1939: The Clouds Begin To Gather

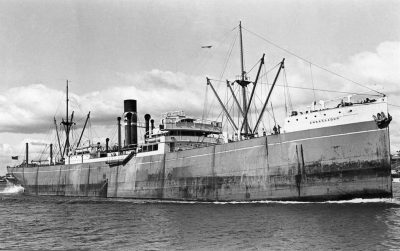

SS Ambassador

In April 1939, I was Second officer of Hall Bros’ SS ambassador under Captain Newman. We arrived at the North island, New Zealand, with a cargo of basic slag from Immingham and we discharged cargo at Auckland and New Plymouth.

While in port at New Plymouth our agent, who was a member of the Taranake alpine Club, persuaded me to join them while they climbed Mount Egmont. Without proper gear I was petrified at times, but achieved the snow line and, for my efforts, was made an honorary member of the club.

our next port was to be Newcastle, New South Wales, and we sailed there in ballast. Unfortunately, whilst there, I was taken into hospital with suspected peritonitis and the SS ambassador had to sail without me. She dipped her ensign as she passed the hospital and the nurses had me propped up in bed and waved a sheet in reply. Fortunately the problem turned out to be kidney stones. When I recovered and was discharged from hospital, I was to be sent home as a D.B.S. (Distressed British Seaman). That sounded terrible and I asked the agent to find me another way home!

SS Salvus

It happened that the SS Salvus, which was in port discharging a load of phosphate from Narau and was then due to load for the UK, needed a Chief officer. I was offered the job.

I had a first mate’s ticket but had only been a Second officer for 6 months and was therefore a bit doubtful. I went for advice to the Chief officer of another British vessel in port.

“Accept, and bluff ‘em mate“ were his words, and I signed on Sunday. The Captain, W. C. Smith, had white hair and looked every inch a gentleman.

What they didn’t tell me was that there had been a mutiny and a murder on board whilst the ship was in Shanghai, that the crew had been exonerated by the British Consul due to extenuating circumstances but were very unsettled. The Captain apparently lived up to his initials! No wonder they needed a new Chief officer. I wondered what I had let myself in for.

On Monday morning four apprentices turned out, but no sailors. The bosun told me: “You’ll get none of the deck crew to turn to, if and when they arrive!”

We stood on the gangway for the remainder of that Monday and I spoke to each deckhand as he came aboard. The next day they all turned to and worked, and I must tell you that they turned out to be one of the best crews I ever had.

We left Australia with a cargo of steel and air raid shelters in June 1939 and called at Durban and Dakar for bunkers on our way home. at Dakar, two doves flew on board and decided to travel with us, sleeping in the lifeboats at night.

We were off Finisterre when war was declared and the U-boats were there, ready and waiting. Ships around us were caught, but we were lucky and arrived with our escort of doves at Swansea without mishap. Seamen are superstitious. We all felt that those two birds had boosted our morale and brought us safely home. as soon as we were snug in harbour, they disappeared.

After discharging our cargo, we sailed to Cardiff for dry-dock. The first person I saw when I went ashore was the old Spanish bosun Ramirez from my apprentice days. He had taught me a great deal of practical seamanship in those early days, although we had always laughed at his broken English. He was now retired.

“You really Chief officer?” he said as we met.

“Yes.”

“When I sail with you, you were one impudent boy. Now you one really gentleman.” What an accolade from a wonderful bosun!

SS Bancrest

Captain W. C. Smith wanted me to stay, but I was anxious to return home to see my parents and to call in Newcastle at the Head office of Hall Bros. The ambassador was in dry-dock at South Shields and Captain Newman was there with her. She had been sold prior to the outbreak of hostilities and had been renamed SS Bancrest. Captain Newman introduced me to her new master, Captain Tuckett, and with very little persuasion from the two of them I joined as Second officer. We signed on November 13th and several weeks later sailed for America. The Battle of the Atlantic had begun, but although much happened on the outward voyage it was mainly bad weather that bothered us and she was a very happy ship.

Third officer Liddle always jumped with gusto into his bunk. I decided to substitute twine for his spring mattress and the next time he jumped he collapsed through into the drawers below! Nothing was said for several days and I thought “Perhaps he can’t take a joke”. However, some days later every time I turned in, the smell in my cabin was terrible. I reported to the Chief Steward and, poker faced, he had his department scrub out the cabin. Three scrubs later the smell persisted, until one night I was so uncomfortable that I changed my pillows round and found that a large slice of salt fish had been inserted! Touché The Third officer and the crew enjoyed the joke. all my bedclothes, mattress and pillows were impregnated with salt fish.

Alas, Dick Liddle was killed in an accident on board in Norfolk, Virginia.

We left the USA, unescorted and unarmed, with a cargo of grain for the UK and instructions to proceed north through the Fair isle Channel, between Orkney and Shetland, and then south to Hull. The weather was terrible, with mountainous seas and no visibility. For 6 days I had been unable to fix the vessel’s position by sun, moon or stars and I thought we must be heading for Norway! I said to the “old Man”, “Will you please steer SSE, but dead slow?”. after calling me a chump, he agreed and 4 hours later there was a commotion up top. When I went up we were in a land locked bay with cliffs and snow. Captain Tuckett turned the ship round and, until daylight, steamed dead slow in the opposite direction, NNW. Eventually we saw a lighthouse.

We had one Shetland islander on board, able Seaman Isbister, who was at the wheel.

“Och”, he said “That’s Muckle Flugga”.

Muckle Flugga is the most northerly lighthouse in the British isles. We had certainly missed the Fair isle Channel and it was a good job we had turned south when we did. it was wonderful to know where we were and to be able to navigate again. The weather was still terrible and we hugged the land, steaming at the terrific speed of 1.5 knots.

Later, despite poor visibility, we were a sitting duck for three German bombers who came over and bombed and machine-gunned us. The after end of the ship was split open and we were helpless, although still floating. Sparks was able to send out an S.O.S. with our position, 45 miles NE of Wick. Captain Tuckett and three crew members stayed on board in case the S.O.S. was answered quickly, but he ordered the rest of us to leave.

My lifeboat had been washed off the boat deck but the for’d painter had held and we found her under the bows. Seventeen of us boarded her. The Chief officer and others made the second lifeboat.

I had promised Captain Tuckett to keep as close as possible, but the seas were mountainous and despite all our efforts we lost some ground as the hours rolled by. at last someone in my boat shouted: “There’s a destroyer”.

“rubbish’ I said, and bet them a pint of beer each that the crewman was imagining it. Then, as we were lifted up on the crest of one of the huge waves, I was overjoyed to see that he was right. Coming towards us was H.M.S. Javelin.

Commander Pugsley apologised for taking so long. “I could only manage 18 knots in this weather” he said. I heard later that he had split his foredeck in the rush to rescue us.

Again we were so lucky. He had been out searching for a lost Athel tanker, had given up hope of finding her and returned to Scapa Flow when our S.O.S. was picked up. He was able to turn round at once and rush to our rescue. We were picked up and, as the Bancrest sank, Captain Tuckett and two crewmen were rescued from the wreckage. alas the one man lost was our Shetlander Isbister. after a few hours search, the second lifeboat was picked up intact.

Years later in the Missions to Seamen chapel in Geraldton, Australia, I saw a painting behind the altar. I have a photo-graph of it at home. it shows a destroyer racing to rescue some sailors stranded on a raft in rough weather and in the sea between the destroyer and the raft is the figure of Christ.

On board the destroyer I was treated for frostbite. My big toes have never been the same since! Nor did my clothes survive. The sailor who had taken them to be dried whilst we were wrapped up in blankets was washed over board and had to let go the bundles of clothes while he grabbed a lifeline. Fortunately he was washed back on board. I told the First Lieutenant and he sent for a. B. Jones.

“What’s this about you being washed over board and why wasn’t I informed?”

“Didn’t think to bother you, Sir! it’s the second time it has happened this passage”.

The Javelin, having at last sighted the “lost” tanker on the way, took us into Leith.

Some of us went ashore in borrowed clothes. Sparks insisted on travelling home as he was, bell bottomed trousers and all. He wanted his family to see a shipwrecked mariner! The First Lieutenant supplied me with a pair of white flannels, so big they were tied under my armpits with cord, a navy jersey that came down to my knees and a pair of sand shoes.

Our agent asked one of the big stores, Thomson’s of Leith, if they could stay open to fit us out, so that we could travel home. The full staff, including the commissionaire, stayed behind and served us like royalty!

In the meantime my parents had waited for news. The newspapers had reported the Bancrest sunk, but no list of survivors. on the fifth night of waiting Billy the canary, which I had brought home years before, started to sing. it was dark, 9 o’clock at night, and the cage was covered, but the bird sang and sang and my mother said “Geoff’s all right” and stopped worrying.

When they told me I thought they were pulling my leg, but the same thing happened when they were sitting, worried about Dunkirk and wondering if my brother had managed to escape. again I was sceptical but I was home on leave when Liverpool was being bombed night after night. My sister Eileen was nursing in a big Liverpool hospital and again, as we sat one evening wondering and praying that all was well with her, at 10 o’clock at night the house was full of bird song. I went into the kitchen. The room was in darkness, the bird cage was covered, but Billy was singing his heart out. Then the telephone rang and Eileen told us she and her ward were OK in spite of the blitz.

Those were the only times we heard Billy singing in the dark. Unbelievable but true.

So ended the life of SS ambassador/ Bancrest on which I served so happily. But it was not the end of Crest ships. For the owner of Yugoslav Lloyd sold all his ships to England for a nominal amount. The Preradovic was renamed the Fircrest and there were many more. I served on the Fircrest, the Ashcrest, Helencrest and Suncrest, all of which continued the war against Hitler as long as they could.

Later in 1940 I was ashore in Liverpool sitting for my master’s ticket when Captain Tuckett, who had been awarded the O.B.E. for the rescue from the Bancrest, was lost with all hands on the Fircrest. I should have been there with him, but he insisted that I stayed behind and sit the examination. My luck still held!

SS Preradovic

I was on survivor’s leave from the Bancrest when Capt. T. rang me and asked me if I would join him and others to bring the SS Preradovic out of Antwerp. My second effort as Chief officer.

We went by ferry to Ostend, stayed a night in Brussels (where the Second Engineer gave a fifth columnist the “bums rush” because he asked too many questions!).

We boarded the Preradovic in Antwerp. She was German built, she had been given to the Yugoslavs after the first world war. She was in wonderful condition. The decks had been coated with olive oil (not common fish oil which we on British vessels had to use) because olive oil was plentiful in pre-war Yugoslavia. We found huge barrels of olive oil, huge barrels of vino (for the crew’s consumption) and in the Master’s locker every conceivable type and colour of liqueur and wine. The Master and Chief Engineer plied me with a good few samples, and who was I to refuse an order from the Bridge! What fun we had pronouncing the name, and hoots when others tried in vain to pronounce it!

Of course the vessel was painted with the colours of Yugoslavia, red, white and blue. The authorities ordered these to be painted out, and with tongue in cheek I agreed to do this. I gave the Bosun instructions but somehow forgot the aerial- seen colours. I wanted to get home safe! The engineers had a hard 36 hours translating German names on valves but they made it. They were a great bunch of shipmates. I will always remember Second Engineer Sigworth. one day I happened not to have heard him and I said “What?” He replied like a shot “Don’t say “what?”, say “Eh?” like your father does!” This was a great joke as my father was very correct in speech as in all things. This was the beginning of all too short a friendship.

We sailed for the Tyne, but hadn’t time to adjust compasses, so about 5 o’clock in the morning I sighted a strange light and called Capt. T. to tell him I thought we were too far north and had sighted Coquet island. in war time only a few lights were burning and it was indeed Coquet island. it was almost dawn and to Northerners it was easy to follow the coast back to the Tyne by way of Newbiggin, St. Mary ‘s island, St. George’s church, (not forgetting the Spanish City dome) and the Tyne piers.

I was all set to sit for my Master’s ticket, but alas I was ten days short of “sea time”. I could have stayed with the Preradovic (now renamed the Fircrest), but the others insisted that I sit for my Master’s Certificate. I decided not to do this in Newcastle. When I was ashore from the Bancrest I was invited to a Merchant Venture’s dance for the Altmark survivors, and during the Paul Jones, when dancing with a beautiful young lady, I made some incautious remarks about the Senior Board of Trade Examiner who was also present. imagine my horror when I saw the same lady sitting chatting at his table. I asked my host who she was and was told she was the Examiner’s new wife. Hoist with my own petard! I knew it would be safer to be elsewhere for my examination!

Continued next month

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item