Like many industrial areas, Tyneside must have been an awful place to live in, with so much industry and pollution at the turn of the 19th century. Coal mining, engineering, steel mills, glass, ropes, leather, chemical, lead, pottery factories, salt pans, fish quays, gas works plus numerous other activities. All adding to the unhealthy surroundings, but as the old saying goes ”where there’s muck…”

Tyneside’s wealth had been made from the readily accessible deposits of coal. Conditions endured by generations of miners before mechanisation can only be imagined these days.

The river water was devoid of life, being a dumping ground for coal mining pit slurry, industrial waste etc. it was basically an open sewer. With the population, in the main packed into rows and rows of terraced houses, with insanitary conditions and putrid air quality, public health was poor and infant mortality high.

Employment was never guaranteed, and when the vagaries of trade or stock markets took hold, poverty would not be uncommon.

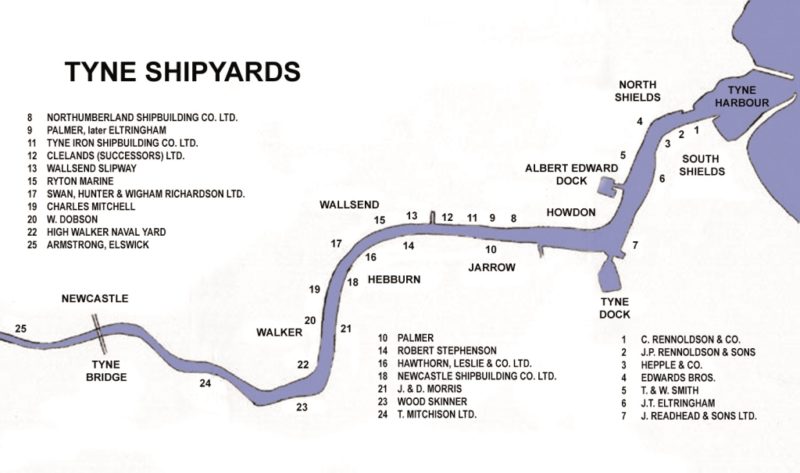

The area had been transformed by the coming of the industrial revolution, led by enlightened engineers of the era. Stephenson (railways), Armstrong (Armaments and shipbuilding), Parsons (Generators and Turbines), Palmer, Whitworth and Hunter (shipbuilding), Reyrolle (electrical switchgear). For the fourteen miles of river from the bar to a few miles past Newcastle was crammed packed with industry, with no vegetation within a mile on either side of the river banks. Against this backdrop the area’s reputation thrived and grew.

Since 1613 the Newcastle’s city Fathers and Freemen had exacted all dues from trade on the river. Even when sailing ships unloaded their solid ballast onto river banks, prior to loading coal, a tax was imposed. The river was shallow with numerous sand bars and islands, which hindered trade up until the mid 1800s. They were slow to adapt and only changed when the loss of trade threatened their livelihoods. Several factors about mid-century changed the whole landscape.

Firstly the coal mine owners of south Yorkshire found they could supply London with coal via the new railway network faster than the sailing ships trading up and down the East coast.

Secondly Charles Palmer’s company had designed a water ballasted steam driven collier John Bowes (above), which would be the game changer.

Thirdly the Tyne Improvement Commission was created to dramatically improve the facilities, and employed an inspired Chief Engineer John Francis Ure.

The Council begrudged the dominance of river trade and river dues etc. to the Commissioners. Up to 1870 they had exacted dues from all coal shipments from the river. In 1901, 458 ships were registered on the river (445,736 net tons) under 141 owners., the largest of which was James Knott’s Prince Line with 41 ships. The majority of the owners were tramp owners or small scale collier operators.

A selection of the shipbuilding scene of 1901 shows that it was going through one of it’s periodical slack times with only 441 merchant ships on the stocks throughout the UK, totalling only 1,300,179 tons. There were almost 80 building berths on the river from trawler size up to 500 feet. Consequently the Company directors of yards were constantly looking of ways of expanding their business. Dr. G.B. Hunter of C. S. Swan Hunter Co. was in Canada looking for more orders for Great Lakes ‘canallers’, and was also looking at starting a shipyard in Halifax, N.S.

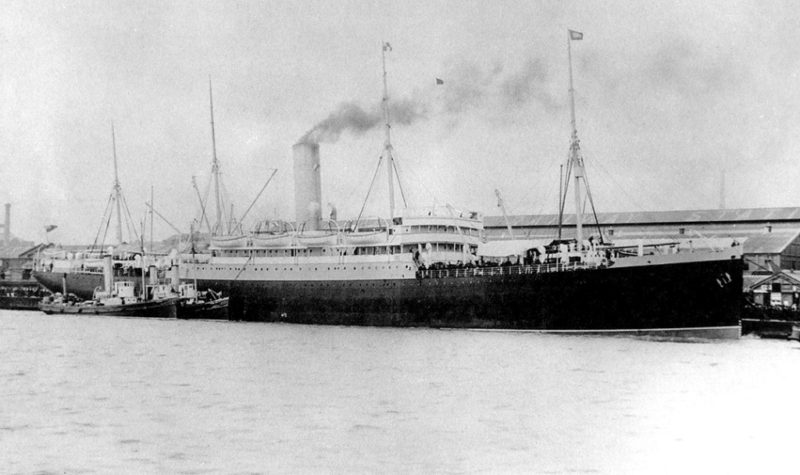

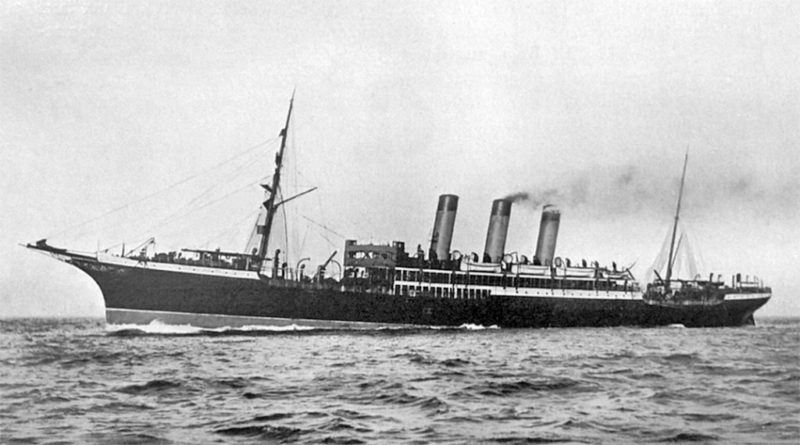

Meanwhile back on the yard, the largest merchant ship built on the river that year the emigrant carrier, Lake Manitoba (above), 9,510grt, for Elder Dempster was completing, with 2 more on order for the same owners. The world’s largest pontoon dock (AFD 1) was in the process of being built at Wallsend, with a lifting capacity of 17,500 tons, for The Admiralty, for use at Bermuda. She was subsequently sold and eventually broken up in Brazil in 1989.

Wigham Richardson at Low Walker were busy with orders for the Baro Fejervary (above) a 3,889 grt freighter Royal Hungarian “Adria” S. N. Co., of Fiume, as well as 4 others for another regular customer D.G. Hansa, who the yard had a long standing business relationship with on cost and reliability.

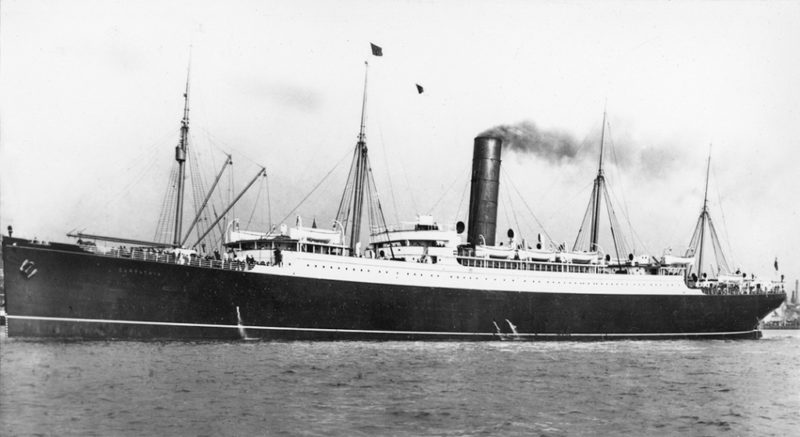

On 18th January 1901 an order for 13,555 grt Cunard emigrant liner was confirmed. They had taken over the order over from New Zealand S.N. Co. Ltd. Several points of interest concerned this, because when the builders were excavating and extending the berth to accommodate the 500 foot long ship they found the eastern extremities of a Roman Wall. Launched on 6th August 1902, the ship was named Carpathia (above), the ship which would be in the public eye 11 years later during the Titanic saga. Also in 1901 the company received a preliminary invitation to tender for another ship for them which in due course became Mauretania.

At Armstrong Whitworth Co. Ltd., Elswick, although they were completing several ships, there was a lack of new warship orders, with the suggestion that the Government might buy the establishment. They only had one tanker on the berths for H.E. Moss Co., which had been transferred from their Low Walker yard. Elswick a suburb of Newcastle, where Charles Armstrong had opened his munitions works and later a shipyard had an increase in population of 3,500 in 1851 to 52,000 by 1891. The population along both banks of the river expanded for the 14 miles to the sea in similar fashion.

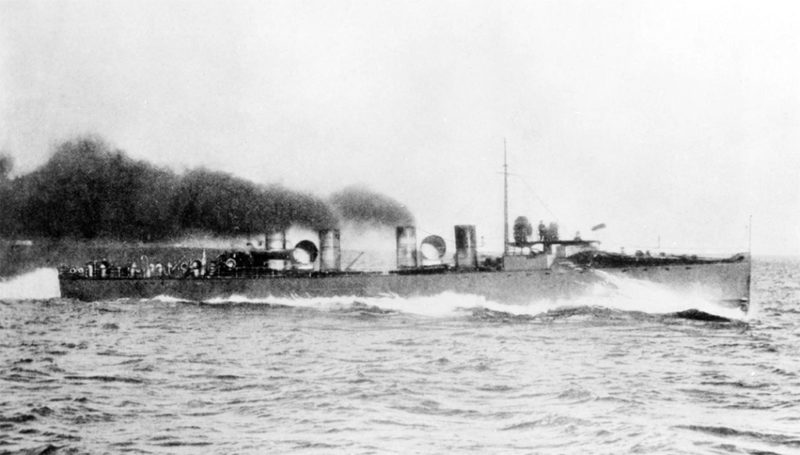

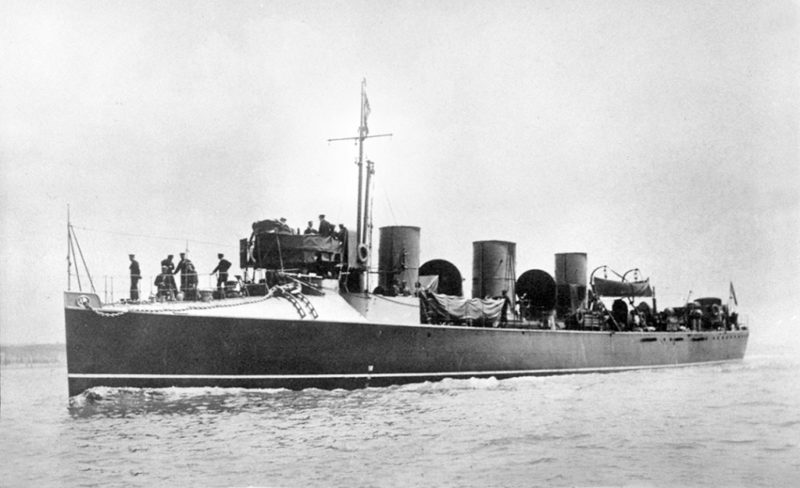

H.M.S. Cobra (above) was launched at Elswick on 28th June 1899. Armstrongs had decided following the success of Turbinia to build a torpedo boat destroyer ‘on spec’, fitted with Parsons turbines. This was sold to The Admiralty in May 1900 and on trials achieved 34.89 knots. The Admiralty were not entirely happy with the ship’s design and the increased displacement of the ship due to the heavy turbines. Modifications were made and the ship sailed from the river on 19th September 1901 for Portsmouth, running into bad weather at a slow speed, and off the East coast, witnessed from a Light Vessel the passing ship appeared to blow up. Fishing vessels on the scene picked up bodies. In total 67 lost their lives. The inquiry found that the structural integrity was to blame, which led to a terrible stain on the company’s reputation.

The Japanese Government, had been a regular customer with yard and during 1901 Hatsuse (above) a 14,312 ton displacement battleship was completed in January, armed with 12 inch guns. She was mined and sunk, at Port Arthur in 1904, during the Russo-Japanese war.

Later in that year the 9,773 ton cruiser Iwate (above) was completed. She would last until July 1945 when bombed and sunk at Kure. Two coastal defence ships built for Norway were also completed in that year. Both were sunk during the German invasion at Narvik in the spring of 1940.

Low Walker (formerly the Charles Mitchell shipyard) were lucky having a full order book, building mainly merchant ships, although they did build the hulls of some warships,which were then towed up river to the Elswick yard for fitting out and completion.

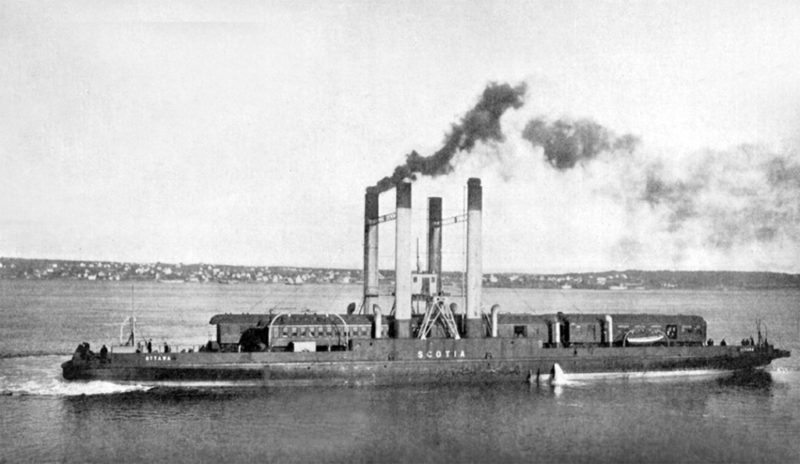

The train ferry Scotia (above), a strange looking ship, for the carriage of railway trains across the Strait of Conso, Nova Scotia, was completed in the year. She was basically a barge, with loading at either end with four enormous funnels

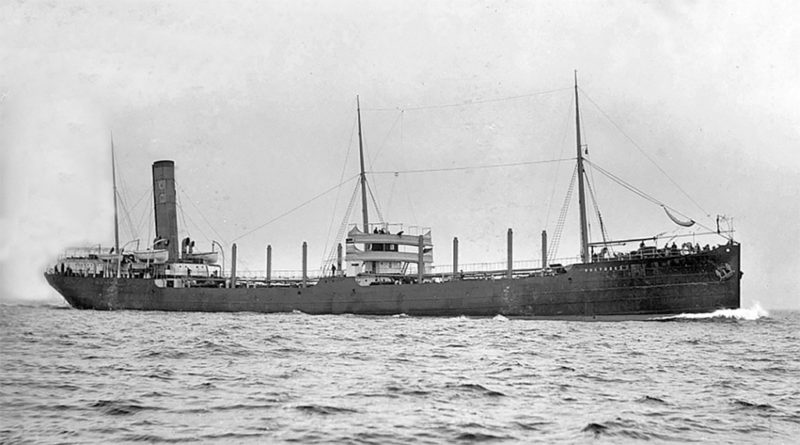

In January 1901 the Shell Transport & Trading Co. tanker Bulysses (above) was lying at the fitting out quay. She had been completed in August 1900. On sailing from the river on her delivery voyage to Alexandria, with shipyard staff onboard, she collided with and sank the inward bound collier Greenwood off the mouth of the river in thick fog, and sustained considerable structural damage. The Court of Appeal blamed the tanker’s captain for failure to take evasive action. She would become another casualty of World War I, when torpedoed and sunk on 24th August 1917.

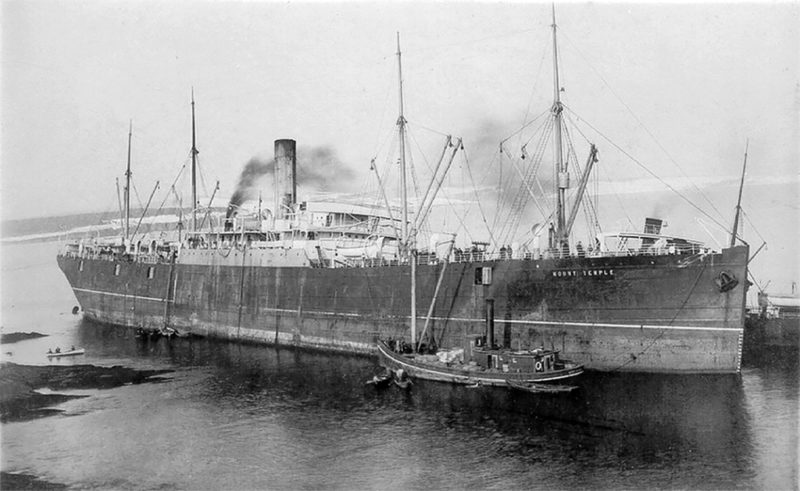

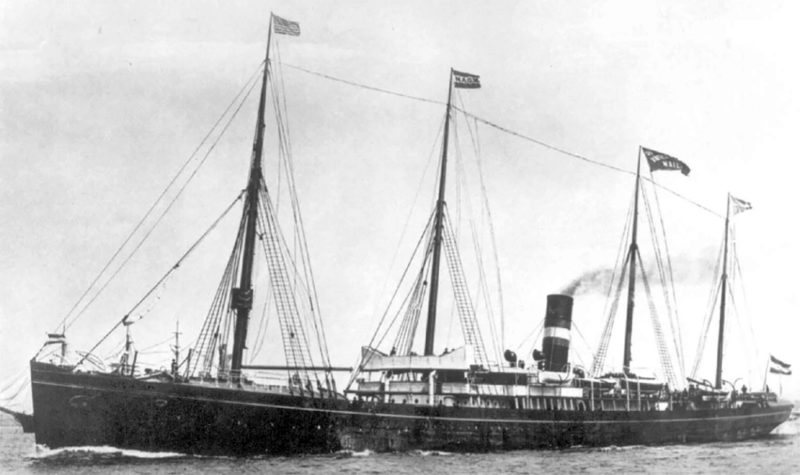

Mount Temple (above), 8,790 grt, another ship of Elder Dempster’s Beaver Line emigrant liners, was building, which in 1912 controversially did not respond to Titanic’s SOS.

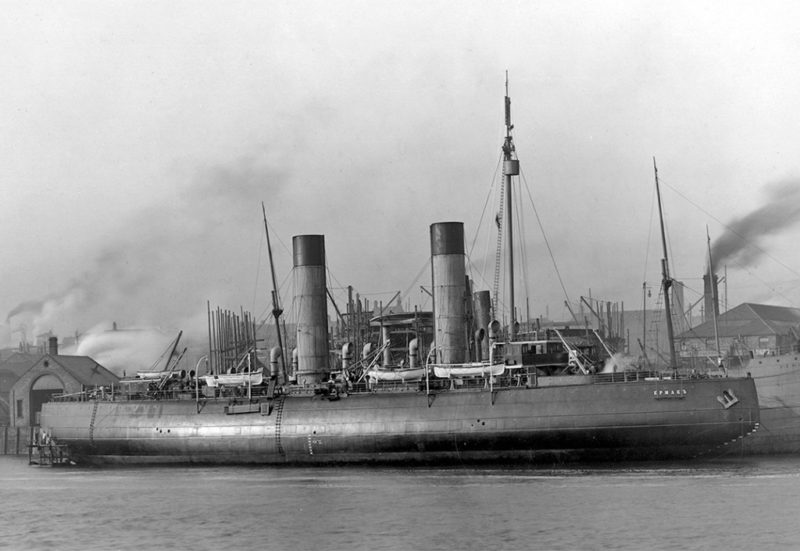

The shipyard had a long standing relationship with the Imperial Russian Government, and had built many ships including ice breakers for them. One of these the Ermak (above) of 5,128 grt which had been launched from the yard in October 1898. For use in the Baltic, she also went into Arctic waters, coping with ice 20 foot thick with ease. However in 1901,when faced with 80 foot thick ice, it proved too much and she damaged her bows. The ship returned to her builders, dry docked on the river and returned to service. She was finally broken up in 1965.

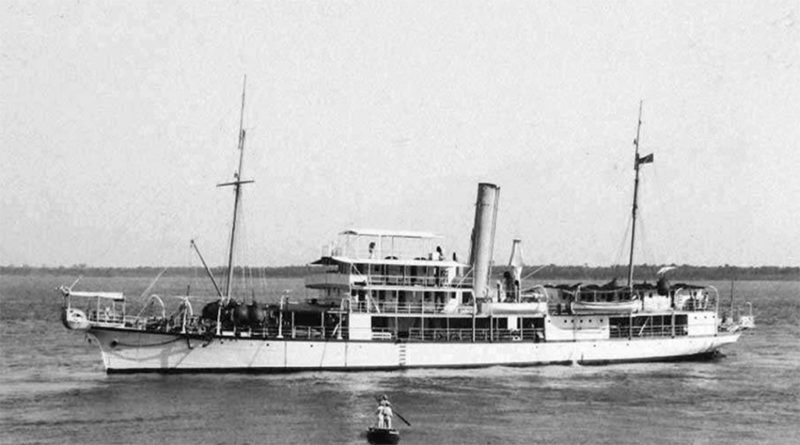

The Viking (above), a 929 grt cable ship for the Amazon Telegraph Company was alongside fitting out. In July 1950 she was wrecked on Mandihy Bank, near Belem on a voyage from Belem to Manaus

Hawthorn Leslie at Hebburn, on the south bank opposite Wallsend was building the large Smolensk (above) of 7,270 grt for the Russian Volunteer Fleet. She was classed as an auxiliary cruiser, one of several ships bought from British yards, although she was basically a troop transport until broken up in Italy in 1922.

Northumberland Shipbuilding Co. was taken over by Sir Christopher Furness in May 1901. He already had a large interest in Robert Stephenson’s shipyard. The Mercedes (above), launched in November, was designed with a revolutionary rig of derricks, and was eventually sold to The Admiralty for £37,250 to act as a collier for the Far East Fleet on the China station. She was subsequently sold to other owners and was lost in October 1936 when carrying iron ore from Spain to the UK.

Charles Palmer ran steel mills and the shipyard at Jarrow two miles downstream from Hebburn. They had for 50 years been the leading builder, but times were changing, and they had closed a smaller yard on the North Bank a year earlier. H.M.S. Russell launched 19th February, of 15,200 tons, was a battleship armed with 12 inch guns. She was sunk off Malta in April 1916 after striking mines.

On 29th August 1901 a sister ship to the British Prince, the British Empire (above), was launched for Gracie & Beazley & Co. for their emigrant carrier service, from Liverpool/Antwerp service to New York. Initially laid up on the river after completion, she was chartered by the Government to carry troops to South Africa.

The Artemisia (above), the last of a quartet of steamers for Hamburg America’s South American service, was completed in March 1901. As German shipyards were at full capacity, the British yards picked up orders that could meet required delivery dates.

Huronian, was a 6,859 grt cargo ship for the Allan Line of Glasgow. Completed in June 1901, she went missing in the North Atlantic in February 1902 when on a passage from the Clyde to St. Johns, Newfoundland with a cargo of coal.

C.A. Parsons Co., who started his marine engine works in 1889 at Heaton, following the famous Turbinia was given their first order, which was to engine H.M.S. Viper, (above) a torpedo boat destroyer and built by Hawthorn Leslie. On 5th August 1901, she was wrecked during manoeuvres in thick fog on Alderney.

Several shipyards on the river were building pontoon floating docks, for customers worldwide in June 1901. Robert Stephenson’s yard completed one for Port Mahon, in Minorca which had a lifting capacity of 12,000 tons and was towed on its 25 day voyage by Smit Tugs.

The remainder of the yards built a range of ships from colliers to tramps and oil tankers, but orders were in short supply leading to empty building berths.

The Tyne’s output for 1901 was 113 ships from 14 shipyards, 310,341grt, slightly down on the previous year, and with work in hand on 81 ships equating to 257,919 grt.

Marine Engineering which was also a major employer with 110 sets of ships engines and auxiliaries built by the 8 builders, totalling 211,550 IHP. North Eastern Marine was the largest producer with 42 sets, followed by Wallsend Slipway Co.

Dry docks were in demand with so much trade, for either voyage repairs or surveys, while there were several dry docks on the river, most companies also had pontoon docks. Smiths Dock at North and South Shields were the largest of the companies. In 1898 Swan & Hunter had applied to Tyne Improvement Commission (TIC) for permission to build and place in Jarrow Slake a large pontoon dock capable of accommodating the largest ships of the day. TIC were still mulling it over in 1901. Brigham & Cowan had also applied to the Commissioners to build a dock. Robert Stephenson at Hebburn, was already in the process of building one 700′ x 90′, one of the largest built at the time.

On 1st May 1901 62 ships were being repaired by the 11 dockyards, Smiths Dock handling 24 ships.

Fishing was another important industry. The Tyne Improvement Commission built a fish quay on the site of an old fish market at North Shields in 1886. At this time there were 10 trawler owners with about 30 vessels. These were generally about 118 feet long with a 22 feet beam, with a 60-70 dwt capacity and manned by a crew of 10. They would trawl the 6,700 square mile Dogger Bank for fish. Numerous local seine netters, and drifters also used the facilities. Generally around 2,600 were employed on the quay servicing the industry, or working in the curing houses where the herring were turned into kippers. During the summer herring season boats from all along the east coast fishing ports would chase the shoals down the North Sea, followed by the fishermen’s wives who worked the quaysides gutting, salting and packing the barrels of fish. Their numbers would swell to almost 6,000 at North Shields. 1901 was a record year for herring, on one day 160 sail and steam drifters made landings at the quay. The total landings for the 1901 season amounted to 4,273 tons, worth £33,000.

Moored off the fish quay was a former Royal Naval frigate. James Hall the Newcastle ship owner, was a man who did many good works in the area, including, with the aid of the Admiralty, establishing the Wellesley (above) as an industrial training ship on the Tyne in 1868 for the education of up to 300 destitute boys un-convicted of crime. This was provided for by the Industrial Schools Act, with boys transferred by the Education Committees, Poor Law Union and voluntary causes, plus those whose parents or guardians wanted to place them under Naval discipline. At the age of 16, over 90% joined either the Royal Navy, Merchant Navy or the army as tailors, buglers or bandsmen. Hall raised the funds needed to equip the ship, which opened in 1869, and was stationed lying off North Shields Fish Quay. The ship had been built in 1844 as H.M.S. Boscawen, a 74 gun frigate, which during her career had been flagship of the North America and West Indies station in 1853, and later in 1857 of the Cape Town base. She was burnt out on 14th March 1914, and subsequently taken to Hughes Bocklow at Derwenthaugh (up stream) later that year to be broken up. Hall was also the prime mover in getting the Government to have some form of ship registration and safety code for the loading of ships, a cause which was taken over by Samuel Plimsoll, who received the credit.

On 24th October the Royal Navy’s Reserve Fleet (10 battleships, 5 cruisers, 14 torpedo boat destroyers, 8 gunboats), passed the river en-route from Rosyth to Great Yarmouth, the torpedo boat destroyers came into the river for bunkers at Jarrow and caused some excitement amongst the local population.

What brought the river its wealth was the export of coal. Early records show that King Henry III granted a charter in 1239 to the Freemen of Newcastle to dig for and export coal to London. By 1600, 400 ships were traversing the East coast with 190,000 tons annually. Up until the invention of staiths in the 19th century because of poor navigation, due to sand bars, islands and little water depth, ‘Keels’ (barges) would bring the coal down river with 21 tons at a time, from the colliery loading spouts to the lower harbour at North and South Shields and then transfer the coal to the numerous waiting collier brigs. It was not uncommon for larger sailing ships to wait outside the river for a spring tide to gain entrance. It was the advent of the railways that forced Newcastle Corporation into action to improve navigation, as at the time they exacted all dues from trade on the river.

They were competing with coal from the south Yorkshire coalfields which could be transported by train to London quicker than sailing ships from the Tyne. The railway networks from the pits were well established, but the bottleneck was at the loading points on the river and how to transport the coal quickly to their customers in the South of England.

Charles Palmer revolutionised the collier trade with the introduction of the John Bowes the first steam driven collier that did away with solid ballast and could do a round voyage to the Thames in the same time as two brigs could do in a month. As a consequence in 1859, the newly formed Tyne Improvement Commission employed a Scottish engineering manager, John Ure, who transformed it totally by excavating, dredging and straightening it over 50 years. Over 106 million tons of spoil, mainly sand and clay, stretching over 14 miles of river course was extracted, transforming it into a workable river by 1900, and dumping it in the North Sea. The first project was to build 2 piers to create enclosed water at the harbour entrance. The north pier was breached during a storm in 1897 and not repaired fully until 1909.

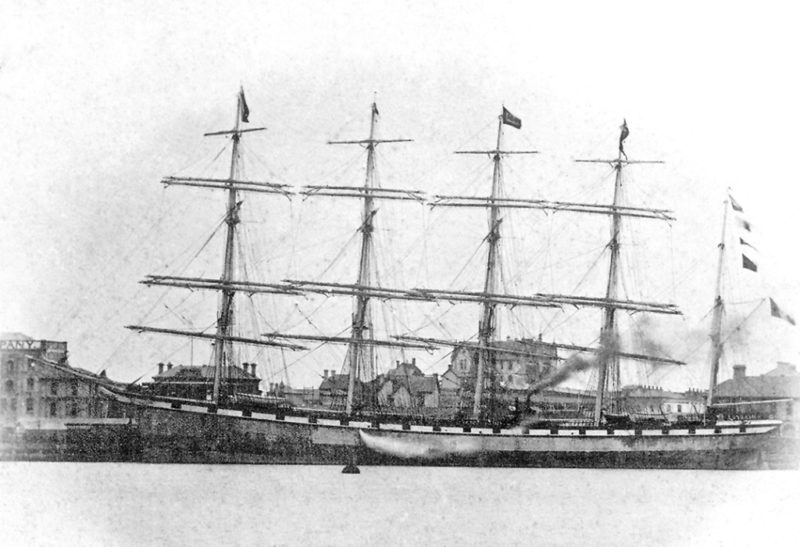

This was still the age of the sailing ship (the bulk carriers of yesteryear) and these were frequent visitors. One the shipowners was A.D. Bordes of Dunkirk, who owned 46 sailing ships.

The company entered into large contracts (typically 16,000 tons) with local colliery owners to buy and transport huge quantities to Valparaiso and other west coast South American ports, returning to the UK with nitrates etc. The largest of these was the five masted France (above) of 3,325 grt and built on the Clyde in 1890. She was a big ship of her type with 49,000 square feet of sail, and 45 crew. She sailed from the Tyne on 14th March with 5,108 tons of coal, worth £50,000. On 13th May she was found on her beam ends after her cargo shifted during a storm off South America.

Other sailing ships were bringing grain and wheat from Sydney NSW (103 days passage), Portland, Oregon and San Francisco (155 days passage), and returning with coal.

As an example of how busy the river was on 1st May 1901, 55 ships arrived in the river, and 67 sailed. Moored in the river were 76 in Tyne Dock, 36 in Northumberland Dock, 2 in Albert Edward Dock, and a further 69 at eighteen other coaling staiths on the river. Along with the 62 ships at repair yards and 5 at Newcastle Quay, this totalled 250 ships packed in. Tyne Dock was also the import point with a constant stream of ships with timber from Scandinavia for use as pit props in the mines, as well as wheat, oats, esparto grass and iron ore.

Three coaling docks were created, Northumberland Dock in 1857, which by 1900 could handle 21 ships at a time, Tyne Dock with 5 acres and 23 miles of railway track, was excavated at South Shields in 1859, and Albert Edward Dock at North Shields, all close to the river mouth in 1884. It would be accurate to say that the primary business of the river centred around the export of coal/coke or supplying bunkers to ships calling at the port. On 30th December 1899 there were 131 ships waiting to load, with only 4 other ships at Newcastle Quayside.

In 1901, 14,933,635 tons of coal and coke left the river in over 12,000 ships. At the start of 1901 freight rates were falling, as the Government released chartered ships from the South African Boer War campaign, therefore not needing as much bunker fuel for the transport fleet. As the war drew to a close 23 ships were laid up on the river.

An unusual cargo was shipped into the river in April when the Norwegian ship Fremmed brought petroleum into the port in barrels.

Newcastle Quayside was still managed by the Council even up to 1900 and they were reluctant to expand the length of the quayside which sat at the centre of the City. At most 7 ships only could berth there. A regular passenger service from the city centre was an 8 shilling single fare, journey to London, taking 23 hours, with Tyne S.S. Co. Ltd.

Other regular traders, included the Cairn Line, and DFDS with a livestock trade to the river. It was also a hub for Scandinavian emigrants, having reached the UK, to take forward passage onto the New World with the Wilson Line, running 3 ships on a regular service.

Runciman’s wanted to start a freight and passenger service to the USA and even went to the extent of offering to buy out an existing shipping company to secure berths. Amongst others who wanted berths was one who wanted to open a service for fruit steamers but due to the Council’s lack of foresight these plans were eventually abandoned.

In 1876 the Armstrong’s designed Swing Bridge at Newcastle was opened, which not only allowed colliers up stream to access newly built staiths but also allowed warships built at Low Walker to pass upstream to Armstrong’s armaments factory at Elswick for their guns to be fitted.

As the demand for coal continued to grow, so did the wealth of the river, with company’s expanding their operations, and subsequently developing the river into one of growing importance. The industrial landscape changed dramatically after the depression of the 1930s and World War II into a leaner and more effective business, whose boom lasted up to the 1980s.

Today the river is a different place, where salmon and trout are fished. The heavy industry has gone, and the trade of the river has reverted to the inner harbour at North/South Shields in the main with massive investments in the infrastructure taking place.

Over 600,000 cars are exported/imported, 625,000 passengers pass through the cruise terminal and there are berths for handling the import of coal in 70,000 dwt bulkers from Murmansk, Hampton Roads etc, which is then transported by rail to the big power stations in southern Yorkshire.

By 2013 over five million tonnes (coals to Newcastle!!) were brought into the Tyne.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item