A dream too far

by John Hannavy

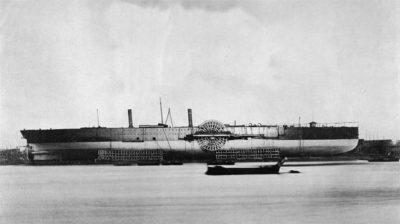

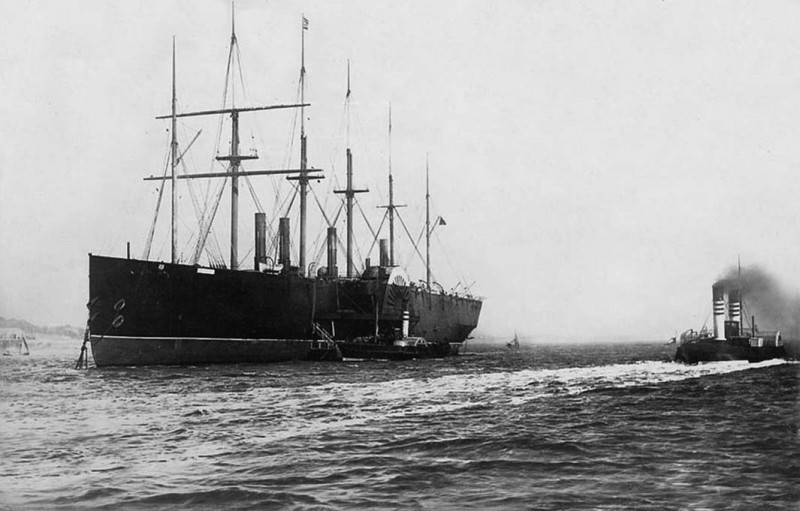

Close to the water’s edge on the north shore of the Thames at Millwall are the last reminders of the largest ship ever built in the Victorian era. The array of wooden posts and beams, uncovered a few years ago during the redevelopment of the riverside, are all that remains of the shipyard from where Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s SS great Eastern was launched.

It should have been a momentous occasion on 3rd November 1857 when, with a crowd of many thousands watching, and a photographer lined up to take an historic picture as the biggest ship in the world slid sideways into the river Thames at 12.30 pm when Henrietta Hope, the daughter of one of the major investors in the vessel, christened her Leviathan. That was much to the surprise of everyone, including Brunel, as it had been widely expected that she would be named great Eastern. Indeed her name was eventually changed to great Eastern in July 1858.

But it was not just her naming which failed to go according to expectations. The great ship refused to move more than a few feet, the stern moved four, the bows three, and despite a complex system of steam winches and hydraulic rams, Leviathan thereafter stayed firmly rooted to her slipway. And to make matters worse, a labourer lost his life when crushed by one of the steam winches designed to help move the vessel towards the water.

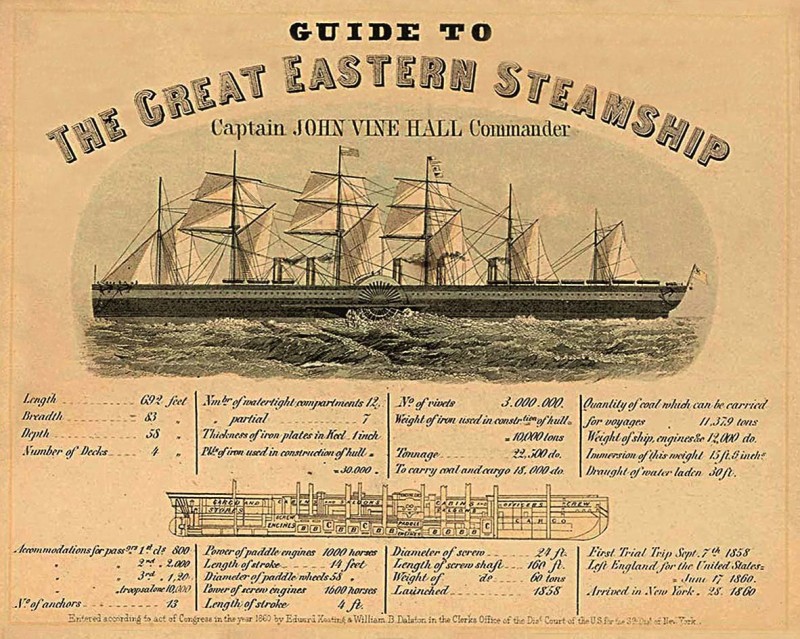

At 18,915grt and nearly seven hundred feet long, she was not just the biggest ship ever built in the 19th century, she was several times larger than anything planned before.

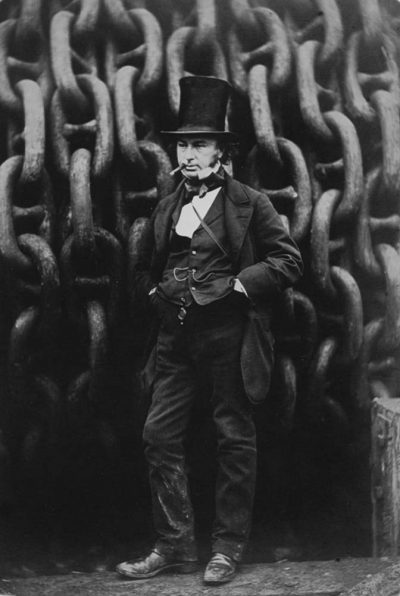

Photographer Robert Howlett exhibited his views of the great ship at the Exhibition of the Photographic Society in February-March 1858, just a few weeks after Leviathan was eventually floated on 31st January 1858. One of those exhibited was titled simply ‘Portrait of I.K.Brunel Esq.’ The portrait which has become one of Victorian photography’s iconic images, now usually known as ‘Isambard Kingdom Brunel standing before the launch chains of the great Eastern’. The launch chains had been intended to slow down the vessel’s journey towards the river, but on that November day they remained fully wound on their huge wooden drums, their role postponed for another day.

The ship was to be built at the yard of John Scott Russell & Company at Millwall but it was quickly realised that the yard would never be able to accommodate a ship of such a size. Russell elected to lease the nearby Napier Yard, but that decision, and Napier’s location on the river would impact on just about every aspect of the ship’s construction.

Everything about the ship stretched engineering know-how to its limits. Too big to be launched stern first into the narrow river, Brunel and Russell had to devise and construct a special launch ramp to allow the ship to slip into the river sideways, but due to some errors in the construction of that ramp – too gentle a slope, and a slight rise towards the middle of its length, together with the sheer deadweight of the vessel itself, the crowd on 3rd November 1857 went away disappointed.

The failed launch was just one in a series of problems which had beset Brunel’s grandest and final project. Her keel had been laid on 1st May 1854, with a scheduled construction time of three and a half years, but by early in 1856, Russell’s company was in dire financial difficulties, and to save the project from collapse, a consortium including the Eastern Steam Navigation Company had to take over the management of the project.

Folklore has it that during her construction, two riveters mysteriously vanished, and stories persisted that they had accidentally been sealed into the ship’s revolutionary double-skinned hull!

The great Eastern was very much a hybrid, driven by both a propeller and paddle wheels, together with an estimated 58,000 sq.ft. of canvas hung from six masts. Large steam engines amidships drove the 56ft diameter paddle wheels, while another, further aft, powered the 24ft four-blade screw. To raise steam for them all there were ten massive boilers, and to fuel their furnaces, she carried 12,000 tons of coal. Balancing the output of the two propulsion systems once the vessel was underway cannot have been easy.

Thus, she was originally built with five tall funnels, but despite several contemporary illustrations showing her underway, smoke streaming from all five, and a massive area of sail deployed, that was never the case. It was found that sails could not be used in conjunction with the paddles or screw, except on the first two masts, as the exhaust from the boiler furnaces would have set them alight!

Brunel’s vision had been for a ship which could sail to Australia and back without refuelling. Coal had yet to be discovered in Australia and he believed that there were significant economies of scale if he built a ship capable of carrying the same passenger load as several smaller ones. In that respect, he was quickly proved wrong, or ahead of his time, and as a passenger ship she was a commercial failure. But he would not live to learn that, dying on 15th September 1859 at the age of just 53. He had collapsed with a stroke on board great Eastern on 9th September, and it is said that being told a few days later of an explosion on board during her sea trials which had killed a number of her crew was what finally caused his demise. His dream of a triumphant entrance into New York harbour on board the biggest ship in the world, and the engineering marvel of the day, would never be realised.

On her maiden voyage to America, fewer than 200 of her 4,000 passenger berths had been taken up, and even on her most successful Atlantic crossing, she was only a little over half full. Achieving the economics of scale which Brunel had envisaged were, of course, only possible if she was substantially full. As a temporary tourist attraction in New York harbour, she attracted many times the number of people who had travelled on her and that statistic was repeated wherever she went. Brunel’s vision of huge passenger liners was simply half a century ahead of its time.

Had there been no further use for her, great Eastern might have been scrapped after just a few years but her size, her massive carrying capacity, and her motive power combined to make her ideal for an important international role.

Using both propeller and paddle drive, she was a very stable ship, and with her revolutionary double hull, a very safe one. Indeed during her life she survived a greater tear in her hull plating than that which would sink the Titanic almost half a century later.

But it was her sheer size which made her an obvious choice to undergo conversion for use as a cable-laying ship. With funnel No.4 and two of her boilers removed, her passenger accommodation stripped out and replaced by three huge ‘cable tanks’, the heavily modified ship eventually successfully laid the second transatlantic telegraph cable in 1865-6, and several other cables thereafter.

No other ship in the world had the capacity to carry the 2,600 mile long cable. She had finally found a role which she could undertake profitably, and was used to lay cables across the Indian Ocean as well as the Atlantic.

After her cable-laying duties came to an end, the ship was sold to an entrepreneur who planned to refit her and operate her as a liner once more, but profits again proved elusive, and by the early 1880s, it was clear her useful days were effectively over.

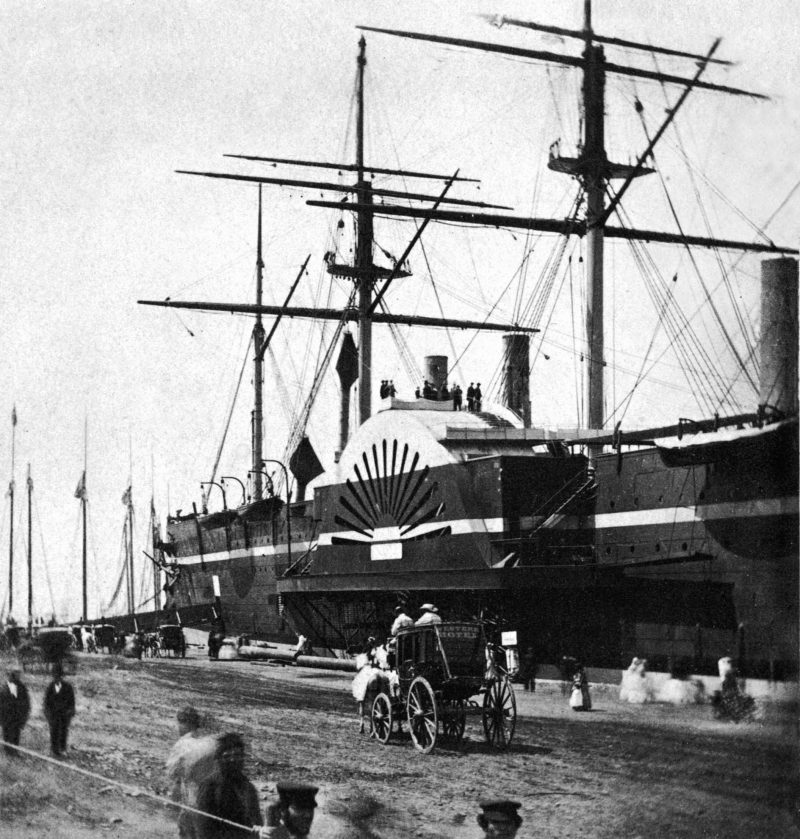

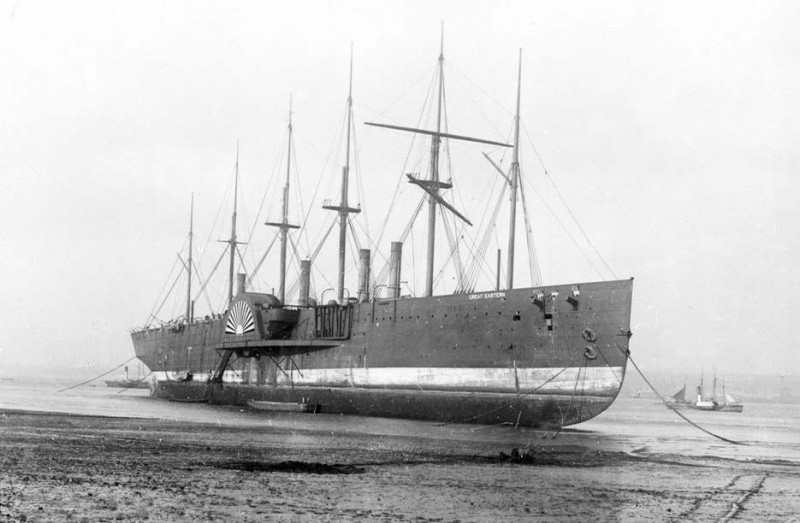

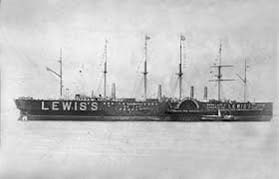

In 1885, she was leased to the owner of Lewis’s department store in Liverpool, and moored in the Mersey with an advertisement for the shop painted along her side (above), and an exhibition in the main public areas, a somewhat ignominious end for such a revolutionary ship. Lewis’s also had stores in Dublin and Glasgow at that time, so the SS great Eastern also did tours of duty off both those ports, but by 1888 her fate was sealed. As The New York Times reported on 8th September 1888, under the headline ‘Great Eastern Beached’. The Times in London reported:

“The steamship great Eastern, which has passed through so many vicissitudes since her launch 30 years ago, was successfully beached near New-Ferry on the Cheshire shore of the Mersey on Saturday. Since last December, when she became the property of Messrs. Henry Bath & Co. of Liverpool, the great Eastern had been moored in the Clyde between Helensburg [sic!] and Greenock, and in the inspection which she has undergone, unexpected value is said to have been discovered. Last Wednesday at noon she was got under way, and started on what is intended to be her last voyage. With her own steam she could make a speed of four to five knots, but she was towed by the powerful steam tug Stormcock. The weather was bright when the vessel started, but next morning the wind freshened, while dark masses of clouds presaged the dirty weather that followed.

The storm they met off the Isle of Man meant that the tug had to cast the big vessel adrift for a time, but as the gales abated, the hawser was reconnected and she continued her journey towards the Mersey. After an account of her travails en route, the report ended in a somewhat more positive vein than might have been expected, offering a glimmer of hope.

The great Eastern now lies about 200 yards to the southward of the New-Ferry stage. It is said that the ship will now be broken up and the material sold, but there are persons who believe that some use will yet be found for the vessel designed by Brunel.”

It was a false hope, and she was eventually broken up on the beach at rock Ferry, where, a century and a quarter later, fragments of her hull plating and rivets are still periodically revealed after heavy tides. Her mainmast was saved and still stands at the Kop-end of Liverpool FC’s Anfield stadium, and a damaged section of one of her funnels is at Bristol, part of the SS Great Britain Museum.

So strongly was she built, that it took 200 men nearly two years to break her up. Long before her demise, screw-driven steamers had proved their worth both in terms of ease of steering, and ability to cope with heavy seas and at higher speeds their smooth motion improved passenger comfort.

It would be nearly fifty years before anyone attempted to design a ship as large as her again, by which time paddles would not even enter their thinking. White Star Line’s RMS Oceanic launched in 1899 was four feet longer, and their 1901 SS Celtic, at 20,904grt, was just a little bigger.

Paddle steamers would, however, continue to be constructed in large numbers in British yards until the outbreak of the Second World War, but they were all pleasure steamers. A few more were built in the post-war years, notably PS Waverley, and the last large British paddler to come off the stocks was the Loch Lomond pleasure steamer PS Maid of the Loch, 95 years after the launch of the great Eastern. Efforts to return Maid of the Loch to steam will continue for several years yet.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item