The French Line’s Luxury Liner

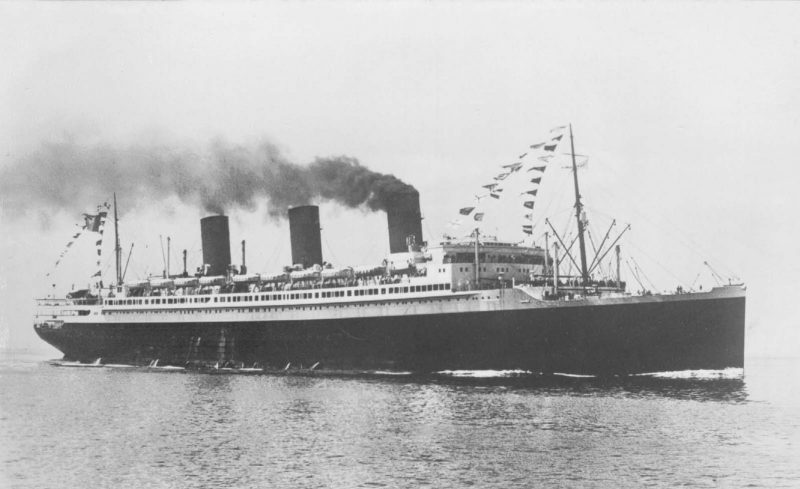

This famous French transatlantic liner had a long career of over thirty years from her completion in May 1927. She was launched on 14th March 1926 at the Penhoet yard of Chantiers de l’Atlantique at St. Nazaire as the largest French ship yet built at 43,153 grt with a length of 791 feet and a breadth of 92 feet. She was named after the region of France around Paris that dated back to 1387 and which today borders Picardy, Champagne, Normandy and Orleanais. She was completed with superb accommodation for 537 first class, 603 cabin class and 641 third class passengers and a crew of 646 with a garage for 60 cars. Her four powerful Parsons steam turbines, two triple reduction geared and two double reduction geared, produced 60,000 shp and drove quadruple screws to give her a service speed on the Transatlantic route of French Line to New York of 24 knots. She was neither the largest nor the fastest ship on the North Atlantic, but she was considered the most beautiful French Line ship, inside and outside, until the advent of the fabulous Normandie in May 1935. She had six passenger decks and three funnels, and ran alongside the three funnelled Paris of 1921 and the four funnelled France of 1912. She regularly carried a higher percentage of first class passengers than any other liner, and was thus the leading North Atlantic liner for her affluent and fashionable American and French clientele.

Ile de France was renowned as much for her Art Deco styling of her public rooms as for her external appearance. The Grand Foyer, similar to the atriums of modern day cruise ships, was an impressive four decks high. Her superb First Class Grand Dining Room towered three decks in height, and this vast space was lit by hundreds of square light panels arranged in rows along the roof and sides, and had a spectacular staircase as a main entrance. The First Class Main Lounge featured art deco chairs and tables and a very large, idyllic wall mural of ceiling height and width of 25 feet, with the room lit by large lamps placed inside a dozen urns at table height around the walls. The bar in this lounge was the ‘longest afloat’, where Americans, her dominant clientele, could flout Prohibition, drinking whisky at 15 cents a glass. The dance floor in the Salon de Conversation measured 516 square yards, and the liner was also fitted with a complete Parisian sidewalk café with awnings above. In the children’s playroom, there was a real carousel with painted ponies, which rotated accompanied by jolly music. The liner had a full sized tennis court, and a gymnasium, and her greater deck space and gravity davits for her lifeboats were new features. The dazzling entrances to all of her public rooms allowed Hollywood film stars, duchesses, dowagers and all of her female passengers to stand at the entrance to be appreciated with admiring glances from those already in the room.

All cabins, including those in Third Class, had beds instead of bunks. French Line decided that all of her First Class cabins would be different from each other, and also added four apartments of great luxury and ten of modest luxury. The First Class cabins usually had windows instead of portholes, separate bedrooms and possibly a sitting or drawing room, trunk room, dressing room, entrance foyer and adjoining servant’s quarters. They were decorated in many different styles, all with veneer panelling, which unfortunately creaked due to her engine vibration until they were padded and refixed in 1933. The First Class accommodation could thus rightly claim to be the finest seen at sea, and the ship was well decorated with statues by Baudry and Dejean, bas-reliefs by Jeanniot, Bouchard and Saupique, enamel panels by Schmied, artistic ironwork by Subes and Szabo, paintings by Docos de Ia Haille, Genez and Balande, and her chapel in the Gothic style had a fabulous wooden Stations of the Cross piece by Le Bourgeois.

The overall style of the ship was based on the art deco themes of the 1925 Paris Exposition des Arts Decoratfs et Industriels Modernes. This exhibition marked the highpoint of France’s creativity in the decorative arts and was held from April to November of that year. It was staged as a demonstration of France’s economic recovery, and the city of Paris was used to promote French luxury goods from stores such as Bon Marche and Printemps as well as French design. The pavilions and shops of the exhibition presented Paris as a veritable ‘yule lumiere’ with lavish lighting along the Seine complete with fountains and dazzling window displays, fashion shows, dance spectacles and other events from the world of fashion, art and performance. The exhibition was laid out along the banks of the Seine between the Grand Palais and the Esplanade des Invalides as a central site similar to the earlier World Fairs held in the city. The emphasis of the exhibition was on luxury French goods with French Line represented by its many posters in the pavilions.

On her completion on 29th May 1927 it was decided, because of her deep draught, to move her out of the tidal basin at St. Nazaire at high tide at 1400 hours, and the lock gates were opened. When the ropes were cast off the mainmast was adjacent to a dockside crane and the engine telegraph put ‘slow ahead’ to ease her away from a collision with it. The ship missed the crane and, to stop her, ‘reverse engines’ was ordered. However, the engine room control jammed and the ship continued forging ahead towards the lock gates. The Captain aimed the ship at the centre of the exit from the basin as being the least dangerous course. Unfortunately, the drawbridge across the exit was still in position and a crashing demolition course was imminent. Miraculously, the man in charge of the drawbridge saw the charging ship moving at seven knots, and opened it, with only feet to spare, just in time for the new liner, unaided by her attendant tugs, to steam through the lock into the estuary, where control of the ship was regained. Ile de France made a brief stop in Brest, and then sailed to Le Havre, her home port, where she arrived on 5th June, and from where she sailed on her maiden voyage to New York on 22nd June with a brief call off Plymouth for passengers ferried out by tender.

French Line ended the financial year of 1928 with record earnings in excess of a billion francs due to the contribution of the fabulous new liner. In July 1928 under Capt. Joseph Blancart, she pioneered the fastest mail system between Europe and New York by installing a catapult at her stern for trials using two CAMS37 flying boats that took off when the ship was within 500 miles of New York or Le Havre, and which cut the mail delivery time by one day. However, this was very expensive and in October 1930 the catapult was removed, ship to shore telephones having made the concept redundant. Ile de France was popular with passengers right through the Depression years, averaging an occupancy rate of over 50%, and her popularity was such that by 1935 she had carried more first class passengers than any other transatlantic liner. In November 1931 a six month overhaul began which altered her tonnage to 43,450 grt with accommodation then for 670 first class, 408 second class, and 508 tourist class.

In January 1935, she became the first French Line ship to call at Southampton with an outward call instead of Plymouth after leaving Le Havre. In May of that year, she was joined by the new superliner Normandie, and with three fabulous ships including the Paris, French Line could claim to have the largest, fastest and most luxurious ships on the North Atlantic. In May 1937 she made a special ‘Coronation sailing’ from New York to Southampton for the coronation of King George VI. Unfortunately, two major events shattered the prosperity of French Line, the first being the loss of Paris on 18th April 1939 when she was destroyed by fire whilst docked at Le Havre, and the second was the invasion of the Nazis into Poland on 1st September 1939 to begin a war from which French Line passenger traffic never really recovered to pre-war levels.

On the outbreak of war, Ile de France was berthed at Pier 88 in New York, opposite Normandie. French Line did not wish to send their great liners back to an uncertain future in their homeland, and Ile de France was then towed by ten tugs to a berth on Staten Island and laid up. In March 1940 she was chartered to the British Government and she sailed on 1st May for Marseilles, painted drab grey and carrying war munitions. She then sailed one month later for Indo-China but with the fall of France she was diverted to Singapore, where she was formally taken over by the British Government. She arrived back in New York in the autumn of 1940 to be converted to a troopship by Todd Shipyards during a four month refit that included dormitories for 9,700 troops plus new galleys, toilets and plumbing systems. She was then put under P. & O. management with an Asiatic crew and trooped from bases in Saigon and Bombay. She also ran from Cape Town to Suez as a fast troopship out of convoy in the company of liners of similar size e.g. Mauretania and Nieuw Amsterdam, until she returned in 1943 to the North Atlantic under Cunard Line management to move American troops to Europe in company with her chummy French ship, Pasteur completed in 1939.

Ile de France ended her troopship service in September 1945, and after a quick refit was sent on repatriation voyages from Cherbourg to Canada, New York and French Indo-China. Finally, in the Spring of 1947, she was handed back to French Line and sent back to the yard of her birth at St. Nazaire for a two year refit. This included the removal of her third dummy funnel, and the replacing of the other two by wider, modern internally braced funnels. The black part of her hull was swept upwards almost to the top of her stem to give her a more curved and speedier appearance. She now had accommodation for 541 first class, 577 cabin class and 227 in tourist class and her tonnage was 44,356 grt. On 21st July 1949, she resumed her Le Havre to New York service and was joined in August 1950 in a three ship French Line service by the converted Liberte ex Europa and the veteran De Grasse of 1924, which had single handedly operated the French Line transatlantic service since 1947. The pairing of Ile de France with Liberte enabled French Line post war passengers to enjoy the delights of the pre war era, especially the art deco features of the ‘Fabulous Tie’. On 20th September 1953, Ile de France rescued the crew of the sinking Liberian cargo ship Greenville. De Grasse was sold in March 1953 to Canadian Pacific Line and renamed Empress of Australia, and Ile de France under Capt. Paul Kerharo and Liberte then operated together on their six day Atlantic crossings.

On July 1956, lIe de France was one of four ships near to the location off Nantucket where the outbound Stockholm had collided with the inbound Andrea Doria and she rescued 753 survivors. A total of 1,663 lives were saved in the six hour operation, although 47 people lost their lives from the Andrea Doria and five lives were lost on Stockholm. In February 1957 the ‘Ile’ ran aground on a reef at Martinique while cruising, and her underwater damage was repaired in dry dock at Newport News, after being refloated and towed there by an ocean going tug. On arrival back at Le Havre in late November 1958 after her last Transatlantic voyage, she was laid up as French Line had decided, in view of her age and the changing pattern of Transatlantic travel, her economic life was over. She was then put up for sale, and a variety of offers poured in, including a rather ridiculous idea to sail her up the Seine to the French capital in Paris after her masts and funnels had been removed. On 11th December 1958 she was sold to Yamamoto K.K. of Osaka for scrapping and departed from Le Havre on 26th February 1959 for Osaka, watched by a large crowd of well-wishers as Furanzu (France) Maru.

A final twist in the saga of this great liner was then to unfold. The Japanese scrap company chartered the ship to a Hollywood film company for use in the film ‘The Last Voyage’ and she was renamed Claridon (above). Despite legal action by French Line, the disaster movie went ahead and was based on the last voyage of a Transpacific liner.

After arrival at Osaka on 9th April, she was towed out and positioned in the middle of the Inland Sea of Japan, and was carefully scuttled in shallow water on an even keel (above), then raised and towed back to Osaka and had been reduced to a pile of rusting shell plating by the end of 1959. Thus ended the 32 year career of a great French liner that had greatly influenced the style and glamour of Atlantic crossings and rightly earned her memorable place in maritime history. Her fabulous art deco public rooms had been damaged by the explosives used in the scuttling and the toppling of one of her funnels, and were then destroyed during the scrapping, a great shame.

At the time of her scrapping, the fabulous and luxurious ‘Ile’ was the fifth largest liner in the world, after Queen Elizabeth, Queen Mary, United States and Liberte, as well as being the only big liner left afloat with a graceful counter stern. Liberte continued her French Line sailings until she made her final departure from Le Havre to New York on 21st November 1961, replaced by the new and last French Line transatlantic liner, the much loved France, which was finally broken up in India in 2008. In January 2009, the last remains of a French Line transatlantic luxury liner were lying in piles of rusting shell plating on an Indian beach.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item