The unique funnel-less ships of The Danish East Asiatic Company

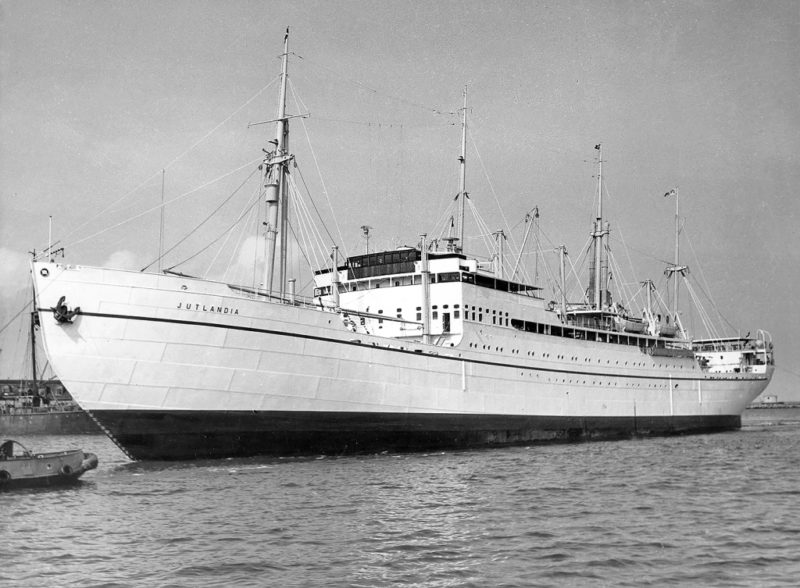

In 1961 I was serving as a young midshipman on board the Glen Line of London’s good ship Glenshiel. On a sweltering afternoon whilst on cargo watch at the crowded anchorage of Port Swettenham (now Port Klang) in Malaysia, I chanced to look over the starboard side of the fore deck just as a large outbound ship ghosted by at slow speed. She was the 1934 built Jutlandia, belonging to the Danish East Asiatic Company, and I never forgot how graceful and completely unique she looked, even compared to the good looking ships of The Glen and Blue Funnel Lines of Great Britain. I later that day understood her to be just one of a class of ships reaching back to the early parts of the twentieth century, and that she was probably the very best of them.

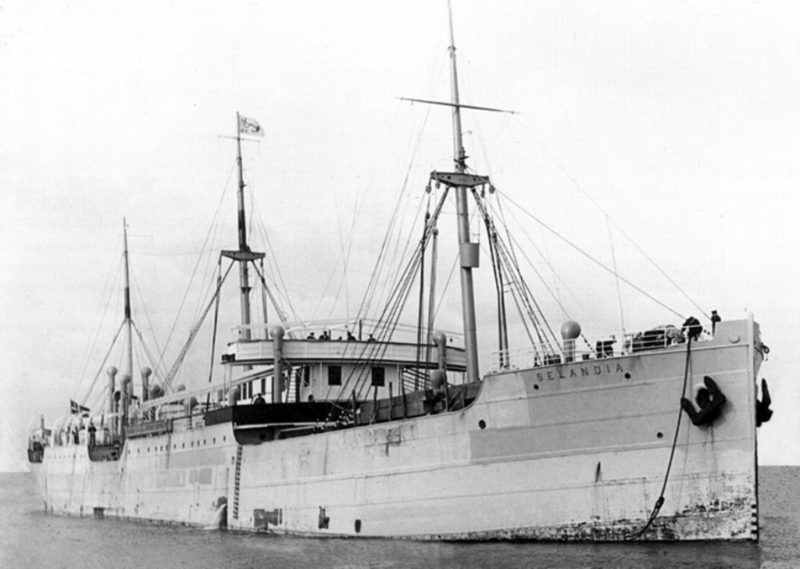

The Selandia of 1912 and the Jutlandia of 1934 largely ‘book-ended’ a period when the Danish East Asiatic Company was very much a key player on the European to Far Eastern maritime trade routes. The Selandia was not the first ‘funnel-less’ EAC ship, just as Jutlandia was not the last, but for entirely different reasons they both became very famous indeed.

When the idea of the motor ship ‘Selandia’ was first conceived in 1911, it was clear that what was truly ground-breaking was not the lack of funnels, but rather the method of propulsion. Despite that, the sight of successive funnel-less ships under the EAC flag as the twentieth century wore on never ceased to arouse curiosity, dislike or admiration in equal measures, wherever they were seen. From the ground-breaking innovation of the motor ship Selandia in 1912, to the demise of the much admired Jutlandia in 1965, they were uniquely unmistakeable.

In maritime terms, the arrival of the diesel engine in 1894 as designed by the German inventor Rudolph Diesel caused little stir initially, since early models were too small with too low an output to be considered for installation on-board large ocean going vessels. But when Burmeister & Wain acquired the Danish patents in 1901, they embarked on a programme of research and development which culminated in the production in 1911 of an engine capable of powering a ship the size of the proposed new building for EAC, namely the Selandia.

The Selandia thus entered service in 1912, with a deadweight of around 6,800 tons, a length of 370 feet and breadth of 53 feet, arguably the first ocean going diesel powered vessel, although the Dutch motor tanker Vulcanius also lays claim to that honour. She featured a twin screw system, and her B&W engines were two 8 cylinder 4 stroke units. Very soon, the advantages of this method of propulsion at sea became clear to ship owners, due to the huge savings to be made in fuel costs, the reduction in the weight of diesel fuel as compared to coal, the subsequent increase in cargo and passenger capacity, and reduction in crewing costs. No more armies of stokers to tend furnaces and boilers!

From the standpoint of the ever increasing awareness of the threat from global pollution levels in today’s world, in 1912 the Danish East Asiatic Company could have pointed proudly to the fact that at a stroke, marine pollution levels were reduced by 50% whenever a coal powered vessel was replaced by a diesel powered one. How times have changed.

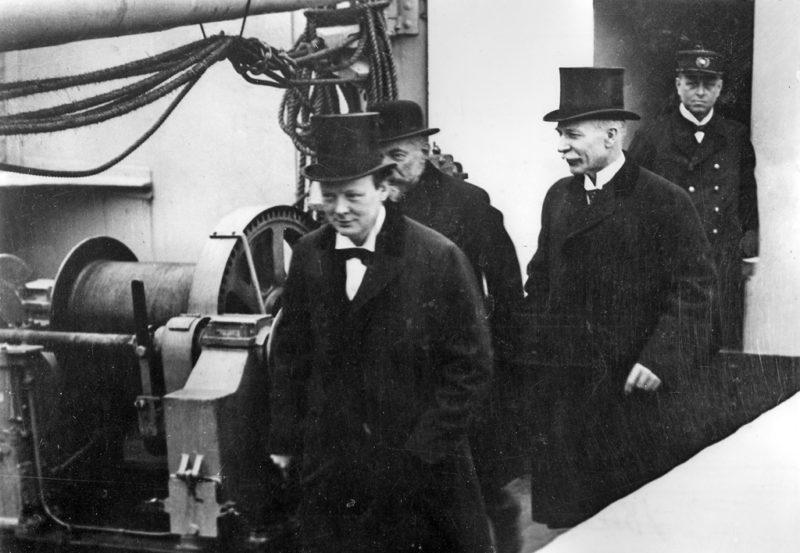

On her maiden voyage, when she first visited the Port of London, Winston Churchill himself, in his capacity as First Lord of the Admiralty and accompanied by senior naval staff visited the vessel, clearly aware of the implications for the future of Great Britain’s primacy at sea.

After that Port of London visit, the Selandia’s maiden voyage continued in earnest, with outward bound calls at Antwerp and Genoa, through the Suez Canal and eastwards toward Colombo, Penang, Singapore and ultimately Bangkok. The homeward bound voyage followed a similar pattern, and despite some teething issues, the new propulsion system undisputedly proved its worth. On completion of the voyage, Selandia was joined by the second vessel in the class, the motor ship Fionia, which was almost immediately sold on at a premium and reflagged to Germany, to Albert Ballin of HAPAG fame.

EAC continued to drive the diesel project on, and agreement was also reached to continue the rapid fleet expansion by allowing British shipyards and others to share and develop the new engine technology, the first of which was the Barclay Curle yard on Clyde side. This third diesel powered vessel was the first to carry the name of Jutlandia, and she marked the beginning of a long relationship between EAC and Clyde shipyards, despite a rather inauspicious start.

When Jutlandia departed on trials prior to handover to the East Asiatic Company the main engines promptly seized up after only a few revolutions. Fortunately tugs were still attending, and so she was quickly re-moored whilst investigations were carried out. Burmeister & Wain engineers were brought over from the continent, and before too long it was established that different interlinking components had been manufactured not only on Clydeside but also on the continent. Great Britain was using the imperial standard of foot and inches for machine parts, whereas Burmeister Wain used metric measurements. A serious degree of intolerance had been introduced, which took some time to successfully resolve.

The Selandia boasted excellent first class passenger accommodation for up to 40 persons, however, no one would ever claim that this initial class of motor ships were graceful in appearance. Many associated the grand statement of a large, strikingly coloured funnel as being essential in maintaining the status of a liner company, without ever consiering the possibility of other alternatives. For passengers, the advantage lay in the avoidance of dense clouds of black smoke and the occasional dollop of hot soot falling upon the passenger decks were the wind to be in the wrong direction, a condition normally associated with many of the coal burning steam ships common at that time. But it was clear her grey painted hull, white superstructure and yellow masts did not seem to meet with much approval from the general public.

In addition, with the practise of leading exhaust gases clear of accommodation towards a mast, passengers were spared from experiencing noxious diesel fumes and even some associated engine noise.

This Selandia continued in service with EAC until 1937, then was briefly Norwegian owned under the name Norseman, before being transferred to the Panamanian register. 1940 saw ownership again transferred to the Finnish register, and now named Tornator she finally found herself part of the Japanese war effort when caught in Yokohama as Japan entered the war. She eventually ran aground and broke in two during a voyage in support of the Japanese, an inglorious end indeed for such a historically important ship. Nevertheless, in February of 2012 and on the 100th anniversary of her launch, her importance in the development and expansion of the global maritime world was widely recognised, especially by the Mann Corporation who are now the custodians of the Burmeister & Wain legacy.

The Danish East Asiatic Company generally persevered with the funnel-less concept for over two decades, building and refining the concept, until finally in 1934, they produced a truly graceful and funnel-less ship. She was the third ship to bear the name Jutlandia, and went on to enjoy not only commercial success, but also a worldwide reputation for giving much humanitarian aid in the most difficult of circumstances. In addition to this, she also enjoyed a period of being the Royal Yacht for two separate countries, circumstances quite unimaginable for the normal range of cargo/passenger ships of the twentieth century.

Curiously in the 1930s, the final three funnel-less ships built included both a Selandia and a Jutlandia, the third and final ship being the Falstria. They were both in fact the third generation to bear their respective names which live on in post war built tonnage, currently as Ro-Ro freight carriers with DFDS.

The differences in appearance between the 1934 built Jutlandia and the 1912 built Selandia were plain to see. Gone was the angular and bluff bowed outline of the first built ship, to be replaced by a much more graceful hull form altogether. From her Maier-form bow, which in many ways gave the appearance of an icebreaking capacity, to her gracefully proportioned deck accommodation and gently raked masts, this final funnel-less version truly did seem to have more in common with the most graceful ships of the clipper age of sail. The fact that she had four raked masts instead of the three on board the early Selandia also lent her a more balanced appearance, and the Asian crews employed aboard her affectionately described her profile thus – “four stick bamboo, no puff puff”.

From the very beginning this Jutlandia led a very different life to her predecessors.

Built at the famous Nakskov shipyard in Denmark, her early years were spent on the company’s traditional European to the Far East route network, however in 1940, whilst undergoing overhaul and refit at the Nakskov yard, Germany attacked Denmark. The result of this was that the Jutlandia and two other EAC vessels were laid up at Slote Island and placed beyond action for the remainder of the war, although curiously the three ships at one point came under attack by the Royal Air Force, who feared their return to duty in aid of German forces. Jutlandia suffered only minor damage, however the other two ships came off much worse.

On the conclusion of hostilities in 1945, Jutlandia was returned to duty with the Danish East Asiatic Company, and for a time was employed in her cargo and passenger carrying role. However in 1950 she yet again became caught up in a conflict. The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 and the involvement of the United Nations saw the Danish Government fulfilling its part of the UN Mandate by supplying the forces of the United Nations with a hospital-ship which would look after the inevitably wounded and injured soldiers from all the different nations fighting on behalf of South Korea and the U.N. itself. After a lengthy refit she set sail from Copenhagen ready to treat up to 356 bed-bound casualties. Her normal ship’s complement was swollen with the addition of 91 doctors, specialists and nurses, and she went on to serve outstandingly in her role for a total of 999 days during three separate tours of duty.

During the Korean conflict she sailed under the flags of Denmark, The United Nations and the International Red Cross Association, and even to this day she is fondly remembered by the people of South Korea and Denmark in addition to the many injured soldiers and marines who received such excellent care onboard. The people of South Korea especially remember the help given by the crew of Jutlandia to the many young children who also suffered so badly at that time.

At the end of the conflict, Jutlandia was converted back in order to resume her role as a cargo/passenger ship, but in 1960 the East Asiatic Company placed her at the disposal of the King of Thailand. Her role was to act as a Royal Yacht for a State visit to Denmark, Norway and Sweden, and so it came to pass that Jutlandia, in her final years, was thought grand enough to host Kings and Queens, and to hold state dinners on board in Copenhagen for the Kings and Queens of Denmark and Thailand. This operation proved so successful that when in 1963 the Crown Princess, later Queen Margrethe of Denmark was sent on a State visit to Thailand, it was decided to again commission Jutlandia as a Royal Yacht, this time for the Danish Royal family.

This Royal commission was again successful, but by 1964 Jutlandia had been returned to her normal duties for the final time. Change was coming to maritime trade, passenger numbers had reduced to near zero because of the growth in air travel, and EAC decided that there was no place for Jutlandia in the future development of their operations. In 1965 she was unceremoniously consigned to a ship breaking yard in Northern Spain, and that should have been the end of her story, but, not so! Over twenty years later the Danish musician Kim Larsen released a song called ‘Hey Ho Jutlandia’, which became an enormous hit, and rekindled an interest in this long departed ship. Now she is remembered and respected by the people of South Korea who installed an inscribed stone memorial to the ship and her crew on the Langlinie promenade in Copenhagen, not far from where she first set off on her humanitarian voyage on behalf of the United Nations and the International Red Cross. Meanwhile, a small band of committed former crew members, all now into advanced old age, still keep Jutlandia’s remarkable and varied story alive in Denmark.

The Selandia of 1912 and the Jutlandia of 1934 have very clearly earned their place in maritime history in Denmark and indeed the wider world.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item