![]() The short lived Egyptian Mail Steamship Co. Ltd. of London ordered two large Edwardian passenger liners with accommodation for over one thousand passengers for the Marseille to Alexandria route for delivery during 1907/08. However, the directors had made the classic mistake of overestimating the potential demand on this route, given that it was operated by the firmly established Messageries Maritimes and the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Co. Ltd. as well as the Khedivial Mail Steamship Line, later majority owned by P. & O. Passengers used these services to avoid the rough sea passage across the Bay of Biscay to the Mediterranean. The powerful P. & O. connected to Marseille from London using its own dedicated company trains, timed to the arrival of their steamers. This overwhelmingly strong competition proved too much for the Egyptian Mail Steamship Co. Ltd. and their service was unprofitable. Heliopolis and Cairo had been launched by the Fairfield yard at Govan in May and July 1907, and completed in November 1907 and February, 1908. The Egyptian Mail Steamship Co. Ltd. was in liquidation by 1909 and Heliopolis and Cairo were put up for sale at Marseille. They had been built at enormous expense and cost a staggering £350,000 each, high for that time, making an investment of £700,000.

The short lived Egyptian Mail Steamship Co. Ltd. of London ordered two large Edwardian passenger liners with accommodation for over one thousand passengers for the Marseille to Alexandria route for delivery during 1907/08. However, the directors had made the classic mistake of overestimating the potential demand on this route, given that it was operated by the firmly established Messageries Maritimes and the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Co. Ltd. as well as the Khedivial Mail Steamship Line, later majority owned by P. & O. Passengers used these services to avoid the rough sea passage across the Bay of Biscay to the Mediterranean. The powerful P. & O. connected to Marseille from London using its own dedicated company trains, timed to the arrival of their steamers. This overwhelmingly strong competition proved too much for the Egyptian Mail Steamship Co. Ltd. and their service was unprofitable. Heliopolis and Cairo had been launched by the Fairfield yard at Govan in May and July 1907, and completed in November 1907 and February, 1908. The Egyptian Mail Steamship Co. Ltd. was in liquidation by 1909 and Heliopolis and Cairo were put up for sale at Marseille. They had been built at enormous expense and cost a staggering £350,000 each, high for that time, making an investment of £700,000.

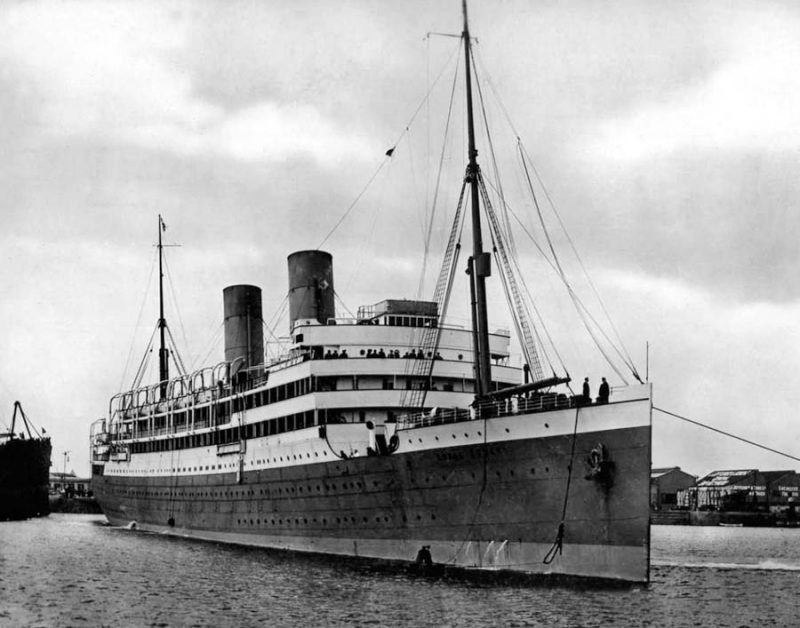

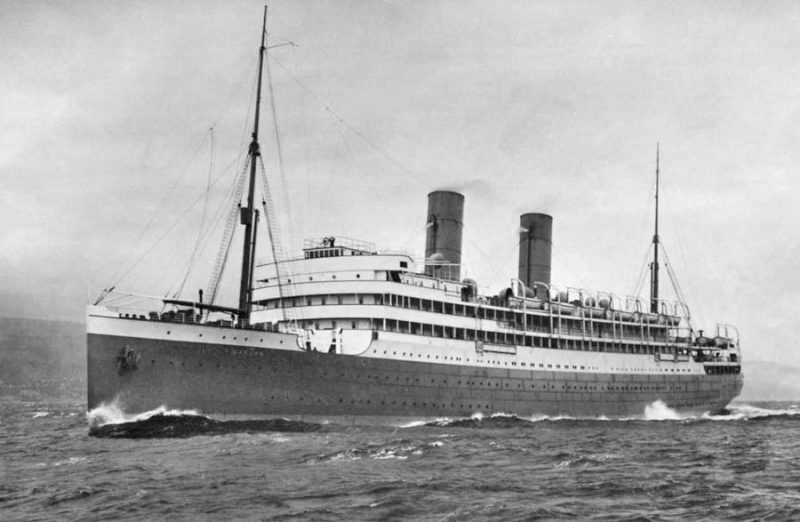

Heliopolis and Cairo were of 545 feet overall length, beam of 60.2 feet and draft of 26.8 feet, with a fo’c’stle of length 70 feet and Bridge Deck of length 308 feet. They had three passenger decks, plus three more decks and a shelter deck with freeboard below the weather deck. They had accommodation for 344 in First Class, 210 in Second Class, and 560 in Third Class giving a total of 1,114. The accommodation and excellent public rooms were lit by electricity throughout, and with hulls with strong transverse web frames, plenty of refrigerated food stores, and the latest safety equipment, they were well designed twin funnelled liners. On trials, both had achieved well over twenty knots, with Capt. G. Gregory taking charge of both liners on their maiden voyages. They flew the Red Duster as they were registered at London.

They had triple screws with three steam turbines fed with steam from four double ended and four single ended boilers at a pressure of 180 pounds to give a high service speed of 19 knots on coal consumption of 170 tonnes per day. This triple screw arrangement was used to avoid cavitation problems, and had been employed for the first time on the North Atlantic on two turbine powered liners, Victorian and Virginian of Allan Line of 10,750 grt and completed in 1905. Sir Charles Algernon Parsons had demonstrated the use of three propellers to avoid cavitation and the consequent decrease in speed in April, 1896, when his pioneer Turbinia was fitted with three parallel flow axial turbines with three propellers on each of three shafts and achieved 35 knots. He followed this a year later at the Spithead Naval Review with a sensational run through the line of warships at the same speed, thus immediately convincing their Lordships of the Admiralty of the power of the steam turbine. Turbinia is permanently on display in the Main Hall of the Discovery Museum in Newcastle upon Tyne.

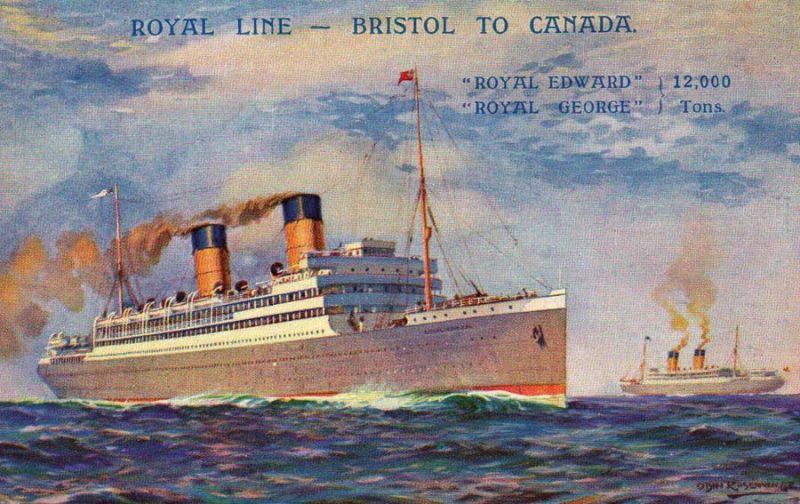

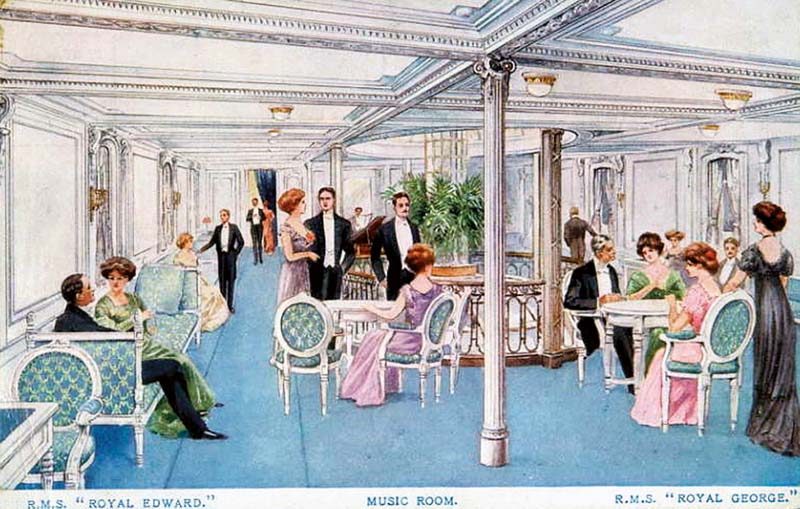

Both liners were seriously unprofitable and after lay up at Marseille they found a new buyer at the end of 1909. This new buyer for Heliopolis and Cairo was the Canadian Northern Steamships Ltd., a subsidiary of the Canadian Northern Railway, established in 1889 at Toronto. They were to be used on a North Atlantic service from Montreal and Quebec to Avonmouth, with Heliopolis renamed Royal George, and Cairo as Royal Edward, and both were registered at Toronto. The company was known as the ‘Royal Line’ because of the royal nomenclature, with their slogan ‘Fastest to Canada’ in order to compete with Cunard Line, Allan Line and Canadian Pacific Steamships. Alterations were made to their top passenger decks by the Fairfield yard for their new North Atlantic service, their gross tonnages increasing slightly to 11,146 and 11,117 respectively. Due to their high speeds, the pair operated a successful service with medium grey hulls and yellow funnels with a black top. They had luxurious public rooms including Dining Rooms, Lounges with cafes, Smoking Rooms, Music Rooms, and well stocked libraries. Royal George sailed on her first voyage from Avonmouth to Montreal on 26th March 1910, followed by Royal Edward on 12th May. At Montreal, it was realised that the sisters coaled through side ports, and a special coal lighter with stump derricks was converted from a tall, vertical grain elevator. There were no problems when the lighter was on the outward side of the vessels, but the liners had to be ‘ranged’ or ‘boomed’ from the quay to allow passage of the lighter between the quay and the ship to coal on the inward side.

They were put through their first Special Surveys during 1912 at Avonmouth and Glasgow respectively. On 8th April 1912, Royal Edward encountered and reported an ice field in the vicinity of the area in which the Titanic sank four days later. On 5th November 1912, Royal George unfortunately grounded on Orleans Island in the St. Lawrence as the ice began to form, and remained aground for two weeks until refloated and temporarily repaired at Halifax. She was fully repaired at Birkenhead by Cammell, Laird & Co. Ltd. from 12th December 1912 during the following six months. When the St. Lawrence was frozen over in winter, the pair operated a fast service to Halifax (NS), except in the winter of 1913/14 when St. John (NB) was used, until they were requisitioned as troopships at the beginning of World War I.

Their main rivals between 1911 and 1914 were the twin funnelled Empress of Britain and Empress of Ireland of 14,190 grt built in 1906 by the Fairfield yard, and the twin funnelled Teutonic of 9,984 grt built in 1889 by Harland & Wolff Ltd. at Belfast. The latter was rebuilt for the joint White Star Line-Dominion Line service in 1911 and transferred to the Canadian route, carrying only Second and Third class passengers from Liverpool. However, Empress of Ireland was sunk with heavy loss of life on 30th May 1914 in a collision with the Norwegian collier Storstad owned by A.F. Klaveness. The Canadian Pacific steamer had left Quebec at 1630 hours the previous day and dropped off her pilot at Father Point on the St. Lawrence at 0130 hours. As she was leaving the pilot station she was in collision in fog with the approaching Storstad, loaded with 11,000 tonnes of Nova Scotia coal, and sank in ten minutes with 1,024 lives lost by 0155 hours. The crews of the ‘Royal’ pair were very saddened by the news, despite being competitors.

In June 1914, Royal Edward was fitted with one of the first wireless direction finders. This was the Marconi-Bellini-Tosi system, the patents for which had been secured by Guglielmo Marconi from E. Bellini and A. Tosi in February 1912. Germany began to move her troops towards the Low Countries on 30th July 1914, with Britain declaring war on 4th August following an ‘unsatisfactory reply’ from Germany to the British ultimatum that Belgium must be kept neutral. Lord Kitchener, the new Minister of State for War, avoided conscription by inviting men to volunteer with their male relatives and friends to form the Pals Battalions, asking for 100,000 volunteers. Liverpool raised four Pals Battalions within days, followed by the Sheffield Pals, Accrington Pals, Tyneside Irish Pals, Hull Commercial Pals, Glasgow Tramway Pals and other Sporting and Work Pals Battalions. The scale of ‘The Response’ was astounding, with half a million men volunteering by mid September and another half a million by the end of 1914. The famous poster showing Lord Kitchener pointing outwards with the slogan ‘Your Country Needs You’ made many more men enlist. In Canada, the response was equally wholehearted, with a force of 33,000 men assembled at Quebec by the end of August as the 1st Canadian Expeditionary Force. They embarked in a big convoy of 32 troopships, including Royal George and Royal Edward, which assembled in Gaspe Bay and sailed on 3rd October with a close escort of four cruisers and two battleships, with another battleship joining later in the voyage, and arrived safely at Plymouth on 16th October 1914.

Sinking Of Royal Edward

Royal George and Royal Edward then spent the next ten months as troopships carrying British troops to French ports. Royal Edward was also briefly used as an internment vessel at Southend for civilians who had been arrested because of their German sounding names. On 28th July 1915, Royal Edward under Commander Peter M. Watton RNR embarked 1,367 officers and men at Avonmouth, and with a crew of 220 and a cargo of Government stores sailed for Malta and Alexandria. A rough trip was made to Gibraltar with many of the troops seasick. The majority were reinforcements for the 29th Infantry Division with men from the Hampshire Regiment, Lancashire Fusiliers, King’s Own Scottish Borderers, South Wales Borderers and a large contingent of the Royal Army Medical Corps to serve in the makeshift field hospitals. Royal Edward arrived at Alexandria on 10th August 1915, with Royal George having arrived there from Devonport on the day before.

Royal George sailed from Alexandria and arrived safely at Mudros Bay on 13th August, the same day that Royal Edward was in a position to the north of the islands of Rhodes and Tilos in the Dodecanese group by 0900 hours. She had also passed the British hospital ship Soudan heading in the opposite direction. However, lurking nearby was the German submarine UB14, commanded by Oberleutant zur See von Heimburg, which had arrived in June, 1915 at its base at Orak Bay ten miles east of Bodrum in Turkey following completion at Pola in Austro-Hungary (now Pula on the Istrian peninsula of the Adriatic) from sections sent overland from the A.G. Weser yard in Germany. Von Heimburg allowed Soudan to pass unmolested, but fired a single torpedo at Royal Edward, which exploded with great force at 0915 hours and completely wrecked her stern. UB14 could only carry two torpedoes and was very limited in range due to poor battery power, but her foray from Orak Bay that day had deadly consequences.

Royal Edward was six miles to the west of the small islet of Kandeloussa, and the situation was desperate with no time to launch the lifeboats as her stern was awash in three minutes and she took her final dive to the seabed stern first with her bow vertical three minutes later. Lifebelts were thrown from the weather deck, with those that survived having to jump into the sea and swim to safety away from the liner. Commander Peter M. Watton went down with his ship, but most of her Navigating Officers survived, plus most of those who were on deck at this time, but a huge number of 935 troops and crew were drowned. The sad reason for this huge loss of life was that all of the troops had previously been lined up on deck for morning inspection and boat drill, and then when the torpedo struck were ordered below to put on their lifebelts, where they were engulfed by the rapid sinking and sloping angle of the decks.

Edward W. Dyer, one of the radio officers of Royal Edward, was able to get off a Mayday call before losing power, and the hospital ship Soudan reversed her course and arrived on the scene at 1000 hours and began rescuing the survivors. Soudan was of 6,680 grt and had been completed in 1901 by Caird & Company of Greenock for P. & O.’s permanent Indian trooping charter. On reaching the location of the sinking, Capt. Gill of the Soudan found that the sea was littered with wreckage and lifeboats, many of which were bottom upwards, to which men could be seen clinging. Many of the survivors were just swimming around or hanging on to anything that could float. Soudan lowered all of her lifeboats and began pulling men from the sea, and she rescued 440 survivors on this very hot day in the Aegean until after 1600 hours. The Blue Funnel Line vessel Achilles of 7,403 grt built in 1900 by Scotts of Greenock rescued 29 survivors, and two French destroyers and some Greek trawlers rescued another 221 survivors, but 935 men and a fine liner had been lost before they even arrived at the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign.

The gallant radio officers of Royal Edward, which was the first British troopship to be lost in World War 1, survived but Edward W. Dyer received leg injuries so severe while struggling in the water that one of his legs had to be amputated. John Keir, the other radio officer, was crushed between two collapsible lifeboats and suffered bruised ribs. The hospital ship Devanha left Alexandria immediately after the news of the sinking was received. A memorial service was held at the exact position of the sinking at the suggestion of her Master. Lifeboats, lifebelts, soldier’s water bottles, planks and other pieces of wreckage were strewn all over the position of the sinking. Devanha’s ship’s bell tolled slowly while the crew assembled on the Boat Deck to pay their last respects to the dead. The Master, Navigating Officers, Engineers, Stewards plus all of her medical staff of doctors, nurses and orderlies of the Royal Army Medical Corps began the service with the hymn ‘Let Saints on earth in concert sing’, followed by the opening sentences of the Memorial service and the 46th Psalm – God is our help and strength. The lesson was read and the committal prayer said for those lost at sea. Prayers were then said for all those in anxiety and sorrow including all the soldiers and sailors of the Royal Edward. Devanha then slowly picked up speed for Mudros after the final blessing, hymn and National Anthem.

The troopships that were following Royal Edward were diverted away from the Kos island area of the Dodecanese islands. Measures were taken to strengthen the British naval presence in the area where two German U boats were known to be operating off Kos. The transport Manitou of 6,849 grt carrying British troops to Mudros Bay had earlier been attacked on 16th April 1915 in the Aegean by a Turkish torpedo boat which fired three torpedoes, all of which missed. The Turkish vessel was then chased by the British cruiser Minerva and some destroyers and was finally run ashore and destroyed in Xalammuti Bay on Chios. The Turkish crew was taken prisoner, but unfortunately there was a loss of life of eight men when a lifeboat capsized from the Manitou. A year after the sinking of Royal Edward, the giant four funnelled hospital ship Britannic, sister of Olympic and Titanic, was mined and sunk on 21st November 1916 in the Zea Channel off the island of Kea in the Western Aegean while en route to Mudros with the loss of 21 lives from 1,134 people on board. Britannic was the largest ever British Merchant Navy war loss.

Final Years Of Royal George

The surviving sister, Royal George, made other voyages through the Aegean to Mudros Bay from Marseille with troops after the sinking of her sister. The Gallipoli campaign had begun on 19th February 1915, was aborted during December 1915 with the last troops evacuated on 8th January 1916. Royal George also trooped from Durban to the Persian Gulf, but later in 1916, her owners, the Canadian Northern Steamships Ltd., were taken over by Cunard Line.

Their other vessels were also taken over by Cunard, Uranium, Principello, and Campanello, formerly of the Uranium Steamship Company, which was an extension of the Northwest Transport Line from 1910 and owned by the Canadian Northern Railway Company. The fourth vessel of the Uranium Steamship Company, Volturno, had already been lost by fire in the North Atlantic. She was of 3,581 grt and had been completed in 1906 by the Fairfield yard as an emigrant steamer and had three different owners up until 1910. She left Rotterdam on 2nd October 1913 with a very flammable cargo of barium oxide, several other chemicals, rags and straw bottle covers as well as 561 passengers and 96 crew. A week later, thick smoke was seen coming out of number 1 hold and roaring gale force winds helped to fan the flames over the rest of the vessel. Three liners and seven other ships picked up 521 passengers and crew from the lifeboats, but Volturno sank the following day with the loss of 136 lives.

The Denny built Uranium of 5,254 grt had been completed in 1891 as Avoca for British India Line, and was renamed Feltria by Cunard and later became a war loss when torpedoed and sunk by UC48 on 5th May 1917 eight miles off the south east coast of Ireland near Mine Head in Waterford with the loss of 45 lives including the Master. Campanello of 9,285 grt had been built by Palmers at Jarrow in 1902 as British Empire, but passed to Italian owners in 1907 and was renamed Campanello by Uranium in 1911, and also became a war loss as Flavia of Cunard on 24th August 1918 when she was torpedoed and sunk 30 miles WNW of Tory Island in Ireland by U107 with the loss of one life. Principello of 6,704 grt had been built by Laing at Sunderland in 1907 as Principe de Piedmonte for Lloyd Sabaudo of Italy, and was renamed Folia by Cunard and also became a war loss when torpedoed and sunk four miles ESE of Ram Head off County Waterford on 11th March 1917 with the loss of seven lives. Cunard Line had used these ships in cargo only mode, but these Uranium Steamship Company ships had been intermediate passenger and cargo ships that ran from Rotterdam to New York. Principello and Campanello had in fact taken over the Canadian passenger service from Avonmouth from Royal George and Royal Edward when they were requisitioned as troopships.

Royal George had by the end of the war acquired her nickname of ‘Rolling George’ from her troops due to being top heavy, and after a post war refit she made her first sailing for Cunard from Liverpool to New York on 8th February 1919. She was now resplendent with a black hull and Cunard red and black funnel colours and under the command of Capt. W. Prothero. Cunard reduced her rolling by removing some weight from the top passenger deck by lowering her lifeboats by one deck onto slung davits. Cunard then took delivery of their famous ‘A’ class and other big new liners during the early 1920s, and Royal George was no longer needed by 1921, and was relegated to a depot ship at Cherbourg for emigrants awaiting passage. She was then laid up at Falmouth, and in July 1922 she was sold for breaking up at the German Naval Base of Wilhelmshaven, and arrived there on 7th August after an interesting but short career of only fifteen years.

There have been other ships with the ‘Royal’ names of Royal George and Royal Edward e.g. the 18th century British warship Royal George named for the monarch George II when launched in 1756 and completed three years later to fight the French. She was the largest warship in the world at over 2,000 tons displacement when launched, and was lost off the south coast of England in 1839. The pair of Edwardian liners with these names under review were worthy ships that had a very bad start to their careers, but then achieved success on the North Atlantic and as troopships.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item