplendent with a Hibernian F.C. emblem, I could only tell him to **** off in the most agreeable manner. All my dreams of head butting, ball kicking and manual strangulation washed away in a sea of pity for a very ordinary little old man.

Once we had completed the double loading of alumina at Chaguaramas we set sail for Mobile, Alabama. It was about a seven day trip, blessed with exceptionally good weather up through the Caribbean Islands, past Jamaica and the Cayman Islands and through the passage separating the western tip of Cuba and Mexico, and into the Gulf of Mexico. After our arrival in Mobile the American Customs and Immigration came on board to issue identity cards to allow the officers and crew to go ashore. During my interview I was obliged to sign a form in which I promised not to try to overthrow the duly elected Government of the United States! This seaman’s identity card was also necessary as proof of age and identity as the drinking age was twenty one, and although I was twenty two my appearance belied my age as I looked younger. This became obvious as I was asked for my card in every bar I visited.

We had a passenger come on board for the trip up to Baltimore, and then the return voyage to Trinidad. He was a pleasant gentleman of nondescript appearance, with a liking for beer drinking, a kindred spirit it could be said, and after the first can of Tennent’s Lager he was hooked. He would prove to be good company, and eventually very reluctant to leave the ship in Trinidad.

After leaving Mobile our course took us around Florida’s Key West and north past Cape Canaveral during which time we were continually buzzed by American fighter planes. It was assumed that the Americans did not want foreign ships anywhere near their NASA centre. Cuban boat people were also on the American watch list and there were plenty of them. The lights of Miami were visible as we made our way north with the Bahamas on our starboard side. Our arrival into Chesapeake Bay was a bit of an eye opener. There was the bridge/tunnel crossing the bay with the traffic disappearing into the tunnel as we sailed over and coming up the other side. Once we got docked in Baltimore we had tour operators coming on board offering trips to Washington, evidently only an hour’s bus ride away. I had contemplated taking the trip but decided to go on a drinking expedition around the local bars rather than visit the White House. There were also magazine subscription salesmen on board and I foolishly ordered a twelve month issue of the Playboy Magazine and I’ve yet to receive the first issue.

After the discharge we set sail once more down the eastern seaboard and through the Caribbean Islands to Trinidad which is the southernmost of the Islands and virtually only a stone’s throw from the coast of Venezuela. On the eastern side of the island is Manzanilla Beach, a location made famous by the Andrew’s Sisters with their famous ‘Drinking Rum and Coca Cola’ song.

The Captain was informed en-route that the ship was to load a full cargo of alumina consigned for Rotterdam. In addition, the crew’s twelve month contract was completed and they would be paid off on arrival and a replacement Burmese crew signed on. On arrival at Chagauramas we anchored off as the loading berth was occupied. This came much to the delight of our beer drinking passenger, another couple of days on board before he was obliged to depart.

Once the berth was vacant, we upped anchor and proceeded to dock. As we were loading the alumina we bid a tearful farewell to our American friend. A taxi took him to the airport for his trip back to Mobile. With a full load we set sail for the long drag across the Atlantic bound for Rotterdam. This was somewhat of a relief for me as I could feel that the last shreds of my sanity were about to part. It was becoming increasingly difficult to get Bob out of bed at midnight. His huge whisky consumption was rendering him comatose, and it took jugs of water and wallops with an empty whisky bottle to get him to display any vital signs.

“Och I’m awful sorry Ernie,” he would mumble coming on watch at one in the morning. “It’ll never happen again.” He said this every night, but he was a likeable fella all the same.

I was on the engine controls when we arrived to pick up the Rotterdam Pilot. The appearance in the engine room of a Dutch scrap metal dealer was a bit of a surprise. He had come on board with the Pilot, and was looking for scrap non-ferrous metal ‘Where’s there’s muck there’s brass’ according to the old English adage, and there was plenty of brass here. This was an added bonus for the engineers, in Dutch Guilders, as we all shared in the proceeds of the scrap deal, with the exception of the Chief Engineer, who had no knowledge of these nefarious transactions. Most of the scrap was old, but quite a lot of the heavier items still had the labels attached.

I had on the homeward voyage repeated requests from the company to do another trip on the Sunjarv, and had repeatedly declined. This eventually led to John Hastie informing me that there would be no continuity of employment, if not on this ship. ”I’m getting off in Rotterdam,” I told Hastie, “and you can stick the ship, the job and the company.”

On the 27th October 1967, an overcast, rainy Dutch day, we signed off the Sunjarv and the shipping agent took Bob and myself out to Rotterdam Airport to catch the flight to London. It was a propeller driven aircraft, and somehow Bob had managed to obtain and drink two miniature bottles of whisky even before we took off. A sympathetic hostess had supplied the grog, against regulations, and this was a bloody relief to me as the box of chocolate liqueurs I had bought for Mum had been under the ever thirsty scrutiny of Penicuik Bob. I had a drink with Bob during the flight, and was slightly confused and unsteady when we landed in London.

I sent Dad a telegram announcing my impending return, but in the aftermath of the whisky drinking, I had neglected to mention date, time and place of arrival, so I was a bit bemused when I disembarked at Turnhouse Airport to find nobody there to meet me. I thought that if I have to get a taxi I will go to the pub first. I did, and it was only when I eventually arrive home and had a look at the uninformative telegram that I realised the error of my omission.

The aircraft which had sped me from London to Edinburgh was a De Havilland Comet, which had the distinction of being the first passenger jet aircraft. It was now coming to the end of its service life, and I was surprised at the small interior compared with the Boeing 707s which were replacing them, but never the less was glad of the opportunity to have flown in one.

The Sunjarv carried on trading for the next nine years until 1976 when, for reasons unknown, she sank after springing a leak in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of South Carolina while on a voyage from St. George’s Harbour, New-foundland to Savannah with a cargo of Gypsum. The crew of 20 took to the liferafts and were rescued. At the time she was owned by Atraz Shipping of Fama-gusta and named Aegis Duty.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item