On 4th August 1914, King George V declared war against the German and Austro-Hungarian empires, on the advice of the British prime minster, Mr. H. H. Asquith. During the war, efforts were quickly made to try and prevent food shortages and any labour shortfalls across Britain, and on the Continent. It soon became paramount that communications and supplies were vital and needed to continue being transported across the Channel. The War Office soon realised it would be advantageous if the British Expeditionary Force (B.E.F.) were to have its own railway service, which would allow locomotives and rolling stock to be handled more easily, facilitating the rapid transportation of supplies to the Frontline. By January 1915, the authorisation was given to establish the Railway Operating Division (R.O.D.), with many of the locomotives and rolling stock being provided by the South Eastern & Chatham Railway.

In December 1914, the Inland Water Transport (I.W.T.) Section of the Royal Engineers was formed, and became responsible for operating and developing the transportation of supplies on the canals and waterways in northern France and Belgium. The I.W.T. had initially been operated under the Director of Railways, but with the development of the I.W.T. a Special Directorate was later formed in October 1915, and it later became known as the Inland Waterways and Docks (I.W. & D.) Directorate. Transportation services included railways, roads, inland water transport, and docks, with the personnel being provided by the remainder of men, recruited into the Royal Engineers until September 1916. A Director-General of Transportation was appointed and made responsible for controlling all these services.

The majority of the officers in the Royal Engineers were drawn from members of the Institute of Civil Engineers, Architects and Railwaymen. One man, Gerald Holland, had been Dock and Marine Superintendent for the London & North Western Railway (L. & N.W.R.) Company at Holyhead, and as a result was made responsible for establishing the I.W.T. service on the Western Front. In December 1914, he was appointed Lieutenant Colonel in the Royal Engineers, and later became Assistant Director of the I.W.T in France. By 1916, Holland had become Director of the I.W.T. and was Director General in 1917. Gerald Holland’s influence on the I.W.T. and the vital role of canals in France also stretched to the development of Richborough Port in Kent. With his involvement at Richborough he would eventually become responsible for pioneering the first cross-Channel ferry services, which were established at both Richborough Port and Southampton. By November 1918, units under the Order of Battle for the I.W. & D. were being listed with a Depot Headquarters at Richborough, which consisted of camps that had workshops and shipyard companies, construction, marine, traffic, train ferries, stores, accounts, Home Depot, and tug masters.

The site of Richborough in Kent had been just one of many sites in Britain that came under the new regulations, enforced by the Defence of the Realm Act, which gave the government wide-ranging powers throughout the war, including the power to requisition land and buildings that were required for the war effort. Even before the war, plans had been created for the development of the Sandwich Haven, which would see the transportation of coal being shipped out from the newly developed Kent Coalfield. By 15th January 1916, an official document proposed, “to take up an area in the County of Kent between Sandwich and Ramsgate – recently used by Messrs. Pearson & Sons Ltd. – as a concrete block yard and gravel pit for the purpose as a store yard for Inland and Transport”. The large quarry, which had flooded and become Stonar Lake, was originally excavated for the ground material that was cast into the concrete building blocks that had recently build the construction of the harbour arms at Dover. In 1894, when Lord Spencer was First Lord of the Admiralty, a scheme was proposed for the enlargement and new features costing an estimated £2,000,000 to £3,500,000 for Dover Harbour. The budget was incorporated into the Naval Works Bill, which was passed, and as a result the Admiralty went ahead by inviting interested tenders. Specifications were drawn up by the Admiralty engineers, Messrs. Coode, Son & Matthews. On 5th April 1898, the tender Pearson & Son Limited, were awarded the contract. The firm’s director in charge for the chief part of the work was Mr. Ernest Moir.

The Royal Engineers visited the Sandwich Haven and work soon began with surveys and planning for the development of the site along the edge of the River Stour. Richborough and Stonar had been chosen for their geographical location on the coast, along with the limited facilities, which could easily be developed, as well as the site being one of the shortest distances from mainland Britain to the Continent. The South Eastern & Chatham Railway also passed within one mile of the site, on the mainline railway route between Ramsgate and Sandwich. The site was mostly undeveloped and the surrounding landscape allowed for a fresh development and expansion for military stores and warehouses. In February 1916, two officers and 50 men had arrived at the Sandwich Haven. By May 1916, four officers and 330 other ranks had arrived at Richborough and Stonar to begin preparations for the site, and the development of what the military would soon christen the site as “Richborough Port”. The whole complex would cover a total area of 2,200 acres, providing enough space for 172 acres of accommodation camps, 271 acres for stores and salvage depots, and 111 acres for workshops and shipyards. The first development to have begun at Richborough Port was the construction of barge slipways, with the initial excavations having started in June 1916. The slipways would be used for the assembly of “Ac” cross-Channel barges that would transport essential material for the war effort. One of the largest and most impressive developments at Richborough Port was the construction of a New Wharf, which would have specially designed electric cranes used for loading of the cross-Channel barges, which had begun to be constructed in December 1916. The construction of the New Wharf had commenced on 2nd June 1916, with the initial placement of 1,853 sections of large metal sheeting being driven 22.5 feet into the ground, with king piles driven an average of 27.5 feet into the ground. The entire New Wharf covered a straight frontage of 2,374 feet (723 metres), and was completed in sixty-one days.

As the war continued it soon became apparent that the amount of equipment being transported by the barges to France and Belgium would rapidly increase. By early 1917, Sir Eric Geddes was appointed as the Inspector General of Transportation, with Sir Guy Granet becoming the acting Director-General of Railways at the War Office. The Army Council had adopted a scheme, which was presented by Sir Granet, to provide the development and operation of a train ferry service between Britain and France. Train ferries had been used in North America for inland water transportation, and a few other countries such as Denmark in the Baltics, prior to the First World War. A regular passenger ferry service had already been operating across the Channel between Britain and France from Dover and Folkestone, but no pre-existing cross-Channel train ferry services had yet been established. It was soon realised there would be some challenges ahead, if a cross-channel ferry service were to be developed. One of the main challenges highlighted was to ensure the return of railway wagons on an outward journey from Britain, being unloaded wherever possible, with the cargo also possibly requiring repair, or salvage. However, it was decided that the disadvantages were outweighed by a need to have the necessary facilities, providing a rapid transportation service across the Channel.

On 17th January 1917, the decision was made, and the official notice given for the design and construction of three specially-built cross-Channel train ferries. In addition, was the order for the necessary plans and surveys to be made at each of the suitable sites where the train ferry terminals would be located. Two of the train ferries were designed by Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Company, Limited, of Walker-on-Tyne, while the contract for the third train ferry was given to the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company, Limited, of Govan. The two sites chosen for the siting and development of train ferry terminals in Britain were at Richborough and Southampton. Considerations had been proposed for the use of existing harbour facilities at Dover, Ramsgate and Folkestone, all within just 20 miles of Richborough, but it was felt these harbours were already congested with their involvement in the war effort. The site at Southampton was chosen instead of using Portsmouth, Itchen River, Hamble River, Langston Harbour, Chichester, and Keyhaven. The train ferry terminal at Southampton was situated close to Southampton Royal Pier, and was considered because it was felt that no dredging would be necessary, along with there being ample space already available, allowing for the train ferry to easily manoeuvre. Sidings were soon built on reclaimed land along the shore, and a railway link made with the London and South Western Railway from Southampton West Station.

As mentioned, one of the most important aspects for the train ferry terminals depended on the range of tides. The difference in the level of the water and consequently the rail level on the decks of the train ferries could range between seven to fourteen feet, resulting in a difference of 7 feet higher at high tide and 7 feet lower at low tide, in comparison to the level of the rails on the shore. The draught of the ferries could vary depending on the amount and distribution of the individual cargo, with the possibility of the vessel listing if either the port, starboard, or even the bow and stern of the vessel was more or less loaded, especially at the point of loading and unloading. As a result, it would mean that one rail could be higher or lower than the other, making it very difficult and challenging for loading and unloading the trains and other rolling stock.

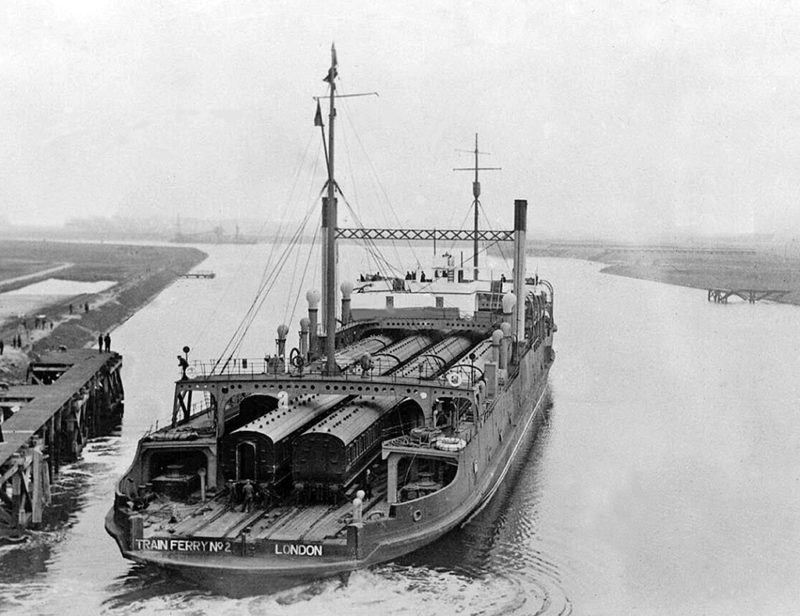

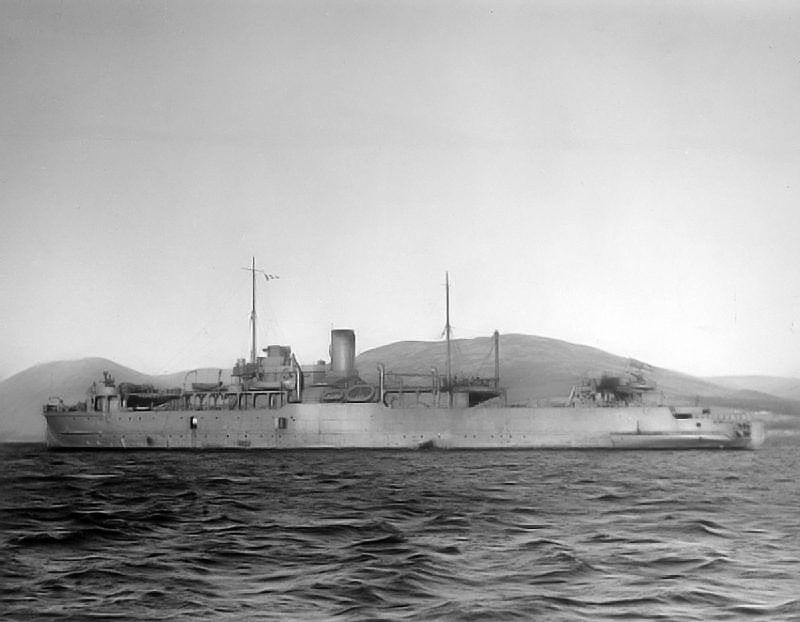

Each of the train ferries, which were designated and named Train Ferry No.1, Train Ferry No.2 and Train Ferry No.3. Train Ferries No.1 and No.3 both operated in conjunction to and from Richborough Port, while Train Ferry No.2 operated to and from Southampton. The three train ferries had the same design and dimensions, regardless of where they were operating. Each vessel measured 363 ft. 6 inches in length, and 350 ft. between perpendiculars. Their breadth over fenders measured 61 feet 5 inches, had a 58 feet 6 inches breadth moulded, and a draught of 17 feet. Once loaded their draught forward was 9 feet, and a 10 feet draught loaded to the aft. The deadweight on these draughts was made up of 850 tons of cars and freight, 80 tons of fuel, 5 tons of stores, along with the necessary crew and effects, 10 tons of food and water, 5 tons of fresh water, and 10 tons of spare gear on board, all amounting to approximately 900 tons. The gross tonnage was 2,672 tons, and a net resister tonnage of 1,533 tons. All three train ferries were designed with a single deck, with a forecastle and port and starboard sides that could accommodate a roof if required, but a roof appears to have rarely been used. Each ferry was fitted with an upright stem, and the stern of the vessel was arranged to take an apron or bridge. They also had a forward shelter, or main flying bridge, with additional docking bridge decks. The main bridge on the vessel was amidships, which carried a chart and wireless room. The captain’s quarters were situated above the chart room. Propulsion was made by two sets of triple-expansion oil fired Howden engines, designed to be capable of propelling each vessel to a speed of 12 knots under ordinary working conditions. The decision was made to use oil rather than coal fired engines to help save space and accommodate for smaller boilers. The amount of oil used per hour whilst at sea was around 1.7 tons. The introduction of the train ferries saved in manpower, with 1,500 men required using conventional shipping from factory to France, in comparison to 106 men required with the train ferries. The average turnaround from the point of arrival to departure for a train ferry was stated as 30 minutes, with a record set at 19 minutes. The train ferries all had a mean draught of 9 ft. 6 inches and a full deadweight of 900 tons onboard. The accommodation for officers, engineers and crew was situated below the vehicle deck. Each vessel had cost estimated £190,000 to build. The most unusual cargo included tanks, and also two huge 300 tons, 12 inch railway mounted Mark IX guns, named ‘Scene Shifter’ and ‘Bosche Buster’.

Other than the captain and three executive officers there were four engineer officers and a wireless operator, along with a crew of thirty-seven petty officers, gunners and men. All crew were considered as military personnel. It wasn’t uncommon for the vessels to be attacked by enemy aircraft, especially when they were at Dunkirk and Calais harbours, which led to the Dunkirk site eventually being abandoned due to so many attacks being made. For their own defence, each vessel was fitted with four 12 pounder guns, with two fixed at the bow and two at the stern. Two of the guns were placed on two high angle mountings.

Each designated terminal had a huge iron gantry built, which provided a raising and lowered platform, known as the ‘Train Ferry Bridge’. These communicating bridges, or linkspan, were all partly of the same design, except for their lengths, which were all dependant on the exact location and port there were being used. An 80 feet bridge was used at Dunkirk, while Richborough and Calais both had 100 feet bridges. Southampton and Dieppe both had bridges measuring 120 feet in length. The bridge, or link span would be connected to a train ferry once the vessel was fully secured and moored up alongside the berth by using hemispherical bearings, which allowed not only for heel, but also pitching actions if a vessel was caught in a swell. At the land end, the bridge was supported by four steel wire ropes that worked from the 42 feet high iron gantry above. These enabled the bridge to be raised and lowered, adjusting to the height of the vessel and the changing tide. A winding drum was actuated through a reduction gearing mechanism by a 20-horsepower electric motor, running at 500 revolutions per minute. Hand gearing was also provided from a bridge above, operating 5-inch cables, with a breaking strain of about 120 tons.

Almost immediately after the Armistice of the First World War was declared the three train ferries continued to be used for transporting much of the returning salvaged material that had been found on the battlefields in France and Belgium. The three train ferries were later refitted, their hulls painted black and given buff funnels. It wasn’t too long before the eventual development of a new train ferry berth was built and proving a service at Harwich. The linkspan and gantry were dismantled at Southampton and transported to Harwich. However, during the voyage the load shifted and sank, leading to the iron gantry at Richborough Port being removed and sent to Harwich, where it still remains today, even though in a sad state of dereliction. On Thursday 24th April 1924, Train Ferry No.2 became the first train ferry to depart from Harwich, following the official opening ceremony. The fleet was completed with the addition of Train Ferry No.3, then Train Ferry No.1 arrived on 17th July 1924.

On the advent of the Second World War in September 1939, all three train ferries were requisitioned once again by the government. All three vessels were dry docked, degaussed and their compasses adjusted. They were initially used for transporting tanks, artillery and vehicles for the British Expeditionary Force. On 12th June 1940, all three vessels were sent to assist with evacuation troops from Valery-En-Caux, near Dieppe. Train Ferry No. 2 was sunk by German batteries opening fire. During mid-June 1940, both Train Ferry No.1 and Train Ferry No.3 assisted with the evacuation of the Channel Islands. Both vessels were taken over by the Royal Navy and renamed HMS Iris (later HMS Princess Iris) and HMS Daffodil. These names were chosen as reference to the two Mersey ferries, which had taken part in the raid on Zeebrugge in 1918. Both vessels were refitted and re-converted to oil firing. HMS Daffodil would eventually be lost after sinking on 18th March 1945. She had struck a sea mine the previous day, before attempts were made to beach her, which resulted in the deaths of thirty-three of her crew. Only Train Ferry No.1, or Princess Iris survived the war. She was renamed again as Essex Ferry and ran between Harwich and Zeebrugge from 16th August 1946 until being scrapped in 1957, having been renamed yet again as Essex Ferry II.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item