Imperator, Vaterland And Bismarck

The Hamburg Amerika Line (Hapag) was the greatest shipping company in the world when this trio of super liners was ordered in 1910. Albert Ballin (1859-1918) had achieved greatness for Hapag, and had shown great talent from an early age. He took over his father’s cargo and emigrant passenger business between Hamburg and New York in 1874 at the age of seventeen years. Four years later, his company handled one third of all the traffic from Germany to Liverpool and New York, the passengers originating from all over Germany and the Austro- Hungarian empire. In 1880, he began acting as the sole passenger agents for Carr Line, which was taken over by Hapag ten years later. In May 1886, under a five year contract, Albert Ballin, then aged 29 years, became the Head of the Passenger Department of Hapag and he went on to build up the company into a formidable force on the North Atlantic.

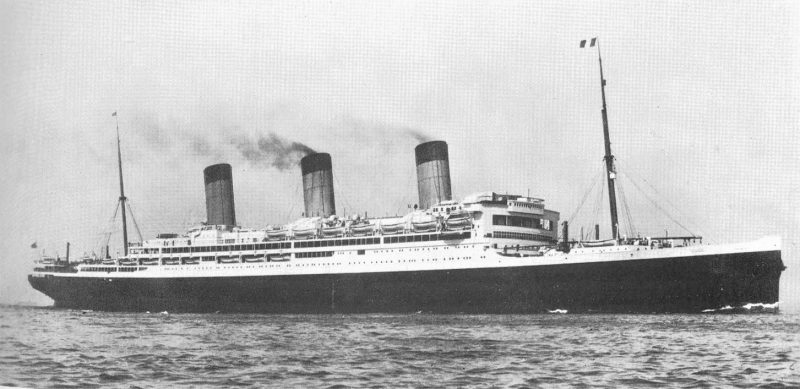

Albert Ballin was anxious to maintain the competitive balance of Hapag after White Star Line had ordered a similar three funneled ‘big three’ of the Olympic, Titanic, and Britannic, and Cunard countered by ordering the four funneled Aquitania of 44,786 grt for delivery in 1914 to run alongside the two ‘speed queens’ of Mauretania and Lusitania. The French Line chose not to compete in super liners of this size and speed, but settled for the more modest Paris of 34,569 grt and which sailed on her maiden voyage in April 1912. The keel of the first of the huge German trio was laid in June, 1910 at the Hamburg yard of Vulcan Werft as the preferred builder, Blohm & Voss of Hamburg, did not have their new long berth ready, but did build the remaining two vessels of this three ship order. She was named Europa at the keel laying ceremony but she was launched as Imperator two years later as a super liner of 52,117 grt, with Vaterland (Fatherland in German) following at 54,282 grt, and finally Bismarck at 56,551 grt.

Imperator

Imperator had an overall length of 919 feet, beam of 98 feet four inches, and depth of 57 feet one inch. She was designed with ten decks, five of these being partial decks above the weather deck (Boat Deck and Decks A to D) and five (Decks E to J) being full decks above the engine room but below the weather deck. At engine room level, there were two partial decks forward and one aft. Most of the magnificent First Class public rooms were on ‘B’ Deck including the Lounge, Library, Ritz-Carlton restaurant, and ladies’ lounge. The third funnel was a dummy acting as a ventilating shaft down to the red heat of her boilers and engine room. She had three holds for cargo and baggage, and a dozen watertight compartments controlled from the bridge to hopefully keep her afloat in the event of collision or grounding. She had transverse and longitudinal bulkheads in her engine room and coal bunker capacity of 8,500 tonnes of coal, six feet of space between her inner and outer double bottoms, with five inch thick plates forming her inner skin, and a gigantic rudder weighing in at 90 tonnes hung on five gudgeons. She had three anchors, the third being a bow anchor located in the stem, and unbelievably she was equipped with 83 lifeboats of which two were motor boats, an overreaction to the sinking of the Titanic in April 1912 just before her launching by the Kaiser himself in May 1912.

The passenger complement was 4,594 persons in four classes with a crew of 1,180 giving a total count of 5,774 souls when fully booked. First Class passengers numbered 908, with Second Class of 972, Third Class of 942, and in the bows and down in the bowels of the ship some 1,772 souls in Steerage Class, who were allowed onto the fore deck once a day to breathe some fresh air. Albert Ballin hired Charles Mewes of France and a German designer named Bischoff to help him plan the interiors of the public rooms and cabins. They were completed in a variety of traditional styles including Tudor, Edwardian, Georgian and Louis XVI. The grandeur of the First Class Dining Room, First Class Lounge and First Class Winter Garden were in stark contrast to the simple facilities in Steerage Class. The long First Class Lounges on her later sisters of Vaterland and Bismarck were cleverly designed to be pillar free by dividing the exhaust uptakes of their two functioning funnels up the side of the superstructure rather than up the middle of the ship. The uptakes came into the funnel casing at Boat Deck level, giving sloping plating upon which liferafts were placed. The Lounge comfortably seated 700 passengers and was topped by a glass dome, and had a marble bust of the Kaiser in the middle of the dark panelling at one end. The Winter Garden was very striking and featured thin pillars concealed by cane ribbing, and was decorated with full height palm trees over two decks, cane chairs and tables and at one end a huge painting of a German ‘schloss’ with an equally huge lake in front of the castle.

The First Class Dining Room was on both ‘C’ and ‘D’ decks linked by a grand central staircase, so that diners on ‘C’ deck could look down through a central balcony to those below, and the decorated domed ceiling extended to ‘B’ deck. The First Class Smoking Room was Tudor in style with dark wooden pillars, a white ceiling, and heavy ornate carving. The First Class swimming pool on ‘D’ and ‘E’ decks, at a point midway between the first and second funnels, also had a glass roof supported by sixteen Doric columns with mosaic decoration on their lower parts and was surrounded by changing cubicles, with a second storey visitor’s gallery. This pool was very similar to that of the R.A.C. Club in London, also designed by Charles Mewes and his partner Davis. First Class passengers had the use of six decks ‘midships, their promenade spaces being on ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ decks, and they had two entrances, lifts and stairs just in front of the forward and centre funnels. There were also two ultra luxurious and magnificent staterooms known as the Imperial Suites. The Second Class cabins were located aft of the third funnel up to the mainmast, while Third Class passengers were at either end of all of the decks ‘A’ to ‘D’.

The trio had buff coloured funnels and black hulls and were not designed as express liners to reclaim the Blue Riband from the Mauretania and Lusiania, but instead competed in size and grandeur of their First Class facilities with other big liners of White Star Line and Cunard Line. Nevertheless, a service speed of 23 knots was maintained by four direct acting triple expansion Parsons type steam turbines by the builder. The high pressure and intermediate pressure turbines drove the inner pair of screws, while the low pressure turbines drove the outer pair of screws to give a total of 62,000 shp. There were 46 watertube naval boilers producing steam at 235 p.s.i. pressure in no less than four boiler rooms, two serving the fore funnel and two serving the middle funnel. The four massive propellers each had a diameter of 16 feet six inches and operated at 185 revolutions per minute when at full speed. The twin engine rooms were big at 95 feet and 69 feet in length, and altogether the power output of the ‘big three’ was considerable.

Imperator sailed on her maiden voyage from Hamburg on 10th June 1913 after trials had been delayed by an explosion of benzine onboard which killed two men and injured five others, and by a grounding in the Elbe estuary at Altona on 22nd April when she came off undamaged. Her most conspicuous external feature was an incredibly large and ugly eagle figurehead perched at the top of her bow, which fortunately was removed after being damaged by a large wave on one of her Transatlantic crossings. The eagle measured ten feet in length with a 53 feet wingspan and its hideous claws gripped a cast iron globe that was bolted to a cast iron sunburst of flashing golden spikes. The Hapag motto ‘Mein Feld ist die Welt’ (My Field is the World) was written on a medal ribbon around the globe.

Imperator was immediately found to be an excessive roller, which would frighten off her important First Class passengers and ruin her financially. She was sent in the Autumn of 1913 for correction of this fault by the removal of all heavy marble baths from all of the First Class staterooms and cabins, the fitting of light deck panels and fittings instead of her heavy ones, the removal of the top nine feet of her three enormous funnels, and the pouring of two thousand tonnes of cement into her double bottom. These extreme measures corrected the rolling, and today the computer aided design of naval architecture would have prevented this top heaviness before construction started.

At New York at the end of her fifth crossing on 28th August 1913, a fire broke out while she was berthed at Hoboken. It raged for five hours with hundreds of tonnes of water pumped onboard giving her a fifteen degree list to starboard. She left New York for Cuxhaven for repairs at Hamburg without any Second Class passengers as the Second Class Dining Room had been badly damaged. After fourteen months of Transatlantic commercial service, she was about to sail from Hamburg for New York when the Imperial German Navy forbade her to sail and she was laid up at Hamburg on the outbreak of war on 4th August 1914, and she remained there for the next four years. At the end of the war, she was found by the victorious Allies to be rapidly decaying with much rusting, and she was sent to New York for a refit. At the conclusion of the refit, she went trooping between May and August 1919 and again was laid up at New York. She was then awarded to Cunard Line by the Allied War Commission in Paris for peacetime Transatlantic service in early 1920 under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, and sailed on 21st February 1920 still as Imperator from Liverpool to New York. She was then reconditioned and purchased in February 1921 and renamed Berengaria and sailed on her first voyage under Cunard ownership on 16th April 1921 from Southampton for Cherbourg and New York. She was named Berengaria after the wife of Richard the Lionheart of England.

In September 1921 she was sent to the Walker Naval Yard of Armstrong, Whitworth & Co. Ltd. on the Tyne and converted to oil fuel burning with the White patent oil burners making her more economical at 600 tonnes of oil fuel per day and dramatically reducing the number of her stokers in the engine room. This six month refit was also used to adapt her to the British standards of Cunard Line by stripping out the steerage accommodation, with metal fittings replacing all remaining heavy marble ones, and her passenger complement altered to suit American immigration quota regulations at 972 passengers in First Class, 630 in Second Class, 606 in Third Class and 515 passengers in Tourist Class. Cunard Line officials were pleased to note that she achieved 23.79 knots on one of her next crossings in 1922. She was partnered on the Atlantic in the inter-war years by Aquitania and the famous Tyne built Mauretania. In the late 1920s, much of her old Third Class accommodation was converted into Tourist Class accommodation.

Many famous people travelled on the Berengaria including the Prince of Wales, Prince George (the future King George VI), Prime Minister Ramsey MacDonald (twice), President Herbert Hoover, Hollywood film stars, millionaires, aristocrats, politicians and actors. The Christmas and New Year crossings and cruises were particularly lavish with passengers beautifully attired for dinner. Dishes on the menu included turkey, chicken, sausages, brawn, beef, lamb, veal and ham pie, Christmas pudding, fruit and custard in syrup, dates, assorted confections, savoury pastries with coffee, cheese and biscuits to follow. King George V lay dangerously ill in London just before Christmas, 1928 and his son Prince George hurried home from a posting on a Royal Navy warship in the Caribbean to New York to board Berengaria. for Southampton. He celebrated his birthday on 20th December by combining it with the ship’s orchestral concert, and auctioning off pieces of a celebratory cake for the relief fund for distressed Welsh miners.

The severe Depression years of the early 1930s saw her passenger numbers dramatically reduced, and she was sent instead on cruises from New York to Bermuda and the Caribbean, and on shorter ones to New England and the St. Lawrence. On 7th April 1931, she ran aground in thick fog on the Boulder Bank in the Solent about four miles east of the Nab Tower at the end of a crossing. Passengers were landed by tender and she refloated again the next day virtually undamaged and was able to sail on her next crossing on schedule. A year later, she grounded at Calshot Spit on 11th May 1932 while inbound from New York, but was refloated by tugs an hour later and docked undamaged at Southampton Docks. A three month refit in early 1933 gave her improved bathrooms in First Class, redecoration of the walls and furnishings in her public rooms and particularly in the Winter Garden with damask and printed linen, and seventy new cabins were installed in Tourist Class. A cinema was installed during this refit, and she sailed again on 14th April 1933 with Prime Minister Ramsey MacDonald on board again.

Berengaria was transferred to the ownership of Cunard-White Star Line on their merger in 1934, and was expected to partner Queen Mary and Aquitania from 1936 until the advent of the new Queen Elizabeth in 1940. However, things did not quite work out like that, as two fires, one during 1936 and the other in 1938 badly damaged her. The first fire in her outmoded electrical wiring systems was at Southampton and the damage was repaired, but the second at New York on 3rd March 1938 in her First Class Lounge on Upper Promenade Deck resulted in the revoking of her passenger certificate by the American authorities. It took the New York fire crews over three hours to put out the fire, with the Lounge completely gutted as well as twenty First Class Cabins on ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’ decks and the two Imperial Suites badly water damaged and with her decks badly buckled. She was sent home without passengers to Southampton, and a third damaging fire then broke out at Southampton, and Cunard Line had no option but to sell her for scrapping.

It was the compassion of one man, Sir John Jarvis the MP for Guildford and High Sheriff of Surrey, who brought both the Berengaria and the Olympic to Jarrow for scrapping. He had several shareholdings in North East Coast shipyards and industries and his plan was called the ‘Surrey Scheme’ to alleviate unemployment on Tyneside. The famous Palmers shipyard, engine works, blast furnaces and rolling mills had closed in 1933, bringing catastrophic unemployment of over 50% to this town on the banks of the Tyne. Tens of thousands of men felt bitter that no help whatsoever was forthcoming from the British Government, even though the same men walked the entire distance to London in 1936 to ask for help in the famous ‘Jarrow Crusade’. Sir John Jarvis personally paid £100,000 for the Olympic to be brought to the town in 1935, and had also bought another vessel a year earlier and brought her to Jarrow. The scrapping of the Olympic provided 18 months of work for the former Palmers workers, the benefactor had also paid half the cost of dredging the river at Jarrow from his relief fund, the other half being paid by the Tyne Improvement Commission. In November 1938 Sir John Jarvis again came to the aid of the town when he bought the Berengaria, and she arrived that month at Jarrow on the Tyne for scrapping, and had been dismantled down to the waterline by the outbreak of war in September 1939. She was left in this state during the war, and then in 1946 she was cut into two pieces and towed by Tyne tugs to Rosyth for final demolition.

Vaterland

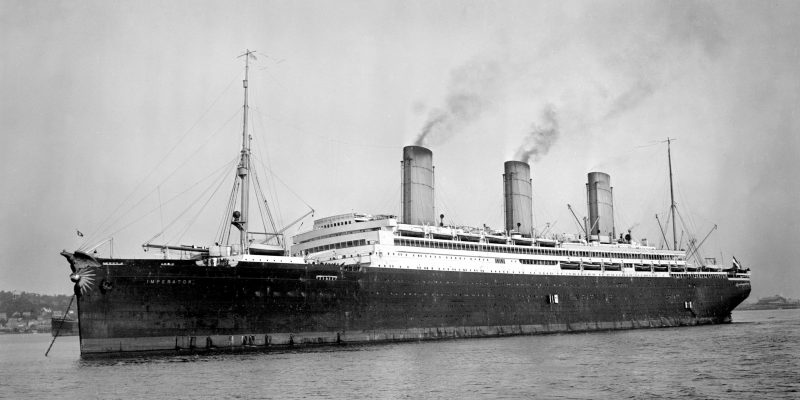

The second super liner of this German trio was launched by Prince Rupert of Bavaria on 3rd April 1913 at the Hamburg yard of Blohm & Voss. Hermann Blohm took the decision to launch the super liner after days of persistent east winds had denuded the Elbe of water, but all went well and the tugs soon had the giant liner under control. She was the second of the trio to sail out of European waters for New York and reached New York in mid May 1914. However, three months later after a very short and extraordinary German career, the advent of the Great War meant that Vaterland was interned at her Hoboken pier in New York. Albert Ballin tried several different stratagems to free her, but all were in vain. During this horrific war, the German fleet was virtually obliterated and the Hamburg Amerika Line was left at the end of 1918 with only some of its shore staff and the old four funnelled record breaker Deutschland built in 1900. She was overhauled and had her funnels reduced to only two and was renamed Hansa with accommodation for 36 in First Class and 1,350 passengers in Third Class. A running mate was required and Hapag came to an agreement with a newly formed Harriman concern in 1920, United States Lines, to operate a joint service between Hamburg and New York, each company retaining its independence however.

The crew of Vaterland had been rounded up and taken to Ellis Island and given the option of becoming American citizens when Vaterland was seized by the American Government on 6th April 1917 on their entry into the war. She was converted into the troopship USS Vaterland with Capt. Joseph Wallace Oman in command. A great deal of engine repairs was then necessary as her German crew had sabotaged them during her long stay in New York. She was renamed USS Leviathan by President Woodrow Wilson on 6th September 1917 and sailed on 17th November 1917 on a trial trooping voyage to Cuba. She reported for duty on her return with the Cruiser and Transport Force, and in December 1917 made her first trooping voyage to Liverpool with fourteen thousand troops. She was painted in the British ‘dazzle camouflage’ in March 1918, a scheme she carried for the rest of the war. She carried some 119,000 troops across the Atlantic to Brest to defeat the armed forces of the nation of her builders.

She then reversed the flow of troops carrying the survivors back to the United States with nine westward crossings ending on 8th September 1919 at New York. She was decommissioned on 29th October 1919 and laid up at Hoboken until her future employment could be worked out. New blueprints had to be made as none were forthcoming from Germany under the Treaty of Versailles. She was the subject of an agreement by the International Mercantile Marine (I.M.M.) on 17th December 1919 under which they agreed to maintain the vessel until a final decision could be made. She later began a fourteen month $8M refit at Newport News in February, 1922 to equip her as the premier Transatlantic liner of the United States Lines (Shipping Board) fleet. She was converted to oil fuel burning, and all of her wiring, pumbing and interior layouts were stripped and redesigned.

New interior decorations and furnishings were designed by New York architects Walker & Gillette, but retained part of her former Edwardian, Georgian, and Louis XVI styles with modern additions such as the original Verandah Café being replaced by an Art Deco night club. The First Class Dining Room was renamed the Ritz-Carlton and maintained its previous high standards. The noted naval architect William Francis Gibbs, who became part of the famous maritime designers Gibbs & Cox of New York in 1929, had recreated the blueprints of the vessel, and had created virtually a completely new super liner, with an average of 27.48 knots now obtained on speed trials from hull and engine modifications. She became the world’s largest and fastest Transatlantic liner until the advent of the three funneled Normandie of French Line in 1935. Mr. Gibbs was also given the unusual and unenviable task, as a professional naval architect, of actually operating the rebuilt liner on her first six crossings as an American liner.

She now carried 970 passengers in First Class, 542 in Second Class, and 944 in Third Class, with 935 Steerage Class in the bows and bowels of the ship with a first sailing on 4th July 1923. She ran under the name of Leviathan with her three funnels painted a colourful red, white and blue for the next ten years until withdrawn in June 1933 due to the effects of the Great Depression and her high crew and fuel costs. She had also run ‘booze cruises’ in 1929 to try and make money after American regulations were relaxed to allow her to sell ‘medicinal alcohol’. She was reactivated in June 1934 for a series of five round voyages from New York to Le Havre and Southampton in the summer of 1934, but then was laid up again. She was the largest liner at 59,956 grt ever to fly the ‘Stars and Stripes’ of the United States of America, but no further voyages were undertaken after 1934. The I.M.M. paid the American Government half a million dollars for permission to retire her while keeping her in running order until 1936. She made her final 301st Transatlantic voyage to the scrappers yard at Rosyth, arriving on 14th February 1938 for demolition by Thomas W. Ward. She had only lasted 24 years, whereas the lead super liner, Imperator, had lasted 33 years but the last seven of these had been in a cut down condition on the Tyne during the war years.

Leviathan as well as being the largest ever American liner is also remembered for experiments with a special aircraft catapult temporarily erected just aft of her wheelhouse in order to fly the aircraft ashore with important mail as she neared port, and the first television experiments aboard ship, the first symphony concert broadcast at sea, and use of the first ship to shore radio telephone. The ship’s orchestra under the direction of leader Nelson Maples was very well regarded, and several gramophone records were produced by Victor Records of this orchestra during the inter-war years. Unfortunately, Leviathan is also remembered for having lost a great deal of money while operating at less than half full across the Atlantic, in fact the vessel never made a dollar of profit during its career, each voyage making a loss on average of $80,000. The managers of United States Lines lamented ‘Aquitania with her liquor licence was the most popular ship on the Atlantic, and it cost us nine million dollars to find out!’

Bismarck

Bismarck was launched by the Kaiser himself at Hamburg on 20th June 1914 after Countess Hanna von Bismarck, the intended sponsor and grand-daughter of the German Iron Chancellor who had died in 1898, had failed to smash the launching champagne bottle, and the Kaiser, standing nearby, stepped forward and did the honours himself. The giant liner was destined never to sail the Atlantic as a German vessel as she lay incomplete at the yard of her builders for the duration of the war. Albert Ballin committed suicide in 1918 one day before the end of the war, the Kaiser was sent into exile, and the giant liner was ceded to Britain on 28th June 1919 as war reparations. She was completed at the yard of her builders under British supervision by Harland & Wolff Ltd. and despite a serious fire caused deliberately by the German shipyard workers. The latter were reluctant to hand her over to a British company, having deliberately painted her name as Bismarck and her funnels in Hamburg Amerika Line colours. She was finally completed on 28th March 1922 almost eight years after her launch, and sailed to Liverpool as a war replacement for the lost Britannic. She was purchased with Berengaria ex Imperator on a joint basis by a Cunard Line and White Star Line consortium to avoid overbidding between the British companies, this joint ownership continued until 1932. Bismarck began Transatlantic service flying the Red Duster under the name of Majestic for White Star Line on 10th May 1923 from Southampton to Cherbourg and New York under the command of White Star Commodore Sir Bertram Hayes.

During Cowes Week in August 1923, the ship received a great honour by being inspected by King George V and Queen Mary. The Royal couple toured all of the ship, with First Class passengers located ‘midships over six decks, while Second Class were located aft of the third funnel to the mainmast. Majestic was longer than her two previous near sisters, and her Second Class accommodation was slightly longer than in the previous pair. The trio were never true sisters as their length and beam varied, Vaterland was 950 x 100 feet and Bismarck was 956 x 100 feet in length and beam. Third Class accommodation was at either end of all of the Decks ‘A’ to ‘D’, and her Promenade Deck was open along its full length. She suffered a crack in her hull ‘midships in 1924, resulting in the plating being strengthened on long stretches on both sides to solve the problem, however her hull remained slightly suspect until the end of her days. She made her fastest crossing in 1925 in five days and averaged 25 knots.

She was the premier White Star Line vessel along with the four funnelled Olympic and the smaller Homeric on the Southampton to New York express run. In 1928, she was refitted and reboilered at Boston Navy Dockyard then completed at Southampton. There was no graving dock in Britain big enough, thus a floating dock at Southampton soon followed then the big King George V dry dock at the top of the New Docks. In 1930, the black of her hull was raised so that the white strake line was removed. During the Depression, she and Olympic were sent on occasional cruises from New York to Bermuda and the Caribbean, as well as the three and one half day ‘booze cruises to nowhere’ and to Halifax in Nova Scotia in summer during their seven day stopovers in New York. She was transferred in the merger with Cunard Line to the newly created Cunard White Star Line in February 1934, replacing the famous Tyne built Mauretania. In October 1934, a massive Atlantic wave smashed her bridge windows injuring the First Officer and White Star Line’s final Commodore Edgar J. Trant, who was in hospital for a month and never sailed again. She made her final 207th voyage across the Atlantic to New York in late February 1936 and was replaced by the new Queen Mary to operate the Cunard/White Star service on the Atlantic.

She was then sold in May 1936 to British shipbreakers and then promptly sold on two months later to the British Admiralty for conversion at a cost of £472,000 by the Thorneycroft yard at Southampton into a training ship for two thousand boys at Rosyth. She was renamed Caledonia with her lifeboats removed and her masts shortened and her funnels cut down by the width of the black band at the top in order to pass under the Forth Bridge. She was fitted with seven guns plus rangefinding control systems. All of her machinery was left intact and she was connected to the shore by pipe for sewage disposal. She arrived at Rosyth on 10th April 1937 with eight tugs taking her to her berth and she was commissioned thirteen days later. On the outbreak of war, all of her cadets were removed to shore accommodation as her berth was required for naval use. She was anchored in the Firth of Forth within Rosyth Base limits.

She would have been converted back into a troopship at the end of 1939 if Admiralty plans had come to fruition, however a serious fire at Rosyth on 29th September 1939 halted this conversion. She sank in shallow water on an even keel at her moorings and most of her wreckage was scrapped on the spot after salvage in March 1940. A few remaining pieces were raised in July 1943 and towed to Inverkeithing for final demolition. Thus, the third and last of the ‘Big Three’ German super liners had the shortest career of all, a mere fourteen years on the Atlantic followed by a further three years as a training ship at Rosyth. In this respect, the first of the trio, Imperator later renamed Berengaria of Cunard Line was the most successful of the trio. It was pleasing for New Yorkers to often see the three former German giant liners on the same day at different piers between 1923 and 1936 as Majestic ex Bismarck, Leviathan ex Vaterland and Berengaria ex Imperator either having just finished or about to start another Transatlantic crossing.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item