The World’s Most Complete Transportation System’. In this age of advertising hubris it is easy to dismiss this marketing slogan, as yet another example of commercial hyperbole. Yet there was much truth in the statement. Canadian Pacific truly spanned the globe. The first White Empresses with their elegant clipper bows (complete with bowsprits) and counter sterns inaugurated a trans-Pacific service in 1891. Transatlantic crossings started in 1904 with the acquisition of Beaver Line, Canadian Pacific introducing its first new builds years later. The Atlantic and Pacific oceans were linked, from Montréal to Port Moody, by the company’s famed railway system, and supplemented by a portfolio of magnificent hotels across the Dominion.

Canadian Pacific’s zenith was in the inter-war years. In 1931 they introduced the magnificent Empress of Britain, a vessel of 42,348grt that eclipsed any rival tonnage on the Canadian route and the majority of competitors sailing to New York. Famed for her annual around the world cruises, with two of her four propellers and shafts removed and a reduced complement of millionaires on board, she forsook the ice bound St. Lawrence and steamed at a leisurely pace encircling the globe. The Second World War decimated the Canadian Pacific fleet. Losses included Empress of Asia, Empress of Canada, Duchess of York and Duchess of Atholl but most tragically the beloved Empress of Britain. Abandoning the trans-Pacific service, the company introduced modest cargo liners to supplement a post-war transatlantic passenger service. This was headed by Empress of Scotland, originally the 1931 built Empress of Japan, Empress of France and the hastily purchased French Liner De Grasse, which was renamed Empress of Australia.

Investment in new tonnage was a priority and initial orders were placed with Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Ltd. at Govan and Vickers-Armstrong on the Tyne, for two 25,500grt sisters. Completed in 1956 and 1957 respectively, the Empress of Britain and Empress of England regained Canadian Pacific’s pre-eminent role in the service to the St. Lawrence. A great deal of research had gone into their internal and external design, creating very modern vessels to compete with Cunard’s Saxonia quartet. Nevertheless, after appraising the performance of the new Empresses and with the timely sale of veteran Empress of Scotland, Canadian Pacific decided to order a new, larger flagship. She would prove to be their last.

To build this new vessel they turned once again to Vickers-Armstrong, where the first keel plate was laid on the slipway on 27th January 1959. Sixteen months later, on a bright May day, the flag-bedecked hull was named Empress of Canada by Mrs John Diefenbaker, wife of the Canadian Prime Minister, and slid into the Tyne to the cheers of thousands spectators bordering the slipway and lining the opposite bank.

The ship that emerged over the following seven months was a slightly larger, updated version of her predecessors. Those attending the launch could not help but notice the bulbous forefoot to the bow, a company first designed to optimise water flow, reduce fuel consumption and increase speed. The sculpted cruiser stern with integral anchor housing was retained from the earlier ships but the eagle eyed would also have noted stabilizer housings on each flank, again a company first, which could reduce rolling by a third. Welding was used extensively throughout and plating at the forepeak and along the flanks around the waterline, was specially ice strengthened. Although not immediately obvious, considerable time was also spent optimising the new vessel’s rudder design, to improve manoeuvrability in the confines of the St. Lawrence. In February 1961 the structurally complete liner was manoeuvred along the Tyne to Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson’s yard at Wallsend for dry docking. She presented a very handsome and sturdy profile, more harmonious than her predecessors primarily thanks to the observation lounges and covered games area located aft of the bridge and the larger tapered funnel, featuring grills at both front and rear to create an updraft and thereby take smoke clear of the aft decks. A subtle touch was incorporating curves to the checkerboard funnel logo to mirror those on the top of the stack. The single aluminium mast was of a thicker contemporary design with unique grill like yard arms. Aft of the funnel were two, small, athwart ship masts, similar in design and function to those on the France, then building at St Nazaire. Echoing the funnels frontal rake these added to the ship’s overall balance, whilst also providing a functional exhaust. The rear decks were tiered towards the stern and lifeboats housed in a conventional position, on davits above the narrow outdoor promenades. If there could be any criticism of the silhouette, it was the preponderance of cargo handling kingposts and the jumbled configuration of decks below the bridge. Cargo capacity was significant, with almost 280,000 cubic feet for a diverse range of products from grains to machinery, and including over 16,000 cubic feet for refrigerated goods. The four holds were split evenly fore and aft and serviced by three pairs of kingposts. One pair were incongruously located straddling the bridge, where they dominated the forward end. When Carnival removed them along with the aft pair at a later refit it certainly enhanced the ship’s looks.

The Empress of Canada’s interior design and décor was co-ordinated by the Glasgow architect J. Patrick McBride and the London-based consultant Paul Gell. Considering her duality of purpose, summertime two class liner and wintertime single class cruise ship, the intention was to create rooms to meet both roles with no clearly defined class distinction. Indeed public rooms were not designated First or Tourist class, instead all were given Canadian themed names and décor with the exception of the Mayfair and Windsor Lounges (respectively the main first and tourist class public spaces in transatlantic service). Pale wood panelling predominated whilst the largest public room on board, the two deck high Canada Room ballroom, was a light, airy modernistic space, with a golden colour scheme and curtaining and a gallery overlooking the dance floor. Recessed lighting in the squared dome could be dimmed to match the musical mood. Like the large cinema, it was available to all passengers irrespective of class on transatlantic service.

Convention dictated that separate dining rooms serviced each class. First class used the Salle Frontenac with its sunken central section and restrained gold and blue colour scheme, whilst the more vibrant tourist class Carleton Restaurant included mural depictions of the Canadian landscape. Traditionalists baulked at some of the more elaborate décor, despairingly considering it too American. The Banff Club came in for particular criticism, with its mosaic tiled pillars and intricately patterned carpeting. Cabins for the 192 first class passengers were located on Empress and Upper decks. These were large and all featured en-suite facilities. Cabins for the 856 tourist class passengers were predominantly on Main Deck with others located aft on Upper and Restaurant decks. The majority (approximately 70%) had toilet facilities, some with showers. Inevitably smaller than their first class equivalents they all featured lower and fold-down beds in either 2 or 4 berth configuration. A selection of different colour schemes were employed for soft furnishings, with carpeting in first class and linoleum flooring in tourist. The ship and her passengers were looked after by a crew of 510, initially headed by a company veteran, Captain J.P. Dobson, who had served with distinction in both world wars.

On 2nd March 1961 employees and sub-contractors of Vickers-Armstrong were given the traditional opportunity to take family members aboard, to view the fruits of their labours. Four days later she sailed from the Tyne for initial sea trials, testing her machinery en route to the Clyde. On 10th March she left ‘Tail of the Bank’ near Greenock for the first of a series of speed trials on the measured mile off the Isle of Arran. Over subsequent days her two sets of Pametrada double-reduction geared turbines were pushed towards their 30,000 shp limit, achieving a highly creditable 23 knots which allowed plenty of reserve over the 21 knot service speed. After returning briefly to Vickers-Armstrong she finally arrived at Liverpool on 27th March and was presented to travel agents and the media, generally receiving very positive reviews. Almost a month later, dressed overall and with celebratory whistle salutes from tugs and other shipping, Empress of Canada was eased away from the famous pier head landing stage at 6.45am on 24th April 1961. Contrary to public perception late spring can often be tempestuous on the North Atlantic and this first crossing was no exception, with 30 foot waves endured in mid ocean. Rather appropriately given the conditions, Nicholas Montserrat, author of ‘The Cruel Sea’ was onboard that maiden voyage. A week after leaving Liverpool, and having proved her sea-keeping qualities, and the benefits of having Denny Brown stabilisers, she made her first Canadian landfall at Quebec, before steaming up the St. Lawrence to Montréal. This new Empress and her two older sisters were, of course, primarily designed for point-to-point liner services. Although jet aircraft had begun to erode the proportion of sea-going trade, the actual number of people travelling continued to rise. Canadian Pacific remained optimistic about the service’s profitability and Empress of Canada made ten more round trips in 1961, finishing at Liverpool in mid November.

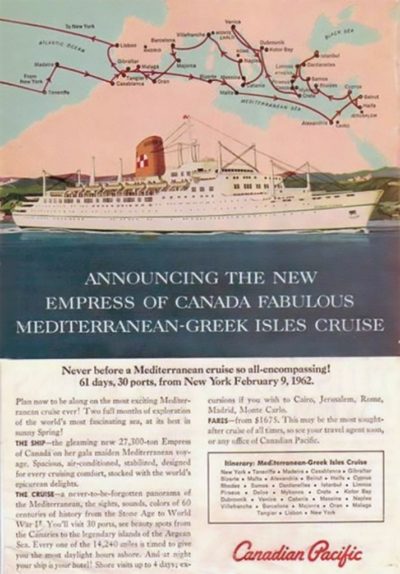

Nevertheless, even more than the southerly New York route, the St. Lawrence service had always been seasonal. Historically Canadian Pacific liners had therefore been designed with winter off-season cruising in mind. Empress of Canada was no exception. Like Empress of England and Empress of Britain, she was air-conditioned throughout and a swimming pool was manufactured to fit into the aft cargo hatch for languid days in the tropics. On 12th December 1961, Empress of Canada departed Liverpool directly for New York. The traditional welcoming armada of tugs and fireboat fountains had to be aborted as the new flagship steamed unseen to her Hudson berth as the Big Apple was enveloped in thick, freezing fog. After successive 14 day cruises to the Caribbean, the new Empress was provisioned for the longest, most ambitious cruise of her entire career, over 14,000 miles to the Eastern Mediterranean and back. Advertised as ‘….. the most exciting Mediterranean cruise ever’ it was reminiscent in concept to grand voyages of an earlier era. With 30 ports of call it was certainly extensive but its true value lay in the time ashore, with up to four days in certain ports allowing passengers leisurely tours of the numerous historic sights. Amongst the highlights were calls at Alexandria for Cairo and the Pyramids, Haifa for the Holy Land, Istanbul, Athens and Venice.

On 12th April 1962, the day after her return, Empress of Canada departed New York bound for Liverpool, before commencing her second Canadian season. After cargo-handling and provisioning at Gladstone Dock each crossing followed a similar routine. The ship was manoeuvred by tugs through the lock system into the Mersey and alongside the famed pier head. From this tidal floating platform passengers ascended the gangways, in preparation for a 5.30 pm departure. From the mouth of the Mersey she headed north, to another famed river estuary, the Firth of Clyde. Having picked up her Scottish contingent of passengers in tenders off Greenock’s ‘Tail of the Bank’ she rounded the Irish coast on a westward Atlantic track. Five days later she entered the St. Lawrence and made first North American landfall at Quebec. Both physically and symbolically the city and region were tangibly represented by the imposing Chateau Frontenac, a towering French edifice standing proudly on the promontory overlooking the berth where the Empress was moored. After slipping her lines the Empress of Canada then headed upstream meandering against the flow of the St. Lawrence. Eventually the skyline of Montréal emerged from the rugged Canadian landscape and she steamed under the Jacques Cartier Bridge and manoeuvred into her pier, to reach journey’s end.

In November the transatlantic season once again drew to a close. After a brief overhaul Empress of Canada departed on her first cruise from Liverpool, south to the Canary and Cape Verde Islands before returning to Southampton. From the Hampshire port she steamed direct to New York to commence her winter cruise programme. Replicating the previous year she combined West Indies cruises with a long 60 day odyssey to the Eastern Mediterranean. Once again this included extended port stays, dramatic scenery and an intoxicating mix of cultures and cuisine. It would, however be the last, the Caribbean circuit may have been less adventurous but it was well patronised and ultimately more profitable. In April 1963, the Empress of Canada was back at Liverpool embarking on another season on the Atlantic route. However things were changing, the optimism of two years earlier was no longer evident. Perhaps sensing this sea change she was affected by mechanical gremlins on successive September crossings. By the end of the year declining revenues had prompted a competitor, Home Lines, to abandon their Canadian service from Germany (Cuxhaven) via Le Havre and Southampton. Not only did this allow Canadian Pacific a greater proportion of the residual traffic but Home Lines was then building the 27,645grt dual-purpose Oceanic. Had Oceanic entered service as originally planned in 1965, she would have instantly rendered the three Empresses and Cunard’s Saxonia sisters obsolete.

Acknowledging the need to reduce capacity, Canadian Pacific placed Empress of Britain up for sale and on 28th January 1964 she was purchased by the Greek Line. Empress of Canada was by then midway through a series of seven Caribbean cruises from New York. In April she was back on the Montréal service in tandem with Empress of England. Bookings picked up but further economies were deemed necessary. To reduce turnaround times they would no longer utilise the Gladstone Dock. This may in part have been prompted by an unfortunate propensity for striking the lock wall, including her inaugural crossing of the 1965 season. A largely uneventful season was followed by the now annual series of Caribbean itineraries from December through to April. On 12th April she departed Liverpool on the first crossing to Canada for 1966. No doubt the passengers and crew will have been grateful that they were only starting out and not midway through their voyage. On that same day, in mid Atlantic, hurricane force winds and mountainous waves had crushed the forward bulkhead of the Italian liner Michelangelo, killing a crewman and two passengers.

Just over a month later, both Empresses became embroiled in the National Seaman’s Strike, the acrimonious and largely self-destructive industrial dispute that paralysed the entire British merchant marine. For six weeks the fleet lay idle, tethered up in great ports including Southampton, London and of course Liverpool. In truth this was simply the most graphic illustration of a pernicious malaise that infected the workplace in the early 1960s. Unions were essential to curb the exploitation of workers, including crews and dock handlers. Nevertheless on many ships including Empress of Canada, the unions created factions, and a secondary hierarchy which reduced, rather than enhanced, crew morale. Strikes were endemic, often on tenuous grounds and invariably delayed schedules. The resulting disruption further eroded public confidence in sea travel and ultimately accelerated the demise of liner services.

Minor incidents blotted the following year, a brief grounding off St. Juan, a collision with a tender off Greenock and the disturbing spectacle of impaling a whale in mid-Atlantic. Bookings rallied but this was prompted by Cunard’s withdrawal from the Canadian service, rather than a surge in popularity. The Empresses maintained the transatlantic route through 1967 but in 1968 there were strong rumours both would be sold and that Canadian Pacific would withdraw from passenger shipping entirely. In fact the company was still looking at how it could revitalise it’s fortunes. One method was the adoption of a new logo and livery. To the consternation of most the smart buff funnel with red and white checker panel was replaced by a stylised C, formed by a circle and square in shades of green. Compounding the corporate graffiti, the neat green sheer line around the hull was broadened into a wide stripe and CP Ships was emblazoned on her beam. On 23rd November 1968 the new look flagship left Liverpool for New York, via Quebec. In addition to the new livery Canadian Pacific had decided on a new itinerary and the Caribbean cruise programme was extended until early June 1969. On returning to the UK her liner voyages were interspersed with cruises, including a 14 day cruise to the Baltic and voyages to the Mediterranean. Further rationalising on the St. Lawrence service included omitting calls at Quebec on the majority of crossings. In 1970 Greenock was dropped from the schedules, so the 11 day round trips invariably saw Empress of Canada sailing directly from Liverpool and Montréal. With a load factor of over 80% the future looked assured, however the figures betrayed the truth. Canadian Pacific had withdrawn Empress of England in April 1970, so the Empress of Canada was now steaming alone.

Passenger numbers may have been higher but the crew continued to seek every opportunity to disrupt the timetable. Despite repeated assurances that the ship was not for sale and optimistic statements to the contrary, it was evident that the end was near. As if sensing the inevitable, the ship suffered a boiler room fire in August 1971 whilst inbound to Liverpool from Canada. Although quickly brought under control the alarm was sounded and passengers mustered for a possible evacuation. As the St Lawrence season drew to a close, Canadian Pacific finally ended all the speculation and announced on 9th November 1971 that ‘economic circumstances made it impossible to achieve a viable passenger ship operation’. Empress of Canada slipped her moorings on the frigid early morning of 17th November, departing Montréal on her 121st and last Atlantic crossing. She stayed in Liverpool for almost three weeks before steaming down to the Thames and was laid up in a backwater of Tilbury docks. Dispassionately, 80 years of ocean travel by Canadian Pacific’s elegant white Empresses came to an end. After a pathetically short decade in service Empress of Canada awaited her fate.

Salvation came quickly and from a most unexpected source. After a prospective deal with Home Lines failed to materialise the sedentary Empress was viewed by an Israeli shipping executive Ted Arison. Renowned as one of the co-founders of Norwegian Caribbean Lines, Arison was in the UK seeking a ship to set up a new cruise operation. Having discounted two of Cunard’s laid up Saxonia sisters Arison reputedly felt an instant affinity with the former Canadian Pacific flagship. He sought investment from lifelong friend Meshulam Riklis, then the principal shareholder in a Boston-based tour operator, utilising the trading name Carnival. By the end of January he had secured the ship and on 21st February she was renamed Mardi Gras. The pace was unrelenting, Arison’s team immediately started marketing the maiden voyage which was ambitiously scheduled for 4th March 1972. Mardi Gras required only superficial internal refurbishment, to minimise cost and time (and much to the former owner’s displeasure), Carnival cannibalised the existing funnel livery by retaining the basic shapes, whilst changing the green tones to a vivid red, white and blue. A week later than planned, on 11th March the hurriedly prepared vessel steamed out of the port of Miami, down Government Cut, bound for the Caribbean.

Perhaps it was the haste of preparation or simply bad fortune, whatever the reason, a combination of high winds, minimal clearance below her keel and miscommunication on the bridge, led Mardi Gras to run aground. The flagship (only ship!) of the self-publicised ‘Golden Fleet’ was a laughing stock, Norwegian Caribbean Lines mockingly introduced a new cocktail on its rival vessel named ‘Mardi Gras On The Rocks‘!

With tenacity Arison and his team persisted, despite Mardi Gras’ unfortunate baptism and accumulating losses. He was convinced there was an untapped market for the ‘fun ship’ concept. After two years Riklis and his co-investors relinquished their interest in the cruise operation citing the substantial increase in operational costs. The quadrupling of fuel prices in the autumn of 1973 had been the final straw.

Ted Arison acquired the ship and debts for a nominal down payment in November of the following year. Within a month Arison’s faith was repaid. Mardi Gras earned a profit. Within a year she was earning accolades as the best seven day cruise ship in the region. The concept was simple. Historically cruising was perceived as the preserve of the rich and elderly. Carnival started to market their cruise vacations to those jokingly referred to as ‘under the age of death’. Upbeat music echoed throughout, there was fun-based entertainment, an expanded casino, everything in short to augment the Caribbean experience for the under 50s. Crucially, Carnival were actively looking to lure a clientele who would not previously have considered a cruise holiday. Consigning the misguided pretension of ‘The Golden Fleet’ to the marketing waste bin, the ‘Fun Ship’ tag caught on. Word spread rapidly, backing up an intensive TV advertising campaign. Carnival’s fortunes changed course dramatically.

As previously mentioned, after some time most of the cargo handling equipment was removed, otherwise there was little structural change. Internally the lustrous wood panelling was retained although steadily overlaid with a glitzy film of metallic wallpaper. In contrast to rivals NCL and Royal Caribbean Lines (RCL) who had introduced new specialist cruise ships, Mardi Gras looked old-fashioned and even outmoded. Incongruously the restrained and sophisticated Mayfair Lounge, once the preserve of moneyed socialites, was crammed full of one-armed bandits as the Showboat Club Casino. The passenger complement increased but so too did the standard of some accommodation, with some en-suite facilities added to the lower priced, former tourist class accommodation. New cabins were created in former public rooms, including the original first class Salle Fronterac restaurant.

Mardi Gras generally stuck to a seven day circuit, re-visiting some of the ports she had adorned in Canadian Pacific colours, from Miami to San Juan, St. Maarten and St. Thomas. Her success (in 1975 her load factor exceeded 100% based on lower berth occupancy) prompted Arison to look for a suitable running mate. With numerous liners now redundant there was quite a choice but one ship in particular caught his eye. Languishing in Piraeus harbour was Mardi Gras’ near sister Queen Anna Maria, formerly Empress of Britain. Although maintenance had been compromised lately due to the Greek Line’s precarious financial position, they had rebuilt her and made her ideal for a cruising role. Carnival acquired her for $3 million and after a quick refurbishment she entered service on the same seven day itinerary renamed Carnivale.

Carnival’s continued prosperity prompted Arison to acquire another superannuated liner. At 32,697grt, Safmarine’s SA Vaal, formerly Union Castle Line’s Transvaal Castle, represented a further significant leap in size. Unlike Mardi Gras and Carnivale where only superficial changes were implemented before entering service, the new ship would undergo a significant rebuild, with a consequential increase in her passenger complement by converting the extensive cargo holds into new cabins.

Mardi Gras relinquished her position as flagship to the newly christened Festivale, which also took over the mantle of largest cruise ship sailing from Miami. Competitors and industry commentators watched Carnival’s expansion with a mixture of envy and incredulity. Like it or loathe it the Fun Ship formula was bringing tangible success. Mardi Gras also moved to a new itinerary. Departing Miami on Sunday afternoon, she now called at Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic, before steaming to St. Thomas and Nassau en route back to Miami. This year round circuit was however punctuated by occasional ventures further afield. Earlier in her Carnival career she undertook cruises from Baltimore and Norfolk. In August 1979, she made a nostalgic return to Montreal. Accompanied by fireboats and with crowds lining the St. Lawrence, the former Empress of Canada was given a rousing welcome before sailing the same night for Quebec and Boston. A year later she returned and ran two cruises from the Canadian port.

By then Carnival was facing a significant challenge. Prompted no doubt by the success of Festivale, Arison’s former partner and nemesis, Knut Kloster, had purchased the laid-up French Line flagship France and transformed her into the Norway, a cruise ship which physically and metaphorically eclipsed all rival tonnage. Norway’s introduction in June 1980 totally transformed the cruise market. Her size and facilities meant the ship as a destination had arrived, where she sailed was immaterial. With no equivalent second-hand vessels available, Carnival reacted by placing an order for its first new build, emerging in 1981, the Tropicale. Mardi Gras and Carnivale were despatched for major internal refurbishment. The modernisation included the replacement of carpet, curtains and furnishings. Doubtless well intentioned, the 1982 revamp compromised the last vestiges of Canadian Pacific décor. Although Mardi Gras’ popularity showed no sign of waning her itinerary was changed around this time. She sailed to the western shores of the Caribbean, calling at Cozumel in Mexico, Grand Cayman and Ocho Rios.

Tropicale was not a one-off. Carnival’s enviable popularity spawned three more newbuilds by mid-decade, Holiday, Jubilee and Celebration. Twice the tonnage of Tropicale these cruise ships were larger than historic liners like Canberra and Michelangelo. Mardi Gras moved home port, first to Fort Lauderdale, then in 1990 Port Canaveral, running three and four day cruises to Nassau and Freeport in conjunction with Carnivale, the two ships sailing in convoy. By this time Carnival was introducing a new class of 70,000gt vessels, beginning with Fantasy in the first month of the decade. The company was also looking further afield, with sights set on the European and Asian markets. Rumours abounded that Mardi Gras would be repositioned to the Mediterranean in 1993, then a counter rumour that Japan would be her new base.

Amid speculation that Carnival were looking to off-load their pioneering flagship, the company announced later in the year that Mardi Gras was to be renamed Olympic for a new service in the Eastern Mediterranean. Originally planned as a joint venture with Dolphin Cruise Line and Epirotiki, by the end of 1993 plans had changed again. Although transferred to Epirotiki as part of a complex merger agreement, Mardi Gras would not be crossing to Europe. Instead the Greek company had chartered the ship to a new American venture named Gold Star Cruises. Her Carnival career had lasted twice as long as her Canadian Pacific one and forged the largest, most powerful cruise line in the world. Quite a legacy for a ship that had run aground on her maiden voyage.

Despite ambitious statements from Chairman Peter Catalano the prospects of success for Gold Star Cruises seemed remote. Of course such wisdom comes from the unerring benefit of hindsight. Day and night cruises of just a few hours duration were an integral part of the Florida cruise scene. Gold Star however, proposed to sail a 27,000gt liner on these jaunts from Galveston. Appropriately renamed Star of Texas, with a stylised star funnel motif, the former Mardi Gras steamed out of her new Texan homeport on 30th October 1993, bound rather appropriately on a ‘cruise to nowhere’.

Within months Gold Star were in financial difficulties. In a last ditch attempt to revive their ailing fortunes, Star of Texas was rechristened Lucky Star and repositioned to Miami in November 1994. There was to be no reprieve and unable to meet the charter payments, the parent company filed for bankruptcy protection. Lucky Star Cruises ceased operation on 30th December 1994.

With creditors gathering, Epirotiki repossessed their ship and moved her to a lay-up berth at Freeport, Bahamas. Although immaculately maintained by Carnival during their tenure, the former Mardi Gras had deteriorated rapidly. The gambling and nightclub clientele did not help by defacing her fixtures and fittings at will but it was the reckless neglect of the chartering company that needlessly dilapidated the 33 year old ship. Her condition dissuaded potential charters but of equal importance was the prospect of being arrested as soon as she docked at a Florida port.

With no offers forthcoming she sailed from Freeport for the Mediterranean, arriving at Piraeus on 10th May 1995 and joining the rusting, tethered, flotillas of that great port, in purgatorial limbo. She was renamed Apollon. It seemed inevitable that she would join the stream of contemporaries to the scrap yards of north west India. In fact there would be new employment for the veteran cruise ship, involving a nostalgic return to former stamping grounds. In 1997 a package-tour operator Direct Holidays had entered the UK market using the former Costa Line flagship Eugenio Costa, renamed Edinburgh Castle. Uniquely servicing the Scottish and Northern English market, there was such a positive response that the company sought a second vessel. In December 1997, they reached an agreement to charter Apollon after a $20 million refit at the Skaramanga yard. Initial reports suggested that she would be renamed Stirling Castle.

There was a troubled start. With refurbishment incomplete, shipyard personnel were embarked for the delivery voyage from Greece to Liverpool. Boiler damage caused a reduction in speed and then storms off the Iberian peninsular and the notorious Bay of Biscay incapacitated the majority of workmen. She was diverted to Avonmouth, where mechanical repairs and interior refitting were completed.

Direct Cruises encountered a torrid baptism with Edinburgh Castle in particular suffering from electrical gremlins and the vagaries of a negative press. Despite passenger popularity, her owners were in financial difficulties and a major refit at Southampton in the autumn of 1998 turned into an extended incarceration, ultimately the ship being arrested and declared bankrupt in January 1999. Apollon sailed alone in 1999, repeating many of the previous year’s itineraries to the Canaries, North Africa and the Western Mediterranean. There were also two Scandinavian cruises, for the first time in her 38 year career she visited the magnificent Norwegian fjords, North Cape and Spitsbergen, with passengers sampling perpetual day in the ‘Land of the midnight sun’. Then in early July she set course for the Baltic on a 14 day cruise, calling at the Scandinavian capitals of Oslo, Stockholm, Helsinki, Copenhagen but also the spectacular former Russian capital of St. Petersburg. On 9th October, Apollon departed Liverpool on a season finale, 13 nights to Piraeus. She would never return.

With a fine reputation established her future seemed assured, alas corporate politics intervened and Direct Cruises abruptly cancelled the 2000 cruise programme and Apollon’s charter. Laid up in Eleusis Bay, the end seemed inevitable. There would however be a final swansong when owners Royal Olympic placed her on four and five day cruises to the Aegean Islands. Ironically her ‘Tropical White’ hull from Liverpool service was changed to the company’s deep blue for the Mediterranean sunshine. The first cruise departed Piraeus in May 2001 but two months later she was chartered as an accommodation ship for the G8 Summit at Genoa, before resuming her cruise role until mid-August. Initially laid up at Naples she soon joined the tethered death row in Eleusis Bay.

Her condition quickly deteriorated through 2002 and with no serious bidders for preservation in a static role she formed part of a moribund triumvirate of ageing liners that Royal Olympia sold to the highest bidder, Indian breakers.

In November 2003, Apollon departed Greece and ponderously began her journey to the East via Suez. On 4th December 2003, she anchored off the Gujarati Coast, awaiting her turn at the knackers yard. The next day, with a full head of steam she was driven onto the oily sands of Alang. Soon nothing remained of the final White Empress and first of the Fun Ships, except a remarkable legacy.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item