The Porcelain Port

By Patrick Boniface

When one looks at a pretty and delicate china mug or coffee cup one doesn’t often think of what went into making it; the skill of the craftsman who fashioned it much less the materials used to make it. So it may not come as much of a surprise to learn that many people don’t know the connection between the small Cornish port of Charlestown and the cup of tea or coffee they’re drinking.

When one looks at a pretty and delicate china mug or coffee cup one doesn’t often think of what went into making it; the skill of the craftsman who fashioned it much less the materials used to make it. So it may not come as much of a surprise to learn that many people don’t know the connection between the small Cornish port of Charlestown and the cup of tea or coffee they’re drinking.

The connection is china clay. The landscape around St Austell in Cornwall is dotted with small quarry workings where this valuable mineral has been systemically ripped up from the ground to be sent north to the hundreds of potteries that once existed in and around Staffordshire. With such bulky loads it was never going to be a practical solution to send it via road or railway. The only solution was by sea.

The Chinese, quite rightly, up until the mid 18th Century held onto the secret of how to make delicate chinaware. This closely guarded secret had allowed China to develop a lucrative marketplace for its goods across the world. Inevitably the secret was discovered that Kaolin (China Clay) was used in its manufacture and deposits of the mineral were found in Cornish granite. The substance had been used in building work and was also found to be in early mortars. It took the work of one industrious chemist from nearby Kingsbridge in Devon, William Cookworthy, to uncover the properties of the mortar. In 1768 he patented his discovery and ever since the product has been known as China Clay.

Cookworthy in 1768 established a small pottery business in Plymouth before moving to Bristol, and was forced to sell his interests after financial difficulties to his partner Richard Champion. China Clay had by this time become ‘hot property’ as its use in the pottery industry gave the smooth, silky, porcelain finish everyone wanted on their dinner tables. Champion unsuccessfully applied for an exclusive 14 year patent extension on China Clay’s use but was fiercely opposed by manufacturers led by the famed Josiah Wedgewood.

When the patent was effectively refused a number of speculators and businessmen arrived at St Austell and set up extraction services in order to dig up as much China Clay as it was possible to find. The old tin mines in the region, stripped of metal proved to have a second life pulling Kaolin from the granite instead. It was still a labour intensive operation. 7 tons of granite produced only one ton of Kaolin. The Kaolin then needed to be washed and sorted. The waste material would be dumped and today still tower over many communities as giant mounds which nature is slowly re-establishing her foothold on.

The Kaolin settled into lakes, which was later dug out for transportation, which was where lay the biggest problem for the businessmen of Cornwall. The road network in the 1700s was notoriously bad and the only effective route to the potteries of Staffordshire was by sail ship around Lands End and into the Bristol Channel and then the port of Bristol from where it could be trans-shipped onto barges for the inland canal network.

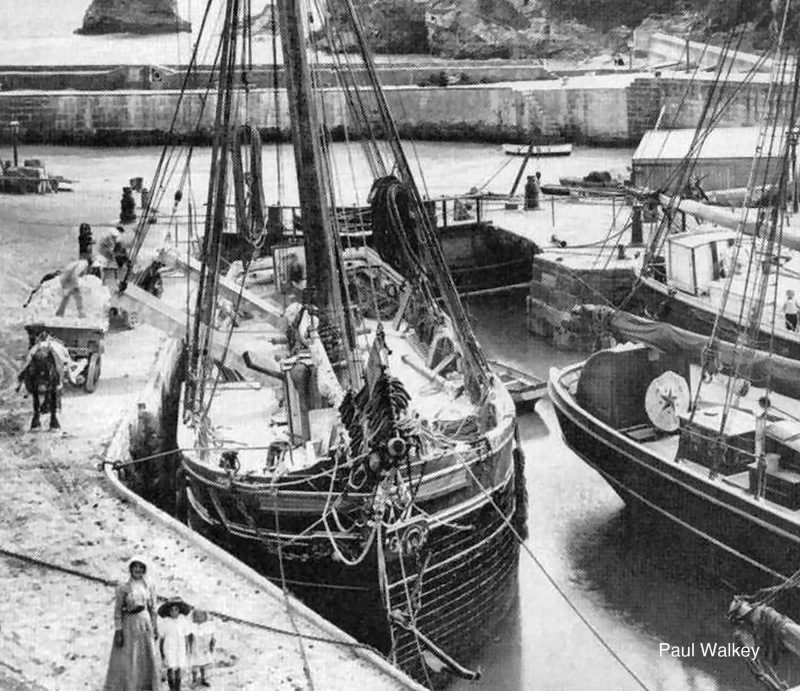

In the early 1700’s port facilities in Cornwall were few and far between and the nearest harbour at Pentewan was not in a good state of repair. Pentewan was also a considerable distance from St Austell. The only option was to load beached boats that were hauled up on the beach at West Polmear, which only really was possible during the summer months when good weather was more predictable. Even still by the 1780s 500 tons of China Clay was being transported in this manner.

This situation could not continue if the industry was to provide the goods the potteries were crying out for. What was needed was a more reliable port from which larger vessels could be loaded directly and to which regular service routes could be established.

A local businessman by the name of Charles Rashleigh had been watching the situation with interest. He lived only two miles from the beach at West Polmear and he proposed a solution. Rashleigh had discussions with the 18th Century engineer John Smeaton who had recently created a modern harbour in St. Ives Bay. He proposed using land his family owned at West Polmear for the construction of another harbour. Rashleigh was a determined, some might say ruthless, entrepreneur but he could see an opportunity when one presented itself and he was quick to act.

The rocky cove at West Polmear was chosen as the site for his new port and the first soil was turned in its construction in 1791. In 1792 a harbour wall and a pier were built, whilst later in the year an outer basin had been completed. Then the workmen were set to digging out the inner or floating basin, where vessels could load and unload their precise cargoes of Kaolin in all levels of tide in safety. Navvies hammered at the local granite with pick axes and spades eventually removing thousands of tons of spoil to create the basin. Massive iron lock gates were built and brought to the port, which received its first ship in 1796, five years after work on the project had started. The new port needed a new name and it was named after Charles Rashleigh being given the name of Charlestown.

In 1801 the threat posed to small ports like Charlestown from Napoleon Bonaparte’s forces on the Continent was immense and a four gun 18 pounder gun battery was built overlooking the port.

Rashleigh’s expensive gamble in creating a new seaport proved to be virtually an immediate success. Thirty to forty wagons of China Clay were handled every day. Sadly the local environment around Charlestown suffered with the extra wagons churning up the countryside and inadequate local road network.

Prospectors, searching for rare minerals and metals in the early 1800s, found large deposits of copper and this metal was soon also being shipped from the port in large quantities.

When Charles Rashleigh died in 1823 his port was a success despite competition from ports at Pentewan and Par. By 1850, 15,000 wagon loads of China Clay were being shipped annually alongside similar quantities of copper, coal, timber and general cargoes. The clay business remained largely seasonal and confined to the summer months when it was easier to handle. From 1850 to the turn of the 20th Century the demand for China Clay from around the world doubled especially to growing markets in Scandinavia and St. Petersburg in Russia.

In 1871 new lock gates were added at Charlestown and the inner dock basin was extended. This was a direct challenge to the emerging port of Fowey, which with its railway connection was stealing business from Charlestown. Charlestown also innovated with the provision of clay drying sheds located next to the port itself. The Lovering Dries at Charlestown remained in operation until 1970 when the business transferred to Par.

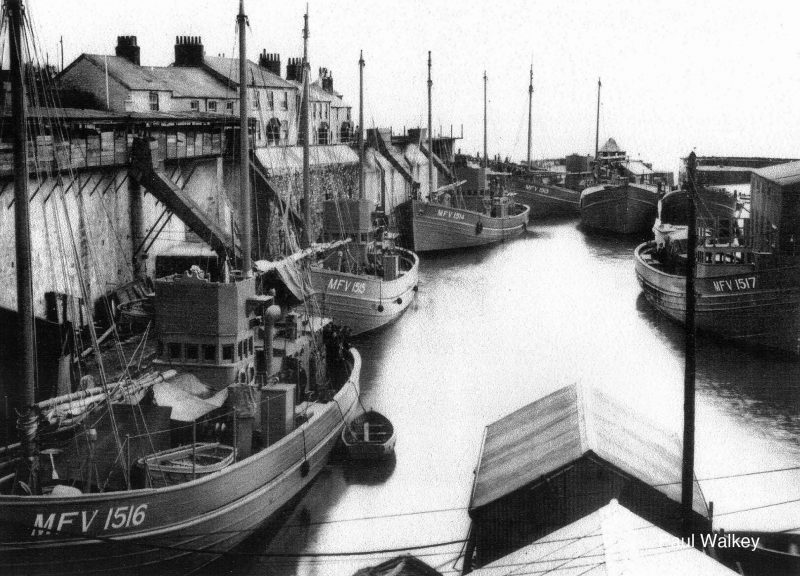

Charlestown wasn’t just about China Clay, however, from 1790 the port was also the site of a small shipbuilding industry, both inside the basin and on the nearby beach. However this industry had ceased by 1875. There was also a small fishing fleet that caught and traded pilchards.

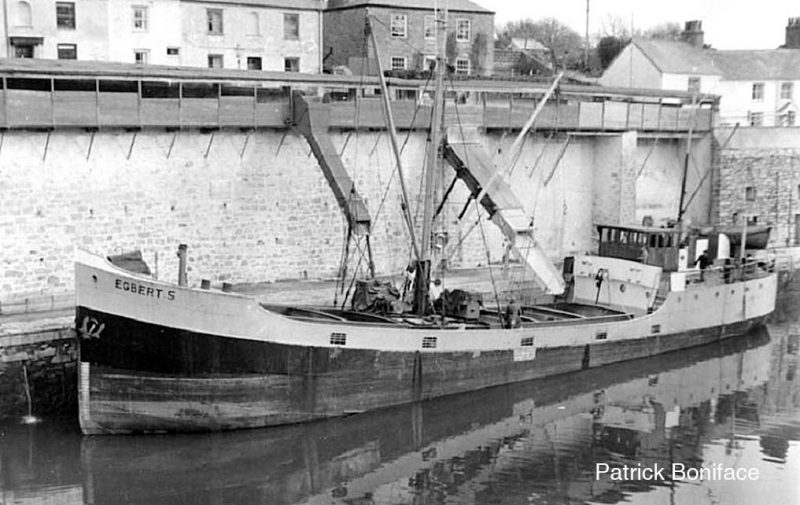

In 1919 the three largest producers of China Clay at St Austell realised that savings could be made if they merged their operations and became English China Clays. A direct consequence of this action was that most of the China Clay produced was directed via Par and Fowey. The Second World War placed severe demands on Charlestown and its wharves were used to fit out minesweepers built at Par and to repair and refit numerous other vessels.

Post war the port business slowed considerably but owing to its original Georgian port appearance it frequently is in use as a film set most notably during the Michael Caine classic movie ‘The Eagle has Landed’ and most recently the 2015 television adaptation of Poldark.

In 1971 the lock gates were, once again, improved by the installation of modern Dutch sluice gate type. The basin was also dredged to allow larger vessels with deeper draft to use the port. Ships up to 600 gross tons can be accommodated but only at the highest tides and then with a great deal of human effort. Interestingly the harbour’s size proved to be its downfall when in the year 2000 the last export of china clay left the port. Six years earlier ownership of the port of Charlestown had transferred to Square Sail. Twelve years later the owner of Square Sail, Robin Davies, put the port up for sale for £4.4 million.

Today the port is home to a small fleet of tall ships including the Kaskelot and is a tourist hotspot with many people exploring the area’s maritime history and secrets at the Charlestown Shipwreck, Rescue and Heritage Centre with many fine exhibits including a 400 year old cannon, Nanking porcelain and recovered items from the tragedy that befell HMS Ramillies in 1763. The most recent addition to the centre’s collection is the RNLI lifeboat Aurelia.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item