The Bendoran

It would not, I feel, be an exaggeration to say that thirty days in the year 1966 changed my life and altered forever my vista of the whole world. For most Englishmen the year 1966 conjures up one thing only, the World Cup. For me however, it was the unbelievable opportunity to see vast new chunks of the globe that I had hitherto read about only in geography textbooks.

It was early May in 1966 and I had just got back from school at about five o’clock. My father was a Radio Officer with GCHQ and over the tea-table he told us that he had been posted to Hong Kong and would sail from London’s Royal Victoria docks on the 23rd July on the SS Bendoran of Ben Line Steamers.

“Is it a big liner, Dad, like the Queen Mary?”

“Er, no. It’s a cargo boat with cabins for only eight passengers.”

I honestly thought he was joking.

“Eight? If there’s four of us then who are the other four?”

“I’ve no idea. How would I know? We’ll have to wait and find out, won’t we?”

“We’re going to miss the World Cup final, Dad. That’s not fair.”

“So what? You don’t think England will get that far do you?”

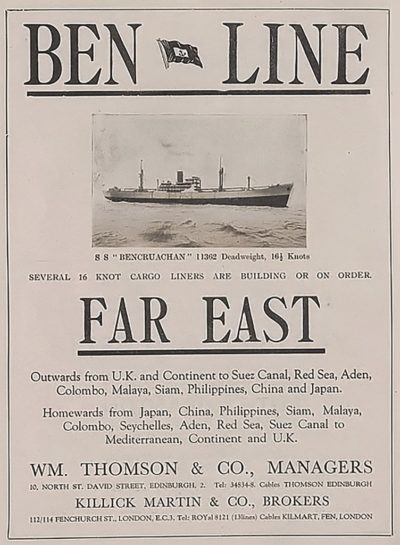

Had the internet been available in 1966, I would almost certainly have done some research on the Ben Line in general and the Bendoran in particular before we sailed. I would have learnt that the Ben Line was founded in 1825 by two brothers, Alexander and William Thomson (note the Scottish spelling) who set up as shipbrokers in Leith, the Port of Edinburgh. They acquired their first ship in 1839 and within twenty years had demonstrated the viability of trading with the Far East. They never looked back. The company’s first steamship was named Benledi after a mountain in Perthshire and by the end of the 19th century all the company’s vessels were named after ‘Bens’ the Gaelic word for mountains. The Company though combined the two words so Ben Ledi became SS Benledi. This was probably so as not to confuse it with mountains of the same name, but one amusing anecdote had it that being Scottish and canny with money, it would cost less to cable or telegraph one word rather than two! Whether that was true or not I don’t know, but it makes an amusing tale.

The weeks just flew by. But a potentially disastrous problem had cropped up which could ruin our hopes. There was a shipping strike! The National Union of Seamen had called the biggest-ever strike of its members. Fortunately the strike was called off about three weeks before our sailing date.

On the afternoon of Saturday 23rd July we arrived at Royal Victoria Docks. I had never seen so many ships in my life. Not even in Grand Harbour, Malta where we used to live. Looking up at Bendoran from the side of the quay she looked huge. The blue grey side of the hull seemed to tower above us for ever and cranes were still loading cargo into the forward holds. It would be another ten days before we found out exactly what that cargo was. I don’t recall going through any immigration formalities at all. Stewards appeared out of nowhere to take all the cases and we followed a welcoming crew member up a very long stepladder leading to the port side accommodation deck. A smartly uniformed Officer introduced himself to Dad. My great adventure was just starting and I was not to step foot on Britannia’s soil again for over three years.

Two other passengers made themselves known to us. Rosina Cave and Evelyn Broadbent were in their early twenties and were Foreign Office secretaries heading first for Singapore and then Kuala Lumpur and Rangoon respectively. They proved to be excellent company over the next four weeks. We were informed there was one other single male passenger but he was nowhere to be seen.

We had dinner in the splendid dining room and met some more of the ship’s officers. Departure was scheduled for ten o’ clock and I decided not to wait up and turned in. The cabin I shared with my sister Linda was huge. I think Mum retired as well but Dad stayed up late as he wanted to see Southend Pier as we sailed down the Thames Estuary towards the Channel and the Dover Straits. It would have brought back many boyhood memories for him as Southend was a favourite day out from the home in Edmonton, North London.

The next morning was Sunday 24th July and we had breakfast about 9am, the attentive Chinese stewards attending to our every need. I felt very important. Linda and I had a table all to ourselves but Mum, Dad and the two girls were always seated at one of the two Officers’ tables. They were all very smart in their ‘whites’. There were two or three young looking chaps in their late teens and only a few years older than me. They always smiled when spoken to but I couldn’t understand a word they said! A few days later the Captain told me that the young crew were cadets from the Shetlands and they spoke Gaelic and only a smattering of English. So that explained it. There was still no sign of the mysterious seventh passenger.

The Bendoran progressed southwest towards the Bay of Biscay. Daily, the Officer of the Watch posted the ship’s noon day position on a little slip of paper that was attached with four drawing pins to the Passenger Notice Board outside the nicely appointed passenger lounge. Dad being ex-Royal Navy had bought me a Daily Telegraph map of the World and ordered me to mark the position on the map every day before lunch.

“Make sure you get it right, boy. No sloppy navigation.”

Evelyn and Rosina were very good company and although they were much older than my sister and me, we mixed easily. The crew showed us how to play deck quoits and we took to it with alacrity.We were starting to get our sea legs and just as Dad had said it got a little choppier as we rounded Brittany and headed out into more open waters. The weather was fine and you could feel a warmth in the air as the latitude figure decreased.

On the Monday our seventh passenger appeared for breakfast. I couldn’t believe it. He was an Irish priest! Why couldn’t he have been a famous footballer or a film star? How on earth was a thirteen year old adolescent going to strike up conversations with a priest? I ask you!

It was customary to take coffee in the lounge about eleven o’clock he took the opportunity to introduce himself. He shook hands with us all in turn.

“I’m Patrick Corcoran but please call me Paddy. Everybody else does.”

So we did. He glanced down at the small table where my father had put his coffee cup, an ever present ash tray and a paperback book that he was currently reading. Paddy glanced down at the title and smiled.

“Are you enjoying the book or is it tough reading?’”

Dad was slightly puzzled until he also looked down at the front cover. Unbelievably it was called ‘The Tight White Collar’. Everybody laughed out loud, you just couldn’t make it up. The ice was broken. From that moment on our little group of six became seven and it reminded me of the ‘Secret Seven’ book series, one of my favourites at that time. Everybody looked forward to the next four weeks. There were adventures ahead that it was perhaps best not to know about just yet.

On the fourth day early in the morning we approached the Straits of Gibraltar. The Rock stood gleaming in the brilliant sunshine.

“With a bit of luck we’ll see some dolphins”, announced Paddy who had done this voyage before on another ship of another line.

Sure enough a small pod of ‘Flippers’ soon joined us as they rode the ship’s bow wave but sadly they didn’t stay with us long. Anyway at least I had seen my first dolphin.

A few hours later the duty Officer affixed the noon day position and Dad had a brief chat with him. Looking back it must have been a poignant moment for Dad as the Bendoran was now at its closest point to Oran, Algeria and the port of Mirs el Kbir. Twenty six years earlier in 1940 he had been a leading telegraphist onboard the battleship HMS Resolution when it had been torpedoed and badly damaged by a Vichy French submarine. Some of his shipmates died when two ‘tin fish’ went into a mess deck.

The ship ploughed on at its best speed of 17 knots. In 1966 that was very fast for a cargo boat. The Ben Line’s owners, the Thomson family of Edinburgh, did not skimp on investing in new marine technology and their vessels incorporated all the latest designs and innovations that money could buy. Most of the Line’s vessels were built on the Clyde and the engines supplied by Glasgow engine manufacturers. Bendoran was built in 1956 by Charles Connell & Co. Ltd. and her two steam turbines were supplied by David Rowan Ltd. Both companies represented Glasgow’s finest. The one thing I do remember well is that Bendoran was a very quiet ship with almost no vibration. One day the ship’s Chief Engineer gave us a tour of the engine room. “She’s as quiet as a moose”, he told us in broad Scots brogue. Years later this was confirmed to me by a chap called Peter Skelton of whom I will write a little more later.

Our next noon day position found us about twenty miles north of Gozo, Malta’s sister island. Being born there in 1953 I had rather hoped that we would sail just south of Malta so we could see the giant Jurassic cliffs that form its western and southern coastline but it wasn’t to be. However Dad had another idea. He went up topside to speak to the Marconi trained Radio officer and asked him to send a signal to a colleague of his, Jim Burtoft, who he hoped might be on duty at the Admiralty radio station at Dingli I recall the signal read something like this:-

“onboard ss bendoran en route to hong kong stop we should be within twenty odd miles off malta at closest point stop regards to all on duty stop vic harland message ends”.

To our amazement just after lunch the radio officer came into the lounge waving a bit of paper which read:-

“hello vic stop chased all round the island looking for your stack’s smoke but no luck stop bon voyage stop jim message ends”.

Imagine some GCHQ staff trying that today! Mind you the age of the internet, emails and Skype makes those old radio sets with morse code redundant. That’s probably just as well because I can’t imagine some Harry Potter lookalike decrypting a cyber attack being any good with a Morse code key or a flashlight. Can you?

The next day we passed south of Crete and headed on a bearing of about 100 degrees towards Port Said and the entrance to the Suez Canal.

The Saturday afternoon, 30th July, found as at anchor a few miles off shore in shallow water. We were not alone. It seemed like we were surrounded by ships of every description all riding at anchor in a stiff breeze. I spotted tankers, a small white hulled passenger liner and many others, over twenty in total.

The third mate was a Brummy and the only English officer aboard. I asked him what was going on and he explained that we have to go through the Canal in convoys and that we would not be entering the Canal until the next morning.

“Don’t forget to listen to the World Cup Final.”

Despite my Dad’s earlier gloomy prediction England had indeed reached the Final and were playing West Germany at Wembley. I was furious that unlike all my mates back home I would not be able to watch it. In 1966 there were no TVs on ships and we would have to settle for listening to it on the BBC World Service. There was a huge wireless in the lounge that boasted every waveband possible. It had proved a magnet for Dad who had already fine tuned it to the right spot to listen to the match. So important was it that the Chinese stewards had already changed the dinner time for the day. Allowances were made for the fact that we were three hours ahead of GMT. I seem to remember that dinner was at the silly time of five o’clock so that we could finish eating by the six o’clock kick-off time.

The game started badly for England with West Germany scoring first. As we all know England were the eventual winners. Kenneth Wolstenholme’s words, “they think it’s all over…it is now!” passed into folklore but I honestly don’t remember that as we craned our necks towards the radio. Maybe it was a different commentator on the radio to TV. Believe it or not I did not actually see any film of the game for over three years

The movement of the ship woke me up just after dawn the next day. I drew the curtain and looked for’ard. We were moving into Port Said. The big day had arrived at long last. I got dressed and raced down two ladders to the dining room. I ate breakfast in record time. I didn’t want to miss anything. Up on deck the scene was fascinating. There were fast moving small boats and ferries seemingly moving in every direction. Although a Sunday, in Moslem Egypt this was a normal working day. I guess it was about eight in the morning and thousands of people seemed to be going to work by boat. It was noisy with ships’ horns and hooters going off all the time. I could see several domed mosques and I was taken aback by the sheer loudness of the call to prayer being shrieked from a minaret just yards away from the ship. We were moving very slowly but small boats came alongside and traders climbed up ropes and ladders to ply their wares to passengers and crew alike. Dad bought some oranges and a pair of camel hide sandals that were as hard as concrete. He kept them for years much to my mother’s disgust. To my amazement Paddy bought a length of fishing line together with several hooks. I didn’t ask him why.

Not long after an officer arrived and shooed the traders off the ship. “Bloody Gypos!’” Nobody was politically correct in those days. A pilot had come aboard from the Suez Canal Authority as was the usual practice. I saw him clamber up a rope ladder to be met by an officer who immediately took him up to the bridge which was somewhere I hadn’t been encouraged to go yet.

We very soon realised that we were now in the canal itself and that there was a small tanker ahead of us and another freighter close behind. It wasn’t nearly as wide as I thought it would be. Bendoran picked up speed, probably to about eight knots. All you could see in any direction was cultivated land and it was much greener than I had expected, despite being in the middle of summer. There was something like a tow-path down both sides of the canal and you could see the occasional vehicle and quite a lot of camels. Dad’s cine camera was getting an airing and he filmed everything that moved. For the first time I felt as if I really was heading East. The captain had said it was OK for me to make my way forward to the bow and for a long time I perched myself at the very tip, clinging on to the flag staff for comfort. Unfortunately Dad spotted me from about 200 feet away and later chided me for going ‘off limits’ but calmed down when I told him the Captain had agreed. I took a couple of photos to post back to my geography teacher, a Mr Lawson.

‘Brummy’ had spotted me and on my return to the main passenger deck had shouted down to me in his broad Brum accent, “Great stuff England winning the World Cup eh.’” Then it dawned on me why none of the other crew had mentioned it. They were all Scots!

It was about coffee time and I took a closer look at a map of the Canal Zone that was available in the drawer of the writing bureau in the lounge. Navigating Officer Corcoran pointed with his forefinger.

“We’re about here Mark. We’ll be sailing past the town of Ismalia soon past Lake Timsah and then into the Bitter Lake where I bet you we anchor for while.”

I asked him why and Paddy ran his finger further down the map.

“As our convoy heads south another convoy heads north from Suez and we pass in the middle so to speak in the Bitter Lakes.” Until that moment I never knew that. It’s amazing what you can learn from a priest who drank eight tins of Harp a day.

“That’s why I bought the fishing lines. I’ve two rods but no line. We might be anchored for a few hours and it will while away the time.”

We didn’t know it at the time but that was a gross underestimate. Just after lunch an Officer brought us bad news. A Norwegian tanker sailing ahead of us in the convoy had miscalculated one of the many bends in the Canal and had poked his nose onto a sand dune. They were sending a tug up from Port Tewfiq at the southern end of the Canal to tow him out. An hour or two later and we anchored in the Bitter Lake just as Paddy had said. The worst bit was we had no idea how long we were going to be stuck there. It was hot, really really hot. Paddy had disappeared but I eventually found him on the poop deck near the stern. He was fishing! He must have been boiling in his black surplice and that white collar.

“So there you are. Grab the other rod.”

We waited in vain for the first bites and Paddy entertained me with stories of fishing for trout in the Blackwater River back in County Cork.

We could feel the first nibbles on the hooks baited with a bread paste that Paddy had mixed. Paddy caught the first one, then another. He took them off the hook and threw them onto the deck but one of them kept flapping about.

“It’s still alive I said.”

“Well pick it up and bash its head on the deck.”

I hesitated and Paddy propped his rod against the rail. He bent down, picked the fish up by its tail and banged it hard onto the teak deck. Wallop! He crossed himself theatrically and I grinned.

“Shall I pop them in the bucket Paddy?” innocently believing that the white bucket was for the fish which had some ice in although it was melting fast.

“Er no.”

I peered into the bucket. It had tins of Harp in it!

I asked him if he had seen my Dad who I hadn’t seen since lunch. Paddy replied that if I could say that in Latin he would give me a tin of Harp. That was easy. So I thought.

“Ubi est meus pater?” I said with supreme confidence.

“Wrong. It’s ubi meus pater est. The verb always goes at the end Mark. You should know that.” I didn’t get the beer.

I recall we caught about a half a dozen fish all about a foot long. Paddy gave them to the Chinese crew who he assured me would cook them that evening.

Dusk and dinner came and went and we all retired to bed. It was so hot. Maybe with the engines off only standby generators were being used for the air conditioning. By breakfast time we were still in the same spot. The Captain was agitated and said he had no idea how long we were going to be there. I asked him if it was OK to take a swim as I had noticed that a gangplank had been lowered on one side down to water level. He immediately forbade it. I was shocked. Until then he seemed a nice chap.

“I know it’s hard to believe but I’ve heard tales of sharks both in the Canal and the Bitter Lakes. So I’m sorry the answer is no.”

A year later I borrowed a book on sharks from a library in Hong Kong and there was a whole chapter on the mysterious ‘Suez sharks’ that seemed to thrive in the brackish waters of the Bitter Lakes. It seems that after the Canal was built in the mid-nineteenth century some sharks had found their way from the Red Sea up into the Lakes, had thrived on the available fish and mutated into a sub-species that was happy in the low salinity waters. I shuddered when I read that bit. The Captain’s advice had been sound.

Altogether we were stuck in the Bitter Lakes for almost two days. The next morning Bendoran was making 17 knots in a SSE direction. The next stop was Aden, a British Protectorate in South Yemen. There we would bunker only without disembarking. It was a dangerous place. In fact very dangerous.

The next day’s noon position brought us on a level latitude to Mecca and the port of Jeddah although we could could not see the land through the heat haze. I was not to know that twenty years later I would find myself working in Jeddah for a financial services company. That afternoon brought forth a little bit of excitement. The Captain’s son was a cadet on another ship of the Ben Line. From memory I believe it was the mv Benledi, a more modern and much faster design. The Benledi was also in the Red Sea and heading north towards the Suez Canal. The Masters of the two vessels had prearranged to pass close to each other on reciprocal courses so that they could see each other on deck and speak via VHF radios. It proved to be quite an occasion and we could clearly see our Captain’s son on the bridge wing of Benledi. With the two vessels making forty plus knots between them it was over all too soon. I reckon the ships were about 200 yards apart at the closest point, about the same as the length of Benledi. Both ships sounded off their horns in a cacophony of celebration. For our Captain it must have been the highlight of the voyage.

Two days later I was awoken by some severe banging on the cabin door. It opened a little and a voice said, “Mark, get dressed and come up onto the bridge.” It was Brummy.

A couple of minutes later I was behind the bridge in another smaller space gazing at a horizontal flat glass screen that was almost as big as a dustbin lid. It was a radar! Brummy pointed at a yellow blob that illuminated as a clock like winder passed over it. He was excited.

“See that blob? That’s the Eagle, an aircraft carrier!”

“How do you know?”

“I’ve been listening to it on VHF radio. I heard the pilots talking before they landed. They’ve stopped flying now. Must have been a night flying exercise.”

It was just light and probably about six maybe seven o’clock. The blob disappeared from the radar screen as it steamed out of range of the equipment. We never did actually see Eagle, only its radar blob. I was so disappointed. The only other ship I had ever been aboard in my life had been the American carrier USS Shangri La when she had paid a port visit to Grand Harbour, Valletta in 1962. Oh well never mind. In fact I did see Eagle but not until she visited Hong Kong in 1968. Two hours later, just after breakfast, we steamed into Aden.

If the good Lord ever wanted to give the planet Earth an enema he should stick the tube into Aden. This British Protectorate had been a hotbed of violence and political unrest for years. It was only a matter of time before Britain pulled out but until then thousands of British troops and a Squadron or two of Hawker Hunter fighter bombers were all that prevented “FLOSY” (the Front for the Liberation of South Yemen) from imposing their own will on a small, rocky, bone dry, hot hellhole whose only asset was its strategic position at the southern entrance to the Red Sea and the Suez Canal.

Bendoran rounded a point and I remember a tall clock tower coming into view. It seemed totally out of place in the arid landscape. We tied up to two buoys in an area called Steamer Point. Contrary to what we had been led to believe not only were we allowed to go ashore but we were told by ship’s officers that we had to! I was excited and Dad was pleased as he wanted to buy a camera. Paddy had told him that Aden was all duty free and he could pick up a bargain. Mum, Evelyn, Rosina and Linda looked apprehensive already and even more so when we clambered down the gangway and got into a motor boat that had come alongside. It was only a few minutes’ journey to a jetty that had a canvas awning over much of it to provide shade. It was awfully hot. There were soldiers everywhere and I immediately recognised the tartan kepis of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. They had been stationed at Tigne Barracks in Malta three years earlier and I had ridden in their three ton Bedford trucks every Tuesday to Scouts.

A Warrant Officer immediately started chatting to Dad and Paddy but I couldn’t hear what they were saying. Suddenly out of the blue an Army staff car appeared. It was open top and an officious looking man got out and started walking towards us, he was not happy.

“Get those effing civilians back on that effing ship immediately! What are they effing doing here?!”

One of Bendoran’s deck hands who had come in the boat with us intervened. His name was Jim Martin and he looked the Army Officer straight in the eye and pointed towards Bendoran which by now was flying red flags all over it. What was all this?

“You see those red flags pal? That means we’re unloading ammunition for youse, pal. OK pal?”

The Officer was taken aback at being addressed in this manner but Jim was not taking the Queen’s shilling and he could say what he wanted.

“I see. Well in that case I have to tell you that as British subjects I am responsible for your safety. I was not made aware there were any civilian passengers onboard. I will detail some men to accompany you until you re-embark. When will that be?”

Nobody knew but before he drove off the bombastic Officer detailed a platoon of Argylls to stick to us like glue until we headed back to the safety of Bendoran. From memory about a dozen soldiers did exactly that for about the next six hours.

So at that point we knew why we had to disembark the ship. Until then we had no idea that we were carrying tons of munitions for the Army. We later learnt that the shipping strike had caused horrendous problems for the Army and probably the RAF too. They were literally running out of ammunition for the Centurion tanks and (appropriately) the ADEN cannons on the Hunters. You could only take so much material by air and the Argosy cargo planes of Air Support Command were probably at full stretch. It seems like Bendoran was the first British registered cargo vessel heading to Aden since the strike ended that had some spare capacity to carry badly needed munitions. Hence the attitude of the officious Officer at the quayside.

“So what do you people want to do?’ asked a friendly Corporal.”

Paddy explained that the girls wanted to buy some perfumes, Dad a camera but that he would prefer to go to the Seamen’s Mission which he had visited before on previous transits through Aden. The Corporal waved and gestured towards an Arab gentleman probably aged about sixty who left the other Arabs he was talking to and walked over to join us. He spoke good English and said he was a British subject (yeah right!) Dad gave him a Gold Leaf cigarette and lit one for himself.

“I will be your guide’ he said. One pound each. Seven people, seven pounds. OK?”

We set off walking towards a built up area with six squaddies in front and six behind, all armed with the standard NATO Belgian rifle. They all wore khaki shorts, long socks, black boots and of course the highly visible tartan kepis. The ladies were all in summer dresses and Dad and I in white shorts with long socks. Paddy was all in black with the exception of his white collar. What a disparate bunch we must have looked. Like something out of a Python movie! We reached a shop that the guide said sold perfume.

“Just a minute’ barked the Corporal”, and he instructed three of the front six soldiers into the shop first. They came out a few minutes later.

“All clear.”

It was a routine we fell into wherever we went. The Corporal insisted. He knew his stuff. He told us that FLOSY was taking more and more risks and more and more lives.

“They’re bloody everywhere pal, I’m telling you. Effing bastards all of ’em.”

The guide led us to a camera shop. Same routine as before, Squaddies in first. We soon heard a noisy kerfuffle inside the shop and two more soldiers rushed in. They came out dragging an Arab by his legs. He screamed at them and pulled a kris, an Arabian curled blade dagger, out from his garments and swished it towards the legs of the nearest Argyll. Big mistake. Two seconds later the butt of a heavy L1A1 Belgian rifle came crashing down on his head. Lights out.

“Sorry about that”, said the Corporal and he radioed for backup.

It wasn’t long before a Land Rover arrived and the miscreant was chucked in the back still unconscious. We went into the shop and Dad after much haggling bought a Zeiss Ikon 35mm camera. I still have it today. It cost £17! He also bought four rolls of Agfa film which he thought would last the trip. A coin was tossed to see if they would be free or £3 as the shopkeeper had wanted to charge £20 for the camera. Dad won the toss but gave the chap £3 anyway. Honour was restored.

By about lunchtime we were in the Seamen’s Mission and Paddy was a happy man. No wonder, they served chilled Harp! I remember we all ate loads of corned beef sandwiches. There were bullet holes and shrapnel marks all over the walls, it was weird. The soldiers declined an offer of a cold beer each and stayed just outside.

In mid afternoon we walked in the heat back to the pier. It wasn’t as far as I thought so maybe we had taken a circuitous route without realising it. It was time to pay off the guide and Dad took a ten shilling note from his wallet and gave it to him. He scowled but accepted it without a word. Dad and Paddy shook hands with the Corporal and Dad gave him a £5 note.

“Buy the boys a few beers in the NAAFI tonight and thanks for looking after us.”

We all climbed back into the same motor boat and in a short time we were back onboard Bendoran and just pleased to be back home, as it were.

We sailed about six o’clock and I photographed a Russian frigate at anchor out in the bay. It was covered in rust and I remember Dad saying, “S*** navy.”

Twenty four hours later we were out in the Gulf of Socotra and heading for the Indian Ocean. Dad turned on the wireless to listen to the News on the BBC World Service. The opening bars of Lili Bolero filled the airwaves followed by:-

“This is London. The world news read by… …An explosion in the Seamen’s Mission in Aden has killed several people and…”

We all just looked at each other.

Over thirty-four years later I saw on TV the charred hull of the American destroyer USS Cole after it had been attacked by Islamist suicide bombers in Aden. Seventeen good men lost their lives. The Cole had been moored in Steamer Point very close to where we had been on Bendoran. Like I said, Aden is a s***hole!

CONTINUED NEXT MONTH

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item