If ever there was a man-made disaster it must surely be that of the tanker Exxon Valdez.

I recall seeing the ship in Singapore Roads under her new name, and thinking if all onlookers really knew what they were looking at? I must admit I didn’t, thinking it was just another of the many non-descript VLCC tankers at anchor, until informed otherwise by the marine Pilot that was taking my ship into Singapore at the time.

The vessel was built in October 1986 by the National Steel and shipbuilding Company, San Diego, California, for the Exxon Group and was 214,861 dwt. The Exxon Valdez will go down in infamy as the vessel responsible for causing major oil pollution in one of the world’s most pristine areas, Prince William Sound, Alaska, when she grounded on Bligh Reef on 24th March 1989, rupturing her cargo tanks and spilling almost 37,000 tonnes of crude oil. It is considered to be one of, if not the worst oil spills worldwide, in terms of damage to the environment.

The Exxon Valdez had secured alongside the Alyeska Marine Terminal at 11:30 pm on 22nd March 1989. The loading of crude oil was completed late the following day, the ship departing from the Alyeska Pipeline Terminal at 9:12 pm 23rd March 1989, loaded with 1,264,155 barrels of crude oil. The vessel was under the command of Captain Joseph Jeffrey Hazelwood.

The captain retired to his cabin at 9.25 pm. The Marine Pilot and Third Mate were accompanied by a single tug for the passage through the Valdez narrows, a journey of about 7 miles. The Pilot left the bridge shortly after the vessel cleared the narrows, at 11.24 pm. At this point, the captain was called to the bridge. The Third Mate was assisting the Pilot to disembark from the vessel and was not on the bridge, leaving the captain, as the only officer on the bridge. At 11.25 pm Exxon Valdez reported that the Pilot had departed from the ship.

Having returned to the bridge, the Third Mate advised traffic control and decided to deviate from the predetermined traffic lanes to avoid small icebergs which were a common occurrence in these waters. However, the Exxon Valdez significantly deviated from the set course and traffic lanes to avoid ice, contrary to regulations. The vessel was placed on a due south course and set on autopilot. At 11.47 pm the vessel left the traffic lanes eastern boundary.

The Third Mate had been on duty for 6 hours and was scheduled to be relieved by the Second Mate. However, due to the long hours that the Second Mate had worked, he was reluctant to wake him, and remained on duty himself. The Third Mate was the only officer on the bridge for most of the night, in violation of company policy.

At around midnight the Third Mate began to manoeuvre the vessel into the traffic lanes. At the same time, the lookout reported that the Bligh Reef light appeared far off the starboard bow at about 45 degrees. This was problematic given that the light should have been off the port side.

The Third Mate ordered a course change, as the ship was in danger. Captain Hazelwood was quickly called to the bridge, but before their conversation could finish, the ship grounded heavily on Bligh Reef at 12.04 am on 24th March.

Carried by its own momentum, the ship ended up perched amidships on a pinnacle of rock. 8 out of 11 cargo holds were ruptured allowing 5.8 million gallons of oil to drain from the ship within 3 hours and 15 minutes. For more than 45 minutes after the grounding, the captain attempted to manoeuvre the ship free of the reef, despite being advised by the Chief Mate that the vessel may not be structurally sound without the reef supporting it. After numerous attempts to dislodge the ship under her own power, Captain Hazelwood radioed the Coast Guard informing them of the grounding.

During the first few days of the spill, heavy sheens and scum of thick black oil covered large areas of the surface of Prince William Sound. Beginning three days after the vessel grounded, a storm pushed large quantities of fresh oil onto the rocky shores of many of the beaches in the Knight Island chain.

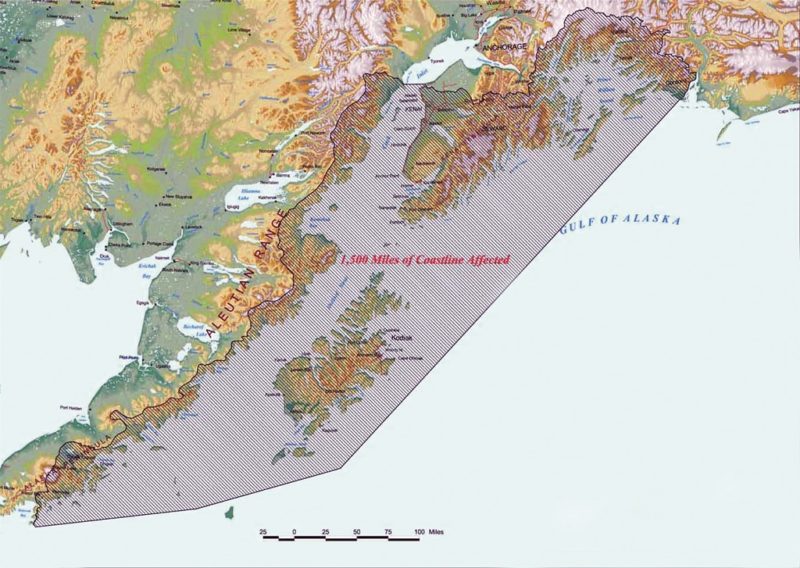

The damage caused by the tar like oil caused significant pollution to the surrounding coastline, as far distant as 200 miles causing loss of life to marine and wildlife not to mention loss of income to local industries, in particular the fishing sector, which continued for many years.

A court of inquiry found, Exxon Shipping Company had failed to supervise the Master and provide a rested and sufficient crew for Exxon Valdez . The National Transport Safety Board found this practice was widespread throughout the industry, prompting a safety recommendation to Exxon and to the wider shipping industry. They also concluded the Third Mate had failed to properly manoeuvre the vessel, possibly due to fatigue or excessive workload.

The NTSB also stated that the Exxon Shipping Company had failed to properly maintain the Raytheon Collision Avoidance System (RAYCAS) radar, which, if functional, would have indicated to the duty bridge officer an impending collision with the Bligh Reef, by detecting the “radar reflector,” placed on the rocks immediately adjacent to Bligh Reef, so positioned to assist ships with their navigation.

Captain Joseph Hazelwood, who was widely reported to have been drinking heavily that night, was not in charge on the bridge when the ship struck the reef. Exxon blamed Captain Hazelwood for the grounding of the tanker, but Hazelwood accused the corporation of making him a scapegoat. As the senior officer in command of the ship, he was accused of being intoxicated and thereby contributing to the disaster, but he was cleared of this charge at his 1990 trial after witnesses testified that he was sober around the time of the accident. Ultimately, Captain Hazelwood was convicted of a lesser charge, negligent discharge of oil (a misdemeanor), fined $50,000, and sentenced to 1,000 hours of community service.

Ironically, Captain Hazelwood received two Exxon Fleet safety awards for 1987 and 1988!

After repairs, Exxon Valdez was renamed Exxon Mediterranean , then Sea River Mediterranean in the early 1990s, when Exxon transferred its shipping interests to a new subsidiary company, River Maritime Inc. The name was later shortened to S/R Mediterranean, then to simply Mediterranean in 2005.

The ship then served in European, Middle East and Asian regions. In 2005, it was reflagged to that of the Marshall Islands.

Since then, the European Union regulations have prevented tanker vessels of single-hull design such as the Valdez from entering European ports.

In early 2008, Sea River Maritime, an ExxonMobil subsidiary, sold Mediterranean to the Hong Kong-based shipping company, Hong Kong Bloom Shipping Ltd., which renamed the ship Dong Fang Ocean, under Panamanian registry. In 2008, she was refitted and converted from an oil tanker to an ore carrier. In 2011 she became Oriental Nicety.

In 2012 she was renamed Oriental N and laid up at Dalian. She arrived at Alang to be broken up on 9th May 2012 but was refused permission to dock in India because it had toxic contamenents onboard. She finally was allowed to beach on 2nd August and was broken up by Priya Blue Industries.

This disaster resulted in the International Maritime Organization (IMO) introducing comprehensive marine pollution prevention rules (MARPOL) through various conventions, which have since been ratified by the world’s maritime nations, and duly implemented. According to some reports, the oil, eventually covered 1,300 miles of coastline, and 11,000 square miles of ocean.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item