FOUNDER OF THE ORIENT OVERSEAS LINE

“The whole thing seems like a mad fantasy”, commented that doyen of British travel broadcasters Alan Whicker in November 1971.

Within two months the object of that fantasy, the largest passenger ship in the world, would be destroyed by fire in circumstances that remain a mystery. The vessel’s owner, who presided over the largest independent shipping conglomerate on the planet, was half a world away in France attending the launch of yet another new ship. When he was informed of the tragedy C.Y. Tung wept.

The ’Onassis of the East’ (a misnomer as we shall discover), was born on 28th September 1912 at Dinghai on Zhoushan Island, across the bay south from Shanghai. Chao-Yung, prophetically meaning ’heralding fame and prosperity’, was the third of five children, whose strictly disciplinarian and ambitious parents provided him and his siblings with a classical Chinese education.

Ill health significantly disrupted Chao-Yung Tung’s schooling but it didn‘t appear to hold him back. Quite apart from any parental pressures, he was a highly motivated and dedicated student, with a natural propensity for figures and an exceptional memory, who read avidly but also learnt from observation and experience. He reputedly told his parents that despite missing large swathes of school time he was always ahead of his teachers and classmates anyway. Certainly, he never lost this appetite or capacity for attaining knowledge.

Tung’s father S.C. Tung was a merchant who ran a printing shop and later a hardware store. He died in 1932 when Chao-Yung was barely twenty. By then he had adopted another name, Hao-Yun meaning ’majestic cloud’, which reflected his shift to a more idealistic, spiritualist outlook. The death of the father brought mother and son even closer together and she would remain a cornerstone of her son’s life until her own death at the age of 99 in 1981.

Understanding something of Chinese politics and Shanghai society in the 1920s and 1930s is helpful to comprehending the multiple influences on Chao-Yung Tung in these formative years and his conflicting loyalties in later life.

The city in which he grew up was a prosperous cultural melting pot, where the Shanghailanders (European and American communities) predominated, as they had since taking a foothold through the Treaty of Nanking in 1842. Perhaps inevitably with the resulting wealth concentrated in the hands of so few (Shanghailanders constituted less than 2% of the city’s 3 million inhabitants) the majority Chinese population became progressively more assertive. The city was a hotbed of political volatility where organised crime was also endemic. Ever since the 1911 revolution that replaced the Qing dynasty with a republic ultimately governed by Chang Kai-shek’s nationalist Kuomintang party, traditional Chinese social structures had been challenged.

The violent suppression of Chinese Communist Party activists in the 12th April Incident of 1927 was typical of the ensuing power struggle which culminated in Civil War. The Communists eventually prevailed on the mainland in May 1949 creating the People’s Republic of China, whilst Chang Kai-shek’s Republic of China took refuge on the island province of Taiwan. Like many in Shanghai’s Chinese business community, C.Y. Tung had a close affinity with the Nationalists and had worked directly for the government. Consequently, although passionately Chinese he was forced into exile and together with many contemporaries moved his operations to Taiwan and ultimately Hong Kong.

These events lay far into the future when seventeen year old Hao-Yun secured employment with the Kokusai Transport Company, a Japanese firm based in Shanghai. The following year, 1930, he took a job at the Tientsin Navigation Company in that northern city, now Tianjin, a role and company that would in many respects shape his life.

Despite a natural reserve Tung’s hard work, energy, enthusiasm and insight made him stand out. He may have been shy, but C.Y., as he was affectionately and almost universally known, was an outspoken critic of the local economic and social system that conferred special privileges on Shanghai’s European Concessionaires. Perhaps because of growing up in such a cosmopolitan but socially divisive atmosphere Tung became an impassioned supporter of Chinese causes, yet paradoxically taught himself English to broaden both his business opportunities and circle of friends. His exceptional negotiating and diplomatic skills came to the fore, manifesting in the resolution of a disagreement between local and foreign lighter operators and his key role in moving the company’s office to the British Concession in Shanghai. By the age of 23 he was already Vice President of the Tientsin Shipowners Association.

C.Y. Tung’s personal life was also going through an important transition at this time and the two (business and private) overlapped in 1933 when he married Koo Lee-ching. She was the daughter of C.S. Koo, a prominent Shanghai shipowner and founder of the Valles Steamship Company.

Shortly thereafter he went on a three month long Buddhist retreat at Hangchow. This period had a profound impact on him, and as a result meditation became a daily ritual (he was also an inveterate diarist), with the resultant peaceful contemplation a key source of physical and mental strength throughout the rest of his life.

That inner strength manifested in a profound belief that he could help the indigenous Chinese transportation system, particularly shipping, grow. C.Y. Tung gained further prominence for his role in a government sponsored rescue mission for icebound ships at Po Hai Bay in northeastern China during the frigid winter of 1936. With supplies running low he helped co-ordinate the Tientsin Navigation Company vessels and Ministry of Transport aircraft that brought much needed provisions to the marooned fleet in early February.

Doubtless on the back of this involvement he was commissioned by transport minister Yu to devise a plan that would revitalize the beleaguered Chinese shipping industry, which was suffering from diminished investment, as a legacy of the Great Depression, and international competition. Tung’s proposals emphasised the need for state subsidies to bolster investment in both the coastal and deep water sectors. Perhaps he already suspected being a recipient one day.

Long term planning was almost impossible in that decade of turmoil and the following year simmering Japanese imperial ambitions and regional skirmishes erupted into full-blown conflict.

The Second Sino-Japanese War from July 1937 to September 1945 included the particularly brutal ‘Battle of Shanghai’ in which the invaders ultimately prevailed despite brave resistance from the National Revolutionary Army. C.Y. Tung and his associates were forced to decamp to the relative safety of Hong Kong.

Given the colony’s later significance it seems appropriate that Tung’s first tentative forays into running his own shipping agency were taken in Hong Kong in March 1941, where he established an agency to handle British and Panamanian flagged vessels operating in Chinese waters.

Within a year, post Pearl Harbour, the Japanese invaded Hong Kong and Tung’s Chinese Maritime Trust (1941) Ltd. was forced to close down its offices in the British territory, re-establishing them later at Chungking (Chongqing), China’s provisional wartime capital.

Like Chang Kai-shek’s government, many businesses and heavy industries relocated to the city from southern and eastern China during these years. Although hundreds of miles from the sea it was an important inland port on the Yangtse River. Here C.Y. Tung and fellow shipowners and agents planned the redevelopment of the nation’s shipping industry in the post-war era.

![]()

![]() The end of the war in 1945 heralded both opportunity and austerity, with the resilience engendered during the years of struggle reaffirming C.Y. Tung’s determination that China should play a prominent role in post-war international shipping.

The end of the war in 1945 heralded both opportunity and austerity, with the resilience engendered during the years of struggle reaffirming C.Y. Tung’s determination that China should play a prominent role in post-war international shipping.

He envisaged a native fleet, owned, crewed and operated by Chinese and lobbied unsuccessfully for the acquisition of captured Japanese tonnage in compensation for Chinese wartime losses.

Nevertheless, the government did agree to compensate shipowners for vessels that had been commandeered during the war and when the US Congress agreed to sell some of the newly surplus Liberty and Victory ships, several were acquired under a pooled arrangement called China Union Lines.

The joint venture was short lived. Perhaps inevitably disagreements arose amongst the shipowners involved but C.Y. Tung had already formed a new China Maritime Trust Ltd. (minus the year 1941), based in the famous International Settlement at 12 The Bund, Shanghai. It was handily placed for the major financial institutions required to capitalise his new venture.

He remained determined to achieve his goal of a powerful indigenous Chinese fleet but faced huge economic and logistical difficulties in the war ravaged country.

He had to contend with spiralling inflation, political instability and a lack of the necessary skilled labour.

A huge step came when C.Y. Tung negotiated a charter deal with the Belgian Economic Delegation based in the US for the transport of coal products from Europe to the USA. Most of the requisite veteran ships were acquired by China Maritime Trust from Moller and Co., an operator handily based in Shanghai where the Swedish founder, Captain Nils Moller, had started the business in 1882. Several of the vessels were over 30 years old and most were of 4,000-5,000grt.

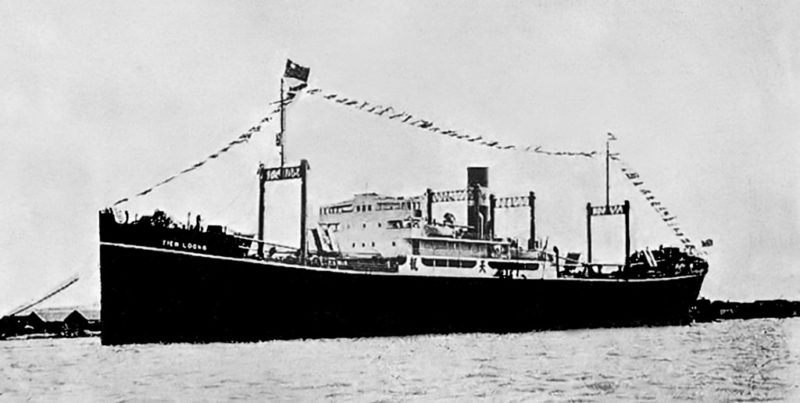

Fittingly perhaps given her namesake’s pioneering spirit it was the 6,907grt former Nils Moller, renamed Tien Loong, that left Shanghai on the first such voyage bound for Le Havre on 8th September 1947.

It was a newsworthy event covered by both French and Chinese newspapers when she arrived, flag bedecked, in the Normandy port on 29th October.

Having loaded her cargo in Antwerp she then crossed to Norfolk Virginia, making history and more newsprint coverage by being the first Chinese financed, owned, managed and crewed steamship to have crossed the Atlantic Ocean.

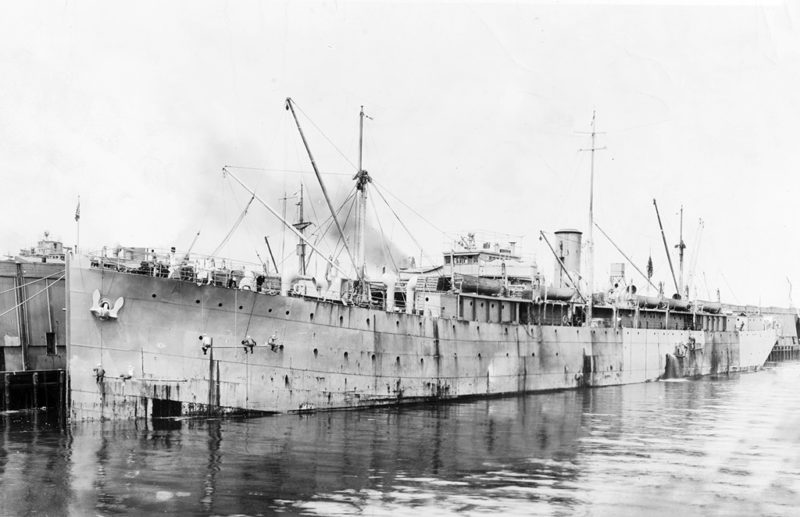

This would prove to be the first of numerous milestones for C.Y. Tung’s business evolution. The following year on 25th February 1948 the 450 ft long, 7,470grt Tung Ping, originally USS Radnor and purchased from Luckenbach SSC for whom she sailed as Jacob Luckenbach, made the company’s first trans-Pacific crossing from Shanghai to San Francisco.

She was the largest vessel in the Chinese merchant marine and subsequently sailed to Colombia and Venezuela with Filipino copra, going on to New Orleans to load further cargo.

By the end of 1948 C.Y. Tung’s China Maritime Trust owned and operated nine vessels with a total gross tonnage of approximately 40,000. Each sported a predominantly black funnel but with a pale band on which was painted a single plum blossom, a potent eastern oriental symbol of perseverance, resilience and regeneration as well as prosperity, purity and good fortune. The flowers are also associated with beauty although it is a matter of conjecture if this could be applied to Tung Ping and those early fleet mates.

It is important to place these events in context. When Tien Loong arrived in Le Havre C.Y. Tung was less than 35 years old, he was building a fleet against the backdrop of economic austerity in a country that was enveloped in a bitter civil war that would end in 1949 with the incumbent Nationalist Government, whom Tung supported, defeated on the mainland and exiled to the island province of Taiwan.

C.Y. Tung was also forced to leave his native Shanghai forever, following Chang Kai-shek across the Taiwan Straits before setting up operations once more in Hong Kong.

Direct comparisons between Tung and his famous contemporary Onassis, who was six years his senior, are tempting though generally misleading. There is some commonality, both founded their businesses in the immediate post-war era utilising second-hand tonnage and making the most of the regulatory and taxation benefits conferred by the ‘flags of convenience’ authorities of Panama and Liberia. Oil tankers were the cornerstone of both empires.

It was in their ethos, manner and lifestyles that the two diverged. Where Onassis always operated on the fringes of legal and ethical limits, seemingly ambivalent of his ships and crew welfare, regarding them purely as profit making commodities, C.Y. Tung appeared to invest as much emotionally as financially in them.

His goal was to promote national as much as selfish interests and as such he insisted on a Chinese crew, with Taiwanese officers after 1949. His enthusiasm for his ships was palpable and in later years he purchased superannuated liners like others might collect stamps or models.

Onassis and Tung were extremely wealthy men but in contrast to the Greek’s flamboyance, the affairs, superyachts and playboy lifestyle, C.Y. Tung lived relatively modestly.

Despite being a self-confessed workaholic C.Y. Tung was a devoted family man and tried to maximise time with his wife and five children (three daughter’s Alice, Shirley and Mary and two sons, Chee-Hwa and Chee-Chen). His greatest extravagance was real estate and whilst he may not have owned his own island, as Onassis had Skorpios, he owned properties worldwide, ultimately including the impressive Red Bank villa in New Jersey, and a beautiful lakeside property at the Japanese resort of Nikko.

His New York apartment overlooked Washington Square and the one in London was ideal for strolls in Regent’s Park.

Nevertheless, his true indulgence was the Island Club, the family home in Hong Kong originally built in the 1930s as Fairhaven for the businessman Tang King Po. C.Y. Tung acquired it in the 1950s and duly lavished time and money on upgrading the house and gardens, including a swimming pool and an extravagant pavilion which he designed himself, with views out over the South China Sea. It was both a retreat and a place to lavishly entertain his many friends.

Tung was a great patron of the arts. He sat on the board of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Society and was involved with various Ballet and Opera groups.

Indeed, C.Y. Tung was a true polymath, with interests spanning a broad spectrum of artistic, educational and scientific endeavours. He befriended US Presidents as diverse as Carter and Reagan, and politicians (not always perhaps the most desirable characters!) and celebrities from across the globe, in his calm, quiet and rather intense manner.

Nevertheless, ships were and would remain his greatest passion. By necessity the original fleet was a mishmash of second-hand tonnage but often with innovative conversions for specific roles.

Amongst the first of these were a pair of former second world war T-2 US naval tankers. Purchased in 1955 and 1956 they were sent to Japanese shipyards for conversion (Sasebo Heavy Industries and Hakodate Dock Co. Ltd. respectively) emerging as Atlantic Pride and Atlantic Triumph, specialist bulk carriers for the transport of iron ore from Venezuela under charter to the United States Steel Corporation.

Soon however C.Y. Tung had accumulated sufficient profits to fund a growing armada of newbuilds, starting with the 22,100grt ore/oil transport Atlantic Faith of 1958, another product of the Sasebo Heavy Industries yard.

Given Japan’s negative impact on his businesses early development it says something of Tung’s magnanimity that most of his new orders were placed with that island nation’s shipyards.

A more prosaic explanation is that Japan was the foremost producer of such vessels at the time, with investment in new infrastructure backed up by streamlined production techniques adapted from American wartime methods.

Growth was swift. A year after Atlantic Faith came Oriental Giant, a 70,365dwt oil tanker which entered the record books as the largest merchant ship ever built, engined, owned, operated and manned entirely by Asians.

Although inevitably overshadowed by the mighty French Line’s France, there was another significant maiden arrival at New York in February 1962 when the elegant flag-bedecked combi-liner Ru Yung (‘like clouds’) which had been launched by Mrs C.Y. Tung on 10th October 1961, sailed through ice flows into her berth, inaugurating Orient Overseas Lines Far East to US East Coast service.

A steady procession of newbuilds emerged over the ensuing years, most from Japanese yards but others constructed in Europe, particularly France and Germany. C.Y. Tung had a particular penchant for elaborate, neatly choreographed launch ceremonies and lavished considerable time and expense towards making them memorable occasions.

He loved getting personally involved in the detail, contributing ideas and invariably conducting guided tours of the newly launched vessels for invited guests.

C.Y. Tung’s personal and professional network of friends, associates and partners continued to grow through the 1960s. Indeed ‘networking’ appears to have come naturally, and he was blessed with another innate advantage for the global businessman, an apparent immunity to jet lag.

He was conferred with honorary citizenship from various US cities, medals, memberships and degrees from several universities. Alongside the growing shipping empire came related offshoots into insurance and finance, fulfilling a childhood ambition to be a banker.

Ship repair was another development and from humble origins utilising a small band of skilled Chinese craftsmen at Junk Bay, he purchased the vast 100,000 ton capacity former Valetta British Naval Base floating dock. He had it towed first to Yokohama, under a lease agreement with Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and later to Hong Kong where it became the fulcrum of a facility to service Tung’s increasing fleet.

Much later, near the end of his life, ship repair morphed into shipbuilding and Euroasia Shipyard Co. Ltd. was formed for the construction of oil rigs to service prospecting in the South China Sea.

He forged agreements and long-term charters with a panoply of national oil companies, including Petrobras (Brasil) and Petromina (Indonesia). To service these charters a succession of VLCCs (Very Large Crude Carriers) and ultimately ULCCs (Ultra Large Crude Carriers) were commissioned, rapidly increasing in size and significance.

C.Y. Tung’s greatest personal indulgence was superannuated liners. As with most matters he started small, buying six German built and operated sixty passenger cargo liners and pressing them into service as Oriental Hero, Oriental Inventor, Oriental Lady, Oriental Musician, Oriental Ruler and Oriental Warrior on a regular Hong Kong to New York service.

In the mid-1960s he purchased Excalibur and Exeter, two of American Exports famous ‘Four Aces’ cargo-liners and deployed them as Oriental Jade and Oriental Pearl on a trans-Pacific service between Hong Kong, Japanese ports and San Diego/San Francisco. Fighting against the prevailing trends Tung believed that he could profitably redeploy redundant liners utilising cheaper Chinese crews and operating under flags of convenience.

In 1968/9 he acquired three of the largest cargo-liners ever built from New Zealand Shipping Company. Oriental Carnaval (ex-Rangitoto), Oriental Esmeralda (ex-Rangitane) and Oriental Rio (ex-Ruahine) operated an around the world service with about 300 First Class passengers sailing from Los Angeles to San Francisco via Panama, the east coast of South America, South Africa, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan and Canada’s Pacific coast.

However, C.Y. Tung’s eyes were firmly set on the biggest prize of all.

It took two bites at the cherry before he secured Queen Elizabeth and for once perhaps, he regretted his perseverance. Having been part of the most successful Atlantic partnership in history (with Queen Mary) and despite a ‘life-extending’ mid-1960s refit, the great ship had been prematurely withdrawn from service in the autumn of 1968 and offered for sale.

Cunard became embroiled in a highly controversial plan to use the ship as a hotel/convention centre at Fort Lauderdale, Florida regaining ownership when the first venture, in which they held a minority stake, failed within three months.

The ship was offered for sale a second time in 1969 and this time C.Y. Tung was amongst the most prominent bidders, offering $7.5 million. The successful bid of $8.6 million came from The Queen Ltd., an American operation with dubious credentials. Debts continued to amass like the marine life on her keel and perhaps predictably The Queen Ltd. filed for bankruptcy in May 1970 owing creditors, including most prominently Cunard, $25 million.

The Queen Elizabeth was put on the market yet again with a one-way voyage to the scrappers of La Spezia in Italy the most likely outcome. Indeed, their pre-auction offer of $2.4 million almost won the day. However, when the formal process was convened one Isidore Ostroff, representing his Hong Kong based client submitted a last minute bid of $3.2 million and on 17th September 1970 Judge Emil F. Goldhaber of the US District Court Philadelphia confirmed the sale. C.Y. Tung finally had his ship.

His first act was to rename the ship Seawise University. Somewhere under that quietly spoken, Buddhist façade an ego was clearly waiting to emerge. The new moniker represented a clever pun on his initials coupled with an unambiguous statement of intent.

C.Y. Tung had long wanted to combine his passions for ships and education and the former Queen Elizabeth was to be the means, a floating University that travelled the globe with about 1,000 students and 800 cosseted First Class passengers.

Problems surfaced almost immediately. C.Y. Tung shrewdly recruited the ship’s former master Commodore Geoffrey Marr, Chief Engineer Ted Phillip and sixteen of his engine room colleagues to advise and assist Commodore Hsuan and a 200 Chinese/ Taiwanese strong contingent of Island Navigation Company personnel with the reactivation of the vessel and sailing her to Hong Kong.

The Cunard contingent were appalled at how quickly the ship had deteriorated and a further 100 Chinese crew were sent to Florida and work started on replacing corroded tubes, so that six of her twelve boilers could be made operational. Additional work involved removing the growth on her hull, repairing navigational and safety equipment to meet Lloyds’ requirements and reinstating the anchors, chains and sufficient lifeboats for those onboard.

Never a man to mince his words, Geoffrey Marr was a strong advocate of C.Y. Tung’s plans but publicly sceptical regarding their chances of success. To Tung’s consternation the former Cunard Commodore told the press that if things went wrong with the ship’s departure from Fort Lauderdale she could become “the biggest damn cork in the world”.

In his usual quietly authoritative manner, the owner called Marr straight away and said, “Commodore, don’t talk like that please. After your comments the insurance people rushed right over and said if he feels it’s that much of a risk, we’ve got to increase your insurance premiums! Please use caution” he implored.

Despite losing another boiler and with the assistance of six tugs Seawise University avoided Marr’s cork analogy and successfully made it through the cut and out to open water on Wednesday 10th February 1971. Nevertheless, her problems were far from over, in fact they were just beginning.

It took an epic 155 days for Seawise University to reach Hong Kong, a voyage in which she was adrift for three days in the Caribbean, required more than two months of repair work off Aruba, initially personally overseen by C.Y. Tung, and subsequently steamed at a sedate 7 to 11 knots via Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town and Singapore.

She had experienced polar winds off the Cape of Good Hope but those onboard sweltered in tropical humidity as she approached her destination. Ironically given her languid pace, Seawise University was forced to spend an extra day furtively steaming between surrounding islands before officially entering Hong Kong harbour on the morning of 15th July 1971.

Publicity en route had been deliberately subdued but the ship’s new owner doubtless enjoyed the spectacle of helicopters buzzing above, pleasure craft jostling for position alongside and elaborate plumes of water from the fireboat Alexander Grantham welcoming his new acquisition to her temporary anchorage in the lee of Kau Yi Chau Island.

Once the monsoon season had passed the ship was moved to a new anchorage at the entrance to the Rambler Channel where the refurbishment started in earnest and the remnants of her Cunard colours, first applied in 1946, were chipped back to bare steel so that she could be primed and receive her new livery.

The refit went much deeper than a superficial paint job and alongside a thorough overhaul of her machinery, wiring was replaced, and new fire-resistant bulkheads were installed with safety equipment upgraded to meet the latest SOLAS regulations.

Visiting in November 1971, Alan Whicker, amongst others, may have been incredulous at the volume of detritus cluttering the open decks and the amount of unfinished work inside, but C.Y. Tung calmly explained how the refit was progressing broadly on schedule and although exceeding initial estimates the additional cost of the work was not excessive. He downplayed the inherent difficulties, including industrial disputes within the workforce.

Not for the first or last time C.Y. Tung found himself trying to prove the doubters wrong. By early January it looked as if he would succeed. Externally Seawise University was radiant in all white (the hull was due to receive a coat of pale grey eventually) and the funnels had received Oriental Overseas Line’s distinctive pale yellow colour scheme and were awaiting their plum blossom motifs.

Internally the first class cabins and public rooms had regained their original lustre with polishing and reupholstered furniture and carpets. Soon she would sail for Yokohama and drydocking in preparation for a 75 day maiden voyage departing from Los Angeles on 24th April, crossing the Pacific via Hawaii and Fiji with calls at Sydney and Fremantle in Australia, Bali, Singapore, Hong Kong and Japan before retracing her steps to Honolulu, Vancouver and Los Angeles. Orient Overseas Line’s promotion of Seawise University leant heavily on the ship’s Cunard history and heritage and unsurprisingly early advertising made constant reference to her achievements as Queen Elizabeth and star-studded passenger lists.

Then tragedy struck. Shortly before midday on Sunday 9th January at least nine separate fires started on what C.Y. Tung affectionately referred to as ‘the last historic ship left’.

Arson was suspected from the beginning and was the inevitable conclusion of an official inquiry undertaken shortly after the ship’s demise. Timed to coincide with the workforce lunch break (Island Navigation personnel went ashore each day) the fires were strategically planned, fanned by the wind funnelling through inexplicably open shell doors and portholes. Despite the brave endeavours of some crewmembers, fire prevention was inept, fire doors remained open, and the freshly installed sprinkler system failed to operate.

The destruction of Seawise University was a huge personal loss to C.Y. Tung. Suggestions that the fires had been masterminded as part of an insurance scam must have been particularly hurtful to him. Thrust into the limelight for all the wrong reasons he kept his own counsel with the support of family, business associates and friends.

A fortnight after the fire he flew into Hong Kong from the United States for an emergency meeting with Group officials, but promptly left for Singapore on the 28th January without meeting the press supposedly due to pressing business commitments. Where he went and who he met in those two intervening weeks only adds to the mystery. He issued a statement admitting that the tragedy had ‘broken my heart’ and thanking the people of Hong Kong for their goodwill and kindness.

Having dismissed the possibility of an accident (cigarette ash, welding or an electrical fault) the Marine Court of Inquiry concluded that the fires must have been started deliberately, however the perpetrators and motive remain unknown.

Talk of an insurance scam was dismissed almost immediately. Anyone who had witnessed Tung’s enthusiasm for the project knew that this was far more than a financial proposition for him.

A second suggestion was that disgruntled workmen lit the fire or fires to prolong the refit, but this was equally unlikely. It soon became apparent that the fires were meticulously planned and co-ordinated to destroy the ship.

Ultimately, by a process of elimination the spotlight fell on either covert action by the PRC (People’s Republic of China) or one of the colony’s organised crime syndicates, the Triads. Whatever suspicions he might have had C.Y. Tung remained tight-lipped, as the inconclusive police investigation stumbled on.

His lawyers dismissed a political motive at the court hearing and if there was a dispute with the influential Triads they were never disclosed. However maybe there were deeper forces at play. Britain and the United States were both courting the PRC and within weeks of the fire President Nixon made an historic trip to Beijing to meet Chairman Mao. In Hong Kong the communist influence was growing daily, organised crime was almost out of control and corruption widespread. Perhaps nobody had a vested interest in revealing the truth.

Although clearly scarred by the experience and pre-occupied with the investigation and logistics of removing the Seawise University wreck, C.Y. Tung was true to his word.

The university at sea concept didn’t die with the former Queen Elizabeth and he promptly bought American Export Line’s modest 14,136grt Atlantic, ex-Badger Mariner for $2.4 million and pressed her into service as Universe Campus. On 4th September 1971 she departed on her maiden cruise and over the next quarter of a century took thousands of students and teachers on enlightening voyages. It persists to this day, Semester at Sea became the most enduring and perhaps appropriate legacy of the great man.

C.Y. Tung’s interest in classic liners

wasn’t diminished by the loss of Seawise University either. In 1973 he purchased American President Line’s famous transpacific liners President Wilson and President Cleveland. They were renamed Oriental Empress and Oriental President, and destined for 100 day around the world cruises, but then the oil crisis hit and Oriental Empress’s maiden voyage was abandoned at the precisely one third distance as she was tethered to the Hong Kong passenger terminal having run out of fuel.

Oriental Empress was duly laid-up finally going to scrappers in 1984 but her sister went to Kaohsiung almost immediately.

Thirsty old turbines were no longer viable yet in March 1974 Tung couldn’t resist acquiring American Export’s cut-price flagships Independence and Constitution. As Oceanic Independence the former was refitted and operated for a single season out of Cape Town and Durban in 1975, but Constitution was sent straight into lay-up, joined by her sister in 1976, and never sailed for the Tung Group.

C.Y. Tung may have loved old liners, but he was no luddite. The Tung Group was at the forefront of shipping innovation and perhaps this was best illustrated by Tung’s investment in containerisation.

It all started with eight converted Victory ships capable of carrying 300 TEUs each, although the first voyage from Hong Kong to Long Beach in November 1969 sailed with just 13 containers onboard. From those humble Far East to US West Coast origins Orient Overseas Container Lines (OOCL) steadily expanded so that by January 1972 the Far East to US East Coast cargo activities had been fully containerised. Other routes soon followed, to Northwest Canada, Australia and Europe with most of the conventional cargo liner fleet converted to container ships including the pioneering Ru Yung, and Oriental Queen.

By the end of the decade Orient Overseas Container Line was firmly established with a fleet of 22 ships servicing eight routes with a capacity of 30,000 TEUs. Interestingly OOCL has recently introduced the first of a new class of containership which can almost carry that payload on a single vessel!. There was significant investment in new bespoke tonnage and the Tung Group branched out into logistics and port management with interests in container terminals across the globe from Hong Kong to Felixstowe.

However, oil tankers had been the foundation of Tung’s shipping empire from the start and that suppressed ego and competitiveness surfaced once more in 1979 with the purchase of the longest, largest ship in the world, Seawise Giant (that cheeky pun again).

The Giant was a ship with a chequered past and a somewhat traumatic future. She had been built by Japan’s Sumimoto Heavy Industries yard for a Greek concern but problems emerged on trials and a lengthy dispute resulted in the yard selling the vessel to C.Y. Tung. She became the world’s longest tanker by virtue of the insertion of a 81.45 metre mid-section and when she emerged from the refit and named on 19th December 1980, the ship had a length overall of 458.45 m (1,504.1 ft) a laden draft of 24.611 m (80.74 ft) and a deadweight tonnage of 564,739. CY Tung proudly later introduced a technical seminar on the development of Seawise Giant at Hong Kong Polytechnic, once more feeding into the symbiotic relationship between ships and education that he held so dear.

By the turn of the decade C.Y. Tung and his multitude of business interests were superficially flourishing but a recession was around the corner and the huge recent investment in new tonnage became a liability. The Group became embroiled in controversy by the mid-1980s when in the reputedly less capable hands of his eldest son C.H. (Chee-hwa) Tung. Facing mounting debts of $320 million they were rescued not by Taiwanese interests but by a package of measures backed by the PRC.

When the colony was handed over to China in 1997 C.H. Tung was chosen as the first Chief Executive. Perhaps had C.Y. Tung been at the helm the Group would have navigated the troubled times with greater ease, as he had negotiated so many obstacles over the years. Alas it was not to be.

The 14th April 1982 started as usual for C.Y. Tung with his daily meditation. He was fond of telling friends, “I’ve been working seven days a week for the past 40 years”, but today was to be special. After attending his office in the Island Navigation Corporation headquarters punctuated by lunch at the Foreign Correspondent’s Club he headed out to the airport to welcome Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco on a visit to the colony. Like so many foreign dignitaries he knew the couple well but as the Principality’s Honorary Consul to Hong Kong, he had taken it upon himself to host a lavish party in their honour.

He felt unwell at the airport and went home, subsequently lost consciousness and was taken to hospital. In the early hours of the following morning, oddly and coincidentally almost exactly 70 years after Titanic foundered, C.Y Tung passed away, the result of a heart attack.

His family, friends and the shipping fraternity were shocked at the news. The 150 vessels of the Tung Group fleet flew their flags at half-mast and later his ashes were scattered from the decks of Universe in the Pacific Ocean, China Container in the Indian Ocean and Canadian Explorer in the Atlantic Ocean. The Buddhist funeral lasted three days and was attended by thousands.

Amongst the pallbearers were Prince Rainier, Sir Philip Haddon-Cave (Hong Kong Chief Secretary) and the chairmen of many prominent Hong Kong shipping, business and banking institutions. C.Y. Tung would have been particularly pleased that amongst them was L. Huang, Chancellor of the University of Hong Kong.

Messages of condolence came from across the globe and tributes were forthcoming from a broad spectrum of business associates, friends and admirers.

Many referred to his astonishing achievements condensed into those 71 years but almost all bore testimony to the manner that made him unique, “a kindly, generous, modest man who wore the mantle of greatness with an easy unselfconscious charm”.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item