Neil Thomson Semple, 1917 to 1932

One voyage on the Huronian and onboard the Adriatic

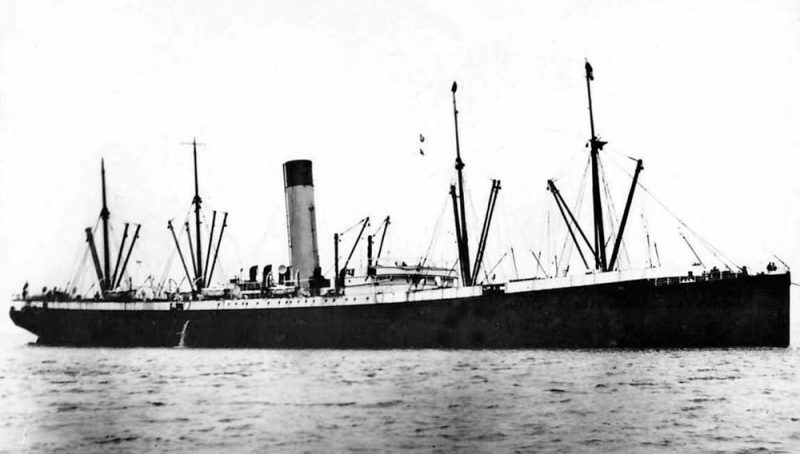

My next ship which I joined about September 1917 was another cargo boat and rather an interesting one in many ways. She was the Huronian of the Leyland Line, an old and famous Atlantic company, which had ties with the White Star Line. It was part of what was known as the International Mercantile Marine group founded some years earlier by the American banker James Pierpont Morgan, which included several British companies, the White Star, Leyland, American, Red Star and Atlantic Transport lines. All of those except the American Line flew the Red Ensign but were largely owned in New York. Although Morgan had a controlling financial interest in those companies, the British Government would not allow the manning and running of them to be transferred. During the twenties this combine more or less fell apart when the White Star was absorbed by the Cunard Line.

The Huronian was a big ship with four masts, quite a common rig for both passenger and cargo ships in those days. She was also a well found and well fed ship with a comfortable wireless room situated at the after end of the boat deck. The radio equipment was of the usual type for that era, a 1.5 kw rotary spark transmitter with a magnetic detector. An emergency transmitter was also provided which consisted of a 10-inch induction coil which ran off high capacity batteries giving 24 volts.

The Huronian left Liverpool around the end of Sept 1917 for the usual unknown destination via a convoy port which in this case turned out to be Lamlash in Arran. I had the extremely odd and exhilarating experience of opening the wireless room door at about 6am the next day to find our ship steaming up the Kilbrannan Sound. It was a fine day and there was High Ugadale, my home and birthplace just about two miles away on the port side. I imagined I could see my father and brothers working in the byres and stable while my mother would be getting the breakfast ready, but I could only sit there on the high door coaming and look and yearn, till we were far past lovely Saddell Bay. Finally we crossed over to round the north of Arran, past Lochranza and Corrie, and thence down past Brodick with its fine view of Goat Fell to Lamlash. The reason for this unusual use of Kilbrannan Sound by a big ship was some kind of submarine scare. Vessels in and out of the Clyde pass to the east of Arran practically all the time for the simple reason that it is the shortest route. Normally only the river steamers use Kilbrannan Sound, although there is plenty of good deep water there. It remains very vividly in my mind that the Grand Fleet held exercises in the Kilbrannan Sound around l910 and actually did gunnery practice for some weeks just off my home. We had a ringside seat so to speak of such battle wagons as the Iron Duke and Collingwood trying out their 17 inch main armament.

Our outward passage in convoy was fairly uneventful and we found ourselves bound for New Orleans which made an exciting change for me. This French city in the midst of the United States was going to provide me with new experiences, but sadly I remember very little about it. The city itself was approached from the riverside quay on the Mississippi by the bumpiest tramcar on the bumpiest dock road I have ever travelled. Strangely enough I remember the name of that street, Tchoupi-Toulas, (an Indian name) and then the fine main street itself, Canal Street, with its formidable array of department stores.

We returned to the UK by way of New York where we picked up a convoy and arrived back in the Mersey without mishap in mid-November 1917. Up to now I had led a charmed life and although I had now spent the first six months of my sea career largely in the danger zone during the worst period of the U-boat offensive, I had seen very little. Scares there had been of course, but I had not seen a torpedo fired in anger. Even the convoys my ships had been attached to had all come through unscathed, at least while I was around, and I honestly do not remember ever having given much serious thought to the subject.

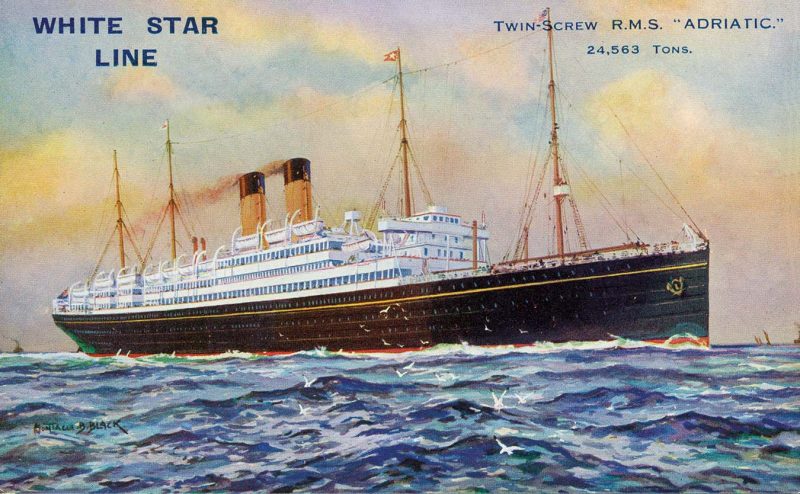

The last year of the war found me on my greatest ship ever, the famous old White Star liner Adriatic. She was a beautiful ship and I loved every sleek line of her. The biggest of the ‘big four’ lovely sisters, Adriatic, Baltic, Cedric and Celtic in that order. She was 24,563 tons gross with two funnels and four masts and was over 700 feet long, and for a brief period after her building in 1907 she was the biggest ship in the world.

As I have already indicated, those big White Star liners were probably the most valuable ships in the Merchant Service at that time. Not only could they carry passengers or troops as required but they could also carry tremendous cargoes. The Adriatic was used for those purposes throughout the war, came through unscathed, and was fortunate enough never to get taken over by the dead hand of the Admiralty during the war. Unlike the Celtic she was saved the stint of being an auxiliary cruiser, and although she carried very many troops, she carried them as passengers and her accommodation was not interfered with in any way. Troops were catered for as passengers, officers 1st Class, NCOs 2nd Class and other ranks 3rd Class.

Large numbers of civilian passengers were also carried in the usual way and during 1918 I was privileged to meet or rub shoulders with many great names. It must be understood that the Wireless Operator in those days was not taken very seriously by his shipmates. He had been granted very grudgingly ‘officer status’ by the various shipping companies and a very odd privilege accrued in that the Marconi Company managed to arrange that we should dine in the lst Class saloon along with the passengers. This gave us an enormous advantage over all other departments because, in the main, only the most senior officers such as the Captain of course, the Doctor, the Purser, the Chief Officer and the Chief Engineer were allowed this privilege.

Among the many famous names I remember among the passengers we carried on the Adriatic, a few stand out. Captain Amunsden who beat Scott to the South Pole travelled from New York to Liverpool early in 1918. He was a big, fine looking man with a mass of white hair, very blue eyes and a formidable hooked nose. His ear-lobes were a deep blue and I remember thinking that those were probably frozen stiff for long periods in his life. The famous Sir F. E. Smith went with us to New York and made an after dinner speech one night extolling the role of the merchant seaman in war. He said that he had spoken to members of the crew who had been torpedoed as many as three or four times. He was a tall, rather thin man who became even more famous later as Lord Birkenhead and who was undoubtedly an outstanding barrister and Liberal Minister. My greatest favourites were a dear old couple retiring from Foreign Service in the Empire. Sir Bickham Scott had been Governor of Fiji and with Lady Scott was on his way to retirement at home. They were a most gracious and charming couple and they developed a rather embarrassing liking for my company. When I arrived in the saloon for breakfast each morning they insisted that I join them at their table and tell them all the war news I had received on our marvellous wireless set during the night. I got the impression that they both liked me very much, and I have often wondered whatever they saw in me, for I was pretty callow in those days and had not altogether lost the ‘reek’ of my highland home. Dressed in a pretty cheap reefer uniform, with unruly hair and not too clean finger nails I must have presented a very odd spectacle indeed. I never saw them again of course, but retain a very warm feeling for both of these wonderful and kindly people. I should think they were the best sort of colonial administrators, who were the backbone of the empire.

At this point I must introduce an American navy Signals Officer who was returning to his base at Arlington, Virginia, from a mission to Europe. He was a radio expert and spent all his spare time in the wireless room where he kept my senior and I very much enthralled with his stories about the marvellous equipment he worked with at the big wireless station at Arlington. At that time one of our jobs was to receive and publish on board news bulletins which were sent out daily from Poldhu in Cornwall and Arlington in the U. S. With the rather primitive receivers fitted on ships in those days, it was only possible to receive from Poldhu up to a point about mid-Atlantic and thereafter the bulletins from Arlington took over. Our American friend told us of a new thing that had been introduced into the receivers at Arlington called the ‘de Forrest audion’ and it was in fact the first three-electrode valve. We listened open-mouthed while he told us of standing in the great hall at Arlington and reading Poldhu’s signals with the phones lying on the table! To us, used to agonising over trying to read almost inaudible signals through persistent static interference, this sounded like some kind of paradise. The outcome was that he presented my senior, Mr Thomas Murray, with an authorisation to purchase an audion from the Brooklyn Navy Yard when the ship reached New York. Murray and I both went, carrying with us all the money we could dig up, about ten dollars, and on arrival at the dockyard we were escorted from office to office by two stalwart marines carrying rifles with fixed bayonets. We finally emerged with the audion which cost us 5 dollars. I regret to say that during our experiments and attempts to get the thing to work, we accidentally got the 24 volt supply onto the filament of the valve, and that was that, bang went 5 dollars!

My senior, Thomas William Alfred Dixon Murray, to give him his full name which for some reason I have never forgotten, was about ten years older than me, and he was one of the elite band of great telegraphists whom the early Marconi Company recruited from the Post Office, the cable companies and the railways. Their one qualification was that they were telegraphists ‘par excellence’ and as such they more than justified themselves, and remained the nucleus and backbone of the radio service on British passengers ships for the first thirty years of the century, Although some were not academically well qualified, they could send and receive at incredible speeds under the most trying conditions. It would be no lie to say that they made the Marconi Company viable, for the receipts from passenger radiotelegraph traffic during that period (except for the war years) were enormous, half going to the shipping company and half to the Marconi Company. The arrangement then was that the radio installation and the telegraphist were hired out to the shipping company for a yearly sum of money that covered the maintenance of the equipment and the salary of the telegraphist. That annual amount was so embarrassingly small that it was well covered by the takings of one crossing of the Atlantic by the average passenger ship. This arrangement lasted almost up until the Second World War, when at last realism overtook events.

The job in some ways was a fascinating one, and in spite of low wages men remained loyal. Our leave periods were almost non-existent, our foreign service conditions were so very had that we were known on the Indian coast as the lowest paid Europeans in the East. Our sick leave treatment was iniquitous as regards pay, half pay for two weeks and then off pay altogether thereafter, and that also applied to Foreign Service. The final indignity was the fact that although the radio officer signed the same articles as everyone else on the ship, he was not entitled to repatriation by the shipping company if the normal two-year agreement ended in a foreign port. There was also the pretty beastly business of being transferred from a home trading ship to a foreign service ship while abroad. This mainly applied to Indian, Straits Settlements ports and also Hong Kong. This practice was written into our agreements and into the agreements between the Marconi Co. and the shipowners. The whole scheme was diabolical in its cleverness inasmuch as it never involved the need for men to be sent specially to those ports in order to man foreign service ships, and it also saved the expense of sending him home again at the end of his tour of duty. He simply transferred to a homeward bound ship. The simplicity of this was obvious to all but it does nothing to bring out the heartbreak that was often involved. A man attached to a home trading ship who has perhaps some compelling reason for getting home as soon possible suddenly finds himself transferred willy-nilly to a ship that never goes home and there he is, stuck for perhaps another two years. And through it all we remained loyal and I stayed with the Marconi Company for fifty years.

To revert to the Adriatic and Tommy Murray, I did in all, five voyages on her between December 1917 and July 1918 during which I saw much North Atlantic convoy work and also trooping in a big way. I was able to renew my acquaintance with New York and wasted no time on board while we had usually a week’s stay each trip.

The other officers on the Adriatic were the usual middle-aged to elderly types found on the big liners of those days. The Captain was a solidly built bearded embodiment of authority. His name was Ransom and he was well liked from what I remember. Strangely I do not remember the name of any other deck officer, but I do remember the Chief Engineer, a very large white moustachioed Clydeside Scotsman named Jimmy Reid. He had a staff of around twenty five engineers under him and he was a bit of a martinet. I had made friends with the second Electrician, a small active Lancastrian, and one day I was helping him to do a soldering job on a small fan motor, and we had a blow lamp going just outside his cabin. Unfortunately, old Jimmy came along and did his nut. Gave my friend Sammy a good old-fashioned bollocking for using a naked flame near an open hatch and then he told me with much profanity to get back to my own bloody end of the ship. I can still see that scene in my mind’s eye because of the environment. Engineers in those big ships lived in what was known as the working alleyway, probably the lowest inhabited deck on the ship, and a pretty grim place it was too.

The junior engineers in those great ships were pretty hard working lads and each watch required two of them to be in the stoke holes throughout, where they were glorified slave drivers. They had to see that the furnaces were maintained at their highest possible efficiency and that meant driving firemen and trimmers to the limits of their endurance at times. The Adriatic burned about 500 tons of coal a day which meant the shovelling of 50 tons each watch. This is not as simple as it might sound because it had also to be transported by shovel and barrow from the bunkers to the stokehold by the trimmers. Then it had to be shovelled into the furnaces by the firemen. Maintaining a good fire was an art in itself which had been brought to a pitch of perfection by the tough Liverpool firemen. Dead ashes had to be withdrawn, the fire itself stirred up by the use of a long slice and the fresh coal distributed to best advantage onto the fire. All this had to be done without disturbing the maintenance of a proper head of steam. Cleaning fires at the close of watch was a tricky business and a badly organised stokehold meant some loss of speed during that operation. Then woe-betide the junior engineer who failed to keep his end up.

Leaving New York one voyage we had a ring-side seat and view of a most remarkable and tragic accident. We had just pulled out into the Hudson from the White Star Pier 60 when the American Line liner St. Paul was being warped into a berth lower down, I think about Pier 56. She had been in dry-dock at Brooklyn for overhaul and was flying light. Whatever happened, she took a small list to port when she was almost alongside, and then she started to go over very quickly. Before we had straightened out and got underway on our passage downstream, the St Paul was lying completely on her side. She was a ship of 11,629 tons gross with two funnels and three masts, a not unusual rig at that time, and we heard later that she had taken water through openings on her port side near the water line which had been negligently allowed to remain open following her overhaul in dry-dock.

During my first voyage on the Adriatic we left New York for Liverpool about the end of l9l7, and proceeded to Halifax, Nova Scotia where we were to pick up our convoy for the trip home. Halifax, on account of its magnificent harbour, was probably the principal convoy assembly port in the two wars and I was destined to get to know it very well. But this particular voyage of mine was to have special significance because when we arrived in the Canadian port early in January 1918 we found that the town had been partially destroyed about four weeks earlier by one of the greatest explosions on record (before the advent of the atom bomb).

Halifax has two harbours connected by a two-mile long channel leading from the main outer harbour to the inner one known as the Bedford Basin. Two ships had collided in the passage, one of them unfortunately carrying about 5000 tons of T.N.T., probably the heftiest explosive at that time and she was set on fire. The crew very wisely headed for the hills screaming for everybody to take cover, but the penny did not drop and a naval fire-fighting team was actually boarding her when she went up. The damage done to Halifax was devastating and the loss of life in the town and harbour tremendous, but the catastrophe was compounded by the fact that a blizzard ensued and vary many people died of exposure.

Our convoy main escort vessel was usually the converted White Star liner sailing as HMS Teutonic. She was an older ship than the Adriatic and was rigged with two funnels and three masts. On one occasion we had the real cruiser, HMS Devonshire, for escort, a three funnelled light cruiser with eight six-inch guns. That was the usual armament of the auxiliary cruisers requisitioned by the navy from the merchant service, but all similarity ended there. The latter were difficult to ‘fight’ on account of the positioning of the guns, while the high freeboard and top hamper of converted passenger ships made them very easy and vulnerable targets. They fared rather better than they deserved during the first war and one of them, the Cunard liner Carmania actually fought and sank a similar ship, the converted German liner Cap Trafalgar. But their record in the second war was abysmal, where they were destroyed by the German navy with monotonous regularity.

Fast cargo boats were the only answer if such ships were really necessary, and the German record in this context during the second war proves my point. Their fast cargo ship raiders fought and beat every British auxiliary cruiser they met and one of them, the Kormoran, actually destroyed the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney.

During the months that followed in 1918, we ran mostly in fast troopship convoys, sometimes of only about six ships, and the Adriatic was sometimes ‘Commodore’ ship which meant carrying a naval Commodore, usually a retired Admiral, and his staff of signallers. The duties of the Commodore ships were to act as a kind of working boss of the convoy under the benevolent eye of the naval escort. The record of these fast troop ship convoys during 1917 and l9l8 was pretty good and I only know of one of them being lost by enemy action. This was the Anchor liner Tuscania which was torpedoed off the West Coast of Scotland early in l9l8, after she had left the convoy. It was the custom for those big ships to be dispersed before the actual crossing was completed in order that they might carry on to their ports of destination at full speed. We did not hear about the Tuscania until long after, or it might have shaken some of us out of our complacency.

But we had our shocks to come and I well remember a bright spring afternoon when we were outward bound in a fairly large convoy when quite suddenly all hell broke loose. We were all zig-zagging at moderate speed round the north coast of Ireland and were actually in the narrow passage between Antrim and Rathlin Island (only a very few miles from my home in Saddell), when the small P.S.N.Co. passenger ship Orissa was torpedoed just ahead of us and about a quarter of a mile away. She took about twenty five minutes to sink and as I watched her going slowly by the stern I was glad to see that they seemed to be managing the boat launching not too badly. Then there was another heavy explosion and the Elders and Fyffes liner Tortuguero on the other side of us disappeared before my very eyes. I estimated she took about two minutes to go and I was pretty sure there could have been few survivors. Bridge messengers were running to-and-fro between the wireless room and bridge for the next hour and altogether we collected about six distress calls that afternoon from our own convoy. By this time the escort had instructed the convoy to disperse at full speed and the relatively slow Adriatic was worked up to about twenty knots, actually overhauling the Cunard liner Caronia which I had always supposed to be a much faster ship.

Nothing more happened fortunately and we reached New York safely a few days later.

The Adriatic was my greatest ship and she survived the war with her three sisters and continued on her trans-Atlantic career well into the thirties, being finally broken up in Japan in 1955. I remained on her until the end of July 1918 without further incident, having created some sort of record by managing to hang on to her for five voyages.

CONTINUED NEXT MONTH ….

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item