Few place names conjure images as evocative as the Dutch East Indies, the string of islands that now constitute the Republic of Indonesia. The Netherlands’ tenuous hold on this land (only in the 20th century did they gain anything approaching full control), initially through the famous East India Trading Company and later by direct colonial rule, was facilitated from 1870 by two new steamship lines. The first of these was based in the Dutch capital, Amsterdam and called Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland, although it was universally known as Nederland Line.

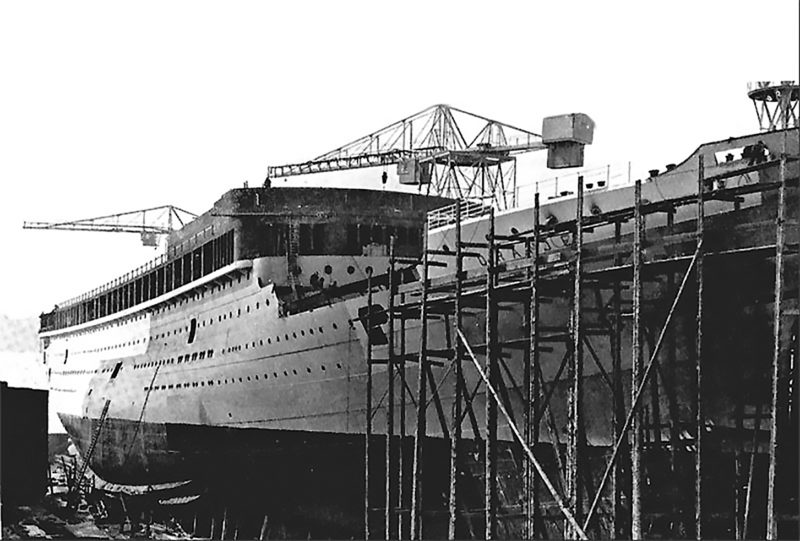

Sixty seven years after the company’s inception, work began on a new flagship. When the first keel plates were ceremonially laid on the stocks of slipway number three at Nederlandsche Scheepsbouw Maatschappij (NSM) on 2nd July 1937 it signalled both a significant investment for the owner and a revival of the yard’s fortunes. NSM had struggled since the onset of the depression, but as orders built up there was renewed optimism and a burgeoning workforce. That confidence took tangible form with Oranje, then known simply as yard number 270.

Fourteen months after the keel laying Queen Wilhelmina arrived at the NSM yard on the banks of the IJ waterway, having travelled by royal barge, to perform another ceremony and bestow the royal house’s name on the new liner. To the embarrassment of shipyard management, once the celebratory Champagne smashed across her bows the newly christened Oranje stayed firmly on the slipway. That garlanded hull remained obstinately fixed in position for over an hour until finally released into her element by the application of hydraulic rams.

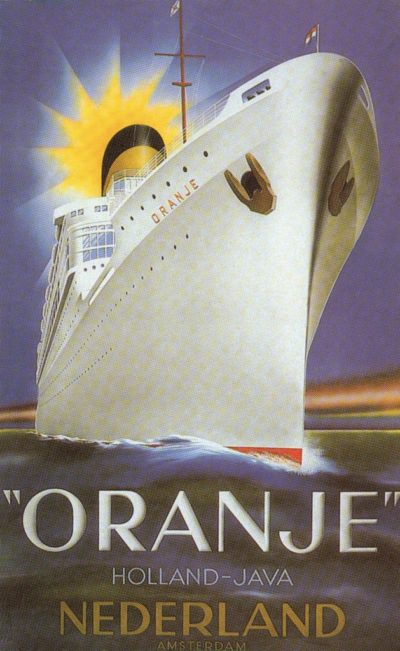

The new liner represented the second instalment of Nederland Line’s rebuilding programme, adding to the incumbent 19,787grt flagship Johan Van Oldenbarnevelt which had entered service in May 1930 as the largest Dutch passenger liner to date. The hull that belatedly slid into the IJ on that late summer afternoon was of a quite unique and extraordinary shape. Utterly conventional from abeam she had a gently raked, flared bow and a neatly curved spoon stern. The subtlety of these features was totally eclipsed by the head on view which revealed the most exaggerated tumblehome of any twentieth century passenger ship. Like some 18th century man-o’-war the new ship’s beam was a full 5m (about 17ft) broader at the waterline than where the hull and superstructure converged, a feature conceived by the shipyard’s chief designer Huibert Prins to resolve a seemingly impossible set of conflicting priorities from the shipping line. The new vessel’s overall draft and beam at main deck level needed to match existing tonnage in order to permit access to shallow East Indian ports and maintain the same Suez Canal toll rate charges respectively. However Nederland Line also wanted a higher service speed, allowing passage from Amsterdam to Batavia in three weeks. This would necessitate larger, heavier and more powerful machinery as well as an increased fuel load. Prins’s unique compromise solution ultimately met all these demands, whilst also providing the requisite stability and speed.

Fitting out the new liner took a further nine months. The completed ship had a handsome profile topped by a lofty, centrally placed tapering funnel. Perhaps the only oddity was that the tall foremast and booms had no balancing mainmast, instead cranes proliferated on the tiered aft decks to service the associated cargo hatches. On her flanks the pale grey hull and open promenades betrayed her tropical itinerary.

There were eight passenger decks, ranging from the lofty Boat Deck, adjacent to the funnel, all the way down to D Deck. Acres of open and sheltered promenades and sunbathing space included an outdoor swimming pool on Sports deck. Standard vertical class divisions applied, with First class forward and centre, Second class heading aft and Third/Fourth crammed into the stern. The principle public rooms for First and Second class passengers (each had a smoking and lounge/music room) were situated on Promenade Deck, the top tier also enjoyed the forward Veranda with its tall windows affording a 270 degree view over the bow and flanks. Restaurants for all classes (Fourth shared Third’s public rooms) were low down on C deck served by a centrally placed main galley.

Responsibility for the interior décor was entrusted to a team of over forty artists, co-ordinated by the veteran artist and designer Carel Adolph Lion Cachet (1864-1945). Lion Cachet (he added the feline surname in 1901) had built a glowing portfolio over the years which included several passenger ship commissions, notably every Nederland Line vessel since 1906. For this, his last shipboard work, he adopted an unapologetically royal theme. Oranje was festooned with articles paying homage to the house after which she was named, although there were also references to her Indonesian destination, including three beautiful panels depicting indigenous tribesmen in the first class dining room.

In June 1939 Oranje departed for sea trials in the North Sea. With shipyard engineers and SMN colleagues in attendance the ship’s three, two stroke Winterthur Sulzer diesel engines were each taken up to their maximum 12,500hp output. Oranje attained a top speed of 26.3 knots, a full four knots higher than her contracted service speed and earning her accolades as the fastest motor liner afloat. Prins’s hull configuration was fully vindicated but unfortunately he was unable to enjoy the moment, having passed away the previous month at just 51 years of age.

To a backdrop of rising tension the Nederland Line took delivery of their new flagship on 15th July and she departed Amsterdam on 4th August 1939, on the first of two ten day cruises to Madeira and the Azores. Having returned from the second cruise Oranje was provisioned and prepared for a maiden voyage to Batavia (Djakarta). However the world and her place in it was about to change dramatically. There was an inevitably subdued atmosphere on board as she slipped her moorings on 4th September 1939 (the day after Britain and France declared war on Germany), and sailed east, via the Cape of Good Hope rather than the conventional route through the Suez Canal. In spite of the considerable detour Oranje arrived in Singapore on 1st October, after calls at Colombo, Sabang, and Belwan-Deli, a day earlier than originally planned, leaving at 5pm the same afternoon with 550 passengers on the final leg to Batavia. It has been estimated that she averaged in the region of 24 to 25 knots on that maiden voyage.

Even whilst Oranje was in the Far East the situation in Europe deteriorated. On her homeward voyage in November passengers disembarked at Lisbon due to increased naval activity in the North Sea and perhaps inevitably her subsequent liner voyage to Batavia would be her last for six long years. After reaching her eastern terminus on 6th December 1939, Oranje was laid up at Sourabaya for safekeeping, alongside fleet mate Marnix van Saint Aldegonde and Royal Rotterdam Lloyd’s Dempo.

Oranje remained in that distant anchorage for over a year. On 10th May 1940 simultaneous attacks on neutral Belgium and the Netherlands finally put paid to the deceptive lull of the ‘phony war’. Four days after the invasion the Luftwaffe laid waste to Rotterdam, killing around 900 and destroying 25,000 homes. The following day the Netherlands surrendered to avoid further civilian casualties.

The bullish Queen Wilhelmina, whom Winston Churchill caustically referred to as “the only man in the Dutch government”, escaped to London on board a British destroyer early in the campaign and established a ‘government in exile’ for the duration of the war. Meanwhile the Germans imposed their own civilian administration which ordered Oranje’s master Captain B. J. Potjer to return his ship to Europe and surrender her as a war prize. Unsurprisingly he refused. With their homeland now occupied Dutch attention shifted to overseas territories and ultimately considered the fate of the passenger ships moored in distant Sourabaya.

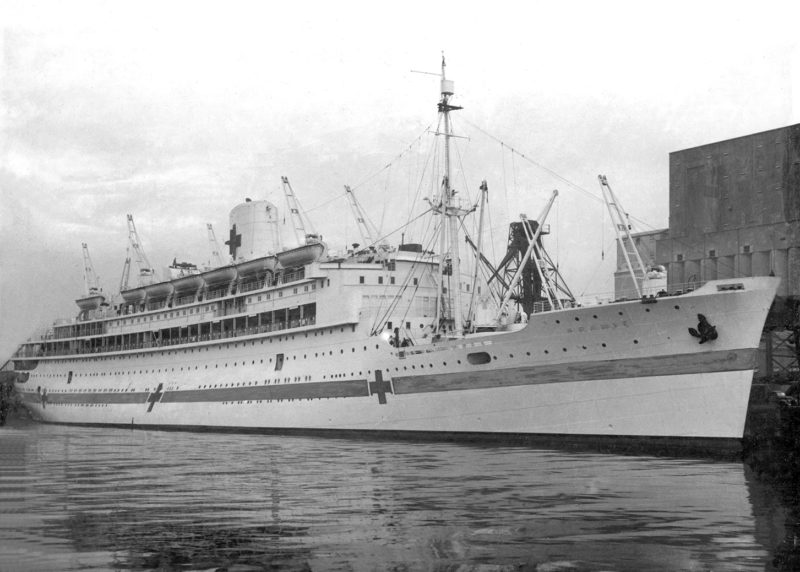

After due consideration, on 10th February 1941 the exiled Dutch government approached their counterparts in Australia and New Zealand with a proposition. They offered Oranje for the role of hospital ship also agreeing to meet the £150,000 conversion cost and similar value annual maintenance subsidies. It was a generous gesture that the hard-pressed Antipodes authorities readily accepted. Over the course of the following month she was inspected by a variety of medical and engineering personnel who assessed what changes were required and determined the location of key facilities. Initial preparations were carried out at Batavia but in late March she sailed under the command of Captain Potjer to the Cockatoo yard in Sydney for conversion.

Three months later on 28th June 1941, Oranje was handed over to the allied cause by a proud Major-General Ter Poorten, in the presence of Australian Prime-Minister Robert G. Menzies. Externally the SMN flagship now bore the all-white livery of the International Red Cross, those sharply sloping hull flanks were emblazoned with large red crosses linked by a broad green stripe. The sides of her freshly painted white funnel had prominent red crosses augmented by a central illuminated cross. In a world plunged into blackout darkness Oranje became a welcome beacon of light.

Internally she was transformed into a state of the art military hospital, capable of accommodating up to 750 sick and wounded patients. Facilities included sixteen wards of single and two-tier cot beds and a large dispensing chemist. There were new lift facilities capable of carrying stretchers, a dental surgery and a fully equipped surgical theatre, the latter located on the largely vibration free Promenade deck. Some first class cabins with air-conditioning were retained and refurbished for treating the most serious cases.

Under the agreement reached between the Netherland’s Consul-General and senior representatives of the Australian and New Zealand armed forces in April 1941, Dutch officers and deck crew, including one hundred Javanese were retained and the ship maintained Dutch registry. The predominantly Dutch medical staff were supplemented by Australian and New Zealand representatives, all under the ultimate control of an ‘Officer Commanding Troops’ (OC Troops) directly selected by the Netherlands government. A Dutch matron supervised all the nursing staff.

Following completion of the conversion Oranje awaited her first assignment. It wasn’t long in coming. On 2nd July 1941 she departed Sydney for Batavia, to embark the Dutch medical contingent before heading west, across the Indian Ocean bound for Egypt. Oranje had been designated the task of picking up and repatriating 630 wounded Australian and New Zealand soldiers from the battlefields of North Africa. Through the ‘usual’ diplomatic channels in Stockholm Dutch officials advised their German counterparts of Oranje’s voyage but it was held up at Aden pending acknowledgement and agreement of her hospital ship status. The ensuing miscommunication led to a (thankfully) unsuccessful torpedo bomber attack.

Due to the Batavia detour and diplomatic delays it wasn’t until 6th August, more than a month after leaving Sydney that Oranje’s first batch of wounded were embarked at Suez. In contrast her return to Australia (initially Perth, followed by Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney) took a mere eleven days and eighteen hours, the first evidence that her speed would prove to be a significant asset in forthcoming years. From Sydney she continued on to New Zealand, where a ceremonial welcome awaited her in the city of Wellington in early September.

That first voyage proved Oranje’s credentials as the largest and fastest hospital ship afloat. In addition to her speed the advanced water distillation equipment and large bunker capacity allowed her to sail on long voyages without the need for provisioning en route. Her size and facilities allowed a broad mix of physical and psychiatric ailments to be treated, making her the most adaptable hospital ship in the fleet and unsurprisingly these repatriation voyages would endear Oranje to the soldiers and their loved ones. The latter lined the piers and terminals to welcome their heroes home. Nevertheless that first voyage also highlighted the language, temperament and procedural differences between the participating nations. It would become a recurring issue throughout the war. She returned to Egypt in November and embarked more casualties, discharging the majority of Dutch medical personnel along with their charges when she arrived back in Australia. The Netherlands had declared war on Japan in the aftermath of Pearl Harbour and now required their doctors and nurses to treat their own troops.

During 1942 the original Dutch OC Troops and matron were retained with a handful of their compatriots, whilst the majority were replaced by Australian and Kiwi doctors and nurses in broadly equal numbers. The tripartite arrangement became increasingly strained during the year but despite the politics the wounded continued to receive excellent care and attention throughout.

In 1943 there was a wholesale withdrawal of Australian troops from the North African theatre in order to bolster the allied effort in South East Asia and the Pacific. As a result Australian medical personnel now left Oranje to be replaced by a British contingent. By late 1943 the medical complement constituted twelve Dutch, forty four British and seventy six New Zealanders. Unfortunately this change appears to have exacerbated rather than resolve the organisational problems. Matters deteriorated to a point where the New Zealand authorities intended to withdraw their personnel, a decision subsequently revoked after a request from the British War Office.

Early in 1944 Oranje received a refit in Durban which reconfigured some of the wards, increasing capacity to 870 casualties. She was absorbed into the British pool of hospital ships under direct supervision of the War Office and primarily assigned to a Naples-Liverpool shuttle service, taking just four days in each direction. Her speed was a huge bonus but a logistical headache for the staff involved. Inbound to the UK they would nurse and prepare the casualties for onward transfer, then after a twenty four hour turnaround sailed for the Med. Although there were no patients the medics were equally busy on the south bound leg, sterilising wards and laundering all bed linen in preparation for the next consignment. Sometimes she also sailed to East Africa (Mombasa and Durban).

Perhaps the most emotive of Oranje’s hospital ship voyages came at the end of the war, repatriating former POW’s picked up at Italian and Indian sub-continent ports.

These voyages continued in earnest after VJ-Day, primarily from Singapore back to Australia and New Zealand. On 23rd September she arrived in Darwin mobbed by celebratory Liberator and Catalina aircraft with 760 former POW’s on board. Arriving at Sydney on 28th September 1945, 637 returnees disembarked into a cavalcade of fifty five ambulances and a fleet of double decker buses. Cheering crowds lined the streets to the Concord Military Hospital in a huge outpouring of emotion.

In contrast to these heart-warming scenes a very different narrative was playing out in the former Dutch East Indies, where famine and disease were impacting on the recently liberated population (including all Dutch nationals who had been interned by the occupying Japanese), against the confused backdrop of a power vacuum and nascent independence movement. In August 1945 nationalist leaders Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta declared Indonesian independence and there ensued a chaotic period of near anarchy referred to as the Bersiap, in which youthful vigilante groups exacted violence on the local Dutch and their helpers. As the international community watched and waited Oranje was initially prevented from sailing to her countrymen’s assistance, however following a refit at Melbourne in early October she departed later that month for Batavia via Fremantle, loading over a thousand former internees (mainly women and children) at Bandoeng and Tandjong Priok because of local unrest and the poor state of facilities in Batavia itself. After return trips to Australia Oranje boarded a first contingent bound for Europe, arriving in Rotterdam with 1,273 passengers on 5th January 1946.

Over the course of the next seven months Oranje shuttled back and forth between Southampton, Rotterdam and Batavia, initially under the management of the Dutch government (the Royal Australian Navy relinquished control in January) then by her owners from March. She finally returned to Amsterdam on 19th July 1946, the first large ship to transit the rebuilt Ijmuiden locks, having carried some 32,461 patients on 41 wartime voyages, covering over 382,000 nautical miles in the process.

Although Oranje re-entered commercial service on the same pre-war route for which she had been designed, the political climate had changed dramatically in the ensuing seven years. Like so many European powers the Dutch found themselves involved in an unwinnable, distant war. Rather than facilitating the maintenance of colonial rule Oranje and her fleet mates more often served as evacuation ships. Westbound voyages were regularly fully booked with passenger lists comprised of apprehensive families moving permanently to a homeland many of them had ironically never seen before.

The passage itself could also prove traumatic. In early April 1947 Oranje encountered 30 ft waves during a severe storm in the Bay of Biscay whilst inbound from Batavia. Together with widespread seasickness, the tempest led to multiple minor injuries and the tragic deaths of four crew members.

In December 1947 Oranje was joined on the East Indies run by the comparable (in terms of speed, size and passenger capacity), wartime delayed Willem Ruys of Royal Rotterdam Lloyd. The two companies operated a tandem service with the respective flagships starting a long association as rivals and partners, careers indelibly entwined. The ships were popular for the standard of their accommodation and facilities, as well as their speed and were patronised by a range of high profile passengers, including the Sultan of Deli and the Prince and Princess Bhanubandh of Siam. Nevertheless the very reason for their existence was in a state of flux, these were colonial liners sailing in a post-colonial world.

By the end of the decade the Dutch position in Indonesia had become untenable and on 27th December 1949 Queen Juliana signed the document formally recognising independence and transferring power to the United States of Indonesia. One repercussion was a certain agitation amongst the Javanese crew, which manifested in strikes and walkouts over a range of issues, including which version of the national headdress should be worn. As the new country drifted away from their former colonial masters, it directly impacted on the Nederland Line’s passenger loads, instigating a decline which resulted in a steady erosion of the company’s profits. Some financial pressures were self-inflicted.

The close bond between Oranje and Willem Ruys became rather too intimate on the tranquil night of 5th January 1953 as they navigated the Red Sea. Earlier in the evening Captain H. Hemmes had announced that the south bound Oranje would encounter her running mate around midnight. At 23:32 the vessels made visual contact. The officers on the bridges of both ships had prepared for the customary passing spectacle, only on this occasion a series of manoeuvres and misunderstandings led to confusion and ultimately a collision.

Fortunately there were no fatalities or serious injuries but the resulting damage cost millions of guilders. One direct casualty of the event was Captain Hemmes who was relieved of his command on arrival at Tandjong Priok. The ensuing investigation and court case lasted five years, ultimately allocating sixty per cent of the responsibility and financial costs on Nederland Line.

In 1956 the Suez crisis and the canal’s closure necessitated a 4,300 mile detour via the Cape of Good Hope to reach Djakarta, thereby emulating her maiden voyage. Despite an increase in fares, passenger carryings, especially westbound remained buoyant. The following year Sukarno’s Indonesian administration nationalised Dutch interests and severed all diplomatic ties with the former mother country, so that by the end of 1957 underlying tensions created a hostile environment for remaining Europeans. On 4th December 1957 she was delayed by three hours as fearful Dutch families booked last minute passage for Amsterdam. Westbound sailings in January and March 1958 were full of businessmen, plantation and estate owners, those final vestiges of colonialism and consignments of women and children to Singapore and Europe. Over the subsequent summer Oranje made her first tentative steps into the Mediterranean and North European cruise market however by then Nederland Line had decided to extend their Indonesian service to the Antipodes.

On 5th November 1958 she departed Amsterdam with 670 passengers on her first such voyage, rekindling memories of those wartime heroics as she arrived in Melbourne on 5th December and Sydney two days later. The following year Oranje received a major refit that included the installation of a central cinema and accompanying veranda, together with the updating and reconfiguration of passenger accommodation. Externally the glazed veranda/cinema section on Promenade Deck was the main physical alteration although aft decks were also extended. Upon completion she had a revised passenger capacity of 323 First Class and 626 Tourist Class.

In September 1960 Oranje joined Willem Ruys and Johan Van Oldenbarnevelt, in a combined ‘Royal Dutch Mails’ around the world service, initially sailing via Suez but subsequently switching to a westerly course, outbound via Panama from February 1961. In May the following year Oranje was selected for a special North Sea cruise in celebration of Queen Julianna and Prince Bernhard’s silver wedding. Joining the sovereign and her consort (who had watched on anxiously during the ship’s protracted launch ceremony twenty three years earlier) were a broad spectrum of European royalty and heads of state. After her moment in the regal limelight the ship then resumed her around the globe voyages.

The new operation gained a loyal following and high praise but soon slipped into the red. It was the same tale globally. The impact of jet air travel on passenger loads coupled with rapidly escalating fuel and manning costs rendered the service increasingly unprofitable. The rumours that had circulated for a while were confirmed early in 1964. On 16th January it was confirmed that Oranje had been sold to the Neopolitan ship owner Flotta Lauro for £1.3 million. Two days earlier the same firm had purchased Willem Ruys. Under the terms of the sale Oranje would complete her advertised programme of voyages, including around the world and a series of cruises to the Atlantic Islands, the Baltic and finally the Mediterranean. Having returned from this last voyage Oranje was de-stored and her works of art removed. On 4th September she was handed over to the new owners and renamed Angelina Lauro, after owner Achille Lauro’s wife. He gave his own name to the other acquisition, the former Willem Ruys.

Angelina Lauro sailed to Genoa almost immediately and entered the Cantieri del Tirreno shipyard for one of the most ambitious conversions yet undertaken. Although this was in many respects the heyday of new Italian passenger ship construction there were a number of yards that specialised in conversions, including the successful transformation of the Cunarder Media into the modern and stylish COGEDAR liner Flavia.

She was nearing completion on 24th August 1965 when a fire swept through the ship. In addition to causing widespread damage there were tragically six fatalities amongst the workmen on board. It wasn’t until the following day that the flames were finally extinguished, by which time large swathes of the renovated interiors had been destroyed. Investigations into the source of the blaze had barely begun when four days later Achille Lauro suffered the same fate, at the Palermo yard undertaking her conversion. Arson was suspected from the beginning but never proven. It remains the most likely explanation for what was otherwise an exceptional coincidence, almost certainly politically motivated against the ship’s new owner (Lauro was Mayor of Naples and had been linked with successive right wing political parties including an historic association with Mussolini and the Fascists).

Due to the fire the ship’s introduction was delayed by six months, however when Angelina Lauro finally emerged from dry dock for acceptance trials in the spring of 1966 she was virtually a new ship, certainly unrecognisable, inside and out, from her previous incarnation as Oranje. The hull retained its trademark tumblehome but now sported a new, more sharply raked bow which extended her length by 4.9 meters (16 feet). In addition to being an aesthetic improvement the rebuilt bow also improved her sea keeping qualities, ably assisted by a newly installed pair of Denny-Brown fin stabilisers built under licence at San Giorgio. The superstructure was comprehensively remodelled, extended fore and aft and fitted with a new streamlined bridge front. Aft of centre were broad, terraced sun decks and two pools (an adult and a children’s) for each class. The First Class adult pool area was screened by a retractable glazed roof, one of the first installed on a passenger ship, which allowed the area to be used in all weathers and double as an intimate night club. The former tiered open promenades on each flank were enclosed within the body of the ship and in some instances incorporated into full width lounges. At the summit a modern, bridge mounted radar mast replaced the previous foc’sle mounted one, but undeniably the most startling and impressive external modification was the new funnel.

Displaying the tell-tale influence of Professor Carlo Mortarino and his team at the Turin Polytechnic, Angelina Lauro now possessed a lofty stack topped by an enormous smoke deflecting soot shield, referred to as ‘the angels wing’. Mirroring in some ways the hull shape the funnel seemed exceptionally broad when viewed directly from ahead or astern but slender beam on. In part this was an optical illusion caused by the plated in front and louvered back (which was neatly mirrored by the mast). Lauro also introduced a smart new hull livery, replicating the same deep ‘Neopolitan’ blue of the funnel and featuring a white sheer band. If externally she now looked the very essence of Italian chic, internally the transformation was arguably even more impressive.

Carlo Pouchain was the designer tasked with taking a twenty five year old, conservatively decorated colonial liner and transforming her into a modern, efficient emigrant carrier, with twice as many passengers. The results were singularly impressive. The public rooms and cabin accommodation were entirely reconfigured to meet the new owner’s demands and considerably increased passenger load. There were two classes, nominally 180 berths in First and 1050 in Tourist, although with a high degree of flexibility as almost 200 were ‘interchangeable’. Given the nature of her service there was further provision for an additional 150 children under the age of 12 in what were somewhat disingenuously referred to as ‘cots’. New cabins were installed in now redundant cargo holds, they might have been cramped but some 90% had private bathroom facilities.

Inevitably there were those who mourned the passing of Oranje’s rich woods and old Dutch charm but Pouchain’s extensive use of modern synthetic materials, imbued the Angelina Lauro with a fresh, functional but nevertheless luxuriant feel. The rooms were enhanced by a fine and eclectic collection of contemporary Italian artwork commissioned from the likes of Giorgio de Chiro, Marcello Mascherini, Tranquillo Marangoni, Federico Morgante and Luciano Minguzzi.

On the engineering side the main engines were thoroughly overhauled and auxiliary power enhanced by the installation of a supplementary pair of Fiat 1,100 kW units. A new air-conditioning system was installed and perhaps most significantly engine room systems and controls automated. This allowed remote monitoring and operation by a significantly reduced engineering crew.

On 6th March 1966 the svelte Angelina Lauro cast off from Bremerhaven on her maiden voyage to Australia, arriving in Sydney 30 days later. For the next six years she sailed in tandem with Achille Lauro, transporting thousands of Europeans to new lives in the Antipodes.

From 1967 and the closure of the Suez Canal in the wake of the Arab-Israeli six day war the ships sailed once more via South Africa, then in the early 1970s returned to Europe via the tip of South America. It was a final, desperate attempt to fill berths. In November 1971 a Quantas Boeing 747 ‘Jumbo’ jet flew from Heathrow to Sydney via Bahrain and Singapore, the writing was on the wall.

Having lost the emigrant contract and in the face of overwhelming airline supremacy Lauro reappraised their position and decided to pull out of the liner business. So it was that Angelina Lauro departed Sydney for the final time on 17th May 1972 and returned to Europe for a comprehensive refit, emerging as a one class cruise ship for 800 passengers.

Angelina Lauro was relocated year round to the Caribbean. Given the company’s lack of representation and experience in that highly competitive market management was sensibly contracted out to fellow Italians, Costa Line. The ship thrived to the extent that in 1977 Costa secured a three year charter, keeping her on the same itineraries out of San Juan and now sporting their familiar yellow funnel with a prominent blue ‘C’.

Her future appeared eminently secure until 30th March 1979 when she lay alongside the outer berth at St. Thomas in the US Virgin Islands on the last day of a seven night cruise. The fire started in a galley and rapidly spread through the adjacent dining rooms.

Despite their best efforts the crew were unable to control the blaze and although tow lines were secured she could not be moved. Thankfully the majority of passengers were ashore and there were no casualties other than the poor, unfortunate Angelina. By the following day the scorched hulk sat pathetically slumped against the quay. Three months after the fire the German firm Eckhardt & Company were awarded the contract to remove the wreck. Utilising heavy lift cranes the remains were righted and prepared for a final trans-Pacific voyage under tow to Taiwanese breakers.

Perhaps inevitably given the extent of the damage her forty year old hull started to take on water mid-ocean. Over the next three days the list steadily increased until just before daybreak on 24th September she finally slipped beneath the waves.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item