The first purpose built Offshore Vessel

by Vic Gibson

In 1955 Elvis Presley signed with Sun Records and was voted most promising male country star at the annual country disc jockey convention in Nashville. At the same event he was approached by a songwriter with “Heartbreak Hotel”. It was the King’s first recording with RCA Victor and was to go to No 1 the following year. Elsewhere, in the heartland of America, Henry Ford initiated the production of the Ford Thunderbird in competition with the Chevrolet Corvette which had recently appeared on the sports car scene and during the year businessman Ray Kroc purchased the burgeoning burger chain from the McDonald brothers. On 25th March of that year, almost unnoticed by the mainstream population of the country, a small ship made its way down the Missisippi and changed marine support to the offshore oil industry for ever.

But not wanting to get ahead of ourselves we should maybe look back to events at the turn of the 20th century as the oil industry in the southern states was almost randomly drilling holes in the ground, with the steadily reducing chance of striking oil. The process was known as “wildcatting”, with the embrionic industry focused on discovery of new reserves, rather than the proper exploitation of those that had already discovered. In that environmen the oil seeps and visible gas discharges were attractive to the wildcatters, and as early as 1870 gas was discovered in a well which had been drilled in order to supply water to an ice works in Shreveport, a town in the vicinity of Lake Catto. Later, in 1904, positive efforts were made to drill for oil in the locality, and in 1905 the first of a number of fires due to high pressure gas occurred. When wells caught fire they were just left to burn. Gas wasn’t much use to anyone so they thought.

Then Gulf Oil (now part of Chevron) decided to build platforms on the lake from which drilling could be carried out. The company developed a process which involved piles cut from the woodands in the area and oilfield equipment brought up the Red River by barge from Baton Rouge, a trip of about 300 miles. Their first well drilled over water, “Ferry Lake No 1”, was completed by the company in May 1911. Fortuitously they struck oil, the well producing 450 barrels a day.

Several companies then took up the challenge of drilling over water in Lake Maracaibo using the experience gained in Lake Caddo, and intially it seemed that the same technique could be applied. Unknown to the drillers, the wooden piles proved to be attractive to the Teredo Ship Worm which, once it had found a platform, would eat away at it until finally, without warning, the whole structure would collapse into the water. Hence by the 1920s concrete piles were being used in the lake and later, in the 1930s, steel structures. In the same decade the companies found that, while they needed to install the derrick on a permanent base, they could use a tender vessel with all the support systems on board. The one thing which was universal to the whole process was the use of the same plaform that had been used for the drilling operation for the production of the oil, but as time passed, and the likelihood of an oil strike as the result of every drilling operation decreased, a change was considered.

Enter Louis Giliasso, who had been a merchant marine captain, and had worked in the Venezuelan oilfields in the 1920s. He applied his marine knowledge to the requirement to be able to move all the drilling equipment in one shot, and designed a barge which could be sunk to the seabed, then once the hole had been drilled, successful or not, it could all be moved on. But the idea did not light anyone’s fire in the oil industry and so he shelved the whole thing, and moved to Mexico where he opened a bar. Later, Texaco then the Texas Company, exploring the same idea, found that Captain Giliasso had taken the precaution of gaining a patent on the design, and so with some effort they located him. He allowed them to build the first mobile drilling unit, fittingly called the Giliasso, and it went to work in 1934 in the swamps of Louisiana. The drawback of it was obviously that it could only work in water depths which were slightly less than the depth of the barge from deck to keel.

Without much further forward progress, at least in the offshore business, America entered the Second World War, but when the men who had been in the fighting returned home they applied themselves to further activity in the Gulf of Mexico. The Magnolia Petroleum Company built a platform eight kilometres off Point Au Fer, on which not only was there a drilling rig but also the following as listed in the book “50 Years Offshore” by Hans Veldman and George Lagers; “diesel engines, mud pumps, a mudpit, a freshwater tank, a mud mixing installation, a cementing pump, fuel tanks, a tool shed, a drilling shed, a radio room and an office”. This list gives you an idea of the difference between operating commercial vessels whose job is purely to carry cargo between A and B in as large a quantity as possible, and the requirement for a ship to fulfil the diverse needs of the offshore oil industry. And while there is no record about how the various supplies were ferried out to the Magnolia platform, the records do say that a couple of shrimpers were used to transfer personnel between an accommodation ship moored close to the shore and the platform where the work took place. Veldman and Lagers did not bother to explain anything about the commodities list, and while we can see the need for fuel and water what about mud? Mud was, and still is, the name given to drilling fluid, which in those days was the mineral baryte, supplied to the rig in bags, and mixed with fresh water. This liquid was pumped down the centre of a rotating drill string (in itself an inovation back then) and flowed back to the surface, carrying with it the debris from the bottom of the hole, as well as providing a hydrostatic head to keep any hydrocarbons down there. The cement, used to keep in place the tubing used in the well, would also be shipped out in bags.

After Magnolia’s groundbreaking efforts others followed, the most noteworthy for our story being Kerr-McGee, who obtained licences in three blocks in the Ship Shoal area and contracted with Brown & Root to provide engineering expertise. Thereafter one of the principals of the company toured harbours containing surplus wartime vessels and bought two Yard-Fighter barges, one LST (Landing Ship Tank) and three air-sea rescue vessels. Hence Brown and Root built the platforms which housed the drill floor and the derrick and the company moored a barge up to it carrying all the other equipment, then they supplied the site by means of the LSTs.

At the time their marine superintendent was a former naval man, Alden J “Doc” Laborde, who was convinced that the way forward was to develop a mobile drilling unit which would be able to move from place to place, with facilities for everything that was required. This sounds a bit like the Giliasso, but the Laborde idea was that there should be a hull on which would be mounted a number of columns, and then on top of the columns, a deck with stores, the mud pits, the drill floor and the derrick, not to mention the necessary diesel engines to keep it all working. However, his employers were not interested, and so he went out on his own, found some investors and built their first mobile unit, the Mr Charlie. Other mobile units had by now also been constructed, one or two of them standing on legs, making mooring to them particularly difficult.

Many companies had by now purchased war surplus LSTs. They had some of the features the industry required, principally an open deck unencumbered by any of the stuff usually seen on merchant ships – masts, funnels and ventilators – mostly positioned just where it would be a good idea to place the cargo. However the conning position was at the stern and did not provide much of a view, and the open deck was central between tanks along the sides so limiting the space available. And, probably not entering much into anyone’s thinking, was the fact that they were pigs to drive. So Doc Laborde, having initated ODECO, a company we were to hear much of later, not really in a good way, decided to build a ship specifically for the offshore business.

There were, at that point, some things that were a given in ship design. A bow was required so that it could cleave the waves and house the anchors, one or more propellers had to be positioned at the stern, with one or more rudders and somewhere the engines had to exhaust to the air. The ship also had to be small enough to be manoeuvrable, since when it arrived at an offshore installation it had to be able to position itself under a crane by tying up in some way. And in addition to these requirements it had to have a large open deck on which the cargo could be carried. Taking everything into consideration Doc Laborde sketched the ship on the back of an envelope.

In July 1954 Tidewater Marine Services Corporation was incorporated in Louisiana with a number of investors and one employee, the marine superintendent, Bill LeBlank. He goes down in history as the man who said, on observing the design, with the wheelhouse and accommodation on the bow, that it would “pound the crew unmercifully”. No-one who has ever sailed on a supply ship would dispute the statement.

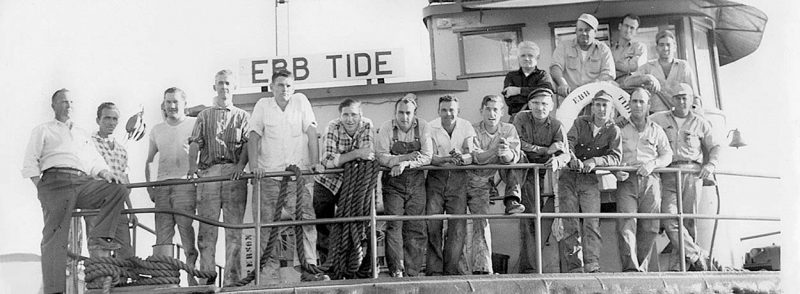

But Doc Laborde was not put off and the design was refined in the Alexander Shipyard, taking into account the provision of second hand engines and the wheelhouse from a tug, provided by one of the investors. The resulting vessel, costing $225,000, the Ebb Tide, was 120 ft long with an open deck aft of the forecastle area 90 ft long and 27 ft wide. The funnels were situated close to the stern on either side, and were low enough not to form any sort of obstruction during cargo work. The ship had a light draught of 5 ft and a loaded draught of 8 ft 6 in, the GM tug engines developed 600 bhp collectively giving it a top speed of about 10 knots. The liquid capacities were 330 tons of ballast and 110 tons of fuel.

As soon as the ship entered service it was chartered by ODECO, but Shell immediately put their name down for the next vessel of the same type, and so Tidewater constructed the Rip Tide which was a more or less identical 120 ft ship. Further oil companies also wished to have the opportunity of using the new vessel type, and so the construction industry took to its heart the new designs. American shipyards can really produce vessels at an amazing rate, and so by the end of its first year of operations Tidewater was operating 11 supply ships, bear in mind that this was from a standing start. After building half a dozen 120 footers the company went on to develop vessels 136 feet long, and and then 142 feet and so on. And in order to keep the increasingly large fleet employed the company was forced to extend its area of operations. The photograph of the Ebb Tide was taken at the time of its departure to Lake Maracaibo. A close look also shows that it was pretty battered, probably after quite a short period of service, and might prompt a question as to how precisely these craft were operated. The strength of the design was that the whole of the open deck could be put alongside a platform and, with some manoeuvring, be tied up stern to mobile units with a couple of ropes.

The captains were probably ex-tug men, who were familiar with the capabilities of small ships with two engines, two propellers and two rudders. They had the benefit of being able to look through the windows at the back of the wheelhouse, and be able to see the whole of the ship and so were able to put the deck within the range of the rig crane. In sufficiently shallow water this was probably achieved by dropping an anchor while heading in towards the rig, and then, when close enough, swinging round to present the stern, the crew would take a rope from the crane and turn it down on the aft bits. This sounds easy, but was a process fraught with tension.

This basic form of offshore vessel was not to change for almost 20 years, when the offshore oil industry moved into more harsh environments, including the North Sea. The Ebb Tide II for instance, built in 1973 although now 180 feet long with engines developing 2,250 bhp, still had low funnels half way down the main deck. But their days were numbered, and in order to prevent the engines being put out by big waves, the funnels were moved to a position just aft of the accommodation and mostly extended to a point above the wheelhouse, although one thing did not change – the crews were still “pounded unmercifully”.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item