Neil Thomson Semple, 1917 to 1932

These memoirs of my Uncle, who was born on a Kintyre hill farm in 1900, were kindly lent to me by his daughter Patricia Semple. Upon reading them it became apparent to me that the story he told was of a breed of men now largely forgotten, but who performed important work at sea until technology finally overtook them. These memoirs extend to nearly four hundred pages, and with the permission of his daughter, I have selected and edited some highlights of his most interesting story.

John Martin

First trips 1917, the Scandinavian and the Celtic

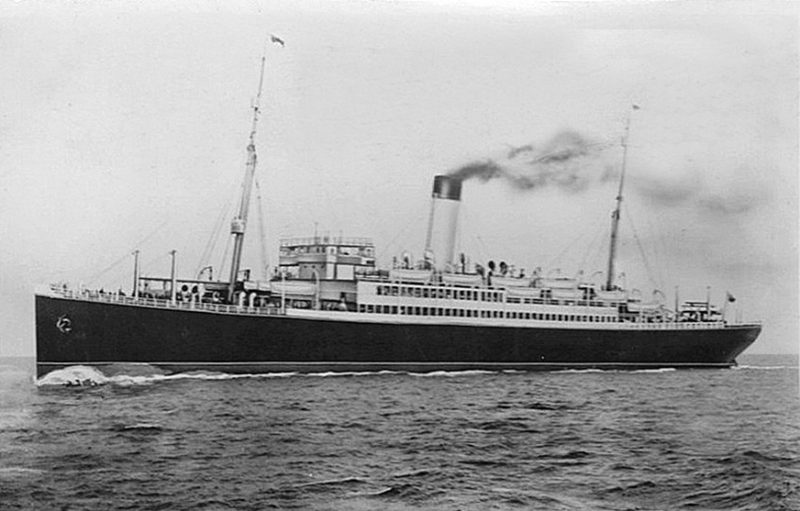

My first ship was the Scandinavian, a moderately large passenger vessel of the type running on the North Atlantic at the beginning of the century. She belonged to the now defunct Allan Line of Glasgow, and was at that time in the process of being taken over by the new owners, the Canadian Pacific Railway Co. They called their shipping line the Canadian Pacific Ocean Services at that time and did not rename the Allan Line ships until after the 1914-1918 war. I joined the Scandinavian in Liverpool early in May of 1917, at which time the submarine campaign was at its height, and, although I do not remember many details of the vessel, I loved her from the start.

She had one extraordinary feature which I never saw again in the many ships on which I served subsequently. Her main deck was flush fore and aft and the navigating officers’ accommodation was on an island forward of the bridge and under the foremast, while the Wireless Room was perched on top of this structure. In an Atlantic gale the whole house was like a half-tide rock and, as the berths of the two Radio Officers were deep down in the 2nd Class passenger accommodation, it was quite a hair raising experience going on watch at 2.00 A.M. on a stormy night in the blackout. It was a situation which could not arise today because safety regulations now call for the Radio Officer to be housed near his place of work. On the Scandinavian it is most unlikely that the off-watch Radio Officer would ever have been able to reach the wireless room in a bad emergency. However, those things worried me not at all in those far-off days. I loved the ship and everything about her.

For a homesick and very young Scotsman there was a preponderance of good fellow country men aboard and, as I remember, the navigating officers were all Scots including the Captain, a God-like being to whom I never had the opportunity of speaking. The Captain’s name was Reith, and the Chief Officer was a short, rather dumpy and pompous looking man whose name escapes me, but whose nickname was Napoleon and whom he resembled to an extraordinary degree. The First Officer was Mr. Beaton, and I also recall the newly promoted from cadet to 4th Officer McGirr, a rather ‘gallus’ type Glasgow lad with a heart of gold. We were good friends from the start and I have never forgotten him although I never saw him again after l9l7.

There were some extraordinary types in the catering department which is always the biggest on passenger ships, The Chief Steward, old Archie Stewart, well known on the North Atlantic and a man who always reminded me of a Turkish pasha when he sat in his room dispensing rough justice on his minions and issuing orders. The Chief Steward was a man of great power on any passenger ship but, for some strange reason, without officer status. Then there was Monkhouse the 2nd Steward and Bob Hunter the chief storekeeper, both great humorists and jolly good chaps. Hunter was especially kind to me and I used to visit his vast food storeroom in the bowels of the ship whenever I had a chance. While Bob worked at his accounts I never got tired of exploring this veritable Aladdin’s cave. Bob Hunter had married the daughter of the then Chief Engineer of the Campbeltown steamer ‘Davaar’, and this made a bond between us. Between voyages I spent some happy hours at their home in Egremont on the Wallasey side of the Mersey.

The Chief Engineer, old Jimmy Walker, was also a Scot and very typical of his profession, a dour but thoroughly likeable man. Of the other engineers on board I have literally no recollection at all and I find it hard to explain this. Of course, engineers on those old time Atlantic liners were housed in what was known as the ‘working alleyway’, a kind shipboard slum at the top of the engine room. They were seldom seen during the sea passage as they had their own messroom and spent many hours a day clad in boiler suits. It is a fact that in the old coal burning passenger steamers, the more junior engineers were little better than stokehole slave drivers. Together with their slaves, the old time Liverpool type firemen and trimmers, they worked desperately hard to maintain the necessary head of steam developed by multiple marine boilers needed to allow the ship to keep her schedule, and when off watch spent most of their time asleep. This hardy breed has long since disappeared from the scene, but the memory of the hard fighting, hard drinking and equally hard working men from Scotland Road vividly remains. In the case of the liner navigating officers, also of the more senior engineers during the era prior to 1920, it seems to me that they were invariably men in middle age or older. Promotion was slow in those days of individualistic shipping companies each with its own traditions and orderly seniority lists. Command or promotion to Chief Engineer was something that came with age and experience, and if a man could put in ten years as Captain before retirement he was lucky. But with it all there was a deep impression of professionalism and integrity. They were dedicated men who were sadly exploited by their employers.

The Scandinavian was built in 1898 as the New England for the Dominion Line and later, in l905, had been taken over by the White Star Line and named Romanic. She ran for the new owners until 1912 when the transfer to the Allan Line took place, after which she was given her final name. A good looking but rather slow (15 knots) vessel her career was quite successful considering the fact that she ran the gauntlet of the North Atlantic throughout the First War without incident. Oddly enough, despite her slowness, she was given some very important tasks at this time. During my two voyages on her, she was full each way on the Liverpool to Montreal run with passengers and Canadian troops. She was not requisitioned but was several times given an auxiliary cruiser escort to herself and did not sail in convoy in my time. In the vicinity of Cape Race in May 1917 gunnery practice by our 6 inch gun was carried out on an iceberg without much damage being done. The Returning Canadian troops were mostly invalided-out men and were an interesting bunch.

Radio silence was maintained throughout the voyage except for some relaxation in the St Lawrence River above Fame Point. It was a thrill for me to watch for the first time a radio-telegram being transmitted by a one and a half Kw fixed spark transmitter, the noise was appalling but very satisfying to our itchy fingers. We had been compelled during the eight days passage from Liverpool to listen only and maintain a log book recording all important signals heard. In those days a lot of them were distress calls from torpedoed ships or requests for assistance from ships being ‘gunned’. One such call I remember to this day – “SOS SOS SOS 45.40N 55.27W Kumara gunned”. Terse, and very much to the point.

We listened enviously to neutral passenger ships belonging to Norway, Holland, Spain and some others using their transmitters normally as it was still peace time with them. One in particular was the Bergensfjord of the Norwegian Line which always seemed to have a full file of telegrams for the various Canadian and American land stations. The Spanish liners also were very much in evidence, particularly the Alfonso XIII, which had the most powerful set built for ships by the Marconi Company, a 5KW Rotary Spark transmitter which could be heard over incredibly long distances on the pretty poor receivers extant at that time. Ships then had mostly three letter call signs and I can still remember those two. Bergensfjord was LFB and Alfonso XIII was EDT. Call signs then had some bearing on the ownership of a vessel besides, by the first letter, being identified nationally. The Scandinavian was MNC which indicated her previous White Star ownership. A ‘C’ ending meant a White Star ship, while an ‘A’ ending was usual in the case of the Cunard Line. This became very impractical later on as more and more ships were fitted with radio and changes of ownership anyway made the rule valueless. British ships then had mainly the initial letters of M (Marconi) and G (GPO) and this selected prefix still stands.

Two voyages to Montreal gave me my first taste of a foreign country and I very much enjoyed exploring the place with its queer mixture of English and French. I had a young friend and colleague serving on the Donaldson liner Athenia and we exchanged visits during which many tall tales were told. The Athenia of those days was a four masted ship, somewhat smaller than the Scandinavian and even slower. She was torpedoed soon after with considerable loss of life. My friend was saved but his chief, a fine chap named Gardiner was lost. Her successor had the doubtful privilege of being the first ship to be torpedoed in the Second World War.

A feature of the long passage up the St Lawrence River at that time was the construction of the railway bridge just above Quebec. It is a single span replica of the Forth railway bridge and is, I suppose, still the largest single span cantilever bridge in the world. In my years at sea I was to get very well acquainted with the St. Lawrence River and it never ceased to interest me. The first river pilot was picked up at Father Point, and a brief pause was made to discharge mail at a place called Rimouski, a Russian settlement. Then there was a stop at Grosse Isle on the north side which was the Canadian quarantine station. Pilot changes took place at Quebec and Three Rivers mid way between Quebec and Montreal. An odd circumstance comes to mind which indicates how isolated were the Maritime Provinces from the rest of Canada. There was a chain of Wireless stations between Belle Isle and Cape Race right up river to Montreal. When a radiogram was sent from a ship to Cape Race or Belle Isle destined for Montreal, one could follow its progress right up the river by re-transmission on 600 metres from station to station. Belle Isle would pass it on to Cape Sable who would pass it to Clarke City and so on to Fame Point, Father Point, Grosse Isle, Quebec, Three Rivers and finally Montreal.

A code message could suffer considerably in this welter of potential human error. Back in Liverpool at the end of my second voyage on the Scandinavian I found to my dismay that I was not to be allowed to sail on her again. This sort of treatment was to become all too familiar during my years of service with the Marconi Company. You got to like a ship and then you had to leave her. It had its advantages too because not all ships were happy.

By this time I was getting to know Liverpool very well and I really got to love the place. That could be partly due to the fact that a good deal of the love was for some of its inhabitants! I must say that I had some of the nicest girlfriends ever known in that fascinating city. It was glorious to be young and I have never ceased to be grateful for the friendships so willingly and charmingly vouchsafed to me by the sweet lasses of Liverpool. In spite of the Beatles, the Liverpool Sound and “Z Cars”, Liverpool remains in retrospect my favourite English seaport. I saw my first opera at the Royal Court Theatre, and I never ceased to get great pleasure and fun out of evening excursions to New Brighton on the Famous Wallasey ferries. The Iris and Daffodil stick out in my mind. They were later to be renamed Royal Iris and Royal Daffodil on account of war service. At that time, New Brighton had a tower similar to that at Blackpool and it made a splendid land mark when approaching the port. The tower was built on top of a huge ballroom which was great fun to visit. For some reason the tower was demolished between the wars, and I believe that the ballroom was later destroyed by fire. A sad ending to a nostalgic playground.

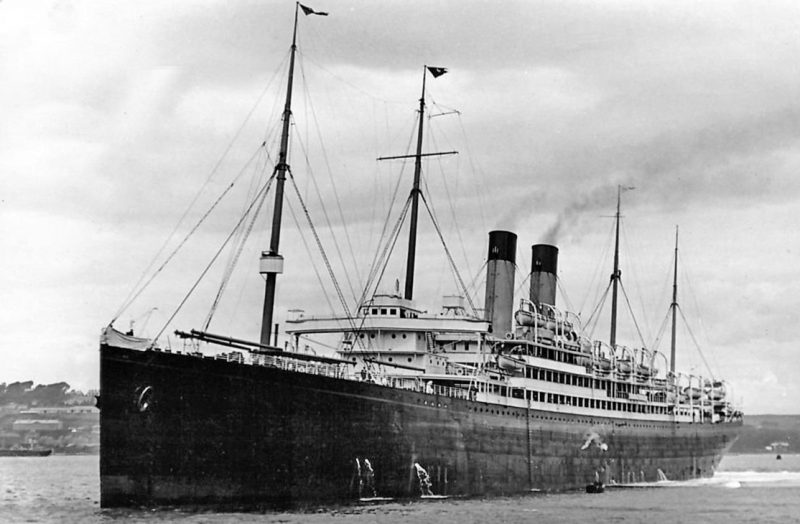

My second ship was the Celtic, and I was greatly chuffed to find that my ships were getting bigger. She was a marvellous ship and nearly twice the size of the Scandinavian. The first and smallest of a group that was known in those days as ‘The Big Four’, she had actually been the largest ship in the world at the time of her launch. About 21,000 gross tons she had two funnels and four masts, the latter not an unusual feature in those days. She also belonged to the great White Star Line which at that time eclipsed all others, including Cunard, on the North Atlantic trade to the U. S.A. and Canada.

The Celtic had just finished a long spell of naval service as an auxiliary cruiser, and as a consequence of this her passenger accommodation had been drastically altered and her fine public rooms denuded of furnishings with parts boarded off. In consequence she was only used as a cargo ship during the single voyage I did on her. Those big White Star liners had vast hold space and the Celtic could carry around 20,000 tons of cargo, which made her an extremely valuable ship for any role. In her wartime service she was mined before I joined her and torpedoed after I left. She survived both of those mishaps and outlasted the war, only to be miserably wrecked off the southwest coast of Ireland in the mid-twenties.

The White Star ships of that era were mostly built in Belfast by Harland and Wolff and were notably beautiful models as well as being tremendously strongly built. A minor feature that I remember vividly was the famous White Star steam fog horn. It had a deep double note of terrific volume and a strange beauty. On leaving Liverpool outward bound there was given a farewell signal of three sets of three long blasts, quite shattering when heard at close range, but also extraordinarily stirring, there was something almost defiant about the sound. My principal recollection about this lovely ship is the small group of navigating officers and my No.1, J. T. Williams of Fishguard in South West Wales. But above all I remember the Captain, Hugh F. David, also a Welshman. He was almost a storybook Captain inasmuch as he was huge, hairy-bearded and awe-inspiring. He was medium in height but very stocky and powerfully built. His hair was jet black with grey flecks and despite being always immaculately dressed in the finest of doeskin uniforms, it seemed as though he never brushed his hair or combed his beard. We were quite convinced that with the addition of a belt stuffed with pistols and a cutlass he would have looked the perfect pirate. He was extremely abrupt and terse in his manner and his staff were in considerable awe of him. He called them all by their surnames and had a habit of addressing everybody as ‘my friend’ in a decidedly unfriendly tone of voice.

However, he was also greatly respected if not exactly loved. I was told that his brother was Bishop of Liverpool and the Captain himself was something of an intellectual. Many years of stormy Atlantic crossings in great ships had left their imprint on that tortured, granite face with its shaggy fringe. He and my boss Williams used to hold long conversations in Welsh and I think they really liked each other.

The only other names I remember were Alcock the Chief Officer and Forster the Senior Second Officer, both in middle age like most senior officers in the White Star. Williams, my immediate boss was also middle aged and one of the nicest chaps I ever sailed with. He treated me more like a son than a rather stupid junior, but had a bad habit of trying to keep tabs on my behaviour in port as well as at sea. He thought I was being extravagant when I wanted to draw ten dollars in New York. I well remember our stay in that port which I was seeing for the first time. We hit the first week of August 1917 and the place was in the throes of the worst heatwave they had had for many years. However, with the temperature in the hundreds and the humidity about the same I still managed to get around the sights to a pretty satisfying degree, I was later to get to know New York much better, but my first impressions of the place were of a city where abundant fun was to be had. Nothing ever tasted nicer than the American ice-cream sundae and my capacity for banana splits was colossal. Then there were the picture shows at Proctors on Broadway, also Loews as well as the delightful funfairs in West 14th St and West 25th St. The picture houses were mostly mixed movie and vaudeville shows.

Pictures interspersed with variety acts and occasional playlets which were never very good. That quarter of New York was not all that pro British although America was just coming into the war. Some of the sketches were of the effete English aristocrat coming into contact with the big hearty frontiersman type of American with much detriment to the former. It was all pretty laughable and the acting was decidedly atrocious. I can’t remember that I was ever unduly upset by the propaganda, after all there weren’t many rugged Frontiersmen around West l4th or West 23rd Streets. When I think about New York in those days, I believe that it was a rather innocent city in comparison to what it has become. The dead hand of prohibition had not taken over and crime and vice were not apparent in any degree. It is probable that there were enough of both but they were not overt as they have become nowadays. The Bowery district of Lower Manhattan had a seedy reputation in those days but there was no need to verify this, and I wandered contentedly around Broadway and Fifth Avenue, the Battery and South Ferry to around 42nd Street and also visited Central Park and Riverside Park. The highest skyscraper at that time was the Woolworth building on Lower Broadway at about 54 stories, but my favourite then and still is the ‘Flatiron’ (about 23 storeys) at the junction of 23rd Street, Broadway and Fifth avenue. It is a wedge-shaped building, built that way to conform to the apex of the ‘X’ created by the acute angle of the intersection of Broadway and Fifth Avenue. Nearly sixty years later I have seen it described as the most beautiful skyscraper in the world. In a way it must have been nearly the first of its kind and it seemed to mark the northernmost boundary of the famous New York skyline in those days. Until the advent of the Empire State Building there were few if any skyscrapers north of the ‘Flatiron’.

Back in Liverpool in late August 1917 I found to my disgust I was not to be allowed to remain on the Celtic and for the next two months I was fated to have my first taste of cargo vessels. However, I was never too hard to please in the matter of ships and soon got to like my new berths quite well.

My first cargo ship was the Romney of the Lamport and Holt Line, a very large Liverpool company with a very mixed fleet of passenger ships, refrigerated meat carriers and cargo boats. Their principal trade was to the River Plate from Liverpool but there were some variations to this. In 1917 of course, the war had upset all schedules and the ships were literally trading all over the place. The Romney was a smallish ship of about 4,000 tons gross and was one of a group of four sisters. Incidentally the name pattern in this company was the use of famous names throughout the ages. The other three of the quartet were the Rossetti, Raphael and Raeburn. The Romney was flush decked fore and aft with beautiful wooden deck planking on the main deck. This always made for comfort because besides being much pleasanter to walk on than bare steel, the wooden decks meant a cooler ship in the tropics. She was a coal burning steamer and was camouflaged in the flamboyant style then practiced. Although I have forgotten some names, I remember my fellow officers very well. First of all my No.1. Aubrey Connock, who is still alive (1970s) after having spent all his life at sea as a Radio Officer. For the last twenty or so he was Chief Radio Officer on the second Mauretania and retired shortly after she was broken up at Inverkeithing, Fife, during the sixties. He was a fine chap and sufficiently near my own age to be good company for me, although I never saw much of him in later life. The Captain was named Pidgeon and rather harmless as Captains go. The Second Mate, Anchers, and the Third Mate, Ben Green, were both splendid chaps and had both served their time in sail on a large four-masted barque called the Owenee.

I have a reason for remembering that ship for I was aboard her many years later when she had been converted into a motor Tanker named Ortina Shell running between Suez and Hurghada for the Anglo Saxon Petroleum Co. (Shell). Ben Green was a great fellow and although only about twenty then he seemed to have the wisdom of a much older man. He talked to me much about the hard life on the old sailing ships, and I have never had any doubt that the life had had nothing but a good effect on him.

The Romney was destined for New York and so, after a fairly uneventful crossing of the western ocean, we loaded general cargo at Brooklyn for Liverpool and also some hundreds of horses and mules which were housed in long wooden stalls in the tween and main decks. My recollection of the return trip in convoy from New York to Liverpool was also without incident, but I have lively memories of the discharge of the mules at the Liverpool landing stage. They were led away in groups of three by troops of possibly the Royal Artillery or ASC, and in no time at all the landing stage was a shambles. One mule alone can be a pretty lethal animal, but several sets of three in a comparatively cramped space, handled by badly trained grooms, represented something which resembled Dante’s Inferno. The chaos was ultimately sorted out, but it made very satisfying viewing while it lasted. This turned out to be my one and only trip on the Romney and I parted from her without any great regret.

CONTINUED NEXT MONTH ….

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item