“I feel instinctively that Providence has created France for complete success or exemplary misfortunes”.

General de Gaulle’s perceptive summing up of the national psyche could equally apply to the country’s principal shipping line. Of all the Atlantic players, none conjured the full spectrum of experiences and emotions, from elation to despair, as dramatically as the French Line.

The Compagnie Générale Transatlantique , abbreviated to CGT or ‘Transat’ in France and universally known as the French Line, emerged as a government funded successor to the Compagnie Générale Maritime, a fledgling shipping company established in 1855, by Emile and Isaac Péreire. Like their contemporary, Samuel Cunard, these sons of Portuguese emigrants were already prominent businessmen, for whom the steamship represented a fresh commercial opportunity.

Using their extensive contacts and influence in banking (they had established much of their wealth and reputation as financiers) and the imperial court, in 1861 the Périere brothers acquired a certain Louis Victor Marziou’s concession to operate a regular steamship service across the Atlantic to the Americas, together with an annual government subsidy of 9.3 million francs. In return they contracted to carry mail, with a guaranteed minimum of 26 roundtrip voyages on the principal service to New York. If the practical purpose was to carry the post, Emperor Napoleon III’s decree at the company’s inception already hinted at a broader commission, “to uphold and maintain the prestige of France on the Atlantic”.

On 16th June 1864 the company’s first ship, Washington, departed Le Havre inaugurating the famous service to New York. Over the ensuing century the utilitarian named home port (literally ‘the harbour’ in English) steadily grew in unison with the company steamers, however its constraints significantly prejudiced CGT’s development.

Washington and her sisters, Lafayette and Europe were built by Scott’s of Greenock. Commercially this made eminent sense, the Clyde was then the fulcrum of the nascent steamship building industry and those French yards that tendered for the contracts were not only more expensive, but also unable to provide the necessary infrastructure, technology or expertise to rival that concentrated in Scotland. Regardless, the political imperative was to build the ships in France, so the Périere’s and the Parisian government came up with a radical solution.

After researching suitable sites, CGT purchased sixty two acres of largely barren wasteland on the northern shoreline of the Loire estuary, encompassing the fishing village of Penhöet and close to the industrial city of St. Nazaire. Local shipwrights were trained by a delegation of John Scott’s workforce (including the great man himself), as Emile Périere’s vision of ‘a mighty and sophisticated workshop’ emerged from the surrounding marshland. Chantiers et Ateliers de Penhoët subsequently became the birthplace of almost all the famed French Line liners and ultimately the very last liner of them all, Queen Mary 2.

At sea and in the boardroom Transat was beset by misfortune in that first decade of trading. There were groundings and collisions but also Emile and Isaac Périere were forced into bankruptcy by the financial crisis of 1868 and consequently relinquished their positions on the board. Two years later, the whole nation was left reeling by defeat in the Franco-Prussian war, the bloody suppression of the ensuing Paris Commune and the unpredictable origins of the Third Republic. Just as the company was re-establishing itself, Ville du Havre, which had originally been completed as Napoleon III, collided with the sailing ship Loch Earn and sank with the loss of 226 souls in November 1873.

In the face of such challenges and despite their close associations with the now discredited Second Republic, CGT’s board once more turned to the elderly Périere brothers for inspiration. Emile died in 1875, but Isaac and in particular his son Eugène, joined the board and would prove instrumental in transforming Transat’s fortunes over the next quarter of a century.

One important milestone occurred in 1882 when the company successfully renewed its transatlantic mail contact and secured the corresponding government subsidies. As a result, planning began for four fast (17.5 knot) 6,700 grt liners, laying down a gauntlet to North German Lloyd’s Aller class and Cunard’s slightly larger Umbria and Etruria. Alas two of the quartet, La Champagne and La Bretagne, suffered inauspicious starts, they both ran aground on launch day in April and September 1885 respectively.

Despite these unfortunate baptisms the two ships entered service to widespread acclaim in May and August 1886. Concurrently the other sisters, La Bourgogne and La Gascoigne, originally laid down as Algerie, were under construction at Forges et Chartiers de la Mediterranèe at La Seyne, near Toulon and left Le Havre on their maiden voyages in June and September of 1886 respectively. As built, the ships had four masts and two diminutive smokestacks. They were mechanically conservative and within a decade they needed new boilers and had to be re-engined. When they emerged from these transformations only two masts were retained, and the funnels considerably raised in height.

The new liners were instrumental in fostering Transat’s reputation for fine dining, attentive service and commodious First Class accommodation. Regrettably, two of the pair also highlighted the company’s unenviable safety record. La Bretagne and La Gascogne enjoyed long and largely untroubled careers but La Champagne was involved in two collisions before finally running aground and breaking her back at St Nazaire during a storm on 28th May 1915. La Bourgogne was even more ill-fated. On American Independence Day 1898, she collided with the sailing ship Cromartyshire in dense fog. In the ensuing melee over 500 passengers and crew perished, the greatest loss of life in the company’s history.

However, this tragedy lay in the future when Transat ordered its next large Paquebôt, arguably the first to fully epitomise those French Line idiosyncrasies and, for the purposes of this article, the first true seagoing manifestation of La Belle Époque.

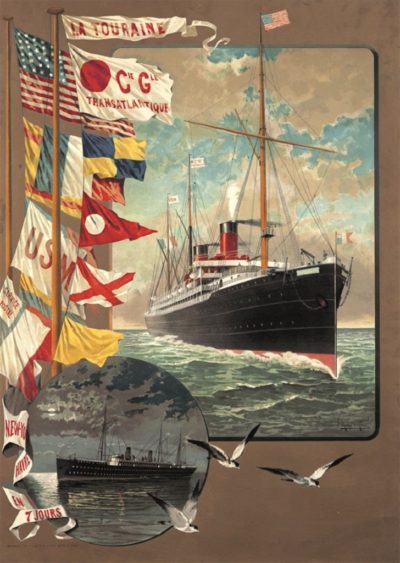

Designed by CGT’s foremost naval architect, Monsieur V. Daymard, La Touraine was launched into the mouth of Loire on 21st March 1890. Thousands had already become acquainted with what the new ship would look like the previous year. They attended CGT’s pavilion at the Paris Exposition Universelle, nestled alongside the Seine in the looming shadow of the World Fair’s star attraction, the Eiffel Tower. A contemporary newspaper describes the exhibit:-

“On entry, you find yourself on the staircase of a great steamer, whose two principal decks you visit in sequence. It is the exact reproduction, life size, of the steamship la Touraine which is under construction. Eleven dioramas, the work of Messieurs Poilpot, Hoffbauer, Montenard and Motte, display to you the luxurious accommodation of a great Transatlantic liner, the salons, the smoking room, the passenger cabins. To one side are reproduced several fascinating scenes: the arrival of a steamer in New York, views of the principal ports used by the Compagnie Transatlantique, their immense dockyards.”

Although still constrained by the locks and sinuous entry to Le Havre, the new ship had impressive dimensions. With a length overall of 163.1m (536.9ft) and a beam of 14.53m (56ft), the 8,863grt La Touraine was the sixth largest ship then in existence (only Brunel’s Great Eastern, Inman Line’s recently completed City of New York and City of Paris and White Star’s equally modern Majestic and Teutonic, were larger) and sailed for New York from the appropriately named Quai des Transatlantiques on 20th June 1891.

Whilst clearly an evolution of the earlier quartet, the new ship presented a more modern and particularly handsome profile. The long, low hull was topped by a two deck high superstructure and a pair of relatively short, evenly spaced funnels. As built, she sported three tall masts with auxiliary sail. The sails were never unfurled. They had been cautiously incorporated by the builders as insurance against mechanical mishaps, but with two engines and corresponding screws, canvas assistance was no longer a requirement.

She certainly didn’t need them for speed. La Touraine was powered by two, 3 cylinder Triple expansion engines sited in a 15.4m (50ft) long engine room. Steam for the engines was primarily supplied by six (three double and three single) boilers located in a central boiler room. Supplementary boilers were housed in a smaller compartment further forward. Consuming 254 tons of coal per day (240 tons for the main engines, the residual for auxiliary machinery) fed by stokers into 45 furnaces, the boilers generated up to 85 tons of steam per hour. Developing 3,250shp the engines were harnessed to a pair of 53m (173ft) long, 93 ton propeller shafts, that turned the 6m (approximately 20ft) diameter, three bladed screws to propel the new vessel at a service speed of 19 knots. Although she never captured the much prized Blue Riband, La Touraine was nevertheless one of the fastest liners of her era.

Six days, seventeen hours and thirty minutes after Captain Frangeul had presided over her maiden Le Havre departure, La Touraine entered New York harbour to an enthusiastic welcome. She was an instant success, reputedly excelling in the basic prerequisites of speed and stability, but, in First Class at least, also offering something less tangible, what might be referred to as the gallic joie de vivre, which her German and British rivals could never emulate. Certainly a combination of geographic, linguistic and political factors conspired to ensure that fewer emigrants used the French Line than their German or British rivals. Consequently, whilst Cunard, White Star, Hamburg America and North German Lloyd all offered luxurious first class accommodation, it was a façade for the true source of profits, the hopeful emigrants languishing in the confines of steerage. For Transat, First Class was the life blood of the company. It was a subtle but crucial distinction.

La Touraine’s accommodation initially reflected these priorities, with a proportionally high 392 First Class passengers within an overall capacity of 1,090. Those occupying her thirty appartements de luxe, six appartements de grand luxe, and her smaller and more modest First Class cabines, enjoyed what was widely reputed to be the finest dining experience afloat. Epicureans abounded amongst her passenger lists and a rather clichéd but enduring legend was born, that the quality of cuisine onboard French Line ships attracted more seagulls and sharks than any other shipping company

Her décor and public rooms in First Class were similarly fêted. The Escalier Grande (main First Class staircase) was wrought from carved mahogany and renowned for its huge mirror, not only allowing those descending a final check of their attire, but also exaggerating the overall sense of spaciousness and reflecting the artworks that adorned the stairwell.

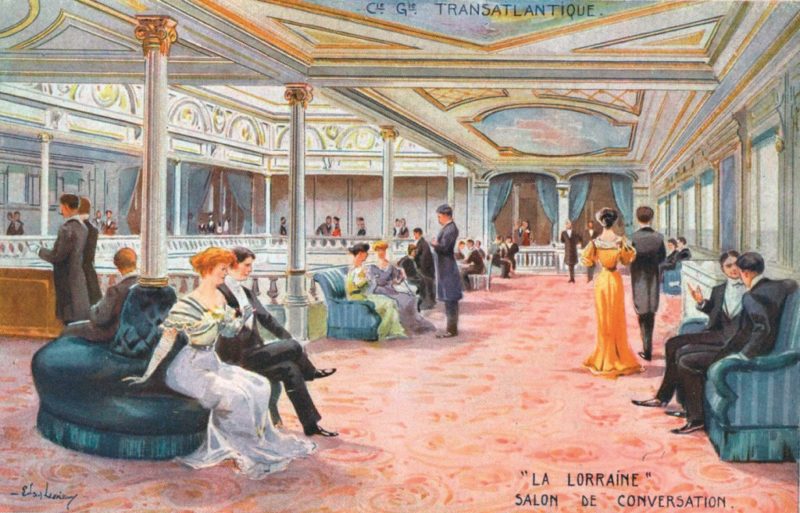

In September 1891 a 23 year old American, Theodore W. Pietsch, boarded La Touraine at the French Line’s Pier 42 bound for Le Havre. His account of that crossing is published at www.searlecanada.org (page 82) and provides an excellent, if perhaps overly effusive impression of life onboard. Of the Salon de Conversations (First Class Lounge) he states, “Is not this a beautiful expression of the style of Louis XVI? What a soft and delicate treatment! What a sense of color required by the artist who composed those intricate and dainty inlaid panels that adorn the walls! What rich and costly woods, from India, Persia, and Japan, and above all, what a delightful arrangement for the convenience, comfort and pleasure of those fond of company, books and music!”

Describing the dining salon, Pietsch writes, “What a large and spacious room it is, so amply lighted on either side and from the great skylight above, and arranged for the accommodation of so many without sacrificing the comfort of one! The room is decorated in reds, browns, greens, and golds. Elegant tapering Corinthian columns support the balconies above. At one end is the great fireplace and mantel, and opposite the elaborate sideboard. Smaller buffets adorn the angles and recesses.”

Whilst some smaller family groups lined each flank, Captain Frangeul presided over his centrally located, eponymous table, which ran the length of the room. By all accounts, including Pietsch’s, the Captain was as congenial a host as any of his much vaunted French Line successors.

Reflecting the social norms of the period, (which prevailed well into the next century) male First Class passengers would repair to Le Fumoir after dinner, where “……..the gentlemen of the poker clique played incessantly, others read, drank and smoked and lounged on the comfortable armchairs and cushions. A staircase communicated direct with the cabins above, which was often very convenient.” In French even the Smoking Room’s name was predictably masculine!

Amongst the most popular innovations championed by the French Line on La Touraine were her electric lights. After years of dimly flickering candlelight or nausea inducing oil lamps, one can imagine how welcome the steady, odourless and bright glow of electric light was. Publicists were keen to impart that the ship boasted 300 incandescent lamps of 16 candlepower and 572 of 10 candlepower, for an impressive total lighting distribution equivalent to 10,520 candles.

The splendid columns, intricate marquetry and fine dining that seduced the upper echelons of the passenger list were of course absent in the bare steel dormitories of steerage. Nevertheless, La Touraine offered superior facilities to her predecessors in this regard, all of course lit by the electric lamps. Although La Touraine quickly settled into the Atlantic schedules she also gained fame and notoriety by offering the company’s first long distance cruise. In 1894 she sailed from New York to the Eastern Mediterranean, ultimately terminating at Constantinople, capital of the waning Ottoman Empire before returning to the United States.

A year before that famous cruise the Bulgarian writer and humourist, Aleko Konstantinov, crossed to New York on La Touraine. His observations were included in a travelogue entitled ‘To Chicago and Back’. Perhaps more realistic than Pietsch, his comic depictions give a colourful and informative insight into life onboard the French Line flagship in the late 19th century, much as Charles Dickens achieved in ‘American Notes’ (when recalling his crossing on Britannia) almost fifty years previous. Sea sickness features prominently in both memoirs (Dickens as sufferer, Konstantinov as observer) as do the varied, cosmopolitan and frequently odd personalities amongst their fellow passengers. People watching was indeed a compelling pastime.

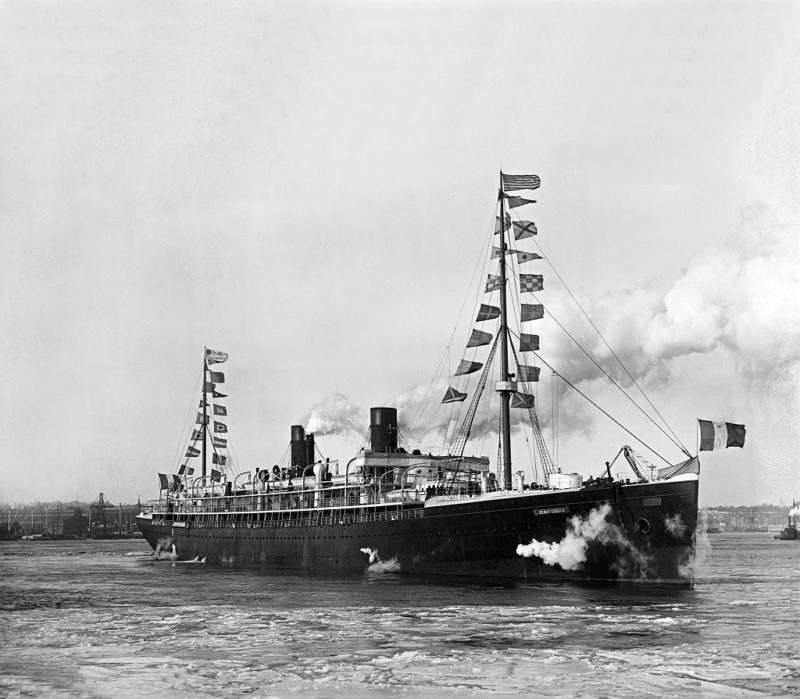

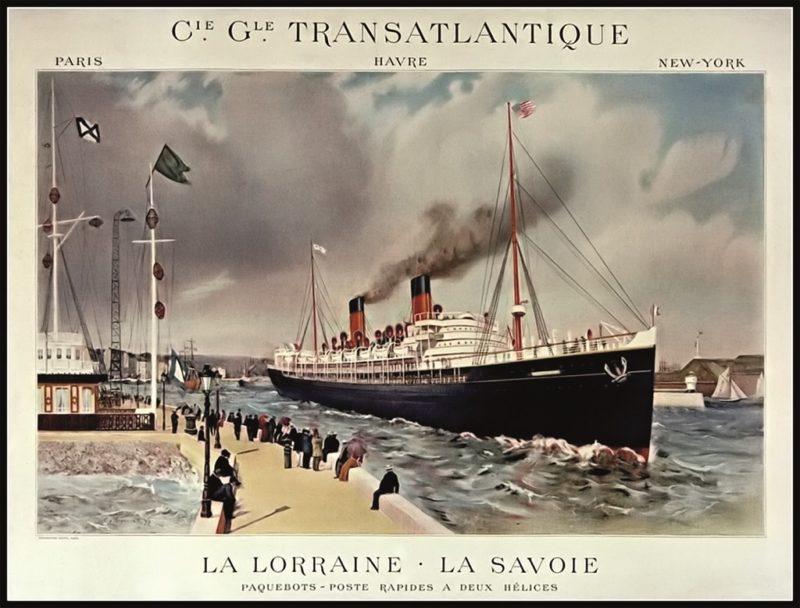

Konstantinov describes a typical day at sea. At 7am the ship’s bell provided a universal alarm call, inviting passengers to coffee in the dining room. Reading and games (draughts, chess, backgammon etc) in the smoking room were the staple distractions but anything exceptional (ship, bird or fish/whale) drew significant crowds, weather permitting. Also weather permitting, mealtimes represent a high point, punctuating the day at 10am (Breakfast, including an excellent Bordeaux wine!), 1:30pm Lunch (which Konstaninov rather dryly refers to as ‘more a laxative than food‘) and 6pm, when diners are called to the first of two dinner sittings. As the seven day voyage progresses and fellow travellers find their sea legs, the ship comes alive with music, dancing and general bonhomie. Earlier, in a paragraph starting, “Let me acquaint you briefly with the ship” he expounds the ship’s exceptional size but also, intriguingly the clear-cut class distinctions. Having provided a deck by deck summary he concludes, “What exists below that I do not know. It must be storerooms and the lodgings for the third class passengers.” Finally, he describes La Touraine’s entry to New York, marvelling at the Brooklyn Bridge, if not quite so impressed by the Statue of Liberty.La Touraine’s success and the introduction of new, larger rival tonnage, prompted CGT to order two somewhat larger near-sisters towards the end of the 1890s. Significantly they would be the last large ships built ‘in house’ before the company divested itself of the Penhöet shipyard. The first of the twins, La Lorraine, was launched on 20th September 1899. Almost 50ft longer (176.5m or 580ft overall) and 4ft broader (18.26m or 60ft overall), than La Touraine, the new flagship had a gross tonnage of 11,146, making her by some margin the largest vessel in the CGT fleet but still considerably smaller than contemporaries Kronprinz Wilhelm and Deutschland. Le Havre once more was the restricting factor.

La Lorraine made 22.5 knots on her trials in the summer of 1900 and there was huge excitement in the port city as she departed on her maiden voyage, under the command of Captain Alix, on 11th August 1900. Unfortunately, mechanical issues plagued that first crossing and she was promptly returned to the builder’s for remedial work. The timing was less than propitious. Just three months later La Touraine was returned to St Nazaire to begin a thirteen month refit, finally emerging in January 1902 with the middle mast removed, extended bilge keels to improve stability (somewhat belying her earlier reputation as ’the steady boat’) and her machinery thoroughly overhauled. Her accommodation was also revised, increasing third class steerage capacity to 1,000. The changes resulted in a reduction in size to 8,429 grt.

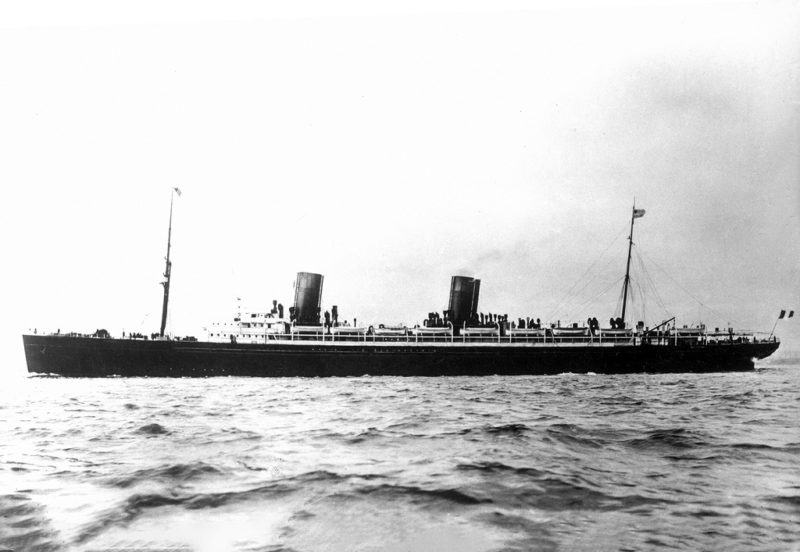

By the time La Touraine returned to the fold La Lorraine’s teething problems were resolved, although she would remain a ‘tender‘ ship for much of her career. In the interim she had been joined by a sister, La Savoie, which first sailed for New York under Captain Poirot on 31st August 1901. The three ships spearheaded CGT’s North Atlantic service from Le Havre, supplemented by L’Aquitaine and La Gascogne.

Any hope that the company could now settle into a period of stability and growth were dashed on 21st January 1903 when fire raged through La Touraine at Le Havre. Having finally extinguished the flames it was apparent that much of the First and Second class accommodation, including the magnificent grand staircase, dining salon and most of the deluxe cabins were charred and destroyed. She returned once more to her builder for renovation and further enhancements, emerging reputedly better than ever. Two years later she would carry an 18 year old Polish born pianist called Arthur Rubenstein on his first venture from Europe to the United States.

Whether more widely reported than her consorts and contemporaries, or simply more ill-favoured, La Savoie seemed to arrive storm battered at New York repeatedly in that first decade of the 20th century. One month after La Touraine’s fire, she limped into New York a day late after encountering a huge sea in mid-Atlantic that damaged her bridge and smoking room. Worse was to come in the spring of 1907. Having departed Le Havre on Saturday 2nd March 1907 she encountered a series of gales on her passage west, before being struck by ‘a monster wave’ the following Thursday. Estimated at about 50ft high the wave struck the port bow, smashing the heavy oak door thereby allowing seawater to pass unhindered along the corridor outside the smoking room, where occupants were thrown to the floor and subsequently soaked through. Cascading down the grand staircase the wave swept into the dining salon and numerous cabins and suites which ‘were flooded to a depth of several feet’. Captain Tournier hove the great ship to and she drifted for the next eight hours whilst the damage was assessed, before recommencing her voyage. When sorting through the chaotic piles of debris and flooded interiors, crew members established that the heavy iron stairwell between main and promenade deck had been torn away and taken by the sea. The corresponding newspaper report commences in a distinctly understated manner ‘The French Line steamer La Savoie, carrying more than 1,000 passengers arrived here today after a thrilling experience in rough weather at sea’.

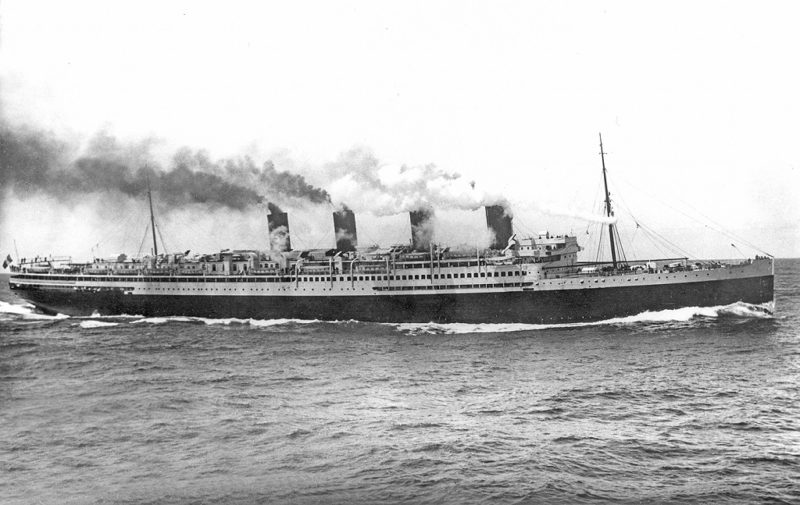

La Lorraine and La Savoie were joined by a larger, faster consort in 1906. La Provence was the first major new build to be introduced under the expansionist presidency of Jules Charles-Roux. Launched on 21st March 1905, she departed for New York exactly 13 months later. Like her siblings, the new ship had a distinctive, elegantly balanced profile of two evenly spaced funnels and masts. However it was her interiors, designed by the firm Nelson, that brought enduring fame. Within her considerable hull she combined a mix of austere and deluxe accommodation for 422 first, 132 second and 808 third class passengers.

A contemporary article about the ship begins, ‘This story is that of luxury, the installations are princely, luxurious cabins, first class cabins, saloons for the wealthy’. It continues, ‘The great care taken for the wellbeing, convenience, and health of the travellers, is worthy of note on the Provence’. Accompanied by a portrayal of elegant Edwardian ladies and gentlemen playing shuffleboard the writer states, ‘There is neither rain or sun to fear, the tent-deck is near to shelter you from the wind blowing either tribord or babord, the central construction offers you a ready shelter’.

First class enjoyed use of the richly decorated Salle à Manger, a reproduction of that found in the Duke de Soubise’s Parisian residence. ‘We can at our leisure, enter by two large glass folding doors. It is indeed a splendid room, looking quite majestic with two hundred and two places, two hundred and two large comfortable arm-chairs.’ Deck head beams were rendered in cut crystal set in gilt bronze frames, ornate chairs were upholstered in red velvet with matching curtains for the ‘two and twenty large rectangular windows, through which air and light come flowing in’. Each table was also illuminated by intricate Louis XV style gilt bronze chandeliers. Similarly sumptuous was the main lounge in the style of Louis XVI, frequently referred to as the Salon de Musique on account of the ship’s resident orchestra (a company first) and central dance floor, bathed in light from the ornate glass dome. With its peach coloured walls featuring red marble inlays, peach and gold pillars and long green drapery, the room was both distinctive and elegant. Also worthy of special mention was the renaissance style smoking room or Le Fumoir with cedar, lime wood and raised tan leather panelling. Reflecting the prevalent attitudes of the time, the description concludes, rather patronisingly, ’The ladies are quite at home in their sitting-room below, whereas the gentlemen have their smoking room above’. With their own specially designated nursery and dining room First Class children on La Provence were similarly well catered for, ‘…….and when the weather is bad, that they cannot go to the grand deck, they have perfect air and room enough to run about and play merrily. Indeed it is not a dull place, especially in winter, perhaps it is the lively on the boat.’ All first class accommodation was linked by the now requisite teak grande descente supplemented by another novelty, a lift. ‘To make a lift onboard a ship is not without a certain boldness of conception’, our guide rather obviously observes.

Having descended to the crew, second and third class areas the writer continues, ‘We will not leave the between-deck without giving a glance, to the front and back that contain in one-way or another things that are most interesting. In front, are the crew’s posts, sanitary places, including three hospitals, the infirmary, the pharmacy, and the two isolated rooms for contagious disease, for all must, of course, be foreseen’. They describe the steerage quarters in glowing terms, ‘One thing strikes you as you go over the labyrinth of passages and “streets” of this floor. It is the perfectly well aired, and incessant activity and the greatest cleanliness that reigns from one end to the other, and what is also worthy of notice is the many waterspouts placed from distance to distance, all in proper order.’ In truth steerage quarters continued to be Spartan, with straw filled palliasses serving as mattresses that were emptied overboard the last morning onboard as each coast approached. Nonetheless, in addition to the electric light and flowing water, cooking facilities and utensils were provided by the company.

Entertainment, in all classes, remained similar to that related by Aleko Konstantinov a decade earlier, but the advent of wireless communication (La Provence was the first company vessel to incorporate a télégraphie sans fil (TSF) set), meant that news from each shore could now be received onboard. To relate these current affairs, together with topical articles pre-printed ashore, the French Line produced a free newspaper, appropriately called L’Atlantique, which remained a company institution for the next 70 years.

Despite her numerous attributes La Provence remains largely unknown outside France, which is indeed a travesty. The primary reasons for this emerged simultaneously on the banks of the Tyne and Clyde whilst she was under construction. At over 30,000 grt and 787ft in length, Cunard’s Lusitania and Mauritania dwarfed their cross-channel contemporaries and their innovative turbine machinery harnessed to four screws left La Provence in their wake.

Nevertheless La Provence’s triple expansion engines gave her a highly credible top speed of 23.45 knots on sea trials. On her second crossing, she famously beat the incumbent westbound Blue Riband holder, Deutschland, leaving New York 15 minutes later than her Teutonic rival and sweeping south of Lizard Point four hours ahead. Indeed under her first master, Captain Alix, La Provence completed the fastest (to that time) crossing between Le Havre and New York on 14th September 1907, at an average speed of 22.08 knots.

The four ships, La Touraine, La Lorraine, La Savoie and La Provence created a balanced express fleet and although superseded in size and speed by British and German tonnage, they firmly cemented the French Line’s enviable reputation for high living at sea. However company President Charles-Roux had no intention of resting on these laurels. They would be joined by an even larger new flagship at the beginning of the following decade, a vessel that in name and spirit fully represented her nation of birth.

Protracted negotiations between shipping line and shipyard started in 1907, but it wasn’t until February 1909 that the first keel plates of the 218.83m (719ft) liner were laid on the building slip at Penhöet. At 24,666 grt she dwarfed her prospective fleet mates and was initially allocated the name La Picardie. In terms of size, machinery and even interiors the new ship represented a quantum leap forward, tangible evidence of Jules Charles-Roux’s limitless ambitions for the company. Ultimately the project was also facilitated by the inauguration of a new deep water berth and Gare Maritime on Le Havre’s Quai d’Escale, which was opened by the republic’s incumbent President Jules Fallières and first used by La Provence in 1906. Protected by a breakwater this allowed ships to enter, turn and dock in the Avant Port, without necessarily having to negotiate the locks and sinuous turns of the Bassin de l’Eure.

La Touraine returned to Penhöet for a further significant refit in 1910. When completed her capacity remained similar but the demarcation of her accommodation had been significantly revised, First Class now catered for just 69 with 263 in second and 686 in third. Meanwhile, rising above the shipyard infrastructure was the new flagship, which would be reassigned the name of a thirty five year old veteran, recently retired and sent to the scrap yards of Dunkirk in July that year.

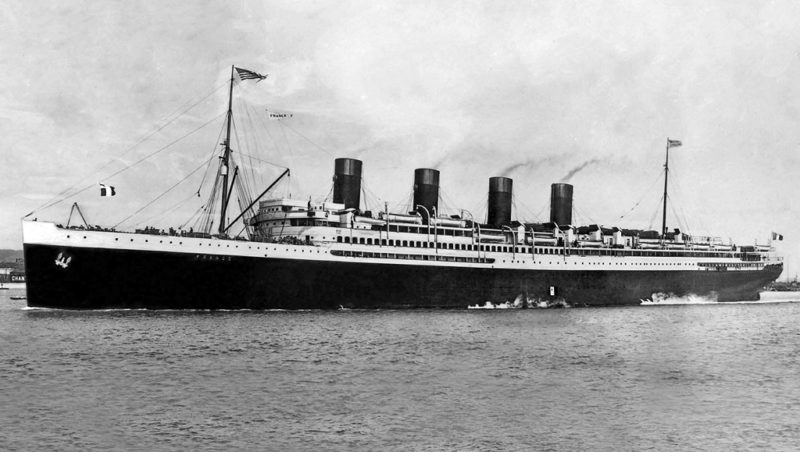

On 20th September 1910, amongst predictable pontificating and pageantry the vast hull was named France and launched into the Loire estuary. It was an appropriate baptism for a vessel that would (amongst a plethora of others), earn the sobriquet ‘Chateau of the Atlantic’. Eighteen months later, delayed by a bunker fire, the completed France left Penhöet for sea trials in the Bay of Biscay.

She possessed a distinctive profile, the most famous elements of which were those four, rather squat, cylindrical funnels. As the only non-British or German entry in the exclusive four-stacker club France would always be unique, but she also wore those funnels in a singular fashion, evenly spaced (à la British) but without the rake of her cross-Channel rivals. Perhaps the most noteworthy element of her look was the superstructure, which ran almost unadulterated from the bridge to the stern, not unlike many modern cruise ships. In part this was an optical illusion, a result of the upper deckhouses being painted dark brown and the lower than usual delineation of the black hull and white superstructure. The livery emphasised the long, low and distinctly horizontal visual appearance of the ship.

Shipyard and company engineers who embarked on those sea trials with a certain trepidation returned triumphant. Having experimented on a series of smaller vessels, they developed and installed, under license from Charles Parsons, the first set of triple expansion marine turbines to propel an Atlantic liner. The four units received steam from nineteen boilers, which were in turn fed by 120 furnaces consuming between 650-720 tons of coal per day (notably more efficient than the Cunard flyers). It was a complex arrangement, with the inboard shafts connected to a pair of low pressure turbines, whilst separately located high and intermediate turbines drove the outer shafts. The turbines generated a maximum combined 47,000shp (2,000shp less in normal service) and were coupled directly to the quadruple shafts. These rotated at 250rpm and drove 12ft 6in diameter propeller blades to a maximum 25 knots, well in excess of the 23.5 knot contract service speed. France earned the accolade ‘best of the rest’, only exceeded by the record breaking Lusitania and Mauretania.

France first arrived in Le Havre on Saturday 13th April 1912, to a jubilant welcome and a terminal festooned with bunting. The previous evening, out in mid-Atlantic, La Touraine had been telegraphing, to those that could and would listen, ice warnings to all shipping, including a certain White Star liner making her maiden crossing. Early the following week the festive mood in Le Havre evaporated when the first reports reached Europe confirming the loss of Titanic and over 1,500 lives. Inevitably a more sober atmosphere pervaded the ship on Saturday 20th April as Captain Poncelet guided France out of the port city on her own maiden voyage. To reassure nervous passengers, the company widely broadcast that she would be sailing the most southerly track to avoid ice fields, and that there were (supposedly) sufficient lifeboats and life rafts for all onboard.

Tentatively or not, those first passengers embarked on a ship of superlatives. Comparisons with the famous Chateaux of Versailles and the Loire valley were not mere hyperbole and it has been said that metre for metre, France was the most lavishly and expensively decorated transatlantic liner of them all. Two rooms stand out. First there was the opulent Grand Salon, where the predominant white and gold décor, the Corinthian columns and marble fireplace, were complemented by ornately carved furniture, upholstered in red silk fabrics and lavender blue carpet. The room was presided over (one at each end) by two portraits of Louis XIV, whose ostentatious style pervaded every element of the room, including the large bay windows, copied from those in the chapel at Versailles.

Then there was the three deck high Dining Room. ’A low ceiling does not encourage appetite’ one company brochure expounded, and the central ornate dome, eight meters above the floor was testimony to this thinking. In fact most diners were accommodated on each flank, where two separate decks lessened the hauteur. Gone were the long tables and fixed seating of earlier liners, replaced by the assorted mix of double, quadruple or larger circular tables that was becoming fashionable at the time. The two floors were linked by a magnificent T-shaped staircase, carpeted in blue and copied from that in the Hotel de Toulouse.

Dominating the wall behind the staircase was a painting by Gaston La Touche. Entitled ‘French Grace’ it depicted a group of women leaving a carriage to embark on a boat, before a utopian scene of swans and cascading fountains. La Touche was also commissioned to complete a painting on the ceiling, representing images of France including Notre Dame, the Panthéon and Champagne vineyards. Overall it was justifiably considered a fine setting for the finest dining experience afloat.

One other, much smaller First Class public room worthy of mention was Le Salon Mauresque, or Moorish Room. This fashionable smoking lounge was fitted out in the style of a Moroccan living room, complete with mosaic tiled walls, silk rugs underfoot and an intricately carved ceiling. Maintaining the theme, authentic North African coffee was served by crew members sporting Fez’s and pantaloons, whilst for refreshment passengers could take iced water from an elaborate fountain.

Flaunting the nation’s riches and confidence, both home-grown and from her colonial territories abroad, the France was perhaps the ultimate maritime expression of La Belle Époque at sea, combining the best French artistic and engineering attributes of the era. Nevertheless she had her flaws. Early passengers, including aviation pioneer Louis Blériot, diplomatically praised her sea keeping qualities, but several thousand francs worth of smashed crockery on that maiden crossing was evidence of her alarming tendency to role, even in benign seas. Then there was the vibration. Rattling and rolling, France managed just two round trips to New York before a national seaman’s strike caused her to miss the entire summer season. In defiance of the industrial action CGT enlisted government assistance and naval personnel to ensure La Provence sailed for New York with the mails. France’s reputation for fine living would have to wait until later in 1912.

Replacement inboard propellers and extended bilge keels were installed at Harland and Wolff‘s Belfast yard, which resolved (to some extent) France’s early problems, whilst also adding half a knot of speed. First Class on France became de rigueur for millionaires and the smart set on both Atlantic seaboards, whilst westbound crossings generally drew a full contingent to emigrants in Steerage. Over the next two years she and her fleet mates continued to profitably ply the Atlantic sea lanes. In October 1913 La Touraine gained fame as one of eleven ships that rescued passengers from the burning wreck of the Royal Line steamer Volturno in mid-Atlantic. Hampered by gale force winds and rough seas the French Line crew had bravely taken onboard 40 survivors. By then the twenty two year old veteran had been reassigned to the Le Havre, Quebec and Montreal service.

The confidence and gaiety, the sense of expansion and innovation that had illuminated more than three decades of French and European history, would be brutally quashed the following year. La Belle Époque was to be subsumed by La Grande Guerre. On 4th August 1914 France sailed from Le Havre for New York, filled with Americans desperate to escape the European conflict. The numbers were so high that officers were obliged to give up their quarters to provide additional berths. The following day La Lorraine backed out from her Manhattan pier with 2,000 reservists onboard, amidst an emotional and rousing rendition of La Marseillaise. Elation and innocence were soon replaced by despair and death on an unimaginable scale.

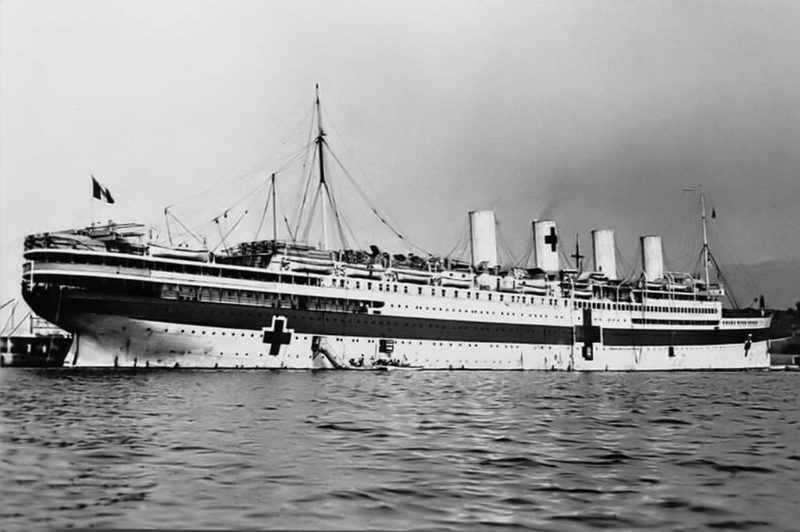

The French Line’s principal ships were rapidly called up and converted for military purposes, except for La Touraine which maintained an austerity service between Bordeaux and New York for the duration of the war. The remainder were partially renamed, dropping their definite articles and acquiring Roman numerals as Lorraine II, Savoie II, Provence II and France IV. All four were initially converted into armed auxiliary cruisers, but in 1915 took up trooping duties. It was in this capacity, on the 26th February 1916, whilst passing sixty five miles off Cape Matapan on the southern tip of the Peloponnese, that Provence II was intercepted and sunk by the German submarine U-35. Barely half of the 1,800 troops onboard were rescued. The loss of the ship and so many young lives somehow symbolised the loss of La Belle Époque itself. In a cruel irony the U-boat commander who ordered those torpedoes to be fired was Kapitänleutnant Lothar von Arnauld de la Péreire, a distant relative of the French Line’s founding brothers.

It was, perhaps an illusion, nevertheless the late 19th and early 20th century would be characterised throughout Europe as a period of stability, prosperity and optimism. Nowhere was this more evident than in France, a nation that in the previous one hundred years had witnessed the rise and dramatic fall of its status under two distinct Napoleonic eras, bracketed by a pair of convulsive revolutions. As it recovered from the humiliation of defeat in the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War and , the nation evolved a new found self-confidence. This was evidenced through cultural, scientific and artistic developments and further refined by colonialism, the ‘land grab’ that projected European influence overseas. It is a sensitive topic but also perhaps more complex and nuanced than it is often perceived. For all their undoubted exploitation and oppression, characteristics for which they are rightly criticised, the colonial powers invariably brought enhancements, amongst them infrastructure and education. Whether misguided or not, in projecting its technological and cultural influences overseas, whilst also undoubtedly assimilating indigenous influences in return, France on the cusp of the 20th century was increasingly self-assured.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item