By Serena Shores

It was a chance natural occurrence which allowed a small settlement called Boston near the bottom left-hand corner of the square-sided estuary known as The Wash (sandwiched between the counties of Norfolk and Lincolnshire) to grow into a bustling port.

In the early Middle Ages, Boston (no more than a quarter of the nearby settlement of Skirbeck), had developed at the head of the Haven, a tidal inlet of the Wash into which flowed a stream carrying water from the vast tracts of virtually untamed fenland to the east and west. The reason for this situation appears to be that the site was where the navigable tidal waters lay alongside the land route using a terminal moraine ridge.

The River Witham, however, (on which the town is now built) followed quite a different course, flowing into the Wash further south than it is today, near the Welland Estuary at a place known as Bicker Haven. At this point, the predecessor to Boston, a port called Drayton had established where the Witham emerged, taking advantage of the valuable trade route following the river as far as the city of Lincoln 35 miles north west, where it joined a cut constructed by the Romans know as the Fossdyke, linking Lincoln to the River Trent at Torksey and giving access to the Humber.

However it was a dramatic flood in the September of 1014 which permanently altered the geography of the area, diverting the river Witham so that it now linked up with the Haven.

Business was soon moved from the now abandoned town of Drayton and Boston became established as a port in its own right.

During the eleventh and twelfth centuries Boston soon grew into a prosperous town and port, notable by the fact that its contribution to the quinzieme duty (raised on the fifteenth part of the value of merchants’ moveable goods) being, in 1204 only £56 behind London, which paid £780. Standing testament to this great commercial activity and the wealth of the town is St Botolphs, the largest parish church in England, with its massive, incomplete tower known as the “Stump.”

Being one of the official “Staple Towns” of England, authorised to carry out the import and export trade, international trade increased dramatically during this period and Boston (like its neighbour King’s Lynn on the other side of the Wash) soon joined the Hanseatic League, who built a local depot, exporting a third of all the wool to leave England, salt and grain produced locally and lead brought from Derbyshire via Lincoln. The main import was wine, fine cloth, furs, leather and spices, along with timber and fish from Scandinavia. Surrounding villages became heavily reliant on the new town and a fair held at Boston once a year attracted merchants from all over the Continent.

Unfortunately, even though the town received its charter in 1545, the boom period was over and the port had already begun to decline for two specific reasons. The first was the way the nature of the wool trade altered significantly during the fifteenth century and the second, a problem which had blighted the port almost from its humble beginnings and that was the issue of silting of the river Witham, the Haven and also the Fossdyke, the essential connection to the Midlands.

With the shift of the wool industry from the Midlands to other parts of England and the move from wool production to the more lucrative weaving, Boston soon found itself with a dwindling volume of exports and was dealt an almost deadly blow when the Hansa merchants left the town, leaving coastal trade about the only surviving activity. This of course was further threatened by the silting, which had for some time been seriously hindering shipping.

From as early as 1142, various forms of sluices had been constructed below Boston, including a sluice built in 1500 (by which time the wool trade had all but disappeared), but navigation through the Haven and in the river itself continued to deteriorate, so that by the mid-1800s, few vessels could reach Boston.

It wasn’t until a “Grand Sluice” was proposed in the middle of the 1700s and constructed in 1766, that a viable solution to the silting of the Haven was found. The sluice, built on a two-mile cut extending the channel further into Boston, maintained river levels behind it up the Witham, kept the tide out of the Fens and helped scour the channel below it. It consisted of three channels, each 17’ (5.2m) wide fitted with pointed gates on both sides and a lock adjacent to the north bank of the river which could be used as further flood relief if required.

Although originally very small, it was lengthened to its current 41’ x 12’ (12.5 x 3.7m) in 1881. The pointed doors on the non-tidal side were replaced by guillotine gates in 1979.

By coincidence, this construction of the sluice coincided with an act in 1762 endorsed by the Witham Navigation Commissioners and the Witham Drainage General Commissioners creating an ambitious network of navigable drains (known as the Witham Navigable Drains) to dry out parts of the vast area of fenland in Lincolnshire, including Holland Fen to the west of Boston. This, for the first time created farming land in the area, which proved to be very fertile and started producing significant amounts of grain which increased traffic in Boston significantly as the cargo was shipped round the coast to London. The town became a wealthy boom town by 1800 as more and more fenland was reclaimed and used for crop production.

Unfortunately, although benefitting the Haven, by the turn of the 18th century, it became very clear that the sluice was actually creating a silting problem in the river above it. Considerable works were carried out to improve the river and its locks constructed at the same time as the sluice. Also, by increasing the clearance under a medieval bridge in Lincoln, soon the traffic of sailing vessels and barges was joined by a steam packet. This didn’t last very long however, because the railways reached Lincoln in 1848, the Great North Railway taking over the Witham and Fossdyke navigations and building a line from Boston along the eastern bank of the river.

What followed was a determined effort to take trade away from the river and by the 1860s, freight traffic had declined, the volume of coal passing through the Grand Sluice dropping dramatically from 19,535 tons in 1847, to a mere 3,780 tons in 1857. Although the railway company was obliged to maintain the river, by 1905 total traffic had fallen to 18,548 tons, consisting of general merchandise and agricultural produce. Boston had eventually become a busy railway hub, moving local produce and trade from the docks. But this too became much quieter though by the 1960s.

In 1884, Boston was given a significant commercial boost by the moving of the Port from along the Haven to a new site to the south of the town, an area now known as Haven Wharf, (where the river bends to the east and broadens out). This allowed the building of new wharves and enclosed docks of a modern type capable of dealing with large ships, with suitable warehousing and rail access. A new cut two miles long was made to the Wash and was largely responsible for an expansion of the town’s maritime trade and deep sea fishing. The first ship to pass through the 300ft lock and berth in the six-and-three-quarter acre dock did so on the 15th December 1884.

Boston once again became an important centre for foreign traffic, exporting grain and fertiliser and importing timber. Indeed the notable increase in trade can be seen in the number of vessels entering the dock, which numbered 605 in 1894, compared to only 396 in 1881. The fact that the river Slea was made navigable from Sleaford to the Witham also increased the amount of traffic travelling through Boston.

The Boston Dock Company was dominant at this time and many trawlers started to come to Boston for the Boston Fishing Company (whose boats were named after villages around Boston) and the new Steam Trawlers Company. There were also ice boats such as the Starbeam bringing block ice from Norway. A short lull occurred when the fishing activities were moved away in the period between the two wars, and in the First World War, for instance, the port was used by hospital ships.

The 20th century saw the port continue to expand, handling grain, fertiliser and animal feed, sugar beet, wheat and potatoes. During the ‘20s the port was visited by vessels such as the Fossdyke, bringing in fish and taking coal on her outward journey, the Bostonian, again carrying fish, then coal, and the English Rose, entering light and taking coal out.

The War years saw the construction of a massive steel-framed, concrete-clad silo and in 1949 came the Black Sluice (extended in 1966), a pumping station controlling the waters of the South Forty Foot Drain which runs between Boston to Guthrum Gowt near Spalding, a considerable way to the south.

The Port also underwent significant changes from the 1960s onwards. Having been under public ownership since Atlee’s nationalisation in 1947, the port remained under municipal ownership until the Port of Boston Limited Company was formed and it finally came under private ownership in 1989. It closed to the public from 1990 and warehouses from the 19th century were demolished and replaced by modern sheds and open quaysides. The port expanded in area to take in the public park and much of the railway infrastructure, which had been depleted since the 1970s, was furthermore abandoned in favour of road transportation, (although a swing bridge over the Haven is still in use for daily freight trains).

During the 1980s, vessels such as the Northumbrian Lass (captained by an R. Sorsen) were bringing steel from Antwerp along with the Sea Odin (captained by M. Jansen and travelling from Duisburg) and the Judert (Captain Pledge) bringing soya beans from Rotterdam. Vessels departing the port included the Lys Borg (visiting for Lys Line) heading to Oslo under Captain Ronning, carrying a general cargo and the Solar (under R. Steffens) destined for Vargom with the same.

In 1979 and 1980, the port’s traffic topped 900,000 tonnes and 1,000,000 tonnes respectively for the first time. In 1979, the probable operating revenue for the dock was put at £957,311 and this comprised of dues on ships at £160,908, dues on goods of £239,472, cargo handling, £264,404, cranes and plant, £194, 456, warehousing and storage, £17,065, and locking, boating and mooring, £20, 450.

However these apparently healthy figures were put in better perspective by extensive outgoing costs, meaning probable expenditure was put at £794, 846. These included expenses such as £80,000 for lock pit wall repairs, £56,250 for general maintenance and repairs and £74,433 for dredging, bringing the real probable operating surplus to a rather modest £24,885.

The following year was even more disappointing with an anticipated surplus of £60,000 turning out to be no more than a tiny £7,391. The reason for this was partly because of the disastrous steel strike accounting for a third of the 1,000,000 tonnes and costs going way over budget (the dock wall repairs eventually came in at £130,000). There were also issues about the high cost of sending locally-grown grain through Boston, with many thousands of tonnes of it being exported through Gunness near Scunthorpe instead. There were even whispers about the possibility of closure.

Some good news for the port during this period however, came with the arrival of Norwegian Lys-Line, who began operating out of Boston in 1981. The company would stay with the port for a further 20 years, until moving to Immingham for the simple (rather sad) reason that their new generation of ships were just too large to enter the dock.

Departing from Boston Dock in the 1990s were the Nora (captained by Lauwe) destined for Amsterdam with a cargo of rape seed, the Wilhelmena-V (under Smidt), heading to Antwerp with the same and the Victory (Captained by De Boom) taking barley to Rotterdam. In 1994, the number of cargo vessels visiting the port was 703.

More recent arrivals and departures dating from 2000 include the Njord (under Captain Touwslager) carrying steel from Liege, the Hoomos (under Captain Osterman) bringing steel from Ghent and the Linda Buck (under Ivanewko) destined for Rotterdam with containers. To the present day, these arrivals also include the Sea Riss, Boston’s most frequent visitor, making 81 visits in 2014 bringing steel in from Dunkirk and one of the longest ships to visit, the Sormvoskiy 3064 at 119.2m. The Raba, RMS Wedau, Sea Harmony and Swanland can also be seen in the dock.

Owned by Victoria Group since 2004, the Port of Boston handled 824,000 tonnes in 2014.

The figure for that year is made up of domestic traffic (2,000 tonnes inwards and 31 outwards) and foreign traffic showing imports of 666,000 tonnes and exports of 82. The cargos are made up of ores, agricultural products, dry bulk, forestry products, general cargo and iron and steel.

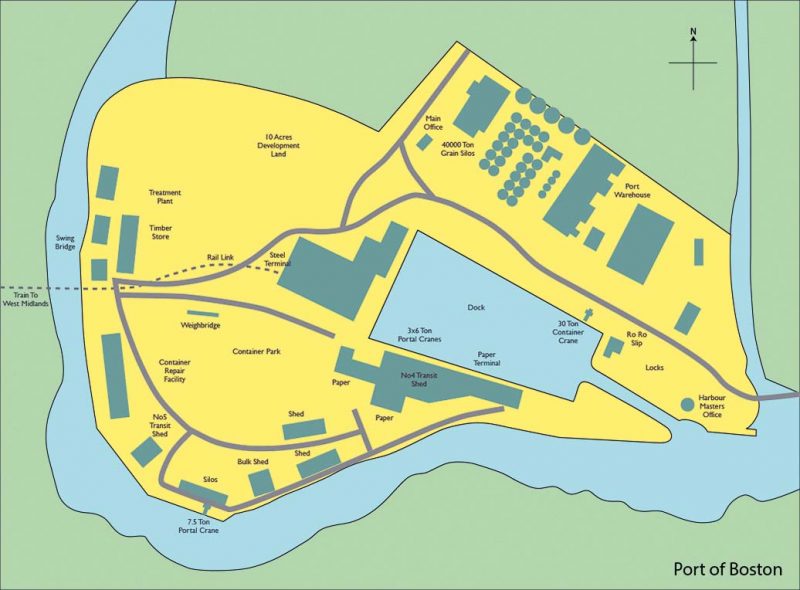

The port is positioned as a link between the Industrial Midlands and North of the UK and very handy for the near Continent and Scandinavia. It sits on the major trunk road connections of the A16 and A52 which pass right by the dock and covers 246 square kilometres of the Wash, with 31 buoys being maintained to mark the approach channels and 32 lighted beacons allowing safe traffic for commercial shipping on all tides.

The dock has an observance of 95m with a cill clearance of 1.5m, with a length limit of 80m at Riverside Quays (although these limits can be exceeded for certain vessels, including those of up to 120m and with a clearance of only 1m). It can accommodate 11 vessels at a time at its 650m of quay frontage and 700m of riverside berths are serviced by 18,000m2 of warehouse storage. There is 45,000 tonnes of grain that can be stored in the silos at the dock and a smaller silo is available on the river berth. The port also has a container park although at present this is used for general cargo.

Boston has 10 shore side cranes running from 6 to 50 tonnes capacity, a fleet of forklift trucks, tugmasters, shunt vehicles and associated cargo handling equipment. The port also owns its own railway engine which it uses to move steel from the dock to the railway sidings, where it is collected and taken to customers.

A future Environment Agency scheme creating a flood barrier for the town will alter berthing arrangements at the port, but will not be detrimental to working operations or cargo throughput. As part of the Fens Waterway Link which has already seen the building of a new lock between the South Forty Foot Drain and the Witham at Black Sluice, it could potentially become a hub for waterway leisure traffic.

Over the year the port has seen changes in trade and a reduction in the number of vessels, but due to the increased size of vessels, the overall tonnage remains high and profitability is such that the Port can continue to upgrade its equipment and infrastructure as required to meet current demands. Overseas trading patterns and the port of origin of import cargoes ensure that vessels’ size are suitable for the Port and there is no reason to believe this will alter in the foreseeable future. The Port is in a strong position and with its own stevedoring, forwarding, transport and agency departments, can handle enquiries of any nature.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item