There have been numerous collective nouns to describe liners over the years, amongst the most prominent being ’the Cunard Queens’, North German Lloyd’s ‘Schnelldampfers’ and Albert Ballin’s ’Big three’. Nevertheless perhaps none have been quite as evocative as Lloyd Sabaudo‘s ‘Conti’.

Lloyd Sabaudo traced its origins back to June 1906 but despite its royal patronage subsequently endured a turbulent career until the Marquis Renzo Durand De La Penne, in collaboration with his friend Guglielmo Marconi and Sir William Beardmore, owner of the eponymous Scottish shipyard, revitalised the line shortly before World War I. Previously Lloyd Sabaudo had been a small player on the Atlantic but in the immediate post-war era invested significantly in new tonnage. Most conspicuous were a pair of new liners for the Genoa to New York service built at Beardmore‘s Dalmuir facility. Despite their lengthy gestation the Conte Rosso and Conte Verde symbolised the company‘s new found confidence and were briefly the largest Italian passenger ships afloat. Nevertheless Lloyd Sabaudo did not rest on its laurels and just a year after Conte Verde’s delayed introduction, in May 1924, a contract was signed with William Beardmore & Company for a larger consort. The contract also provided an option for a second vessel.

The selection of Beardmore to construct the new ship was controversial. Not only had labour and funding issues plagued and significantly delayed her predecessors but the growing political imperative from Rome was for Italian lines to support the nascent national shipbuilding industry. Nevertheless, overriding these objections the Scottish yard was chosen on the basis of both cost and expertise. Construction was heavily subsidised under the British Trade Facilities Act, a means of protecting vulnerable businesses considered important to the national interest. Additional funds came from the sale of Lloyd Sabaudo’s interest in Marittima Italiana, a line that operated to India and was acquired by Lloyd Triestino. The fact that Sir William Beardmore, by then Baron Invernairn, still sat on the company board may also have been a factor.

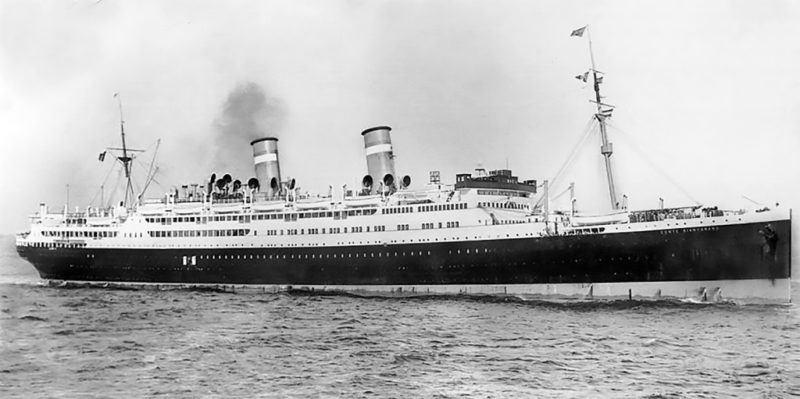

As if to compensate for the delayed delivery of Conte Rosso and Conte Verde, yard number 640 was built in record time. Indeed the first keel plates were laid in June 1924, just a month after the contract was signed and the hull was launched less than a year later, on 23rd April 1925. The new ship was named Conte Biancamano (White Count) by Marquise De la Penne, whose husband had been instrumental in turning the company’s fortunes around. As with her predecessors the name honoured Lloyd Sabaudo’s royal patrons’ heritage, in this case Umberto I, the eleventh century founder of the House of Savoy, whose pale hands were the source of his nickname. Work on the ship was so rapid that she was ready for trials by the start of November.

At 24,416grt, with a length of 198.91 metres (652.6 ft) and a breadth of 23.2 metres (76.1 ft) the new vessel was in effect an enlarged version of the earlier Conti, replicating their sturdy, balanced profile, from the straight stem to the attractive ’classic’ clipper stern. The long black hull and no-nonsense, white superstructure were topped by a pair of evenly spaced, gently raked cylindrical funnels, surrounded by ventilator clusters. As with the earlier vessels Conte Biancamano had a pair of tall raked masts supporting numerous cargo booms and a wood-clad bridge with sheltered ’cabins’ on the tips of each wing.

If she was considered externally handsome it was her interior appointments and décor that really set her apart. As they had with Conte Rosso and Conte Verde the Florentine Coppedè brothers designed the First Class public spaces, indulging their propensity for embellishing historical themes. Accommodation was provided for a grand total of 1,750 passengers in four classes, 280 in First, 420 in Second, 390 in ‘Economy second’ and 660 in Third class. She had nine passenger decks, simply designated Sun Deck, Boat Deck and then Decks A to G. As was common practice at the time, First Class occupied the choice central areas, Second just aft of amidships, Intermediate Second towards the stern and Third Class was placed right forward.

Despite their proportionally low numbers First Class inevitably enjoyed the majority of deck space, outside on Sun and Boat Decks and internally on decks A to E. The most expensive staterooms were located on A deck and included private bathrooms with the luxury of full sized bathtubs. Other cabins were slotted in around public rooms on B, C and D deck and on the port flank of E deck. The impressive public rooms included a cavernous, full width ‘Grand Social Hall’ and the exceptional ballroom. The latter rose up through three floors, featured Arabic arches, huge chandeliers and incorporated a vast Persian rug that was said to have once adorned the Shah’s palace.

By comparison Second and Economy Second were essentially shoe-horned into the stern. Second Class had outdoor promenade space on Sun Deck and some more encircling separate smoking, writing and ladies drawing rooms on A deck. Economy Second had only one lounge (a smoking room with its characteristic semi-circular aft wall) located aft of the dining room on B deck. The Second Class dining room was immediately forward of its Economy Second counterpart.

Third Class was a step up in terms of accommodation and facilities over previous steerage offerings. Cabins were forward on D, E and F decks, mainly four berth with wash hand basins but communal toilet and bathrooms. Outdoor space involved congregating around the forward cargo hatch on B deck but there was also a sheltered promenade area together with the smoking room below on C deck. Completing the Third Class public rooms were the dining room, to starboard on D deck and a drawing room. In addition to the human cargo the new ship offered 162,000 cubic feet of general and 49,000 cubic feet of refrigerated freight space.

After her record completion Conte Biancamano undertook sea trials in the Firth of Clyde over Monday the 2nd and Tuesday 3rd November 1925, reaching 21 knots thanks to her double reduction geared turbines. Four days later she was formally accepted by Lloyd Sabaudo and left Scotland for Italy. She would be the last Italian passenger liner to be built abroad.

With Captain Turchi on the bridge and a healthy complement of 1,503 passengers ensconced below, Conte Biancamano departed Genoa on 20 November 1925, arriving in New York just over 9 days and 7 hours later, having endured a predictably turbulent winter crossing. To the satisfaction of her owners she marginally exceeded the designated contract speed of 20 knots despite the elements.

Following the introduction of Conte Biancamano on the service to North America Lloyd Sabaudo dispatched Conte Verde to the La Plata service. Despite evident satisfaction with their new flagship and contrary to their general wishes the board finally bowed to government pressure in early 1926 and decided not to exercise the option for a second ship from Beardmore’s. Rivals Navigazione Generale Italiana (N.G.I.) had long curried favour by patronising Italian yards but this would be Lloyd Sabaudo’s first such order. Only two yards were considered to have the requisite expertise and infrastructure for such a large liner, Ansaldo at Genoa and Cosulich’s Monfalcone facility. Since both had full order books Lloyd Sabaudo had little option but to engage Stabilimento Tecnico at San Marco. Although a longstanding builder of naval and cargo vessels the Trieste yard was unused to large passenger ship construction and so it wisely decided to utilise Beardmore’s Conte Biancamano blueprints as a template, much to the chagrin of the Dalmuir workforce.

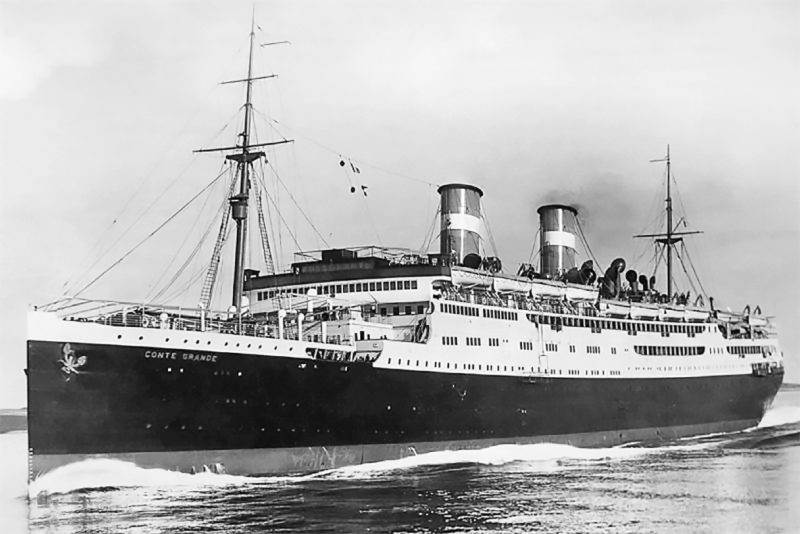

On 24th October 1926 the keel was laid of the last of the Lloyd Sabaudo Conte quartet. Just over eight months later, on 29th June 1927, she was named Conte Grande by the Duchess d’Aosta and slid into the Adriatic to the cheers of the large assembled crowd. Bestowed in recognition of his wisdom and leadership, the name again related to an early ruler of the House of Savoy, in this case Amadeus V who ruled from 1285 to 1323. Externally the Conte Grande was almost identical to her Scottish built sister. The main distinctions were the new ship’s rather ungainly extended forward superstructure (housing the First Class reading room), and alternative arrangement of lifeboats. Internally she made even Conte Biancamano’s lavish interiors look positively pedestrian. In a final fling of rococo indulgence, the Coppedè brothers, in tandem with the Roman designer Brasini, incorporated an eclectic mix of eras and styles ranging from Elizabethan England in the writing room to the Old Dutch smoking room and an Indian-Oriental veranda café. In some ways this ‘fantasy’ style would be replicated by Joe Farcus’ Carnival cruise ship interiors in the later part of the 20th Century and it proved equally popular with American travellers. If to some it appeared over the top and a little ridiculous, for the majority it simply represented an idealised view of ‘Olde Europe‘.

Utilising the same power plant as the ‘White Count‘, Conte Grande achieved a very respectable 21.83 knots on sea trials before being accepted by Lloyd Sabaudo on 19th February 1928. Early the following month Conte Biancamano undertook an exceptional, record breaking voyage to Buenos Aires. By 24th April she had reverted to her normal North Atlantic service, joining her new near sister which had sailed on her maiden voyage from Genoa on 3rd April 1928. The advent of Conte Grande resulted in a comprehensive restructuring of the Lloyd Sabaudo fleet, with Conte Rosso joining her sister on the South America service and a variety of older tonnage being laid up and scrapped. It also coincided with increased government intervention. The previous year there were reports that Mussolini wanted to amalgamate the three principal shipping lines (N.G.I, Lloyd Sabaudo and Cosulich) under a single, state subsidised, conglomerate. Although vocal opponents of such an idea, Lloyd Sabaudo did concede to an arrangement, starting on 1st July 1928, in which the companies pooled resources and aligned fares and schedules. It wasn’t only politically pragmatic, the agreement also brought increased subsidies and ended unprofitable competition between the lines.

Despite acceding to these demands Lloyd Sabaudo still maintained a degree of autonomy and in September 1928 introduced a new air/sea service in which flying boats met Conte Grande and Conte Biancamano at Gibraltar, airlifting and thereby expediting the delivery of the mail and later V.I.P.’s. The company also stood out for its publicity material, with posters and lavish brochures depicting the ships and their namesakes. The two Conti were now sailing in tandem with contemporaries Roma, Augustus (N.G.I.) Saturnia and Vulcania (Cosulich) but whilst the Trieste based company was content to stick with its niche market, the Genoa based rivals were casting envious eyes at their North European competitors. N.G.I. and Lloyd Sabaudo’s ambition was matched by the government who offered generous building and operating subsidies allowing each line to commission a 45,000grt liner. Initial proposals suggested that Lloyd Sabaudo’s new ship would be a larger, three funnelled version of Conte Grande but these plans were later scrapped, to be replaced by a very modern vessel. Inadvertently, in seeking to fulfil their ambition Lloyd Sabaudo were encouraging their own demise.

The ramifications of the US stock market crash were felt in every facet of business and shipping was not immune. As a short term measure and with transatlantic traffic in decline Lloyd Sabaudo were not alone in sending Conte Grande on a West Indies cruise over the winter of 1929/30. Nevertheless with shipping companies struggling to survive across Europe, state intervention became the norm rather than the exception. It was therefore hardly surprising, when at Il Duce’s insistence, communications minister Count Ciano convened a meeting of N.G.I., Lloyd Sabaudo and Cosulich leaders in October 1931 with a proposal they couldn’t reasonably refuse. The ’document of co-ordination’ was signed on 11th November and Italia Flotte Riunite, the Italian Line, came into being with effect from 2nd January 1932.

Six days after it was formed, sporting her smart new red, white and green funnel livery but otherwise unchanged, Conte Biancamano inaugurated Italia’s service from Genoa to New York. Conte Grande followed a fortnight later. The ‘White Count’ was in the wars on her subsequent New York sailing, battered by heavy seas that necessitated impromptu repairs at a Brooklyn yard before sailing a day late, on 24th February 1932, on the Italian Line’s first Mediterranean cruise. The Eastern Mediterranean itinerary would become an company staple in later years, cementing the reputation of ships like Leonardo da Vinci but for now it offered an exotic distraction from the ongoing economic depression. Conte Biancamano called at Gibraltar, Naples, Athens, Rhodes, Haifa, Alexandria and Naples.

A restructuring of the company fleet with the arrival of Rex and Conte di Savoia would soon see the sisters split and the last vestiges of Lloyd Sabaudo’s original ’Conti’ quartet disappear forever. Conte Rosso had been chartered by Lloyd Triestino at the time of the amalgamation but six short months later, at the end of May, Conte Verde joined her on the Far East route. On 8 September Conte Biancamano steamed out of Genoa on her second voyage to South America. This time however it wasn’t a one off but part of the company’s fortnightly Buenos Aires service calling at Villefranche, Barcelona, Dakar, Las Palmas, Rio de Janiero, Santos and Montevideo on route. Meanwhile supplementing the two new flagships’ fortnightly New York express service would be Conte Grande and the similar vintage and sized Augustus, on a subsidiary three to four week cycle. Ironically having been usurped as prima donna Conte Grande played a very significant role in saving the new Rex’s blushes in October 1932, when she arrived in the Big Apple from Genoa on the 10th with a team of Ansaldo shipyard engineers and mechanics. They were tasked with rectifying the generator and plumbing issues that had incapacitated and delayed the national flagship’s maiden crossing.

The parlous state of regular liner services encouraged the Italian Line to send a number of ships cruising during the winter/spring ’low’ season of early 1933. Conte Grande was particularly prominent in this role, starting with a 32 day odyssey to the Eastern Med from New York on 6th January, followed by repeated Caribbean itineraries through until mid-May. When she finally returned (temporarily as it transpired) to North Atlantic crossings she had been refitted, with Second Class accommodation upgraded to meet the demands of the new Tourist Class clientele. There had never been a commercial justification for building the super liners and the route was clearly over-tonnaged so there was little surprise when first Conte Grande and then Augustus were transferred to the South American route. On 28th September the former Lloyd Sabaudo flagship steamed out of Genoa on her first crossing, arriving in Buenos Aires on 13th October.

The sister’s reunion was brief, in fact lasting less than a year. Conte Grande and Augustus may have replaced Giulio Cesare and Duilio, which started a South African service early in 1934 but they also left Conte Biancamano redundant. Following her return from South America on 24th May 1934 and a week-long Med cruise she was laid-up at Genoa with a brief spell at Bari in September. She was joined by others, forming a moribund fleet that was ready and waiting for Mussolini’s controversial colonial exploits in the Abyssinian Campaign the following year. Conte Biancamano would make twelve voyages to Massawa (Italian Eritrea) and Mogadiscio (Italian Somaliland) between February and September 1935 as Italian forces and supplies were built up in advance of the October invasion. The first sailing on 24th February with 2,600 men of the Peloritana Division attracted what maritime author Peter C. Kohler describes in his magnificent book ‘The Lido Fleet’ as a wave of “patriotic fervour with huge cheering crowds seeing off modern-day Roman legions and the ships plastered with portraits of Mussolini.” The ships were unaltered for the task with class divisions used to segregate the troops into officers (First Class), NCO’s (Tourist) and ordinary soldiers (Third) with hammocks strung up where appropriate. After such a patriotic send-off the soldiers doubtless felt a little different when they arrived in the searing heat and lonely, insect riddled anchorage at Mogadiscio.

Whilst Conte Biancamano was on her trooping assignment Conte Grande was undertaking new duties, having been drafted in as a temporary replacement for Saturnia and Vulcania (also chartered for trooping) on the Adriatic service from mid-May. With the exception of a thirty five night cruise from New York to the Eastern Mediterranean commencing on 3rd July she remained on the service until the end of September, commencing her fourth and last fifteen day crossing from New York on 14th September, calling at Boston, the Azores, Lisbon, Gibraltar, Algiers, Naples, Palermo and Patras on her way to Trieste. By then, despite (somewhat hypocritical?) British and French admonishment at Italian colonial ambitions and the imposition of sanctions by the League of Nations, the invasion was logistically and politically inevitable, leading to reduced passenger loads as Americans were advised against travel on Italian ships. Conte Grande’s return to the South America run was equally short-lived when in a surprise move she was replaced by the de-mobbed Conte Biancamano from the beginning of January 1936. Conte Grande was summarily laid up.

Despite overwhelming technical and equipment superiority, victory in Abyssinia took seven brutal, hard-fought months but after its conclusion the Fascist Government turned its attention to reforming key sectors of the Italian economy. Direct state involvement and ownership becoming increasingly prominent. Shipping was considered one such important industry with the government proposing the creation of four new state owned lines, based on geographical segmentation under the umbrella of Società Finanziaria Marittima (FINMARE) based in Rome. Although the various parties reached agreement by the end of May 1936 it would take until December to finally have the relevant legislation pass through Parliament. In the ensuing redistribution of tonnage Conte Biancamano was reassigned to Lloyd Triestino, (which would be responsible for services to India, Africa, Asia and Australasia) making her final Italian Line voyage from Buenos Aires back to Genoa on 23rd February 1937. Replacing her sister on the La Plata service after a year of inactivity was Conte Grande, part of an Italian Line fleet which would thereafter concentrate on its core North, Central and South American itineraries.

Having long been overshadowed by her sister, larger former N.G.I. fleet mates and the new super liners, as well enduring extensive periods of lay-up, it was good to see Conte Biancamano once again take the spotlight as flagship of Lloyd Triestino. On 12th March she entered the OARN dry-dock for a thorough refit in preparation for her new role. Externally she well suited the buff yellow funnels and tropical white hull with smart blue sheer band and had a full Lido and swimming pool installed between her stacks. Internally she was thoroughly refurbished and improved to meet the demands of her new express luxury service from Genoa to Shanghai. Operating in tandem with the exquisite Victoria and former Lloyd Sabaudo fleet mates Conte Rosso and Conte Verde Conte Biancamano became an immediate success when she embarked on her maiden voyage to the Far East on 16th April 1937.

For the next two years the Conti continued to serve their respective routes with distinction but despite the false hope of Mussolini’s brokered Munich agreement in September 1938, war became more and more of an inevitability as 1939 progressed. In fact both ships were involved in an often neglected humanitarian exercise through much of that last year of peace. On 28th January 1939 the China Mail reported the arrival in Hong Kong of over 1,000 Jews (mainly German escaping persecution) on Conte Biancamano to start a new life in China. At the same time Conte Grande’s passenger complement included Jewish evacuees bound for a new life in South America.

On 22nd August the announcement of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact effectively removed the final check on Hitler’s expansionist ambition. Conte Grande arrived in Buenos Aires on 26th August and was preparing to sail for Europe on the 29th when the Argentine authorities detained her. Meanwhile Conte Biancamano was steaming east. She failed to arrive in Bombay, as scheduled on the 29th but was reported in Hong Kong on 10th September via a circular route and with another final batch of Jewish refugees, six days after Italy’s surprise declaration that it was to remain neutral in the ensuing conflict. On 8th September Conte Grande was released and sailed home from Buenos Aires. With Italian flags prominently emblazoned on their flanks the Conti and their fleet mates continued to ply their schedules throughout the autumn and winter of 1939, despite the submarine threat and increasing inspections by British and French officials at interim ports of call.

The New Year started inauspiciously for the Italian merchant fleet when an engine room fire engulfed Italia’s Orazio, soon after departing Toulon on 21st January 1940. Conte Biancamano was one of several ships to respond to the SOS call and pick up survivors but over 100 passengers and crew lost their lives. Having returned from Shanghai in February the ‘White Count’ was promptly chartered by the Italian Line as a replacement, departing Genoa on 23rd April, once more sporting red, white and green funnels, bound for the Pacific coast of South America. By April the British blockade of Gibraltar and related inspections were becoming even more thorough. As all pretensions of the phony war evaporated in May and June of 1940, Mussolini injudiciously entered the fray on the Axis side, believing the allies would capitulate and anticipating an easy ‘land grab‘ in France and North Africa.

Unlike in September the previous year, Il Duce’s hurried mobilisation and declaration of war against Britain and France on 10th June did not allow sufficient warning for all its merchant fleet to find home waters or a neutral port. Although advised of the impending decision two days earlier, it provided hopelessly inadequate time for the Conti to find refuge. Indeed they were the largest units in the Italian fleet to be marooned, in Santos (Conte Grande) and Balboa (Conte Biancamano) respectively.

Conte Grande had arrived in Santos on the 9th June and was ordered to remain in port. Her incarceration would last over a year. Meanwhile Conte Biancamano languished in and around the Panama Canal, subject to a US Marshall’s law suit and rumoured to be making a run for home. To have tried would have been pure folly, even if she had evaded the encircling British blockade of the Canal Zone she could never have made it through the Straits of Gibraltar. Instead she lay alongside at Cristobal whilst the remnants of her passengers and cargo were off-loaded.

After almost nine months of ennui the arrival of a U.S. Coast Guard deposition on 21st March 1941 signalled a change for Conte Biancamano. The authorities identified systematic sabotage of the ships’ main and auxiliary machinery, bolts and ironwork were poured into the turbines which were then set in motion, shattering blades in clear violation of American neutrality law. Having arrested the Captain, Chief Engineer and other members of the engine room staff, remaining crew members were lead ashore and transferred to an internment camp on the mainland. Five months later, on 30th August she was taken in tow and moved to the Panama Canal Company yard at Balboa. Here auxiliary machinery was mended whilst the main turbines were sent to the USA for repair and reconditioning. That same month, on 22nd August 1941 Conte Grande was seized by the Brazilian Government.

With repairs underway Conte Biancamano was formally seized by the U.S. government on 7th November 1941 with the intention of leasing her to United States Lines for a proposed troop, passenger and freight service from New York to an unspecified UK port via Canada and Iceland. The Iceland call was particularly pertinent, relating to Roosevelt’s agreement with Churchill in June 1941 whereby U.S. forces would replace the British garrison on the island. Lost in the events of 8th December 1941, when the United States declared war in response to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour the previous day, Conte Grande was rather perversely opened as a hotel, managed by Lloyd Brasileiro in situ at her Santos berth.

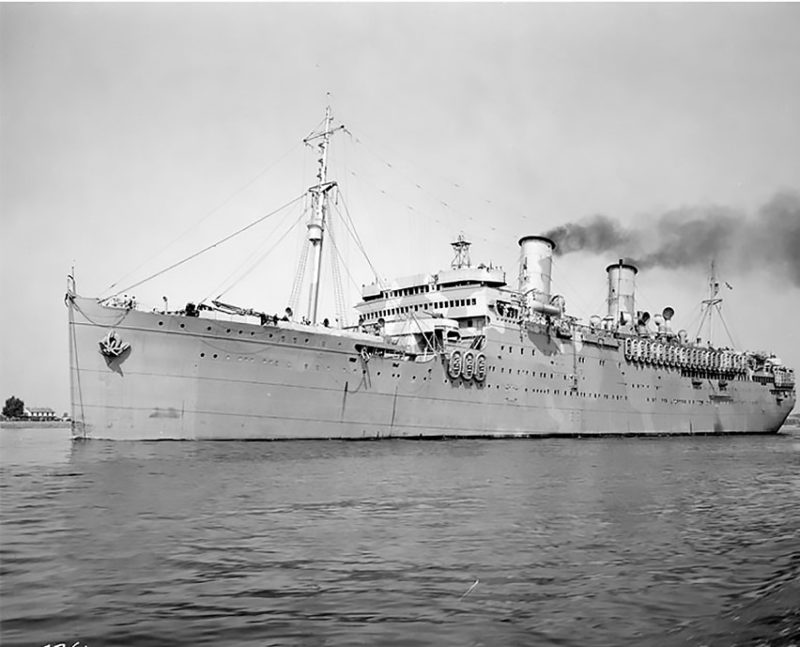

With both governments direct intervention the Italian Line sought and signed (on 22nd January 1942) an agreement with Lloyd Brasileiro in which Conte Grande was chartered for South America coastal service and under which they retained a stake in their former liner’s operation and profitability. Two short months later however, on 10th March, the contract was effectively ignored as Conte Grande was sub-chartered by the Brazilians to the United States. On 16th April she was renamed U.S.S. Monticello and commissioned into the US Navy at Santos, under the pennant number AP-61. Conversion work for trooping duties was assigned to the Philadelphia Navy yard where she arrived on 16th May. Her near sister was also in the Pennsylvania port, having arrived at the beginning of April following the completion of repairs at Balboa. Conte Biancamano was formally commissioned on 14th August, renamed U.S.S. Hermitage and assigned pennant number AP-54.

In order to meet the US Navy’s exacting specifications, significant structural work was required. Coppedè’s grandeur was stripped out of both ships to be replaced by standee bunks and mess facilities for a maximum of around 7,000 troops. Conditions were cramped, hot and unpleasant but this was war and all semblance of comfort would have to wait. Lifeboats and davits were removed and replaced by rows of life rafts, whilst a lattice tripod mast carried early RADAR equipment. Hermitage’s funnels were also reduced in height to reduce perceived top-hammer.

Having completed her conversion in early September U.S.S. Monticello steamed out of New York on 2nd November 1942 with a shipload of GIs bound for the allied invasion of North Africa. The following month U.S.S. Hermitage sailed from the same port on a meandering voyage via Panama and Brisbane to Suez, the South Pacific and Honolulu, before making US landfall again at San Francisco on 2nd March 1943. Both ships became instrumental to the Allied cause throughout 1943, Monticello primarily supplying reinforcements to Oran, Algeria as part of preparations for the invasion of Sicily, whilst Hermitage concentrated on the Pacific theatre. From Melbourne to Karachi, Boston to Wellington, the ships encircled the globe.

In 1944 their deployment became more structured. During the first half of the year both ships were in the Pacific, carrying troops from San Francisco to bolster Allied forces edging east towards Japan. From June onwards they moved to the North Atlantic, ferrying reinforcements to Liverpool, Belfast, Southampton, Plymouth and ultimately direct to Cherbourg for the drive west from Normandy towards the Rhine. On 13th November Monticello departed Newport News on a poignant first return to Italy in over four years, arriving in Naples after a brief call at Gibraltar. The final year of the war started with Hermitage and Monticello making more direct sailings from New York to Southampton and Le Havre. With the German surrender in May came a role reversal, on 3rd June 1945 Monticello received a tumultuous welcome in New York carrying the first instalment of US soldiers and wounded to be repatriated from Europe. They shuttled back and forth, Monticello once more achieving a milestone when she tied up at Pier 84 on 20th July with a record 7,037 members of the 2nd Infantry Division.

Following VJ-Day the near sisters were able to cross with impunity and had their weapons removed at the Todd Shipyards in Brooklyn. They continued on the Atlantic until December when Hermitage sailed on 12th December for Japan, via the Panama Canal and Hawaii. She would continue repatriation duties from the Pacific theatre through until August 1946, when she was decommissioned and sent to join the reserve fleet at Suisun Bay, near San Francisco. Monticello had already been anchored in the James River since May, having returned to New York from Marseille on her last trooping voyage at the turn of the year.

Despite its ‘guilty’ part in the conflict, the United States was well aware of Italy’s strategic importance as a buttress against communist expansion. Accordingly under the auspices of the ‘Treaty of Paris’ signed on 10th February 1947 and as part of a broad range of measures, all former Italian ships under American control were earmarked to be returned to their original owners. On 29th March 1947 Monticello was renamed Conte Grande and handed back to the Italians, departing Newport News in early July for Genoa where her transformation had been awarded to the local O.A.R.N. yard. Meanwhile Hermitage underwent a brief inspection and refit by Bethlehem Steel, in their San Francisco floating dock facility, before sailing for Newport News. On 18th August with an Italian crew on board she made for Messina, having also reverted to her former name.

The Counts were in a desperate condition having been worked necessarily hard by their American task masters. There was some debate as to whether the resources required for their refurbishment might be better spent on new builds. Time however became the overriding factor, with emigration and repatriation a priority it was determined that the Conti could be back in service within two years, whilst new vessels would take at least a year longer. In March 1948 O.A.R.N. started work on Conte Grande and C.R.D.A.’s Monfalcone yard on Conte Biancamano.

After successful trials, dressed overall and accorded a happily rousing send off, Conte Grande sailed from Genoa on 16th July 1949 with an official Italian delegation bound for Buenos Aires. Externally she now sported a modern raked bow, new broader funnels and the company’s tropical white livery, with green sheer stripe and boot topping. More than ever before she suited her famous name. Despite initially being assigned back to Lloyd Triestino Conte Biancamano was delivered on 26th October and joined her near sister on the Italian Line’s La Plata service, with a first departure on 10th November. The ships would run a new monthly service from Genoa calling at Naples, Cannes, Barcelona, Lisbon, Rio de Janeiro, Santos and Montevideo before arriving at their southern terminus of Buenos Aires. Also sporting a modern raked bow (several variations of which had been considered) the ‘White Count’ wasn’t quite as good looking due to retention of her original truncated funnels.

An invitation only competition was held to decide on the appointment of interior designers for the ‘new’ vessels which proved so successful it was adopted for future Italia new builds.

In addition to pre-war architects there was an emergence of young blood. The Conti became prototypes for a completely new Italian ocean liner style, one for which they and subsequent vessels earned a great deal of praise. The clean, simple lines and innovative fabrics and materials were in stark contrast to the lavishly ornate incarnations which the Americans had stripped away in 1942. Contemporary art abounded with each ship a veritable floating gallery.

A ’unitary’ style was adopted for Conte Grande, one in which single architects were given responsibility for the entire vessel, or at least all rooms within a given class. Giò Ponti and Nino Zoncada designed First Class spaces, Matteo Longoni Second and Zoncada Third. In contrast Conte Biancamano followed the ’pluralist’ trend with a host of different designers having responsibility for individual rooms. Gustavo Pulitzer Finali was prominent and Zoncada again featured but there were also roles for an eclectic mix of Trieste based architects, Nordio, Cervi, Frandoli and Romano Boica. Art work by Massimo Campigli, Emanuele Luzzati, Edina Altara, Luca Crippa and the prolific sculptor Marcello Mascherini enhanced the distinctive, clean cut feeling on board.

With the exception of a short stint, between August and October 1956, as a temporary replacement for the ill-fated Andrea Doria on the New York run, Conte Grande remained on the La Plata service for the rest of her post-war Italian Line career. Conte Biancamano’s employment was much more diverse as she effectively became the company‘s utility vessel. Beginning with a 7th March 1950 departure from Genoa, via Naples and Gibraltar the ’White Count’ introduced a seasonal service to New York, with occasional calls at Halifax. In subsequent years she would make up to eight round-trip North Atlantic voyages then revert to her South America schedules over the ’winter’ period. When, prompted by a booming economy, European migration to Venezuela increased in the mid-1950s and a corresponding movement from the West Indies to Europe took hold, Conte Biancamano was selected for several Genoa, Cannes, Naples, Barcelona, Lisbon, Funchal, Tenerife, La Guaira, Curaçao, Cartegena voyages, returning via Port of Spain in 1954,1955 and 1956. Although highly successful in the role, demand on the North Atlantic meant a return to her Genoa-New York supplementary service from June 1956.

In 1957 and 1958 Conte Biancamano reverted to the La Plata route full-time with Conte Grande but in 1959 instigated a new Naples to New York itinerary. The Conti were in their dotage, adored but long since due for replacement when in March 1960 Conte Biancamano’s aging turbines finally showed signs of exhaustion. She arrived at Naples from New York on 21st April and was laid-up prior to disposal. On 2nd August 1960, almost thirty five years after that maiden Lloyd Sabaudo crossing Conte Biancamano was sold to Società Terrestre Marittima and arrived a fortnight later to be scrapped at La Spezia.

Having become a fixture on the South America service for more than a decade Conte Grande was afforded a heartfelt adieu when she departed Buenos Aries for the last time on 25th September 1961 and arrived back in Naples on 15th October. After a period of idleness she made one final commercial voyage, departing in mid-December under charter to Lloyd Triestino with 1,600, mainly emigrant passengers bound for Sydney. On 16th February 1961 Conte Grande arrived back in Genoa after a voyage via Bombay, Aden, Port Said, Messina and Naples. Six months of purgatory came to an end in the late summer of 1961 when she finally steamed out of Genoa for La Spezia where she arrived on 7th September. Scrapping began almost immediately, adjacent to what appeared to be the final remnants of Conte Biancamano.

Despite appearances not every element of the famous Conti had been scrapped. In an unprecedented move the whole forward superstructure of Conte Biancamano was removed and reinstalled, wholesale, in the Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci in Milan. Also taken and lovingly restored was the First Class ballroom and some cabins.

They stand today as the key exhibits in the museum’s vast naval collection, a worthy monument to two of Italy’s most cherished ocean liners.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item