As I begin this article, Poland once more finds itself on a geopolitical fault line, perched precariously in lands that have been disputed by, and/or arbitrarily sub-divided between ’Great Powers’ for much of the past two hundred and fifty years.

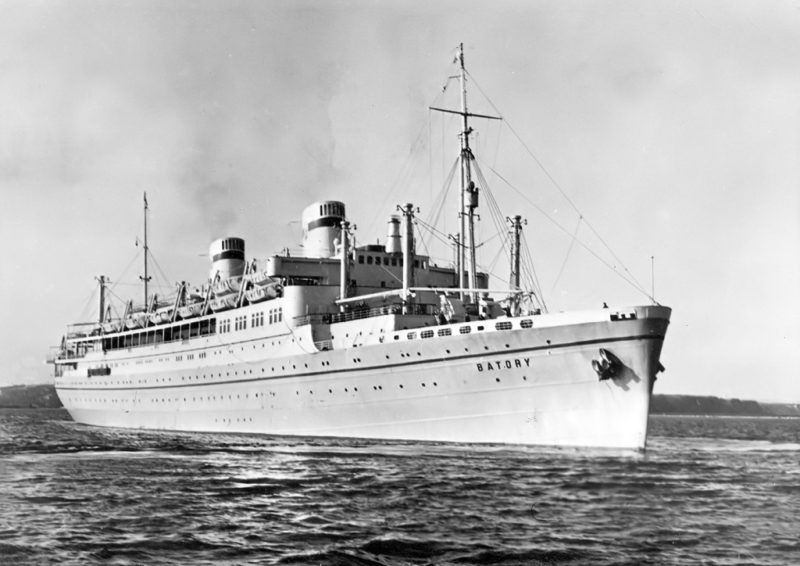

This article is about two ships which in name and deed exemplified the spirit and stoicism of the country they represented. In an era when passenger ships showcased a nation’s artistic, cultural and scientific capability, the Gdynia-America Line’s flagships more than fulfilled that mandate. Piłsudski’s career would be cut tragically short in that dreadful autumn of 1939, but Batory would go on to be the very embodiment of the ‘Ship of State’, reflecting the seismic political and cultural transition experienced by her homeland in both its pre and post war incarnations.

That Poland had a transatlantic steamship company at all was an achievement. The Second Polish Republic was formed under the auspices of The Treaty of Versailles in June 1919, securing land previously held by Germany, Russia and the Austro-Hungarian empire (the First Republic is something of a misnomer, referring to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth which emerged from the longstanding Kingdom of Poland and held sway over one of the most populace and culturally diverse territories in Europe from 1569 to 1795). The new post First World War republic was a fragile assemblage and the national boundaries were only consolidated after a series of conflicts with neighbouring Ukraine, the Weimar Republic, Czechoslovakia, Lithuania and most significantly the Soviet Union.

Access to the sea had been one of the pre-requisites of Poland’s ultimate support for the allied cause and one of Woodrow Wilson’s 14 points (which constituted the United States’ wartime objectives). The negotiated solution was a thin strip of land, referred to as the Polish corridor, separating the main body of Germany’s new Weimar Republic from its satellite East Prussian province. The only significant deep water harbour facility in the corridor was the nominally ‘Free City’ of Danzig, but its population was 98% German speaking and its political alignment decidedly Teutonic. Simmering discontent reached a peak during the Polish-Soviet War of 1919 to 1920, when dockworkers went on strike and refused to unload armaments bound for the Polish Army. Riled and concerned by this deteriorating situation the Polish authorities’ radical solution was to build its own port facility. The location chosen was the then small fishing community of Gdynia, just 10 miles to the north of Danzig. Despite setbacks and funding problems, the project, inaugurated in the winter of 1920 and masterminded by Poland’s Finance Minister Eugeiusz Kwaitkowski, was an ambitious success. In August 1923 the first major ocean-going vessel called at the port, which was trans-shipping in the region of 10,000 tons of cargo annually. By 1929 the port was handling a remarkable 2.9 million tons of cargo. Within a year of that Poland had established a transoceanic passenger shipping company.

The new national carrier emerged through a combination of political willpower and commercial expediency. The United States introduced the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 (which was consolidated by the Immigration Act of 1924), drastically reducing the number of America bound migrants from Europe. Amongst the shipping company’s most significantly affected was the Baltic America Line, formerly the Russian American Line, which embarked a sizeable number of Polish passengers at Danzig. Baltic America was actually a subsidiary of Det Østasiatiske Kompagni, the famous Danish based East Asiatic Company and already suffering from the convulsions of the Russian revolution and the ensuing civil war.

By 1930 East Asiatic were looking to divest themselves of the loss making Baltic America Line, just as the government in Warsaw was considering entering the transatlantic fray. A company Polskie Transatlantyckie Towarzystwo Okrętowe or PTTO was formed, jointly owned by East Asiatic and the Polish government, which would operate under the trading name of Gdynia-America Line. The new venture inherited three small ships, the Polonia, Estonia (renamed Pulaski) and Lithuania (renamed Kościuszko) which had originally been built for the Russian American Line as Kursk, Czar and Czaritza between 1910 and 1915.

Ordering new liners became a priority, both practically to provide an improved service but also as a projection of national pride. In the absence of domestic shipbuilding facilities the company was forced to seek tenders abroad, but in the midst of the Depression and with the Polish economy consequently weak the government was unable to allocate sufficient funds. A solution was brokered by their Italian counterparts. What it lacked in hard currency Poland made up for in natural resources, especially coal, and so payment of the 62 million lire price tag (approximately £3 million) was to be made by way of a barter agreement, with an equivalent value of coal to be supplied to the Italian state railways over the following five years.

A formal contract was signed with Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico (CRDA) on 29 November 1933. Under the guiding hand of its talented technical director Nicolo Costanzi, the builder had recently completed a 14,000 ton liner for Lloyd Triestino’s intra-Mediterranean service which broadly mirrored the Poles’ requirements and had attracted widespread adulation. Victoria would therefore provide the blueprint for the new Polish ships.

In March 1934 the first ship’s keel was laid on the slipway at Monfalcone. Just nine months later, on 19th December 1934, she was launched into the chilly Adriatic. The 525ft 8in long, 70ft 9in wide ice strengthened hull, with ten watertight compartments, was clearly a development of Victoria and the contemporary Italian Line vessels Neptunia and Oceania. The name bestowed on the ship was unapologetically patriotic, honouring the still dominant national figurehead, a Marshal of Poland whose heroic exploits in The Great War and the ensuing Polish-Soviet War had proven the springboard to a largely successful political career. Józef Piłsudski was generally beloved by his countrymen and probably the most high profile Polish man of his era, although he had detractors who considered him a dictator, especially after his role in the May Coup of 1926.

Seven months after Piłsudski (the ship) took to the water and as she neared completion at the fitting out berth the second vessel was launched on 3rd July 1935. Again the name honoured a Polish national hero, although this time from a much earlier era. The ship was called Batory after a 16th century King of Poland whose commonwealth army repulsed and ultimately defeated the Russian forces of Ivan ‘The Terrible’, in the Livonian campaign. The names proudly reflected the country’s heritage and determination to assert its relatively new found independence.

The ships almost never made it to their homeland. There were rumours that Piłsudski might be requisitioned by the Italian government for trooping duties in anticipation of the planned Abyssinia campaign. To the relief of her owners such talk was dismissed by both shipyard and ministry and Piłsudski was completed as intended in August, running successful trials in the Adriatic. She then paid a brief customary courtesy call at Trieste’s stazione maritime, before sailing for Gdynia where she arrived on 12th September to receive final provisions before the maiden voyage. Externally there was a clear familial resemblance to the beautiful Victoria, with a broadly similar superstructure arrangement (all enclosed forward with open promenades stretching aft on the flanks) surmounted by two, evenly spaced, teardrop funnels. Unlike the Lloyd Triestino vessel which had a modern bridge mounted foremast Piłsudski’s was ‘traditionally’ placed forward of the bridge, on an extension of A deck. The mainmast was aft on Boat deck. Both masts were bracketed by a pair of kingposts, with associated booms to service the four cargo holds, two forward, two aft.

That pleasing, balanced profile was further enhanced by the company livery. This consisted of a black hull with a broad white sheer stripe and green boot topping, below a white superstructure surmounted by two buff coloured funnels. Two thirds up the funnels featured a broad red stripe incorporating a shield with the company initials ‘GAL’ and a nautical trident. The masts were also buff. Adding a unique touch to the already smart look was a bold bow decoration, a huge replica badge from Piłsudski’s famous First Brigade, which he commanded in the Great War, rendered in silver-grey by sculptor Wojciech Jastrzębowski. The badge incorporated his initials and a central eagle emblem and was flanked by oversized renditions of the distinctive zigzag collar blades of a Polish general.

Perhaps the only blemish on the palpably festive preparations for the maiden voyage was that the new ship’s namesake wasn’t there to witness it. He had died the previous May. Referring to the great soldier and statesman, Bishop Okoniewski of Pomorze blessed the ship’s ensign on 14th September and commented, “The liner Piłsudski is a symbol of Poland’s might and the proudest monument for Poland’s greatest son”.

Dressed overall, the new national flagship departed from Gdynia’s Nabrzezu Francuskim (the French Pier) the following day, heralded by the cheers of onlookers and the whistle salutes of tugs and other vessels in port. She sailed under the command of Captain Mamert Stankiewicz, whilst amongst the passenger complement were the President of Warsaw, Stefan Starzyński and General Gustaw Orlicz-Dreszer.

Those first passengers settled into a ship of quite startling modernity, with a unique class delineation. Eschewing First or even Cabin class, the highest standard cabins and public rooms were controversially and counter intuitively designated Tourist class. It was a deliberate and quite ingenious ploy by the Gdynia-America Line to undercut the competition allowing them to charge lower fares for superior accommodation under North Atlantic Passenger Conference rules and attract more egalitarian-minded American clientele. Marketing for the ships unashamedly focussed on this. One brochure espoused, “The social atmosphere that pervades the Tourist class quarters of the Polish Line ships appeals to American passengers because it is one of true democracy…….”. Getting carried away the brochure continued, “…..a wholesome air of equality, a refreshing feeling of emancipation gives Americans the sense of carrying the ideals of their own land across the ocean with them”. It was true that, “He (an American) will find no doors marked ‘No Admittance’ to bar his strolls and explorations”, nevertheless there was an assortment of special Tourist class accommodation on Promenade and Boat Deck, most with private bathroom facilities, including full bath tub, and one Suite de Luxe with its own separate sitting room. To paraphrase George Orwell, all passengers were equal but some were more equal than others.

The residual 370 Tourist class and 400 Third class passengers were accommodated in a range of cabins on A, B and C decks, most without private facilities.

As soon as the orders had been placed the Polish Trade Ministry set up an Art Committee to oversee the decoration. It incorporated representatives from the Warsaw Academy of Fine Art and Warsaw University of Technology, led by Professors Tadeusz Pruszkowski, Lech Józef Niemojewski, Wojciech Jastrzębowski and the architect Stanisław Brukalski. The Committee was tasked with identifying and selecting works for inclusion on the ship, to complement the overall functional aesthetic. For the artists selected, many already feted in their homeland and beyond, it often represented the most prestigious commission to date.

Niemojewski and Brukalski were instrumental in developing the ship’s interior design, working closely with the head of the shipyard’s fitting out department, the renowned Nino Zoncada.

The tone onboard was in many respects set by Brukalski’s Tourist class entrance lobby on A deck. Entering from the gangplank, passengers were met by a light and airy space of pale partitioning illuminated by eight circular lights in two rows of four. The two-tone linoleum floor was overlaid by three, broad white stripes which beckoned passengers from the shell doors on either flank to the central stairwell and lifts. Surrounding the lobby were an assortment of Purser’s offices, a shop, barber and beauty parlour. Opposite the lift and stairs was a large portrait of the Marshal himself by Zygmunt Grabowski, resplendent in full dress uniform and framed in black panelling and the hand rails were also black. Heading aft via doors on either side of the lift/stairwell passengers entered the rectangular Tourist class dining room which spanned the ship. Light came from nine portholes running along each flank grouped in threes and circular lamps, with tables for four in the centre of the room and a small selection of tables for two lining the room. Galleys for both this restaurant and its Third class equivalent aft were located centrally. Indeed, heading aft on A Deck was almost a Third class replica of the Tourist class space forward, as if a mirror had been placed mid-galley. Aft of the Third class dining room was that class’s embarkation lobby incorporating a shop, barber, beauty parlour and office, then a selection of cabins. A small Third class lounge was located farthest aft, opening onto the fantail at the stern.

Most public rooms were situated up a single flight on Promenade deck and followed the broad orientation of Tourist class forward and centre and Third class further aft. Tourist passengers exiting the stairs or elevator doors, and therefore facing forward, entered an entrance hall, equivalent to the lobby space below, with the ladies room situated forward to the right and writing room forward to the left. Farthest forward and surrounding these rooms was the horseshoe shaped veranda lounge, entered on either flank of the hall or through a small passageway forward.

The focus of life onboard and undoubtedly the most impressive room aboard was the Tourist class social hall by Lech Niemojewski, with input from Wacław Borowski and Wojciech Jastrzębowski. Light and bright in colour and tone it featured a blue linoleum floor with an inlaid black dance floor, criss-crossed by single and double white gridlines and sandy coloured upholstered furniture. White pillars decorated with images of animals, musical instruments, fruit and pottery supported ceiling panels inlaid with spherical lights and a large recessed circle of indirect illumination above the central dance floor. On each side of the room were female nude sculptures by Tadeusz Breyer holding large up-lighters and symbolically depicting Europe holding a model of Columbus’ Santa Maria and America holding a model of the Statue of Liberty.

The room’s aft bulkhead which abutted the aft funnel casing had a bandstand, complete with a white grand piano to entertain and accompany dancers. The black wall doubled as a sliding screen which on Sundays and religious festivals could be withdrawn to reveal a Catholic altar and exquisite statue of Madonna with Child entitled ‘Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn’ by Antoni Kenar. Also abutting the bulkhead was a small cinema.

Heading aft on Promenade deck was the Tourist class children’s room and some of those special Tourist class cabins previously mentioned. Oddly the most exclusive of these backed onto the Third class smoking room, with that class’ games deck overlooking the stern.

One deck higher, Boat deck, was exclusively Tourist class territory other than the officers quarters and wireless room farthest forward. Most space was given over to cabin accommodation, the outside ones looking out onto slim open promenades and deck mounted lifeboats. Aft of the central stairwell was a detached block incorporating Brukalski’s Tourist class smoking room with a long bar counter and accompanying stools. The intimate ’comfy’ seating was mainly focussed around a statue ’Girl with Jumping Rope’ by Adolf Karny on the forward facing bulkhead.

Aft and in contrast to the heavy smoking room atmosphere, was the light and airy Tourist class veranda café. With its wicker furniture and quirky tables this was a perfect place to while away afternoons at sea, looking out over the games deck and the wake beyond.

Highest of the accessible decks was the appropriately named Sun deck, featuring two deck tennis courts and multiple benches for when the weather was fine. Also located here, aft of the second funnel was an oversized lifebelt offering a perfect photo opportunity. Meanwhile at the forward end of Sun deck were Captain Stankiewicz and his senior staff’s cabins and their principle workplace, the bridge.

As previously alluded to, B and C deck primarily comprised Tourist class and crew cabins whilst the lowest passenger space, the indoor swimming pool and gymnasium, were down at the foot of the forward stairwell in the bowels on D deck.

The maiden voyage was blessed with fair weather and Piłsudski’s Sulzer two-stroke engines generating 6,250bhp at 130rpm, easily maintained her 18 knot service speed. The ships’ engine rooms also incorporated two Cochrane composite boilers for steam requirements and four electrical generators also powered by Sulzer diesels for auxiliary power and electrical demands. They were amongst the most economical power plants afloat, consuming on average 42.8 tons of fuel per day (39 tons for the main propulsion) during their first year of operation.

At noon on 24th September 1935 Piłsudski anchored off the New York Quarantine station. Officials and dignitaries boarded for a reception and lunch before the flag bedecked liner proceeded through Lower Bay, past the Statue of Liberty and approached Manhattan. Pleasure boats filled with cheering crowds and tugs swarmed around her as she passed Battery Park, before pirouetting into the company’s Sixth Street Hoboken berth on the New Jersey shoreline, bathed in late summer sunshine. Even in an era punctuated by gala arrivals (Normandie’s Blue Riband maiden reception had happened just three months earlier), the Piłsudski’s would live long in the collective memory.

Alas the afterglow of that maiden voyage arrival was tainted on just her second Westbound crossing. Despite the impeccable credentials of her designer and builder, the North Atlantic is an unforgiving environment, an ultimate testing ground ready to expose any weakness. Piłsudski ran into successive storms on that November 1935 crossing, resulting in significant structural damage and stability concerns which could not be glossed over. Temporary repairs were effected at her Sixth Street berth but more significant modifications were required to make her properly seaworthy.

The lessons learnt from that terrifying crossing were applied to the still incomplete Batory, so that there were no concerns by the time she was ready for trials in April 1936. Later that same month Batory departed Trieste on a cruise like delivery voyage, visiting Dubrovnik, Barcelona, Casablanca, Madeira, Lisbon and London before a festive arrival in Gdynia to be provisioned for her 18th May maiden voyage.

The ships were structurally identical and decoratively similar. Like her older sister, Batory was the work of selected Polish artists and architects working closely with their Italian colleagues. Nevertheless these were also known as the ’International ships’ on account of the broad range of nationalities contributing everything from hull steel (Czechoslovakia), kitchen utensils (USA), switchboards (Germany), boilers and distillation equipment (UK) and laundry equipment (Denmark). A large portrait of her namesake hung in Tourist Class lobby.

Although nominally an express service from Gdynia to New York via Copenhagen, in practise the ships haphazardly picked up both passengers and cargo at several ports fringing the Baltic Sea, including Gothenburg, Helsinki, Riga and Tallinn with occasional calls at Halifax on the Atlantic’s Western seaboard. In September 1936 Piłsudski made a well publicised detour to the St Lawrence, calling at Quebec and Montreal. Each round trip was scheduled to take about three and a half weeks, facilitating ten per annum. From the beginning they were also designed for cruising, with a range of itineraries including the fjords in mid-summer and the Caribbean at Christmas and New Year.

In what must have provided an unnerving sense of déjà vu, Piłsudski was delayed 48 hours by stormy seas in late November 1936. Captain Zdenko Knoetgen, relief captain in command of the ship during the absence of Captain Mamert Stankiewicz, reported that the storm was incessant for six days. Fortunately the previous year’s structural work held. In fact both ships suffered early travails, with Batory’s being that most feared of all maritime risks, fire.

A year after entering service, on 3rd June 1937, Batory was 800 miles off New York on a westbound voyage when fire was reported in the engine room. As the crew fought the blaze the east bound Piłsudski stood by to render assistance. Ultimately it was brought under control and the ship was able to proceed to New York, remaining at her Hoboken berth for a full month whilst repairs were effected. The cause on this occasion was tracked to mistakes made whilst bunkering in Copenhagen, however in those pre-war years she remained particularly susceptible to random conflagrations, some of which may have been started deliberately.

The sisters proved enduringly successful. Indeed Gdynia-America Line were occasionally forced to draft one of the South America vessels, their predecessors, to supplement the peak schedules. There were even suggestions of a possible third ship. Such optimism slowly dissipated as the decade progressed, with concerns about the increasingly tense European situation thwarting and delaying travel plans. Polish security relied on the ideological stand-off between Nazi Germany and the Soviet governments negating each other’s influence. That tenuous balance was shattered by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 23rd August 1939. Piłsudski was scheduled to depart Hoboken for Gdynia via Copenhagen that same day, although her actual manoeuvres in those last few days of peace remain something of a mystery. Five days later with the German invasion imminent, all Polish flag vessels were ordered to remain outside the Baltic and stay within international waters. Ultimately she made it to the relatively safe haven of the UK.

Batory sailed from Gdynia on 24th August 1939, arriving at Hoboken on 5th September to disembark her 642 passengers. With their homeland now at war and rumours that she would be commandeered for carrying munitions, almost two thirds of the crew mutinied, refusing to obey orders as the ship anchored in the Hudson.

Ultimately local police were called in to remove the mutineers and on 22nd September she sailed for Halifax. Despite her subsequent exploits reading like a ‘boy’s own’ fable of heroism and derring-do, the faltering start to Batory’s wartime career continued even after she was transformed in the Canadian port for troop transport duties. Indeed it would be almost three months before she finally departed. Coal was the cause.

To the surprise of many, although the country was in no position to fight having expended so much military capability in Abyssinia and Spain, Italy declared itself neutral in the unfolding European conflict. Nevertheless Mussolini’s government indirectly hampered the Allied war effort by choosing this moment to sue Batory’s owners for defaulting on $400,000 worth of coal shipments. For almost three months as the legalities and politics played out, Batory remained tethered impotently at her Halifax berth. By the time she belatedly sailed for Europe her sister had already perished.

Piłsudski was transformed for war service on the Tyne, leaving Newcastle on the dark, cold winters evening of Saturday 25th November 1939, alone and without naval escort. She retained her black hull but the rest of that vibrant pre-war livery had been repainted uniform grey. For protection she had a 4 inch gun installed on the aft deck. Despite posters and campaigning to the contrary, the ship’s destination was widely known, she was bound for Australia to pick up a first consignment of troops. Reports vary but her Polish crew of about 180 were supplemented by 14 British seamen. There may have been other personnel onboard who joined at the last minute.

Shortly after 0400 the following morning Piłsudski passed Flamborough Head on the North Yorkshire coast, heading for the outer Dowsing area of the North Sea. The sea was rough and she was proceeding at about 19 knots when at 0536 the ship was rocked by a huge explosion, forward on the port side. She immediately took on an alarming 10 degree list to port and Captain Stankiewicz ordered the crew to go to their lifeboat stations. Shortly thereafter the damaged ship shuddered from a second explosion, she was then off the mouth of the Humber, some 18 miles east of Withernsea.

Although some authors still inaccurately suggest that she was sunk by torpedoes, it was two magnetic mines that detonated on Piłsudski’s hull that bleak Sunday morning. They had been laid by units of the Kriegsmarine’s 4th Destroyer Flotilla consisting of the destroyers Z11 Berd von Arnim, Z12 Erich Giese and Z13 Erich Koellner, under the command of Commander Erich Bey.

Despite the rough, freezing seas and the ship’s list, the crew managed to get away in six lifeboats or scramble on to rafts. True to form Captain Stankiewicz was the last to leave his ship. Defying expectations Piłsudski remained afloat for four hours after the initial explosion but eventually she slipped below the surface, coming to rest in about thirty metres of water.

One hundred and three survivors were picked up by a British destroyer with a further eighty six making it to shore onboard a trawler. Only ten deaths were reported, including a sixteen year old engineer and the ship’s commander. Although taken onboard the destroyer from a life raft Captain Stankiewicz died soon afterwards from a combination of shock and hypothermia. He became an instant national hero, immortalised in his First Officer Karol Olgierd Borchardt’s book and buried with full honours in the West View Cemetery, Hartlepool. Interestingly and in stark contrast to Stankiewicz, Batory’s pre-war Captain was a larger than life character, Eustazy Borkowski. Rarely without a Cognac in his hand, multi-lingual and a consummate host, Borkowski was a favourite of both press and public but he fell out of favour during the war and lived out the rest of his days in New York exile.

Batory finally departed Halifax in late December. She was chartered by the British Admiralty, retaining her residual Polish crew but supplemented by British seamen and placed under the management of Lamport & Holt. On that first voyage she took about 2,000 Canadian troops to the Clyde, departing Scotland on 10th January 1940 bound for Suez to bolster the Allied forces in North Africa. For six weeks she shuttled back and forth across the Mediterranean between Suez and Marseille before heading north to Liverpool where she arrived on 22nd February. Having taken on more troops on the Clyde, Batory joined fleet mate Chobry and three other liners, Empress of Australia, Monarch of Bermuda and Reina del Pacifico, to form convoy NP1 on 11th April. Accompanied by a heavy escort including the battleship Valiant, battle cruiser Repulse and no fewer than seventeen destroyers, the ships sailed for Narvik, supplying troops and equipment to resist the German invasion of Norway. Batory returned to Norway in early May, part of convoy NP3, in company with Sobieski and three escorting destroyers, surviving several bomb attacks and earning herself the self-fulfilling nickname ‘The Lucky Ship’. In contrast the nearly new Chobry was sunk after an attack by German JU 87 Stuka dive bombers in Vestfjorden on 14th May 1940.

Fresh from her Norwegian exploits but with the Allied armies now in full retreat, Batory spent two weeks from 13th to 27th June evacuating French and residual British Expeditionary Force troops from the Biscay ports of St. Nazaire, Bayonne and St. Jean de Luz. France had fallen by the end of the month and the Allies were in disarray. The situation was so critical that the new Churchill government instigated Operation Fish, a covert plan to send much of Britain’s gold reserves to Canada. On 4th July 1940 Batory sailed from Greenock as part of a convoy of five ships. She carried a reputed 2,950 crates of bullion and bank notes, together with 34 crates of historic Polish artefacts which had been smuggled out from Wawel Castle, Cracow, via neutral Romania. The treasures were arguably priceless, including ‘Szczerbiec’, the jewelled Coronation sword of Polish Kings dating back to 1320, huge Flemish tapestries and the Annals of the Holy Cross, written by Archbishop Jacob of Znin in the early 13th century and thought to be the oldest preserved original Polish document. Somewhat more contemporary elements included thirty six original Chopin compositions and accompanying correspondence.

The journey across the Atlantic was fraught with danger, which was exacerbated when Batory developed engine problems and fell out of the convoy. Escorted by the cruiser HMS Bonaventure she dodged icebergs, fog and the U-Boat menace to finally land her precious cargo at Halifax on 12th July.

Having embarked another consignment of Canadian troops Batory sailed from Halifax on 23rd July 1940, in company with seven other transports, including Sobieski, as part of convoy TC6, arriving in the Clyde estuary on the first day of August. Just under a week later Batory left as a constituent part of one of the large troop convoys of seventeen ships known as the ‘Winston specials’.

This was WS2. In many respects her cargo was even more precious than the bullion voyage to Canada, for alongside the troops destined for Bombay, Colombo and Singapore were 480 London children, escaping The Blitz to start a new life in Australia. Once out in the Atlantic the convoy split, with Batory joining the ‘fast’ detachment of seven ships escorted by the cruiser HMS Cumberland. Although water had to be rationed, food was plentiful and Captain Deycranowski, referred to as ‘Hawkeye’ by the children, and his crew made every effort to keep the kids entertained on the long and perilous eleven week voyage. Their efforts were rewarded with another affectionate nickname, ‘The singing ship’, a happy sobriquet in dark times.

Having disembarked the last of her emigrants at Sydney on 16th October 1940, Batory remained in the region until the end of the month, including a much needed period of maintenance and dry-docking in Singapore. At the start of November she picked up a consignment of New Zealand troops in Wellington and then departed Sydney on 14th November in company with Orion and HMAS Perth. They met up with other vessels in The Great Australian Bight before making for Fremantle, Colombo and ultimately Suez a month later.

There was no respite. From Suez, Batory sailed south, around the Cape of Good Hope and back to a frigid Scotland, where she eventually arrived on 8th February 1941. The next twelve months was primarily spent shuttling troops between Greenock and Liverpool but she also made return voyages to Halifax, Gibraltar, Iceland and Lagos. One other interesting interlude was convoy WS 8C, which convened on the Clyde and waited at Scapa Flow in early August 1941, in preparation for the ultimately aborted invasion of The Azores. By the end of the month the plan was cancelled and she had offloaded those troops and materials before making at least one more return crossing to Canada.

From April to October 1942 Batory primarily shuttled back and forth in convoy across the Atlantic, including a first wartime call to New York. Onboard for one of these Westbound voyages was the children’s author Roald Dahl. Having joined the RAF and been injured in a near fatal crash in Libya, Dahl was in transit to Washington to woo the ‘cocktail mob’ and galvanise US support for the British war effort. Interspersed with the Atlantic crossings Batory detoured to places as remote as Iceland, Freetown and Lagos. The hard driven liner was arguably due a break, but inevitably it wasn’t forthcoming.

The momentum of the Allied build-up continued unabated, and the focus at that stage of the war was the Mediterranean. Batory joined convoy KMF1, the first and arguably most important element of ‘Operation Torch’, destined to drive Axis forces out of North Africa. One of more than forty merchant vessels with a considerable naval escort Batory now sported a row of landing craft suspended on each flank and enhanced anti-aircraft weaponry. This veritable armada sailed from the Clyde on 26th October 1942, GIs trained on her open decks and relaxed as best they could on the journey south. On the 8th November Batory and the huge invasion force massed to the west of Oran, where they anchored and troops clambered aboard the Landing craft, directly or via scramble nets, for the terrifying journey to X beach.

Batory made three subsequent, successive return trips between the Clyde and Algiers before preparations were made for the next stepping stone of the Allied push into Southern Europe, the invasion of Sicily. She departed from Scotland on 28th June 1943 as part of convoy KMF18 in company with nineteen other merchant vessels. Despite unseasonably strong winds and inclement conditions the troops once more landed via landing craft on 10th July, forming part of a combined mass of about 160,000 American, British Canadian, Indian and Free French airborne and seaborne operations. Batory survived repeated attacks from dive bombers in the course of ‘Operation Husky’, before somewhat ironically being damaged three days later due to a collision with the Dutch troopship Christiaan Huygens.

After repairs had been effected at Alexandria, Batory passed through the Suez Canal and made for Bombay where she arrived on 13th August. She remained in the Middle East for the rest of the year, making a round voyage in November to Iraq (Basra), Iran (Bandar Abbas) and Karachi. On 28th December 1943 she left Bombay and headed back to the Mediterranean via Suez, where she directly supported the invasions of Italy and southern France with troops and supplies through until October 1944. She was a particularly significant element of the latter campaign (Operation Dragoon), acting as flagship and headquarters for General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, Commander in Chief of the Free French Army. Indeed, probably the only significant European theatre amphibious offensive or defensive operations Batory did not take part in the Normandy landings. Some heroics had to be left to others.

On 10th October, in the company of sixteen other ships comprising convoy MKF35, Batory left Port Said, called at Algiers and then for the first time in more than a year passed westbound through the Pillars of Hercules and out into the Atlantic. With the western English Channel now safely in Allied hands she called at Plymouth before progressing to Liverpool. At the end of the year with 1,265 troops onboard she sailed from the Clyde on 16th December 1944, in convoy KMF37, bound for Gibraltar, Suez, Bombay and Kilindini (Mombasa). Her return trip was via Aden and Gibraltar, arriving in Liverpool on 20th February 1945.

Although the war in Europe was nearing its conclusion Batory’s troop transport days were far from over. She remained in the Mediterranean for most of the year, shuttling back and forth from North African ports to Toulon, mainly with ‘demob happy’ Tommies on board. Nevertheless she is reported as having made at least one particularly convoluted post-VE day voyage that included calls in Iceland (9th June), Madeira (24th June and ultimately Naples on 1st July 1945. She returned directly to the Clyde on 28th December before embarking on what must have appeared at the time to be a final voyage to the Indian sub-continent, returning to Glasgow from Bombay on 17th March 1946.

Finally released from her war service Batory was handed back to her owners. The reformed nation she once more served as flagship had however changed beyond all recognition. The liberation of Polish territory by Soviet forces was almost complete by the time of the Yalta conference in February 1945 and in June 1945 the deceptively named ‘Provisional Government of National Unity’ had been established, a Soviet puppet regime that excluded most members the government-in-exile languishing impotently in London. Batory crewmembers watched developments at home with enthusiasm or incredulity dependent on their political perspective. Several dissenters opted to ‘jump ship’ and seek asylum whilst she lay at anchor in Gareloch in July 1945.

Back to the spring of 1946 and Gdynia America Line sent their flagship to Antwerp for conversion back to commercial service. The refurbishment was delayed by a significant fire which damaged the bridge and much of the accommodation in the forward superstructure. Together with the ingress of extinguishing water four decks were affected in all. Subsequent advertisements promoted her post-war maiden voyage as departing Gdynia on 31st March 1947 calling at Copenhagen the following day and Southampton on 3rd April. In the end she only departed the Belgian shipyard on that last day of March, so rather than heading north for the Baltic she made directly for Southampton.

On 5th April, Batory sailed from the Hampshire port for New York, inaugurating a monthly service which subsequently operated from Gdynia. Her western terminus was now the French Line‘s Pier 88 on Manhattan‘s famous Luxury Liner Row. Incidentally CRDA continued to pursue their legal action against the ship’s owners.

External changes from her pre-war heyday amounted to a new set of kingposts forward of the bridge, which appear to have been installed at some point during her military service, and the decision not to reinstall the ornate bow decoration. Details of the internal changes have proven rather elusive. A later deck plan shows the original Smoking room and Verandah Café on Boat deck were replaced by four large suites backing onto an enlarged Lido Bar. The original special Tourist Class cabins on Promenade Deck had been gutted and now served as the main Tourist Class Lounge, of similar dimensions but necessarily more crammed with furniture than its adjacent First Class equivalent. Conversely the original Third Class lounge on A deck was replaced by cabins.

It was not however these physical changes that struck pre-war regulars who stepped back aboard the ship, it was a more intangible transformation, a decidedly frigid, hesitant atmosphere onboard. Beneath that thin veneer of laughter and immaculate service was an overarching air of suspicion. As Patrick Wright wrote in his book Iron Curtain, “From Stage to Cold War. MS Batory had gone into post-war service as a hard-currency earner and spy carrier”.

The new Polish government and in particular its much feared Ministry of Public Security were now prominent not only in the management of Gdynia-America Line but also the day to day operation of the ship. The Ministry’s primary tool was the Urząd Bezpieczeństwa (UB), a particularly insidious and gruesome secret police force that infiltrated all aspects of public and private life. Captain Jan Cwiklinski was nominally master of the renovated ship but this was little more than an illusion. The most powerful man onboard was undoubtedly second in command Peter Szemiel, a prominent Ubek, the less than affectionate nickname for UB operatives, whose role included the somewhat ironic title of Cultural Officer. Supporting Szemiel was third in command Kaminski, a captain in the UB who organised a spy network onboard and liaised directly with superiors in Warsaw. New recruits were selected as much for their communist loyalties as their seamanship.

Nevertheless even the zealots and the indoctrinated found it hard to escape the lure of the capitalist trappings and relative freedom of Western society. Despite the earnest efforts of the UB, it is said that at least one member of the ship’s complement jumped ship on every New York arrival. Sometimes it was more. In February 1949 nineteen deserted on a single Pier 88 turnaround according to the US immigration service.

Suspicion, bordering on paranoia, reigned on both sides of the Atlantic. The in-depth scrutiny of the American authorities was widely reported, less publicised but even more draconian were the checks at Gdynia. She was unable to dock until Szemiel and Kaminski, in company with embarking UB and Frontier Guard officers, had searched the ship. The crew were detained in the dining room. Anyone found harbouring subversive materials received a warning and a black mark on their record. A second offence resulted in immediate dismissal and in all likelihood a lifetime under surveillance.

As the Cold War intensified, the already brittle relationship with the US authorities grew ever more strained. That bubble burst in May 1949 when Gerhart Eisler, referred to by Time magazine as the Number 1 US Communist, jumped bail and escaped from New York onboard Batory. Eisler was arrested when the ship arrived at Southampton but subsequently released when an extradition request from the US authorities was refused and ultimately settled in East Germany.

There was frustration and anger in America, then in the grip of McCarthyism, and a quite reasonable suspicion that crew members may have been complicit in Eisler’s escape. Batory was now inadvertently the focus of anti-Communist sentiment and on her next New York arrival FBI officers swarmed onboard, whilst US Border guards patrolled the pier and guarded the gangway. Passengers were taken to Ellis Island for screening, whilst the Captain and senior officers were questioned over their involvement in the affair. The words screening and questioned were euphemism’s for interrogation. In fact almost 90% of Batory’s passengers were non-Polish and most of the cargo came from Britain and Denmark, including hams.

Even as she continued to ply the Atlantic sea lanes, encountering tempests and tranquil days just like her fellow liners, Batory continued to attract controversy. Although it was sanctioned by the US authorities, Valentin Gubitchev, a recently convicted Soviet spy was deported on Batory’s 20th March 1950 departure. Five months later there was a quite bizarre event seventy five miles out from New York when one William Newton touched down alongside the ship in a seaplane.

Newton was later accused of ’transporting a stolen aircraft in foreign commerce’ whilst the plane was claimed as salvage by Gdynia-America Line and offloaded at Southampton.

Since the Eisler affair formal measures imposed on all Soviet and satellite states merchant vessels included the surrounding of vessels with guards, the refusal to grant shore leave to members of ship crews, the refusal to allow ship officers ashore except under escort, the stringent interrogation of passengers, and the interrogation of officers and crews on political subjects. Over the subsequent year the Polish Embassy lodged a number of complaints with the US authorities before on 13th September 1950 Jozef Winiewicz, Poland’s Ambassador to the United States, called on Acting Secretary of State Webb to protest at, and ask for relief from, the unfair discriminatory restrictions to which the Batory had been subject over a long period.

What specifically prompted the Ambassador’s protest this time was a refusal by the Longshoremen’s Association to unload Batory’s cargo on her 7th September 1950 New York arrival. They also refused to load her subsequent departure, which included a consignment of medical supplies, specifically streptomycin, from the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund.

The following month the tension was ramped up further when Gdynia-America Line’s vice-president, Czeslan Grzelak was deported for being a member of a communist organisation, a decade after arriving in the US. The New Year promised little change and on 1st February 1951 American shipwrights refused to carry out maintenance and repairs on Batory. Ultimately the Port Authority of New York brought matters to a head, stating that she was ‘an undesirable occupant of her berth’. From 1st April 1951 Batory would no longer be welcome at US ports.

The East Asiatic company made an offer to buy her realising that there was still significant demand for berths and cargo from Copenhagen to New York, but failed to agree a price. Instead she was sent to the Tyne, presumably passing her sister’s wreck off the Yorkshire coast, to be prepared for a new route that would take her East, back to some of her old wartime haunts of Port Said, Suez, Aden and Bombay. She emerged from the refit sporting a new, cooler hull livery of pale grey with a red sheer band. The eagle eyed noticed that the letters on her funnel now read POL rather than GAL, all the disparate national shipping lines had been consolidated into a single entity, the unambiguously named Polish Ocean Lines.

Prior to inaugurating the new passenger service from Gdynia to Bombay Batory was gainfully employed shuttling the young and idealistic from Le Havre, Dunkirk and Calais to her home port. Taking the ship circumvented the barriers placed by Western authorities on those attending the 3rd World Youth Festival in East Berlin during August. With her Festival duties complete Batory finally departed Gdynia on her first trip to Bombay on 17th September 1951, calling at Southampton, Gibraltar, Port Said, Suez and Aden en route. Karachi and Malta were later incorporated in the schedules. The following and each subsequent northern hemisphere summer the service was suspended being Monsoon season in the Indian Ocean, and instead she embarked on a programme of cruises from Gdynia and Copenhagen to the Fjords of Norway, Iceland and the Faroe Islands, to the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Isles. She also made occasional around Britain cruises.

One interesting anecdote from this time neatly illustrates those entrenched East-West tensions. When the SS United States steamed triumphantly into Le Havre at the end of her record breaking maiden crossing in July 1952 she was greeted by whistle salutes from every vessel in port, bar one. Only the secretive Batory remained silent.

The cycle of her liner voyages and cruises was broken only when Batory had her annual refit. In May 1953 the ship sailed to the Hebburn-on-Tyne yard and was dry-docked. The crew were permitted to head into Newcastle for R&R although inevitably monitored by UB agents. As the work was drawing to it’s conclusion in June, Captain Jan Cwiklinski took one such trip into the city. He would not return. Evading his unseen chaperones, Cwiklinski was driven to Darlington and took a train to London where he met a friend. He then went to a local Police Station and asked for political asylum. It transpired he had been tipped off that he was under surveillance and would have been arrested when the ship returned to Gdynia. Ultimately Batory’s former Captain moved to the United States becoming a US citizen in 1960.

Batory continued in service between Northern Europe and the Indian sub-continent in 1954, embarking the Pakistan cricket team in April for its inaugural tour of England (a drawn series) and taking them back again in the Autumn.

It may have been on her return voyage that Batory was struck by two huge waves on 28th October off the Libyan coast. Three crewmen were swept overboard to their deaths and a fourth was fatally injured.

Despite this tragic incident Batory’s future on the Bombay service seemed assured until politics once more intervened. The Suez Crisis precipitated the closure of the canal in November 1956, resulting in a considerable and costly detour around Africa. She made just one of these long and expensive treks via the Cape before Polish Ocean Lines decided to reassign her to a new Atlantic service. The death of Stalin and cessation of the Korean War in 1953 initiated a thawing of East-West relations, and whilst the United States maintained its embargo of the ‘undesirable’ Batory, Canada was more amenable. Before starting the new service the twenty year old liner was sent to Bremerhaven for a comprehensive refit and modernisation. Visually the most significant changes were the repainting of the hull, reverting to black, and the replacement of the original luffing lifeboat davits by more modern, angular gravity davits. Whilst freeing up promenade space and allowing passengers to gaze over the handrails on Boat deck the change inadvertently ruined the ship’s original smart silhouette. Aesthetically it created the illusion that the upper decks had been pushed down into the superstructure, partially obscuring the funnels.

Reflecting the demands of the service she emerged with accommodation for 76 First Class and 740 Tourist Class passengers. Batory departed Gdynia on her first Canadian voyage in September 1957, calling at her original Eastern seaboard interim ports of Copenhagen and Southampton, before taking the Northern ‘Great Circle’ route to Quebec and Montreal. She also frequently called at a regular wartime stopover, Halifax, Nova Scotia. A few years later there would be occasional high summer direct sailings between Montreal, Helsinki and Leningrad.

Despite the general waning of passenger liner services from 1958 onwards the Batory remained an immensely popular ship. With very competitive prices, no direct flying alternative and the promise of an unrestricted baggage allowance, Poles patronised her in their droves. Danes and other continentals had always enjoyed her old world charms whilst for many British and Canadians it was intriguing to sail on a ‘Communist’ liner. Whether or not she was particularly profitable remains a mute point but much of her income was in hard foreign currency which was invaluable to the Polish economy.

Batory also continued off-season cruising, although now in the winter rather than summer months. From 1959 until her withdrawal a decade later this included a long and leisurely annual foray deep into the Caribbean. Roger Emtage, who grew up in Barbados, recalls that she would always anchor for two nights off Bridgetown and on her departure skirted the coast at speed, sending up an impressive bow wave, close to the shoreline to afford her passengers a view of the island, before heading off towards the setting sun and her next destination.

Although Batory‘s crew and passengers doubtlessly encountered the normal day to day trials and tribulations of shipboard life, there appear to have been no dramatic events to recount during that final decade of service. As the competition steadily evaporated from the Atlantic sea lanes she sailed on regardless, gracefully aging like contemporaries Queen Mary and Nieuw Amsterdam and offering a sanctuary to the nostalgic and aerophobic, in the era of the jet age.

Such was her longevity that Batory even witnessed a degree of rapprochement in Polish-American relations. On 29th December 1965 she berthed at Commonwealth Pier, Boston, disembarking a total of 650 passengers, 450 of whom were immigrants from countries east of the Iron Curtain. To many it seemed that the ship would go on for ever but Polish Ocean Lines started to plan for a successor in the mid to late 1960s. Such was her popularity that thought was given to building a new 20,000grt replacement, rumoured to be called Polonia, but escalating costs put paid to such a suggestion. Instead when her hard working machinery finally succumbed to age she was superseded by Holland-America’s former tourist class vessel Maasdam, which was renamed Stefan Batory.

In December 1968 Batory made her 222nd and last trans-ocean scheduled liner voyage, before embarking on a final programme of cruises. On 20th February 1969, dressed overall and still looking resplendent, she arrived at the Tilbury landing stage to become the centre point of an emotional and poignant reunion for many of those children who had fled war torn Britain for Australia on her back in 1940.

Rather than scrap the national flagship she was sold by Polish Ocean Lines (effectively the government) to the Municipality of Gdynia for the grand total of one zloty. She was allocated a permanent berth and in common with her contemporary Queen Mary converted for use as a hotel, restaurant and convention centre. There the similarities ended. Inevitably in an effectively ‘closed’ country Batory never generated sufficient trade to earn her keep. Opened in 1969 the end effectively came in December 1970 when a sudden increase in food prices prompted strikes and protests against the communist regime. On the night of 16th-17th December the port of Gdynia was occupied by police and the Polish People’s Army, with images of a tank stationed next to Batory. The following morning soldiers opened fire on workers coming into the port, killing up to 18 and injuring hundreds.

Sold back to Polish Ocean Lines, Batory was promptly resold to Hong Kong breakers Leung Yau Shipbreaking Co. for $570,000. She departed Gdynia for the last time at the end of March, passing Stefan Batory on 11th April 1971 and arriving at her final resting place exactly one month later.

Even today mention of the sisters evokes strong sentiment in Poland. Their stories are a staple of the school curriculum and in her former home port. Batory is remembered in a special display at the eponymous shopping centre. Many nations revere their ships but few can match the devotion shown to the memory of Piłsudski and Batory.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item