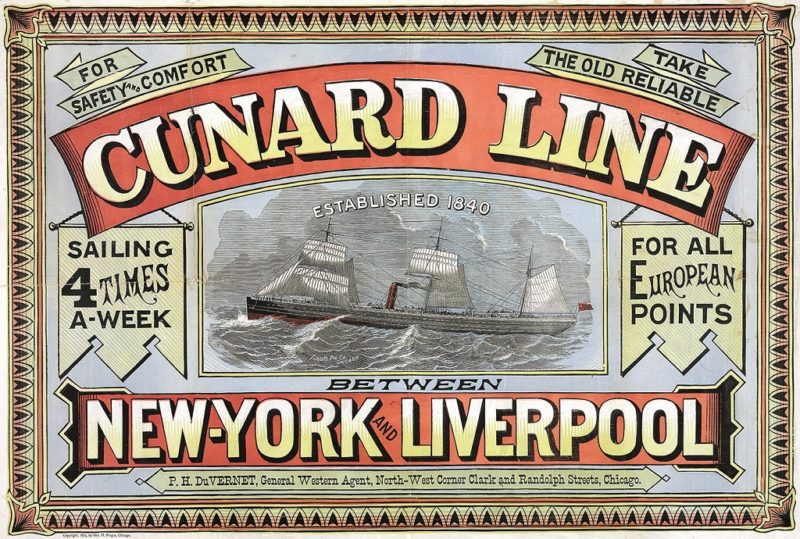

If ever a name is synonymous with passage by ocean liner it is Cunard. To the public at large it conjures images of a quintessentially British institution, of luxurious leviathans steaming at speed across the turbulent Atlantic, whilst their pampered passengers are indulged, enjoying fine dining in opulent interiors. All exudes sophistication. In truth the origins of both the founder and his fleet are rather more nuanced.

Samuel Cunard was born on 21st November 1787, a Canadian of German American and Irish American extraction. On his paternal side, the Kunders had emigrated from Germany and settled in Germantown, Philadelphia in 1683, their name being progressively anglicised over the subsequent century. Historically the family’s Quaker faith was both the cornerstone and cause of their itinerant life, escaping religious persecution a persistent subtext.

Perhaps inevitably Samuel Cunard’s parents met onboard a ship. The circumstances were familiar, although on this occasion the migration was enforced by political rather than religious persecution. Twenty seven year old Abraham Cunard had been a successful shipowner and timber merchant in the colonies, but as a staunch loyalist his assets were confiscated by rebels in the aftermath of American Independence. Financially ruined, in 1783 he and his family embarked on one of a fleet of twenty vessels taking loyalist families from New York to the sanctuary of Canada. On board the same ship was Margaret Murphy, two years Abraham’s junior, travelling with her parents and family.

The Cunards settled where they made landfall in Halifax, Nova Scotia, whilst the Murphys moved inland. Nevertheless, the romantic attachment forged on that voyage evidently remained strong and the two were duly wed and settled in the provincial capital. Abraham secured work plying his original trade as a foreman carpenter and joiner at the local naval dockyard, and by the turn of the century he was appointed master carpenter of the Royal Engineers at the Halifax garrison. Simultaneously he developed a successful timber business and acquired local real estate for rental.

Samuel was the second of Abraham and Margaret’s nine children. He attended Halifax Grammar School, but entrepreneurship was clearly in his genes, selling produce from the family garden to local stores from a young age. He was first employed as a civilian clerk at the local garrison office, doubtless helped by his father’s connections. The job provided a sound grounding but as he later reflected to his daughter Jane, working for the government, “Frequently lead to old age with a small pittance but little removed from poverty”. The ambitious Cunard moved to Boston aged eighteen and secured an apprenticeship with a shipbroker, honing the exceptional organisation and numeracy skills for which he became renowned. Buoyed by the experience the twenty one year old Samuel returned home in 1808 and persuaded his father to establish a new shipping and timber venture. Abraham Cunard & Son was formed.

Whilst his brothers went to sea, Samuel and his father looked after the operation in Halifax. Cunard junior’s astute business acumen, not to mention hard work, soon paid dividends. Early on the firm acquired a captured American vessel and its prize cargo, which capitalised the new venture.

Subsequently they purchased swathes of forest in Cumberland County and sold the resulting timber to both the army and British merchants. Soon the fledgling company was making handsome profits and investing in new tonnage, its ships predominantly sailing to and from the Caribbean region.

Samuel Cunard can sometimes appear to be a man of contradictions and an example of this dichotomy came during the War of 1812. Even whilst serving with the 2nd battalion of the Halifax Regiment of militia, in which he rose to the rank of Captain, he negotiated and secured a license from Governor Sherbrooke to trade with ports in the enemy United States. In 1813 the company purchased the White Oak which sailed for London “with good accommodation for passengers”. Cunard’s fledgling transatlantic service had been inaugurated.

Cunard was soon regarded amongst the pre-eminent shipping companies in Halifax. Its forty ships lined the wharfs, offloading a varied assortment of produce from the West Indies including molasses, sugar, coffee and rum, before sailing south with a rather less exotic cargo of dry and pickled fish, hoops and staves, mackerel, alewives, codfish, timber, and oil. The firm also secured an Admiralty contract for transporting the mails by sailing packet, from Halifax to Boston and St. Johns (Newfoundland). It was a portent of greater things to come. Already a man of wealth and status, in 1814 the 27 year old Samuel married Susan Duffus, the somewhat dowdy (if reports are to be believed) daughter of a prominent local tailor. They would subsequently have two sons and seven daughters.

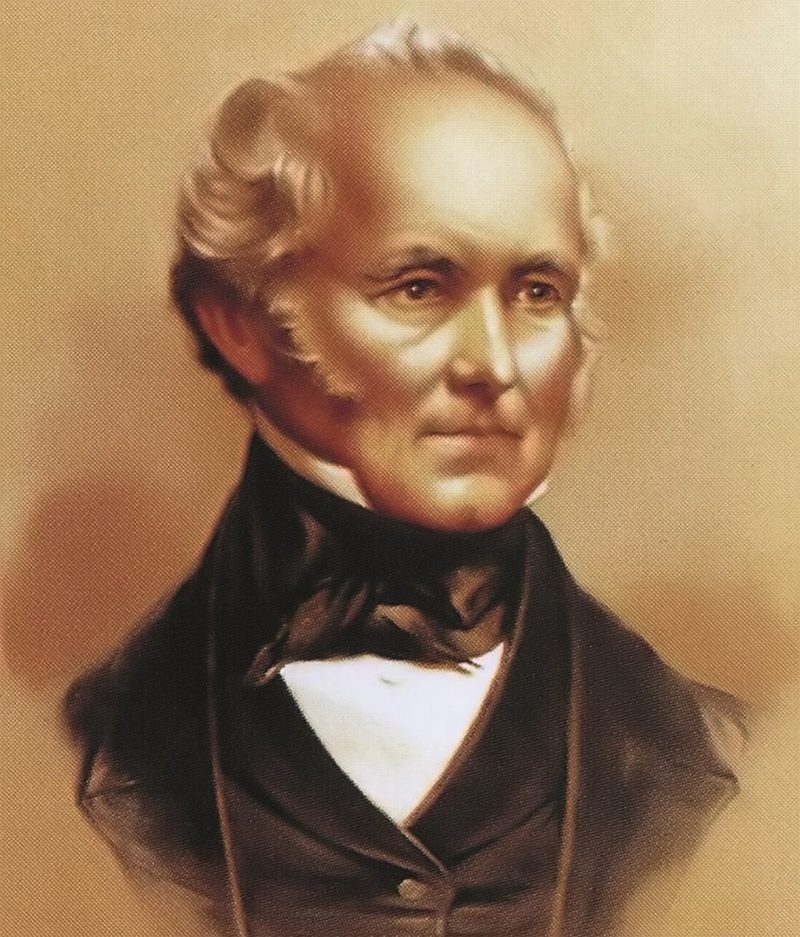

So, what kind of person was Samuel Cunard? Short seems to be an instant response, or “somewhat below middle height” as a fellow Haligonian more sympathetically referred to him. There was a certain pomposity of manner, especially in his formative years. “A bright, tight little man with keen eyes, firm lips and happy manners”, he was reputedly “vigorous in frame, brisk of step, brimful of energy with exceptional nerve force and great powers of endurance, and always on the alert”.

A renowned workaholic Cunard demanded the same level of commitment from his employees and was widely known for his frugal nature, legendary attention to detail (micromanagement in modern parlance) and conservative attitude regarding the adoption of new technologies. He was extremely competitive, a pushy and shrewd negotiator but there was altruism to temper this hardnosed business persona. In the winter of 1817 with recession biting Cunard and another prominent businessman Michael Tobin provided soup kitchen facilities for Haligonians on the brink of starvation.

Cunard was certainly socially adept and quickly became prominent in Halifax society, holding numerous positions over the years. He was a member of the Athenaeum, president of The Halifax Steam Boat Company and (to which he was especially devoted), Commissioner of Lighthouses on the Nova Scotian coast, which he first attained back in April 1816. In February 1809 he gained membership of the exclusive Sun Fire Company, a local organisation as famous for their elaborate balls and festivals as their fire-fighting prowess. Perhaps inevitably his prominence in business circles spilt over into politics. A lifelong Tory, Cunard was proposed then later withdrew his candidature from the local assembly elections of 1826 but was appointed to the Council of Twelve in November 1830, a role dating from the early eighteenth century to advise the Governor, deliberate over bills and act as a civil court of appeal. For the next few years, he dutifully attended both executive and legislative committees, but Reformers railed against the concentration of power and influence amongst the wealthiest and most prominent men in Haligonian society and a decade later, on 1st October 1840 he resigned.

All this lay in the future when, counterintuitively, the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 heralded a period of economic and social uncertainty. The withdrawal of the military from Halifax engendered a reduction in trade and increased unemployment but despite these negative portents the Cunard company continued to prosper, buying up abandoned real estate for bargain prices and using their widespread connections amongst the remaining senior officers to increase procurement services.

By the turn of the decade Samuel had become nominal head of the family and its business. Following his mother’s death in 1821 his father’s involvement reduced even further and the following year Abraham retired and moved permanently to the family’s country estate in Pleasant Valley. He died on 10th January 1824 and was buried alongside Margaret at St. Paul’s churchyard in Rawdon.

The newly formed S. Cunard & Company was established on 1st May 1824, continuing the core businesses of shipping and forestry but with further diversification. Cunard had already made a foray into whaling, (the brig Prince of Waterloo operated in Brazilian waters from 1819 to 1821) but also Iron extraction and smelting (the Annapolis Iron Mining Company). Other investments followed including a stake in the wonderfully named Shubenacadie Canal Company and on 1st September 1825 he put forward £5,000 of the £50,000 initial capital to establish the Halifax Banking Company. In January 1826 Cunard proposed leasing the Cape Breton coal mines, but this never materialised. He did however secure the lucrative contract to provide wharf and warehousing space for the General Mining Association.

Undoubtedly one of the most prestigious and successful of Cunard’s ventures at this time was obtaining the local tea agency for the Atlantic Provinces from the famed East India Company. Shipped directly from Canton to Cunard’s Halifax warehouse, Samuel himself presided over the first of what became quarterly public auctions in June of 1826. The company also re-exported the valuable commodity to the West Indies and other Canadian provinces.

Despite this broad panoply of enterprises, Samuel Cunard’s core businesses remained shipping and ship supplies. He was intrigued but initially unimpressed by the new steamship technology. Savannah’s laborious twenty six day transatlantic crossing in 1819 failed to spike his interest and nor did the numerous steam driven river and coastal craft proliferating along the eastern seaboard. As late as 1829, when prospective partners from Pictou sought his involvement in a project he wrote, “We are entirely unacquainted with the cost of a steamboat and would not like to embark in a business of which we are quite ignorant”.

That attitude soon changed. Cunard quickly saw the merits in a propulsion system that unlike wind was not dictated by nature’s whims and in 1830, with more favourable subsidies on offer, he subscribed to shares in the Halifax Steam Navigation Company. Samuel and his fellow investors were underwriting the construction of Royal William, a vessel designed to link Quebec and Halifax as part of a broader transatlantic mail service. He monitored every aspect of the Royal William’s performance, doubtless informing later decisions, but the service failed due to a cholera epidemic and the resulting quarantine of the ship. Ill-maintained over the subsequent winter her owners went bankrupt and the vessel sailed to Europe where she was subsequently sold, ending her days with the Spanish Navy.

At the age of forty Samuel Cunard was a highly influential man, one of a select group of young Nova Scotians who were slowly replacing the established ‘old guard’ of merchants of his father’s generation. Nevertheless, the company’s prospects looked less than rosy by the mid 1830s, the West Indian trade had diminished due to competition from the United States and a depression every bit as intense as its 20th century equivalent hung over the Canadian economy. Timber had been a mainstay of the Cunard business since its inception but around this time it almost brought the whole edifice down. Much of the blame can be placed on the shoulders of Samuel’s younger brother Joseph. Subsidiary J. Cunard and Company initially expanded rapidly and profitably on the banks of the Miramichi river, diversifying from pure lumber into brick making, fisheries and even shipbuilding. However, it was a capital intensive business and the younger Cunard shared none of his brother’s pragmatism, draining the coffers to maintain an ostentatious lifestyle. When the market collapsed the creditors came calling.

In January 1838 and by now a wealthy 50 year old widower, Samuel accompanied Joseph and his son William to England, where he became involved in a scheme to purchase 60,000 acres of land on Prince Edward Island. All the talk in maritime circles was about the impending sailings of Sirius and Great Western. Eleven months later the British Admiralty advertised for tenders to carry the mail from England to New York via Halifax. There would be a feeder service to Boston. By the time Cunard became aware of it the closing date had passed but as providence would have it neither of the bids submitted impressed the Admiralty.

So it was that in January 1839 Samuel Cunard embarked for Falmouth on the packet Reindeer, armed with a letter of introduction from the Nova Scotian Lieutenant Governor Sir Colin Campbell and plans for his own “ocean railway”. Having weighed up the requirements Cunard submitted a formal bid on 11th February 1839, proposing three 800 ton vessels utilising 300 horsepower engines to meet the stipulated fortnightly departure from each terminal port (being Liverpool and Halifax). In return he sought a 10 year contract and an annual subsidy of £55,000.

His next task was to find a builder for the requisite ships and so he enlisted the help of James Cosmo Melvill, Secretary of the East India Company in London, setting in motion a serendipitous sequence of events. Melvill introduced Robert Napier, arguably the finest exponent of the still novel steam engine technology based at the then epicentre of steamship construction, Scotland’s River Clyde. Napier introduced James Donaldson, a wealthy local cotton broker and Donaldson in turn consulted George Burns, a well-respected and connected shipping man with interests in Glasgow and Liverpool and who would nominally supervise the building and financing arrangements. Burns was highly influential in securing investment in the proposed project as well as introducing Cunard to young David MacIver, a dynamic fellow Scot who Napier had in mind to manage day to day operations of the new steamships. Burns, MacIver and their brothers, together with a broad range of acquaintances invested in the new enterprise, but by far the biggest individual stake of £55,000 was held by Samuel Cunard. Collectively they formed the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, although even in its infancy the business was referred to as Cunard Line.

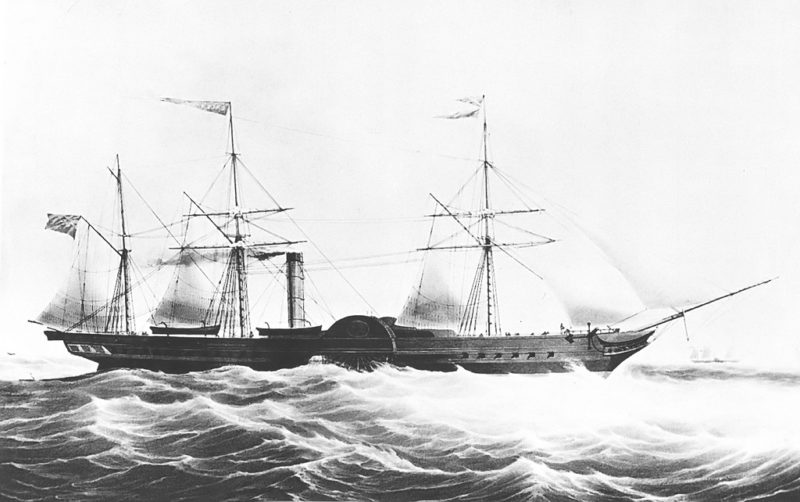

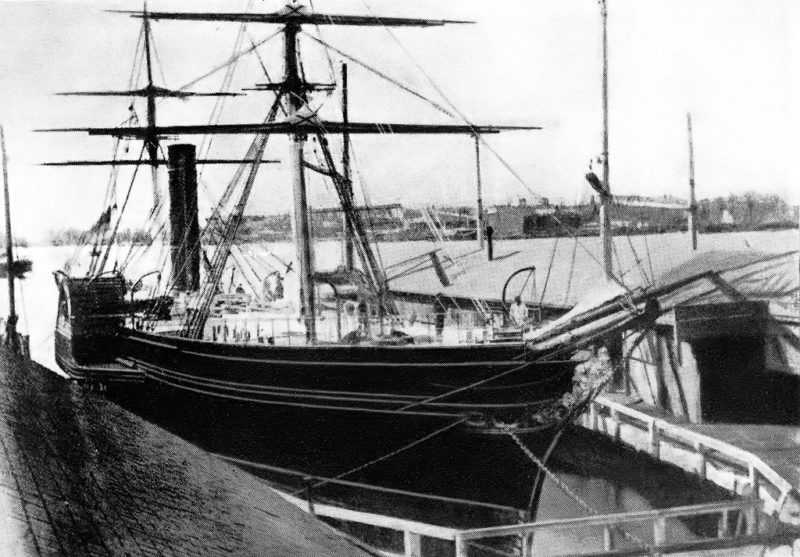

As well as the basic technical detail, Samuel Cunard’s succinct brief to Robert Napier included the prosaic lines, “I shall want these vessels to be of the very best description, plain and comfortable, not the least unnecessary expense for show”, when he commissioned the famous Scotsman to design and build his first vessel in March 1839. Napier, who concentrated on the engines and subcontracted the hull construction to Robert Duncan at Cartsdyke East, subsequently advised that the ships should be both larger (1,100 tons) and more powerful (420 horsepower) than Cunard’s original brief. Persuasive as ever Samuel returned to the Admiralty with fresh proposals, offering an extended service to Boston. On 4th July 1839 a fresh contract was signed with an increased subsidy of £60,000 Despite Napier’s subsequent enhancements, resulting in a larger, more powerful ship and power unit to fulfil the contract requirements, Britannia undoubtedly met Cunard’s original brief in one respect. There was little in the way of luxurious embellishment.

With a length of 204ft (62m), a beam of 32ft (10m) and a gross tonnage of 1,154, Britannia was tiny by modern standards. Amongst contemporaries, whilst certainly impressive, she was not the largest steamship afloat (even the pioneering Great Western was almost 25% larger) but this mattered little to Cunard and his associates. Fulfilling the mail contract whilst avoiding punitive fines for any delays were all that mattered to them. To this end Napier had designed, at his own expense, a cylinder side lever engine producing 740hp which could drive the new vessel at 9 knots. Punctuality with the mail was really all that mattered, passengers were largely an afterthought although Britannia could carry 115 in Saloon Class.

David MacIver was nominally in charge of operations but Cunard still issued a series of draconian memos, instructing Captain Woodruff that, “It will be obvious to you that it is of the utmost importance ….. that she attains a Character for Speed and Safety”. In a typically controlling manner, Cunard then provided a range of detailed advice, “We trust in your vigilance of this, good steering, good lookouts, taking advantage of every slight of wind and precautions against fire are principle elements”. Efficiency was the predominant watchword with a rigid timetable of instructions for everything from stateroom cleaning, commencing at 5am each day to bar opening, at the equally astonishing 6am, through to sheet changing, every 8 days. Nothing was to be left to chance.

On 4th July 1840, Britannia received a tumultuous send-off as she left Liverpool headed out of the Mersey and endured notably tempestuous seas on her passage west. Samuel Cunard was onboard, together with his daughter Ann, her companion and a number of dignitaries including the Lord Bishop of Nova Scotia. There were 63 passengers in all. She reached Halifax in twelve days and ten hours (at 2am) and after an eight hour layover made for Boston, where Cunard was showered with praise, an endless stream of dinner invitations (1,873 in all) and ‘the largest cup in existence’, a thirty inch tall silver cup that now adorns Queen Mary 2.

In 1842 Britannia was immortalised in print. Charles Dickens embarked on his first tour of the United States in January that year, boarding the Cunard steamer at Liverpool. The subsequent book, ‘American Notes’, proved controversial and did not sell well, but for maritime historians the first two chapters provide arguably the finest and most humorous description of a trans-ocean passage ever penned. Combining his usual sharp wit, keen observation of human frailty and vivid scene setting, Dickens paints a picture that resonates even today, and allows the reader to experience each element of that winter crossing in intricate detail.

Of Britannia, Dickens describes the ‘state-room’ he shared with his wife as, “an …utterly impractical, thoroughly hopeless and profoundly preposterous box”. His bed consisted of “a very thin quilt, covering a very thin mattress, spread like a surgical plaster on a most inaccessible shelf”. In a later passage he sanguinely refers to the bunks, “One above the other, than which nothing smaller for sleeping in was ever made except coffins”. The salon he considers, “not unlike a giant hearse with windows in the sides, having at the upper end a melancholy stove”. Dickens’ description of the voyage itself candidly portrays both the terror and comedy of transatlantic passage at the time. Quite what Samuel Cunard and his partners thought of Dickens’ account is unknown but just two months after Dickens’ westbound crossing the Cunard had problems of his own.

Despite being one of the wealthiest men in Nova Scotia, Cunard’s investment in steamships and land overstretched his finances and he was forced to clandestinely board one of his own steamers from a rowing boat to escape the clutches of British creditors in March 1842. Through a combination of mortgages and loans the creditors were kept at bay, nevertheless Cunard and his fellow investors found that the costs of running the steamship mail service far outstripped the original operating subsidy. They duly petitioned for and secured an increase to £81,000 per annum but on condition that a fifth vessel was added.

Aside from Dickens’ passage the single most famous event in Britannia’s brief Cunard career came two years later when she was entrapped by ice at her Boston Wharf. Cunard’s decision to select Boston rather than New York as his western terminus had endeared him and his vessels to the Massachusetts city and so concerned were the local elite that Cunard’s allegiances might shift to their southern rival that they convened an extraordinary meeting and devised a plan to extract the vessel from her slip. Under the Mayor’s direction a posse of local businessmen and shipping merchants raised the necessary funds and contracted ice ploughs to cut a 200ft wide channel to the ocean. On 3rd February 1844, accompanied and cajoled by a large crowd of running, skating and cheering Bostonian’s, Britannia edged away from her pier and steamed at 7 knots to Halifax and Liverpool.

The euphoria of Britannia’s escape from Boston ice was perversely matched almost exactly four months later when the company’s Columbia foundered in dense fog on Seal Island on 1st July 1844. The loss of the ship was of course a tragedy but crucially all the passengers were safely rescued. Such good fortune secured Cunard’s legendary reputation for safety.

Against, almost certainly legitimate, cries of unfair competition from those at the Great Western Steam-Ship Company, in 1846 Cunard negotiated and secured a ten year extension to their admiralty contract and an increased £145,000 subsidy, to provide an alternating mail service to Boston and New York, weekly between March and October and bi-weekly over the winter months. Cunard’s connections at the Admiralty and even at the core of Government effectively eliminated all rivals.

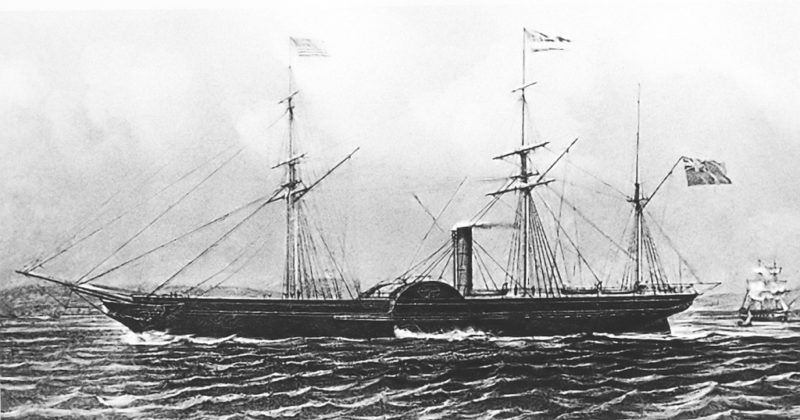

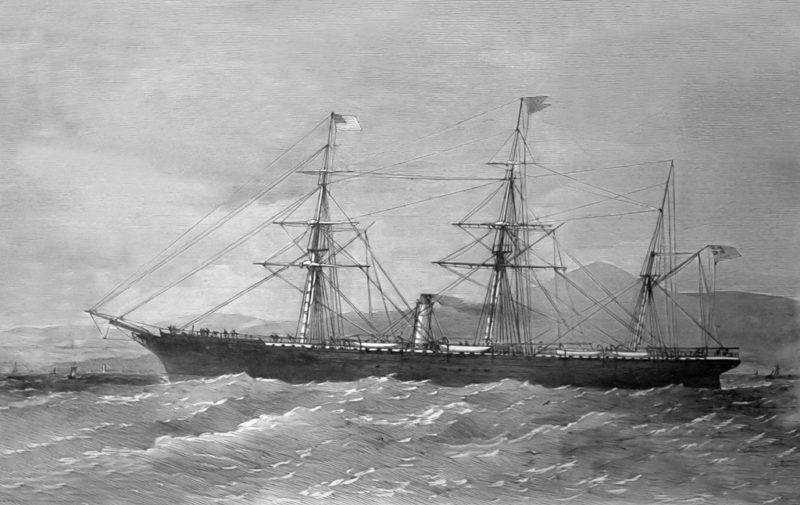

Although one of the original quartet, Hibernia, made the first sailing from New York on 1st January 1848, maintaining the new service required larger and more powerful vessels. Once again Robert Napier designed and built the requisite engines whilst sub-contracting construction of the hull for the new vessels, America, Niagara, Europa and Canada.

By the start of the following decade Cunard was spending increasing amounts of time enjoying London society. The steamship line’s chief rival at this time was Collins Lines, whose eponymous founder was an ebullient American, bankrolled by a piqued US government. Collins’ ships were larger, faster and more luxurious than Cunard’s, securing a high proportion of the Liverpool to New York passenger trade. They were also considerably more costly to build and maintain in service. Nevertheless, acknowledging his rivals pre-eminence, Cunard compromised his conservative ideals and ordered an iron hulled vessel three times the size of Britannia, with engines five times as powerful. Persia swept the ocean with the fastest Atlantic crossing, perhaps for the first time transforming Cunard’s reputation from slightly dour practicality to speed and luxury. When misfortune led to the loss of two Collins steamers in quick succession, Arctic in 1854 and Pacific in 1856, the US Congress withdrew their support and in 1858 Collins was bankrupted. Cunard’s hegemony was maintained.

Cunard may have been taking more of a back seat in the business, but the company’s operations continued to spread under the dynamic stewardship of Liverpool partner Charles Maclver, brother of David. There was further expansion into the Mediterranean and the service to Gibraltar, Malta and Istanbul which started in 1853 became an increasingly prominent part of the Cunard business. It was primarily founded on the emigrant trade from Southern Europe to the United States.

Cunard may have indirectly seen off the Collins threat, but as the 1850s progressed further competition emerged in the form of Inman Line, Anchor Line and Allan Line. Cunard’s Admiralty connections continued to give the company an edge in mail contract negotiations but his reticence to adopt proven technology frustrated Burns and MacIver. Not until 1862 did the company introduce its first screw driven vessel, the 2,638 grt China.

On 9th March 1859 Samuel Cunard was knighted for his services to trade and in recognition of the line’s considerable contribution (11 troop transports and two hospital ships) to the Crimean war effort between 1853 and 1856. He lived out his later years mainly in London having relinquished control of most of his Halifax business interests to his son William.

Twenty five years after the shipping line that bore his name founded, Sir Samuel Cunard, a Baronet no less, died at his Kensington home on 28th April 1865. His legacy stood the test of time and despite setbacks and changes of ownership, Cunard passenger vessels have remained in transatlantic service ever since.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item