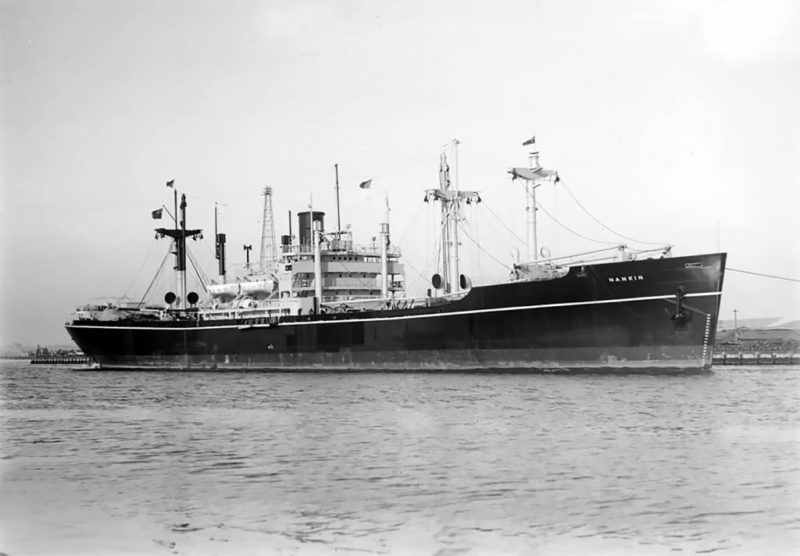

In February 1957 at Brisbane, Australia, Nankin had finished loading a general cargo of wool and mineral sands for Japanese ports. Also included were several tons of steel sheets for Shanghai, these were for discharge at the Port of Shanghai. Nankin would visit the port after Japan and would be the first Eastern & Australian SS Co. ship to do so after the port had been opened by the Communist authorities after the escape of HMS Amethyst some 8 years earlier.

Loading completed, Nankin was waiting for the carpentering contractor to finish building the cattle pens on her fore and after decks. The cattle, Zebu’s, were already alongside in trucks and the two cattlemen who would look after them during the voyage to Japan were already at work installing feed and water bins.

Nankin headed out into the Coral Sea on a direct course to Nagoya, ,Japan to unload the cattle before calling at other ports to discharge the wool and general cargo.

The weather reports for the Coral Sea included a possible low forming in the area that Nankin would transit. As she entered this area the low was identified as a category one cyclone. The wind increased, the waves became higher and the ship started to labour, taking green water over the bow. The cows packed into their stalls were unsettled at the start of the voyage. With the change to their environment, they were now obviously terrified with the severe motion of the ship and the seawater swirling around in their stalls. What the waves breaking over the bow didn’t damage on the stalls their frightened lunging did the rest.

All the fore deck stalls were in ruins, their occupants were loose on the main deck. The cattlemen charged with their care were powerless to do anything with their charges until the weather moderated to allow the ships motion to stabilise.

With the cows virtually having the run of the ship the first of the several mishaps occurred. The Chief Engineer’s cabin became a place of interest for one steer who demolished the cabin while he was being removed. It took a lot of cleaning to make the cabin habitable again. The second was when another steer’s curiosity with the activity in the Chinese Bonus’s cabin managed to get its head stuck fast and had to be euthanised.

The weather moderated as Nankin sailed further north. On the first fine day work started to repair as many stalls as possible with what timber was onboard, and dispose of the cows that had either died of fright, or had to be euthanised because of the injuries suffered during the worst of the weather.

Closer to the port of discharge Nagoya the cattle men reported to the Chief Officer that they were out of cattle feed due to some having been washed overboard during the tempest.

After an exchange of wireless messages the Japanese authorities acted swiftly and arranged for the ship to discharge the cattle at Nagoya and undertake quarantine and customs inspections at her next port of discharge, Yokkaichi, which was across the bay from Nagoya.

After completing the discharge of her Japanese cargo and some loading for the Australian ports, Nankin’s last port in Japan was Moji to pick up a cargo of bagged cement for Shanghai. This to be loaded out of three lighters tied up alongside. All very straightforward, until the proposed sailing time for Shanghai had passed with the empty lighters still alongside. The Harbour Pilot, already onboard, seemed unfazed as if this was a regular occurrence in Moji. Some five hours after sailing time a tug arrived to remove the lighters, one at a time. The Master Captain O’Neill was worried that his ship would be very late for quarantine and customs inspections at Shanghai and how this would be received by the Port authorities.

As it turned out he had every reason to be concerned even after the Chinese had been advised several times by radio about the unavoidable delay to the ship at her last port.

Nankin entered the Yangtze River and headed toward Woosung Ports pilot station joining several other ships undergoing medical and military inspections. The Chinese seemed to ignore the ship at first until contact was made by signal lamp requesting name and signal letters and port of registry.

The next contact was with a military patrol craft with P.L.A. soldiers onboard. Their Officer bounded up the gangway and in reasonable English demanded to see the Captain. The P.L.A. soldiers meanwhile had started a search of the ship.

The P.L.A. Officer had rounded on the Captain and in a high pitched voice accused him of insulting the Chinese People by being late. The wireless messages advising of the late arrival were offered, but the Officer would have none of it and continued to harangue those on the bridge on politics Chinese style only stopping with the arrival of the River Pilot.

The all consuming inspection included locking up the radio room, all charts, all English publications wherever they were found, Azimuth mirrors after the gyros were shutdown, personal radios and record players and records, navigation books including the apprentices study books were llocked away. The radio room was then sealed with rice paper seals.

Four of the P.L.A. soldiers were to remain onboard the ship for the duration of its stay in Shanghai, their food and accommodation would be provided by the shipping company.

Inspection of both material and quarantine completed, Nankin was given permission to proceed up river to her berth at Shanghai under the direction of the River Pilot, who spoke very little English and even less Cantonese much to the chagrin of the Cantonese Quartermasters.

The month of April was early Spring in central China, with persistent thick weather and very cold when the sun set. The Forecastle crew had all donned their parkas ready for the two hour standby to the berth.

The area around the Woosung establishment was flat with paddy fields and very little of interest until a military base and airfield was visible to starboard. The runway ended at the river’s edge. Jet fighters taking off shook the ship with their jet blasts, to the enthusiastic approval of the pilot.

After the military base the river straightened out with even more river traffic to contend with. In the distance just visible in thick weather was a large oceangoing Junk. The sighting reported to the Pilot received a grunt and a shrug of his shoulders as acknowledgement. He seemed more interested in the food he had in front of him. Further reports about the Junk from the Third Officer on the forecastle received even less acknowledgement. At about 200 metres distance Captain O’Neill took control and rang Stop on the telegraphs. The Pilot suddenly sprang into action, screamed some Chinese abuse aimed at the Captain, grabbed the telegraph handle and rang Full Ahead once more.

While all the fracas on the bridge was going on, Nankin had used up all the margin of safety she had. Those on the ship in visual range watched transfixed in trepidation and then horror, as the ship hit the Junk amidships, cutting it in half. The forecastle crew ducked for cover as they were showered with pieces of wreckage. The two halves of the Junk slid down each side of the ship. Those port side saw the occupants whose home and livelihood the ship had destroyed shake their fists in anguish as they were swept into the area around the propeller which with Nankin being a nearly light ship, was exposed.

Those on the bridge were thunderstruck, not so the Pilot who continued to behave as if nothing had happened. He eventually explained to all who would listen that to stop engines would have caused the ship to hit the riverbank and block the waterway and be in more trouble than she was in already. From later reports some of the Junk crew had lost their lives, the number of victims varied depending on which of the P.L.A. were telling the story.

In an atmosphere of disbelief the stand by continued. The misty afternoon became a black night with frequent light rain showers. Closer to Shanghai the river traffic became thicker, some of the sampans had lanterns however they were a minority, the other craft were mostly unlit. The forecastle crew were on edge after the collision and the bridge phone rang with every sighting. Shanghai suddenly appeared out of the misty rain as small cluster of lights along the riverbank. Nankin’s berth on ‘The Bund’ required her to berth port side to the wharf. The Pilot not used to a ship with Nankin’s engine power completely under estimated the distance needed to swing in a limited space hit the wharf with a shattering crash tearing off the wharf stringer which fell into the river. The Pilot at last showed some contrition he seemed more concerned about the damage to the wharf than the loss of some of the junks occupants.

The witnesses to the collision with the Junk gave signed statements that were entered into the ships log.

All of Nankin’s Officers were expected to undertake a tour of the Chinese Peoples Friendship Building built by Russia as part of their education about New China and the Government.

After two days cargo work Nankin was ready to depart, but her request to do so was refused by the Chinese Authorities. The reason for this was a diplomatic stand-off between Hong Kong and Beijing over a P.L.A. journalist’s printed comments about the British Administration. He was given house arrest in Hong Kong. Nankin was now under arrest in Shanghai. Being of British registry, it suited the P.L.A. Administration to bring pressure on Hong Kong to release their journalist.

Nankin was towed out into the middle of the Whampoa shackled fore and aft to two buoys and left with the only contact to the authorities, the four armed guards still onboard.

The Captain, wisely as it turned out, decided to impose rationing on fuel, water and food because there was no indication of how long they would be detained. Without books, newspapers or radio news there was nothing to do and all day to do it in, except watch continuous red guards demonstrations on The Bund and listen to the loudspeaker in the streets that ran 24/7.

Days turned into weeks and the Captain’s worst fears were about to be realised with the rationed supplies running dangerously low. Also with the Summer heat approaching Nankin without any forced draught would be difficult to live in, adding to a now dispirited crew. The diplomatic wrangling eventually produced a result favourable to the P.L.A. and the journalist was taken to the border checkpoint in the new territories in Hong Kong and handed over.

Nankin’s release from her incarceration came late one afternoon of low visibility and gusty conditions. The first indication the Officer of the watch had was when soldiers were put on buoys and started to unshackle the lines. By way of explanation a P.L.A. launch pulled alongside and by loud haler informed the ship that they had received permission to sail immediately, and that a tug had been allocated to assist them as far as Woosung.

This provoked an immediate scramble in the engine room to raise steam.

The four P.L.A. soldiers on board were in a panic to read the ships draft before she got underway. Refusing all help from the Quartermasters their amateurish attempt to rig rope ladders over the bow and stem, resulted in the stem ladder not properly secured, dunking the soldier in the river, and having to be pulled on board by his companions wet and dripping.

The tug arrived as promised (ex U.S. Army) and in an act of carelessness allowed the ship to surge just as the stem lines were being retrieved from the buoy trapping the second Chinese Bosun’s arm. He was placed in the ships hospital with brief first aid until the ship was underway when more attention would be available. He was afraid he would be put ashore in Shanghai for treatment and was voluble at any suggestion his injuries were serious.

It was dark and raining heavily when Nankin reached Woosung where the River Pilot and the four P.L.A. guards left the ship.

The seals on the radio room were broken and its contents retrieved allowing ‘Sparks’ to make contact with the next port, Hong Kong and advise them of the critical state of the fuel and water. It also provided a much needed weather report, The weather for the run out of the Yangtze River to Hong Kong was going to be bad with storms, rain and high seas, as well as Nankin being a virtually light ship.

Hong Kong harbour was a welcome relief from the maelstrom outside which the ship had been battling. The fuel barge and water boat were alongside as soon as the quarantine inspections had finished. Welcome fresh fruit and vegetables were next. The Chief Engineer’s maintenance list was extensive however with limited south bound cargo, it presented an opportunity for local painting contractors to work on the hull.

The Chinese store man would look after the paint distribution in place of the Second Bosun who was now in a local hospital with a broken arm after the accident in Shanghai departure frenzy. He rejoined the ship on its next voyage north still in plaster.

Nankin’s stay in Hong Kong was fore-shortened by a weather alert from the colony’s meteorology bureau suggesting all ships that could, should consider leaving the harbour to avoid approaching bad weather that could possibly become a typhoon.

Nankin took the weather threat seriously, hurriedly completing maintenance items being undertaken and joined the line of ships leaving the harbour.

In preparation for her next three ports where the cargoes were logs of various tonnages, the crew overhauled and painted the cargo gear. The stock take of the paint quantities left the Chief Officer scratching his head with “These can’t be right!” The quantities were checked again and produced a similar result.

At the port of Sandakan (now Sabah Port) a trip around the ship at anchor to read the draft quickly revealed to a furious Chief Officer the reason why there was a discrepancy with the paint quantities. Instead of a clean black port side hull with red boot topping and white band there was now a muted purple hull, orange boot topping and khaki band. The contractors in Hong Kong must have run out of paint and couldn’t or wouldn’t look for someone to re-supply the quantities needed to finish the job. So, they had made their own with what they could lay their hands on at the time. The ship’s hurried departure had prevented the mistake from being discovered, and any rectification work taken.

For the next two ports the ship had to take the labourers with it, they lived on the no. 5 hatch under a cargo tent, cooked their own meals with their own food. However it was a security nightmare, with all cabins, the bridge and chart rooms locked and the keys with the Ship keeping Officer. A Quarter-master was on patrol day and night as well as one on gangway duty.

Bohihian Island was a port in name only. In essence it was a position on the chart of Darvel Bay, the shore line barely visible. The logs to be loaded were formed in a raft and towed to the ship by an ancient steam tug burning timber off cuts from the mill. Work loading the logs was during daylight hours for those that were destined for the holds and for the deck cargo. It was ‘Job and finish,’ safety precautions by the labourers were non existent, no foot wear and only a brief loin cloth for covering.

Accidents were all part of a days loading and Nankin’s first was on the third day at anchorage. A log had slipped in the wire sling as it was being lowered into the hold crushing one of the labourers below. Work stopped while the injured man was hoisted out of the hold. The injuries were such that the Captain was forced to radio for assistance the reply when it came was from the Americans, who promised assistance in two hours. The Americans were as good as their word.

Two hours later the ship was overflown by a large flying boat with American markings. An exchange of wireless messages asking for identification and if the patient was still alive and then the wind and sea state conditions ensued. The flying boat landed on a stretch of water further out in the bay and motored in towards the ship.

From a midships door on the aircraft a small inflatable boat with two figures in military fatigues headed towards the gangway, a brief examination of the patient and in reply to questions from the Master, “We’ll take him,” the injured man was stretchered to the steam tug waiting alongside and towing the inflatable headed out to the waiting aircraft, which then took off over the distant shore. Work then resumed on the last of the log rafts.

Wallace Bay was a tidal estuary and the anchorage was opposite the sawmill. Nankin was to load the logs that would be her deck cargo. Sailing time would depend on the state of the tide so she could clear the bar at the estuary entrance. The logs to be loaded were in a log pond instead of a log raft as with other ‘ports’. The pond was held together with wire rope that had seen better days! Sailing time now set to catch the tide and the ‘turning gear’ in operation. The last of the deck cargo loaded and secured, the labourers waiting with their luggage to be ferried across to the saw mill for transport back along the coast for their next job.

A sudden blast of an engine room klaxon, accompanied by warning bells and flashing lights, with off duty engineers jostling for the engine room ladders, demolished the ‘On the way home’ feeling at last instead of ‘What now’ with quiet resignation to the changing circumstances.

A log from the last remaining log pond with its wire rope harness had drifted into the slow turning propeller and had become jammed, wrecking the turning gear in the process. The log was not visible in the murky water and had escaped detection in the final inspection before the turning gear was started. Nothing could be attempted to clear the obstruction until daylight, and low water. It was then nine hours of concentrated and dangerous work, with the help from workers from the sawmill and some labourers waiting for their transport.

Nankin had to await high water before she could leave the estuary. Even then there were anxious moments as she touched the mud of the bar, on her way to the Celebes Sea and her next port of Tarakan for fuel.

Any hope of a quick tum around at Tarakan was dispelled by the Indonesian Pilot who pointed to the line of ships waiting for the single berth at the refuelling terminal. Nankin was the sixth in line which would mean a wait of some thirty hours.

An exchange of radio messages with the company in Australia deemed that she still had some cargo space available. So after Tarakan, Nankin had to call at Rabaul before returning to Australia. A further six days to the voyage depending on the turn around at Rabaul which had a notorious reputation for delays, and in that, they were not disappointed. Nankin had to anchor outside the port while a motor vessel occupying the only wharf completed unloading and waited for repairs to her engine before she could load and sail for Brisbane using the inside passage of the Barrier Reef.

The Barrier Reef Pilot, boarding at the Thursday Island’s pilot station for the run to Brisbane made an innocent comment about how Nankin had been expected at the station weeks ago brought some ribald comments from those on the bridge at the time. He quickly changed the subject.

Nankin completed her discharge of the logs and sawn timber at the main Australian ports, and began loading for the return voyage to Japanese ports. It was not until she called into a port in Newcastle N.S.W. to load steel plate that it was revealed she would be spending a white Christmas in Shanghai, China once again!

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item