300 Years A Port

by Nicola Lisle

Liverpool’s first dock was built 300 years ago, in 1715, and was a major factor in the city’s rapid expansion into a port of national and international importance. already a world player in the oceanic trade, the establishment of the world’s first series of interconnected docks during the 18th and 19th centuries saw Liverpool become second only to London in size and importance. For 200 years, the port of Liverpool held world domination in the cotton and slave trades, was one of the main passenger ports during the mass emigration of the 19th century and played a crucial role in the industrial revolution.

A rapid decline in the 20th century brought an end to Liverpool’s heyday, but it is still one of the busiest ports in the UK, handling over 30m tonnes of cargo annually, and is home to a number of shipping lines, notably the Bibby Line and the Danish-owned Maersk Line. ongoing regeneration of the old docks area into a major tourist, retail and leisure area is helping to ensure that the port continues to thrive.

Early History Of The Port

Looking around Liverpool today, it is hard to believe that this was once a tiny, insignificant village, nestling on the eastern banks of the river Mersey and surrounded by agricultural land. The main port in the area was Chester, which lies about 25 miles to the south at the mouth of the river Dee.

It was King John who recognised the potential of the settlement around the ‘pool’, a natural, mile-long tidal inlet, and he created a borough by royal charter in 1207. But it wasn’t until the early 17th century that the town began to show any real growth. as the river Dee began to silt up, Chester’s fortunes declined and Liverpool began to prosper in its wake. Soon Liverpool had taken over from Chester as the main trading port with Ireland. This was to be short-lived, however, as the Irish rebellion of 1641 devastated the country, resulting in widespread famine and plague.

Undeterred, Liverpool began seeking its fortune elsewhere, and quickly established trading links with the West indies and the American Colonies, importing and selling sugar, tobacco, grain and timber. as Liverpool’s commercial activity expanded, so a local shipbuilding industry began to flourish, becoming another important factor in the town’s growing prosperity. By the turn of the century, Liverpool had a fleet of 100 ships, and several shipyards had sprung up around the Pool.

For centuries the Pool had served as Liverpool’s natural harbour, but now it was becoming clear that it was too small and inconvenient, with the larger ships running the risk of being grounded or overturned at low tide. Something larger and purpose-built was needed.

The Beginning Of Liverpool’s Docks

After obtaining an act of Parliament in 1709, London engineer Thomas Steers sectioned off part of the Pool to produce the world’s first commercial wet dock at a cost of £12,000. its brick walls and wooden gates ensured a constant level of water in the dock, unaffected by the rise and fall of the tide, and it was spacious enough to accommodate 100 ships. The dock – later known as old Dock – opened in 1715, although it was not completed until 1720. its close proximity to the town centre meant that cargo could be unloaded close to the warehouses, thereby increasing speed and efficiency. its success spearheaded an even greater rate of growth for the town, and many of the later docks in Liverpool and elsewhere were modelled on old Dock.

After the opening of old Dock, the main focus of shipbuilding activity moved to the Mersey Strand, on the site now occupied by Albert Dock. Here Liverpool’s shipbuilders built merchant ships and warships for the royal Navy, all constructed from wood, and this continued well into the 18th century. During the American Civil War of 1861 Liverpool’s shipbuilders were commissioned to build blockade runners for the American Confederacy. The first of these, Banshee, built in 1863, was the first steel ship to cross the Atlantic.

It wasn’t long before old Dock became a victim of its own success; within 20 years it had become too small for Liverpool’s burgeoning commerce, and in 1736 Steers oversaw the construction of Salthouse Dock, as well as adding a Custom House, dry dock and pier to old Dock. By the mid- 18th century the number of ships sailing in and out of Liverpool had doubled, and over the next 50 years further docks were added – George’s Dock in 1771, Manchester Dock in 1780, King’s Dock in 1788 and Queen’s Dock in 1796. at around the same time a huge number of warehouses were built alongside the docks.

In the 1820s, The Stranger in Liverpool guidebook commented on the “number and extraordinary magnitude of the warehouses“ and that the docks, “so admirably constructed for convenience and dispatch of business”, made Liverpool “one of the most convenient ports in the world”.

With this intricate network of docks came the need to juggle with the tides. Dock gates could only be open for around nine hours each day, when the waters were high enough for vessels to pass through safely, and in that time ships had to enter the dock, load and unload their cargoes, refuel and undergo any necessary cleaning or repairs. Dock masters and gatekeepers had to ensure that the largest ships were moved at high tide, when the river Mersey was at its deepest, with the smallest boats able to be moved at the lowest passable levels. it was a complicated and demanding task, but necessary to ensure efficient operation of the docks, especially as the volume of traffic increased dramatically throughout the 18th century and by the end of the century, 5,000 ships were passing through Liverpool’s docks annually.

Liverpool And The Slave Trade

The murkiest part of Liverpool’s past is its involvement in ‘black gold’, otherwise known as the slave trade. For more than a century Liverpool ships sailed to West Africa and exchanged goods for enslaved Africans, who were then carried across the Atlantic in appalling conditions to be sold. The ships would then return to Liverpool laden with sugar, cotton, coffee and tobacco grown on the slave plantations.

It wasn’t long before Liverpool had the somewhat dubious reputation as European capital of the transatlantic slave trade, eventually achieving world domination. Towards the end of the 18th century Liverpool had over 130 ships involved in transporting slaves, compared to London’s 17 and Bristol’s 5. Liverpool‘s international Slavery Museum estimates that Liverpool alone was responsible for the transportation of approximately 1.5 million slaves on 5,000 voyages, the majority of these to the Caribbean, but also making around 300 voyages to North America, particularly the Carolinas, Virginia and Maryland.

Liverpool merchants were also involved in buying and selling slaves, and many of the town’s most beautiful, elegant buildings were constructed from wealth created by the slave trade.

The chief departure point for the slave ships was George’s Dock, which stood on the site of the current Pier Head buildings, erected during the 20th century and now among the most famous sights in the city. Two dry docks for repairing slave ships were also built in front of the current great Western railway building.

The abolition of the slave trade in 1807 caused shockwaves around Liverpool, as their chief source of prosperity suddenly came to an end. But a new, equally profitable industry was just around the corner, as the 19th century ushered in a period of mass emigration.

Liverpool As A Passenger Port

A changing political landscape, combined with the promise of new opportunities in America, Canada and Australia, led to the largest-scale mass emigration in history, as people were lured overseas in search of a more prosperous life. Once again Liverpool led the way, with around 200,000 emigrants a year leaving Liverpool for America. In total, it is estimated that during the 19th century around 9 million people from the UK and mainland Europe left Liverpool on emigrant ships bound for America.

In July 1850, the illustrated London News commented: “The scene in the Waterloo dock…is at all times a very busy one; with a full complement of emigrants, it is particularly exciting and interesting.”

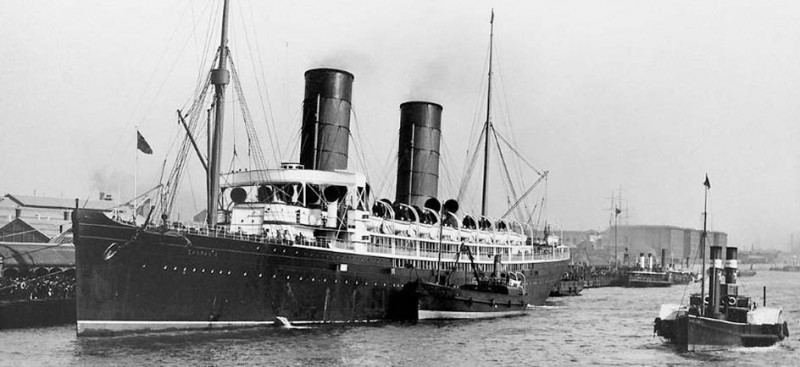

What the writer of these words probably didn’t realize was that conditions for the emigrants were not much better than those suffered by the slaves, especially as some of the earliest emigrant ships were designed for carrying cargo rather than people. One emigrant manual of 1851 recorded that passengers were “…as captive in their vessel as an African in a slave ship.” gradually, though, conditions improved, advanced engineering cut down travel times between continents, and passenger numbers steadily increased. Transatlantic emigration became another profitable trade, and there was fierce competition between shipping companies. By the beginning of the 20th century Liverpool had become the main departure port for leading liner companies such as White Star and Cunard.

Emigration levels dropped sharply when the USA introduced its restrictive immigration act of 1924, but by then overseas travel had become sufficiently pleasurable that shipping companies now began promoting the idea of travelling for its own sake. The age of pleasure cruising had begun and, as always, Liverpool was at the forefront of this new development.

Inevitably, cruise ship companies were soon vying with each other to offer the most exciting destinations, the best onboard facilities and entertainment, and even to come up with the most appealing advertisements. The competition intensified when air travel increased in popularity during the 1950s, and shipping companies had to try even harder to persuade holidaymakers to stick with cruising rather than succumb to the temptation of getting to their destination as quickly as possible by air.

Albert Dock

In 1846 Liverpool gained another commercial and architectural jewel, a closed dock with rows of warehouses constructed from brick, cast iron, sandstone and granite and featuring magnificent Doric columns along the quayside. Designed by Jesse Hartley, Liverpool’s Dock Engineer from 1824 to 1860, along similar lines to St Katherine’s Dock in London, Albert Dock was the port’s first fully enclosed dock with a system of well-ventilated, fire-proof warehouses, featuring what is believed to be the world‘s first mechanical cargo lifting and handling equipment.

The warehouses were designed to store valuable goods ‘in bond’, meaning that customs duties were only payable when goods were sold. The advantage of the Albert Dock system was that cargo could be offloaded directly into the warehouses for HM Customs to check when convenient, and meanwhile ships could be on their way within days rather than weeks. This also cut the risk of goods being stolen during the unloading process, which previously had involved unloading onto open quaysides. Another advantage of Albert dock was that it operated a one-way system to improve speed and efficiency, which again ensured that ships could achieve a much faster turnaround. Ships entered the dock at Canning Half-Tide Dock, unloaded in Albert, reloaded in Salthouse Dock and then left via Canning and Canning Half- Tide.

The first warehouses were officially opened by Prince Albert in 1846, and for the next 40 years or so Albert Dock dominated Liverpool‘s import and export business. Huge quantities of goods were imported from America, the West Indies and the Far East, ranging from rum, sugar, tea and rice to more exotic goods such as silk, ivory, spices and animal horns. Towards the end of the 19th century the oceanic trade was faltering, but trading with Europe continued until well after the death of Queen Victoria. The real downturn for Albert Dock was the decline in the use of sailing ships in favour of steam ships, which were too wide for the dock entrance. By 1920 commercial shipping had ceased at Albert Dock, although its warehouses continued to be used for storage, finally closing in 1972.

Liverpool And The Industrial Revolution

Unsurprisingly, Liverpool played a major role in the industrial revolution, importing millions of tonnes of raw materials from all over the world, transporting them to the manufacturing towns in the North West and Midlands, and then exporting the finished products. The lifting of the East India Company’s trading monopoly with the Far East in 1833 and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 further boosted Liverpool’s trading potential, allowing it to expand to all parts of the globe.

Liverpool’s single most lucrative trade at this time was cotton. Raw cotton was imported from America, India and Egypt and distributed to Lancashire’s cotton mills, with cotton goods then being returned to Liverpool for export. The trade expanded rapidly throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, with Liverpool becoming the largest cotton trader in the UK and eventually in the world. at the beginning of the 19th century Liverpool was importing over 100,000 tons of cotton a year; by the end of the century more than half a million tons were being handled annually.

More docks were needed to cope with the increased demand, the most notable addition being Manchester Dock, which was built in 1780. originally a tidal dock, which filled up at high tide but emptied out at low tide, it was converted into a permanent wet dock in 1807. its main function was to import coal from Manchester and transport imported cotton and corn to Manchester and other manufacturing towns in the north. Small boats would carry the cargo along inland waterways into Manchester Dock.

The opening of Liverpool and Manchester railway in 1810, and the Manchester Ship Canal in 1894, enabled goods to be moved in and out of Liverpool’s docks with even greater efficiency, ensuring the town’s continuing prosperity.

Decline Of The Port

At the turn of the century Liverpool continued to enjoy its status as one of the world’s leading trading ports, and had built up more than 7 miles of interconnected docks lined with warehouses, manufacturing works, ships’ suppliers, taverns and lodging houses. But the port’s fortunes were about to turn. The First World War had a devastating effect on Liverpool, with the loss of many of its workers, a considerable loss of trade and increasing competition from overseas. The Depression of the early 1930s caused further disruption, with widespread hardship.

As one of the UK’s largest ports, Liverpool was a target during the Second World War, suffering bomb attacks on the docklands in 1940 and a blitz in May 1941. Many of the allied Forces set sail from Liverpool between 1939 and 1945, and this was the landing port for over 20,000 prisoners of war. Liverpool was also instrumental in the planning and successful execution of the pivotal Battle of the Atlantic. The Waterfront now has a number of memorials to those who perished in both world wars.

Despite the bombing raids, the city emerged from the Second World War relatively unscathed compared to other parts of the UK, and soon after the war ended demand for goods began to grow. it looked as though Liverpool was well on the way to economic recovery, but the introduction of containerisation by US shipping lines in the 1950s dealt the port a hammer blow from which it never fully recovered.

From an efficiency point of view, containerisation was good news. Cargo was placed in standard-sized metal containers which could then be loaded by crane straight onto the ships, considerably reducing loading times. The problem was that it also reduced the amount of manpower needed, so thousands of dock workers in Liverpool faced redundancy. This was one of the factors that prompted the notorious dock strike of the 1990s, one of the UK’s longest-running industrial disputes.

Liverpool’s docks were unable to cope with the new containers; they were impractical for the older docks, which were also too small to accommodate the transporter ships. in 1972 the Mersey Docks and Harbour Company closed many of the older docks, most of which have now been filled in to create land for the regeneration of the Waterfront, which began in the 1980s and is likely to be ongoing for several decades to come.

The Port Today

Despite the closure of so many of its old docks, Liverpool continues to be a busy working port. A purpose-built container dock, royal Seaforth Dock, was opened in 1972 at the northern end of the Liverpool docks, and is now one of the UK’s main trading ports with North America, handling around 700,000 containers a year. it also trades in oils, timber, grain, animal feed, fruit and vegetables.

Seaforth is linked to Gladstone Dock, a former dry dock that opened in 1913 and has since been converted to a wet dock. Gladstone was an important naval base during the Second World War, but these days it is used chiefly for importing coal for processing at the nearby Hornby Dock, and exporting scrap metal to the Far East. P&O Ferries also operate passenger services to Dublin from here.

The most important new development is Liverpool2, a new container terminal adjacent to Seaforth Dock, which will be large enough for two post-Panamax vessels and is set to double the number of containers currently handled by the port. Liverpool2 is opening in the latter half of 2015.

Regeneration Of The Waterfront

Liverpool Waterfront is a triumph for the city, a major transformation of what was once a derelict area into an attractive, spacious tourist attraction, which has retained many of its historical features while boldly blending them with modern, state-of-the-art buildings.

The regeneration was spearheaded by the opening of the Maritime Museum in 1980, with the Mersey Development Corporation being set up a year later to redevelop Liverpool’s south docks. In 1983 the regeneration of Albert Dock began, and its warehouses have been converted into a mix of cafes, restaurants and independent small shops. This area also houses The Beatles Story and the internationally important Tate Liverpool art gallery, while boats from the recently-extended Leeds- Liverpool Canal are moored here.

The former Piermaster’s House, built in 1852 close to what is now the Maritime Museum, opened to the public in 1984 and recreates a typical Liverpool working class family home during the Second World War. The building is all that remains of a block of four houses, the other three having been destroyed by bombing. These houses would originally have been for a warehouse keeper and two dockmasters.

Further regeneration has seen warehouses at Prince’s, King’s and Waterloo Docks converted into apartments, and a nature reserve established in the north docks is home to variety of waders and seabirds.

In 2004 the Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City, which includes Albert Dock and Pier Head, was awarded UNESCO World Heritage Site status. a year later, the Peel Ports group bought up the Mersey Docks and Harbour Company and continued with the makeover of the waterfront.

In 2008, Peel Ports oversaw the regeneration of Mann island, the area between Alfred Dock and Pier Head, which saw some of the old docks and warehouses swept away to make room for newer buildings. The most notable of these is the Museum of Liverpool, which was built on the site of the old Manchester Dock and opened in July 2011. This extraordinary three-storey building tells the story of Liverpool and its people from the ice age to the present day.

In 2007, to mark the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade, the international Slavery Museum was opened to tell the story of the slave trade and its legacy, as well as looking at stories of modern slavery.

Liverpool one, a massive open-air retail and leisure complex, opened the following year and stands on the site of old Dock.

Further expansion of Liverpool Docks includes the proposed Liverpool Waters project, which will be one of the port’s largest redevelopment project yet. With an estimated cost of £5.5 billion, it will regenerate the derelict Central Docks area, just north of Pier Head, with the building of new apartments, offices and leisure facilities, creating around 20,000 jobs.

Liverpool may have fallen on hard times during the 20th century, but with its ability to adapt to changing needs the port seems to be well on the way to getting back on its feet. Massive investment, through projects such as Liverpool Waters and Liverpool2, means the port can face the future with renewed optimism, with the Waterfront and the working docks combining to ensure the port is a vibrant celebration of both its past and its present.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item