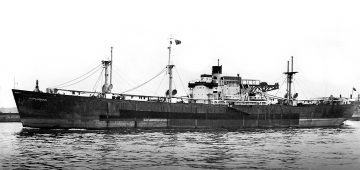

by Capt Sandy Kinghorn

My last voyage in the Columbia Star 1951, still as a cadet, began at Newport, an old Bristol Channel coaling port, now in Wales but then still in Monmouthshire, England. Here we were loading all manner of general cargo from heavy machinery, steel pipes for the Alberta oilfields, furniture, grand pianos, Dainty Dinah toffees, etc. Our next port would be Barry to load, we were told, over 200 aerial bombs. These could blow us all sky high if they went off, we were told they were “lgnltioned” and maybe that was true.

“Are we going to war?” “Not yet, they are a new type of bomb, for the Canadian Royal Air Force”. Very carefully loaded from a wooden barge into a specially constructed wooden magazine in No 2. Tweendeck, my mate Peter and I tallied them in. He made it 251, I made it 247 so we settled for 249 and I went to tell the mate, who was sitting in his cabin with a senior-looking R.A.F. officer.

“Sure there aren’t 250?”

I nodded. The R.A.F. demanded a recount This would have meant unloading and reloading and we had to sail on the evening tide in an hour’s time, but a missing bomb was a serious matter. I thought it might help if I explained how we arrived at that figure. The R.A.F. looked doubtful until the mate poured him an enormous gin, whereupon he cheered up. I was dismissed and we sailed.

In the Bristol Channel we swept through the swan song of Masefield’s Dirty British Coaster with a salt-caked smokestack butting into a rising westerly gale at six or seven knots, woodbine funnel aft, open bridge amidships, two or three stumpy masts, coaly smoke streaking astern as they pitched into the gale. Dozens put to sea on the tide – the high tidal rise and fall in the Bristol Channel has always made ships leave in groups. We passed the three masted schooner Result under sail and power and clean, squat little motor vessels known to seamen as ‘skoots’ (from the Dutch schuyt) carrying coal, steel, and slates, building materials, general cargo, even passengers around the narrow seas. Soon we left them astern and by near sunset the distant sky was a pale wash of lemon beneath a grey stormy rack. Silhouetted on the horizon was a destroyer and a heavily listing ship accompanied by a tug, the Turmoil towing Captain Carlson’s Flying Enterprise which was to sink the next day while trying to reach Falmouth, fortunately without loss of life. Occasionally we came across a French or British weather ship rolling gunwales under and hardly visible in the steep Atlantic swell.

At bunkering port Caracas Bay in Curacao the Dutch authorities took a keen interest in our bombs. An armed soldier was on the gangway while another was on deck patrol. The latter decided to take a look – after I gave him the hatch key. When he emerged his face was a study in chalk. He had missed his step and tumbled from the shelter deck down into the tween deck, landing among the bombs.

We embarked our Panama Canal pilot inside Cristobal breakwater and once through the Canal headed for the Canadian naval port of Esquimalt to deliver our bombs. Fortunately the R.C.A.F. tallyman made the total precisely 250!

Vancouver harbour is one of the world’s beauties, surrounded by forested hills redolent with the scent of pine tinged with woodsmoke. The transcontinental railroad passed near our Ballantyne Pier berth so we were lulled to sleep by the clang of locomotive bells as the huge steam engines rolled past.

Outward cargo discharged, we ‘cleaned and cooled’ ready to load our next cargo – wooden boxes of apples. The holds were first floored with billets of zinc – good bottom cargo – over which the apples were loaded. After Vancouver, Seattle – gateway to the Golden West for more apples. On deck we stowed timber, which Canadians call lumber, then it was up the Columbia River to Portland, Oregon, a memorable run through the countryside past pine-clad cliffs and racing rapids, lush green pastures and towns on the edge of the woods, always with the pilot giving orders in a totally unflappable manner. In those days there were still echo boards, like large hoardings at turns in the river. As a ship approached the bend in fog the pilot would sound the ship’s siren. When the echo was heard it was time to alter course. This of course was before radar made it all easy!

Off San Francisco the pilot swooped upon us in one of the last genuine pilot schooners, the Californian, to take us in though the Golden Gate, past Alcatraz, then still a grim island penitentiary, to berth at one of the many wooden finger piers crammed with shipping beneath the elegant white skyscrapers. A few years later those piers were empty, broken and dilapidated like so many of the world’s older ports. Business has moved across the bay to vast container terminals whose very efficiency has cost the ports their individual charm. After a week in San Francisco we headed up the Sacramento River through a wide flat region not unlike our Norfolk Broads to Stockton California, where we loaded dried fruit in wooden cases.

In port, Peter and I worked alternate days on gangway and cargo watch. The gangway cadet, in his best uniform, answered the telephone, took visitors to the captain and senior officers, ensured that each mooring rope had its ratguard, hoisted flags in the morning and took them down at night. We learned the hard way that the Stars and Stripes particularly had to be treated with great respect. If it accidentally trailed on deck during lowering (these flags were three yarders) the nearest cargo winch driver would leap down from his perch and deliver a stern lecture – usually in thick mid-European accent – on the necessity of preserving the dignitiy. We could do what we liked with our own flag (he even offered suggestions) but not with Old Glory. Quite right too!

Above all, gangway watch entailed keeping the gangway at the correct height. Those magnificent varnished teak gangways with their brassbound self-levelling steps took a lot of looking after, unlike today’s aluminum turntable jobs whose wheels rest on the quay. Those wooden ones had to be lowered as the tide rose, and raised with a small twofold purchase, a handy billy, as the tide fell. The nightwatch sailor tended it by night. Cargo watch was more interesting as we watched all that was loaded and unloaded, noting any damage, keeping times in the book and keeping a plan book to show where each item was stowed. Each day the second mate scrutinised our plan book along with those of the 3rd and 4th mates, entering this information on his master cargo plan. This when finished showed every piece of cargo in the ship and its weight. A well made cargo plan can be read by a stevedore at a glance. From it he orders his labour gangs and advises consignees and transport when to collect. The cargo watch cadet, however junior, must keep aware of all this, alert to any damage caused by dockers to cargo or ship. Safe carriage of the cargo and protection of the ship is the name of the game.

After a wet,wintry passage down the Californian coast we came on the tail of a Santa Anna, a local dust storm, to Los Angeles where we loaded sacks of borax, soft white and silent to walk upon, and bales of cotton, high fire risk.

Then, fully laden, we headed back through the Panama Canal for home. Shortly after bunkering and clearing Cristobal we took our first year examinations set by the Merchant Navy Training Board (after a hard day’s work, of course!) Posted to London by the captain our papers were returned marked within a month or so. A cadet doing badly was told to either pull his socks up or quit.

Clearing Mona Passage out of the Caribbean we struck the most abominable weather ever experienced in nearly fifty years at sea. The gale shrieked from the east causing sea and sky to melt in a welter of foam and spray, a reeling world of grey and white. Even hove to we still took heavy seas aboard: around us unseen vessels transmitted “I AM NOT UNDER COMMAND” signals. Seas crashing over the bow attacked the face of the deck timber stow until eventually heavy planks were loosened, tossed like matchsticks and lost. Sailors and cadets were sent to tighten the lashing chains with bottle screws and marlin spikes, clinging for life as sea after sea crashed aboard in a chill, body battering cascade. Exhilarating work and the closest we ever came to life in a windjammer.

One of our three cabin portholes was stove in by a sea one night, fortunately while we were out baling sea out of the inside cross alleyway. Stilettos of glass showered the soft furnishings, ribboned the curtains, smashed the light and embedded themselves in furniture and wooden bulkheads. The cabin was awash. That sea so strained the bulkhead that for the rest of the trip we moved to spare, dryer accommodation.

Our twelve elderly passengers took the storm in their stride and like us, actually seemed to enjoy it. Fortunately there were no serious injuries. After ten days of such buffeting we were glad to creep quietly into the Clyde, licking our wounds.Those bonny banks and braes never looked more beautiful.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item