1918

After a period ashore in London, studying at Marconi House in the Strand for his PMG 1st Class certificate, Neil Semple returned to sea.

The following ten years were not to be very happy ones, partly because all my ships were pretty undistinguished cargo boats, tankers, and downright tramps. I think I should possibly be thankful that I was always in employment in the twenties because it was a period of mass unemployment. Salaries became stagnant and actually gradually decreased over those years. Conditions on the tramp ships also deteriorated as shipowners tried to save on such things as seamen’s food, the upkeep of the ships themselves, reductions in manning, and the most serious of all, there was a tendency for ships to be overloaded. Several serious marine disasters during the decade following the war were directly attributable to poor maintenance and overloading, the latter particularly being quite illegal.

My first ship following my period at school was a Donaldson Line cargo ship, the Argalia which had started life during the war as a standard ship named War Kestrel. I was to sail on several of this class of ship during the next twenty years. They were of the three island type, very strongly built, with absolutely no frills. The Argalia had a completely open bridge on which was sited a steering wheel, a binnacle, and one telegraph, absolutely nothing else in sight. One of my mind boggling memories is of taking weather reports up to the bridge during a howling North Atlantic westerly. The scene resembled a half tide rock with the old man and third mate crouching behind a wisp of canvas dodger, while the man at the wheel looked to be frozen to his job. He had so many clothes and oilskins on that he looked like something from outer space through the flying spume and the howl of the wind. I was glad to get back to the comparative warmth of the radio room which was only one deck down on the lower bridge. After my passenger ships of beloved memory, I was to be really taught what bad weather on a small ship could be like. The winter of 1919-20 was a bad one on the North Atlantic, and probably made a seaman of me at last. I was never afraid of anything the sea could do thereafter.

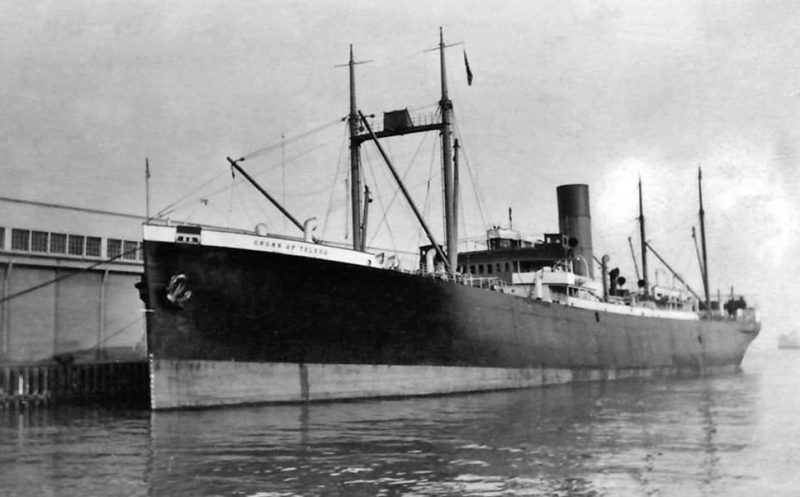

The single trip on the Argalia ended in Liverpool where I was quickly appointed to rather a nice ship with a beautiful name, the Crown of Toledo. She was a Glasgow registered vessel of 5,806 gross tons belonging to Prentice, Service, & Henderson, a company which was bought over by T. & J, Harrison of Liverpool at the end of the voyage. This was sad because the Crown Line was a good company with a very contented and loyal staff. The trade was mostly to the west coast of the United States and so I looked forward with keen delight to the prospect of seeing the Golden State with my own eyes.

The Crown of Toledo was a comfortable and well found ship with a rather unusual radio room situated off the dining saloon. It had been a passenger room at some time and was quite commodious. But it really was pretty unsuitable inasmuch as it was a combined radio and sleeping berth with two bunks stacked on the inboard side. Although this was the first time I had come up against such an arrangement, the practice was widespread. Wireless at sea was still in its infancy and older ships which had been built prior to the advent of wireless were required to improvise to some extent. The bad feature of this practice was that, as the emergency storage batteries were fitted in a cupboard in the radio room, one was living constantly in an atmosphere polluted by sulphuric acid fumes. At a later date, regulations were enacted putting a stop to this and it became the law that batteries should be housed external to the radio room. However, we were not very fussy about such things and I suppose there was a good deal of ignorant tolerance of our living conditions in those early days. I was now the ‘senior’ and had a first trip ‘junior’, an Englishman named Jefferies who disappeared from my life without trace following the voyage. I can’t remember if he was unhappy or not about his shipmates because the ship was unashamedly Scottish, the Chief Officer came from the island of Bernera and Macleod the 2nd Mate was actually from Iona. Many of the deck hands were also from the islands and much Gaelic was spoken on board. Being from Kintyre myself, I was accepted grudgingly as one of them but the fact that I was non-Gaelic speaking rather weighed against me.

The Crown of Toledo made a good passage south-westward from Liverpool to Panama, where we bunkered at Cristobal, near the port of Colon at the Atlantic end of the new canal which, although not completed, was now navigable by day.

After a pleasant voyage of about ten days we arrived at San Pedro, the port of Los Angeles which at that time in 1920 was a very pleasant little town with a small population of around 5,000 and a very good harbour which had a large proportion of the US Pacific fleet at anchor in the roads. Our stay there was very short, about two days and so we were not able to do any sight seeing, mainly because the captain would not issue any money and, in any case, we had many more ports to go to and it would not have been wise to start spending too soon. It must never be lost sight of in those memoirs that I was always hard-up, a fact that greatly circumscribed my sightseeing throughout my time at sea. As radio officers we had much free time in port but lacked the resources to make as much use of that time as we would have liked. However, I was always a good walker and I did not really miss all that much during the period between the wars.

We proceeded to San Francisco at the end of our short stay in San Pedro and that was the place that I had been saving up for. It must be said that this beautiful city came up to all my expectations and remains to this day my favourite foreign port, although some others did run it very close. The Golden Gate entrance to the magnificent harbour was very much as I had imagined it through the eyes of R. M. Ballantyne and other writers of boy’s books. It was not marred as now with a huge suspension bridge (sister to our own Forth road bridge) and all the crossings in the splendid Bay area were by ferry. It would be difficult to imagine a better landlocked harbour or a bigger one. The shape of it can only be likened to a plan view of a gigantic vice with the jaws opened, with San Francisco City and the Mount Tamalpais peninsula providing the extremities. The Bay area itself runs roughly north and south and is approximately 60 miles long from Palo Alto in the south to about Sonoma in the north. The greatest width is at San Leandra where it is about ten miles. Right ahead coming through the gate is the famous island of Alcatraz which was at that time a maximum security prison, for the more desperate type of criminal. It has since been evacuated and put to other uses.

Across the Bay from San Francisco city lie the twin towns of Oakland and Berkeley the latter being the home of the University of California, probably the biggest in the World today. To the north, still inside the Bay lies San Pablo Bay through which are the approaches to the famous Sacramento River, made memorable during the gold rush of 1849. At that time San Francisco harbour was crammed full of sailing ships without crews. They had all ‘skinned out’ for the diggings, immortalised by the old sea-shanty ‘there’s lots of gold so I’ve been told on the banks of the Sacramento. During our stay in that delightful port we thoroughly explored the city and its environments. A day was spent in the splendid Golden Gate Park which looked out on to the Pacific and the new fine theatres and cinemas were well patronised every night. Sometimes we very daringly returned to the ship by way of the Barbary Coast which was the nickname of the dock road whose real name was the Embarcadero.

There were plenty of sailor honky tonk saloons where one could dance and drink and hob-nob with the local demimonde, but I do not remember any of us being any the worse. It was usual in most ports for us to go ashore in groups of at least four, not for protection I hasten to add, but just from sheer mateyness. I suppose hoodlums would hesitate to attack four hefty sailor men at the same time, but the eventuality never arose.

After a stay of about a week we set off for British Columbia, the western-most state of Canada, where a very pleasant surprise awaited me. I have to relate the fact that I had close relations in Vancouver Island, where we were now bound, and it was pretty certain that my mother would have apprised them of my approach. These were my Aunt Jessie McEwan, my mother’s oldest sister all the way from Glasgow, and her now large family of three boys and two girls, John, James, Bill, Janet and Jean. The family had immigrated to Canada from Glasgow around 1902, soon after I was born, and we had kept in touch with them to some extent. My uncle, James McEwan had died some years earlier leaving my aunt with the difficult task of bringing up a young family on her own. She was an admirable woman in every way and coped with the situation splendidly. Oddly enough, we had met John the oldest boy during the war when he came over with the Canadian Expeditionary force to fight in France. He would be about 22 at the time and he spent two leaves with us at High Ugadale farm.

After about a week’s stay in Victoria, the Crown of Toledo set off for the mainland city and port of Vancouver, the western terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway on the stretch of water called Puget Sound.

The west coast of British Columbia is not unlike the west of Scotland in many respects. It is studded with islands the main one of which is Vancouver Island and with another considerable groups further north comprising of Prince Rupert Island, Queen Charlotte Island and Prince of Wales Island. Puget Sound is formed by the channel to the south and east of Vancouver Island which itself fits into a large indentation on the North American coastline between Cape Flattery and the entrance to the Fraser River. The southern side of Puget Sound is bounded by the State of Washington and the Sound itself bites deeply into that state towards the great port of Seattle and, further on, Tacoma.

The Canadian Pacific Railway and the Canadian National Railway both ran a fleet of small coastal type passenger ships to serve the various islands and also to maintain a commuter trade between Victoria, Vancouver and Seattle. The CPR ships were all ‘Princesses’ and resembled greatly the Clyde passenger ships. Indeed, one of the fastest in their fleet was none other than the old Queen Alexandra which they acquired from the Clyde some time around 1910. This ship was historic for being the first or second turbine steamer to be built and could do over twenty knots, a great speed in those days. The turbines were direct drive then and generated a high pitched hum which could be heard from afar. It was somewhat nostalgic when I stood beside the old Queen in Vancouver, now named Princess Patricia, and thought of the long summer days in long-ago, far-off High Ugadale, when we boys toiled in the hay fields and how we welcomed the sound of the Queen Alexandra as she rounded the north of Arran on her way from Fairlie to Campbeltown. The sound gradually rose to a high whine and, mingled with the strains from her German band it told us that it was about a quarter past three and that we only had about three more hours to do at that accursed haymaking.

She had come out to Vancouver under her own steam round Cape Horn and was said to still have the same Chief Engineer who had brought her out. She continued for many years as the Princess Patricia, some times on the three-cornered run of Vancouver, Seattle, Victoria but latterly as the Nanaimo boat from Vancouver.

Vancouver itself proved to be a most interesting and pleasant place to sojourn in and we did the usual round of picture shows and other pleasure spots. The long street from the dock area up town known as Hastings Street had a number of small dancing cafes when one could have a glass of beer and dance if one could find a partner. That wasn’t all that easy because most girls were with escorts. However, we weren’t all that fussy and I never minded watching. Canadian drinking laws were even odder than those in Scotland and spirits were not on sale at all in the cafes, which maybe was not a bad thing.

From Vancouver we went on to Seattle, the largest town and chief port of the most north-westerly state in the American mainland, Washington, and a few days later to Tacoma, some distance further into the eastern end of Puget Sound. I remember little of either place except for their splendid ‘totem poles’, the one in the centre of Seattle being a very fine and very high specimen of this colourful sculpture in wood. From this area there is a magnificent view of Mount Rainier, one of the highest peaks in the northern Rockies. Little remains to be said on this most interesting and happy voyage which ended on a note of sadness.

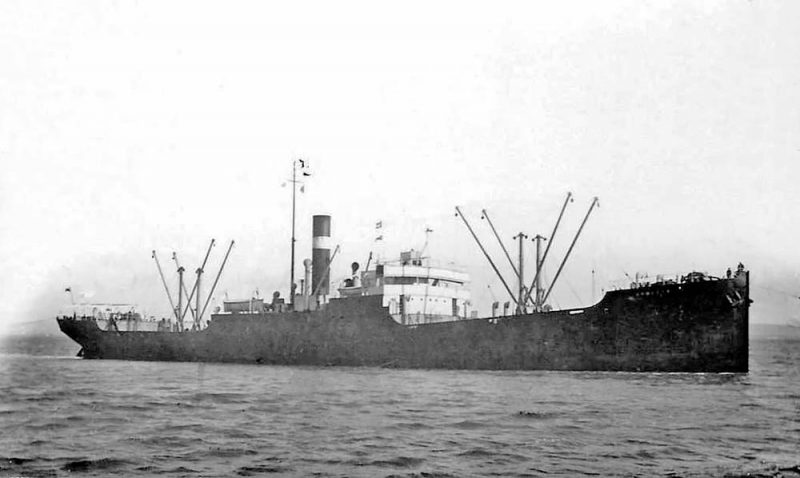

As I told earlier, the Crown of Toledo arrived home in Glasgow during 1920 where it became known that the company of Prentice Service & Henderson had been bought over by the Harrison Line of Liverpool. This created a good deal of gloom among the mates and engineers because transfers of ownership often entailed redundancies. This did not affect me in any way of course. Almost the only advantage of being employed by the wireless company was the fact that, although owners changed, the ships remained and we remained with them. I heard later that the beautiful name of Crown of Toledo was changed to Craftsman to bring her into line with the rest of the Harrison fleet. However, I was not permitted to keep my berth on the newly named ship but soon found myself back on the Western Ocean on a sister ship to the unlamented Argalia. My new ship was the standard type Cabotia (ex-War Viper) of the Anchor-Donaldson Line on which I did three six week voyages from Glasgow/Greenock to Quebec and Montreal. It was what we came to call the ‘Whisky’ run because the greater part of our outward cargo was that well-known produce of Scotland. The ship literally reeked of the stuff and, I am sorry to relate, so did many of the crew. It was difficult at times to know who had been drinking because everybody on board smelled of whisky.

I’m afraid that a good deal of the cargo found its way into the various cabins on board and it seemed that during loading, cases were often broken accidentally and many loose bottles became fair game for any enterprising seaman who happened to be around. The stevedores themselves in Glasgow drank a good deal of the stuff while working in the holds and the watching mates and apprentices had the unenviable task of rescuing loose bottles from broken cases. It was probably inevitable that much of this ‘rescued’ whisky remained lost to the shippers or consignees. Some of this whisky was pretty savage stuff, being 80% proof and not all that old.

With it all, the three voyages were completed very successfully and nobody was much the worse. I expect that 99.9% of the cargo reached its destination safely in spite of the predators on the way. My best friend on the Cabotia was Keldie the third mate. He was a photography expert and also had a gramophone with a huge horn and an inexhaustible stock of records. Many hours of my off-watch periods were spent in Keldie’s room where we always seemed to be either developing, printing, or enlarging photographs. He really terrified me one day in Quebec when we did an expedition to the famous Montmorency Falls. He went to such extremes in his efforts to get a good view into the falls from the top that I almost gave him up for lost. These are very much higher than Niagara but without Niagara’s spectacular width. The famous Quebec Bridge was just completed and we walked over it one day. Earlier in any career during the war I had seen this bridge in the course of construction, with only the two end sections in place. It was a single span version of the Forth Railway Bridge and had been modelled on the same cantilever plan. I still have one of Keldie’s snaps of the bridge taken that day.

Another friend on board was one of the apprentices, Neil Mackinnon, a Govan boy and one of the nicest chaps imaginable. He was always laughing at something and there was never a dull moment when he was around. The fact that he later became chief Marine Superintendent of the Donaldson Line never surprised me a bit. The grapevine of the sea tells me that he now lives in retirement in Kirkintilloch, but, regrettably, I never saw him again after I left the Cabotia towards the end of 1920. The Donaldson Line carried a goodly number of Hebrideans among the crews, and was called by some the Tiree navy. It was a very sensible custom for any shipping company because those men were superb seamen and not subject to the usual bad behaviour in port which typified the general run of British sailors and firemen.

I always remember the Chief Engineer of the Cabotia, not because I liked him very much but because of his playful ways. He was a typical Clyde side type of character with the stamp of years as a fitter in Fairfield yards writ large all over him. His name was Fernie and he had been 2nd on the Cassandra prior to being promoted to his first chief’s job. He was always squaring up to people and also frequently handed out ‘clouts’ which if not avoided were quite painful. One day he physically attacked the mate, McLean, a heavily built, slow spoken Mullach, who was fair game for Fernie most days of the week. Suddenly he got too close to his victim and the next moment found himself held in a mighty embrace from which there was no escape. After maybe two minutes or so the mate carried Fernie’s inert body over to number 5 hatch and laid him down as carefully as if he was a baby being put to bed. Then he walked away still smoking his pipe which had been between his teeth throughout. That was the last of the chief’s capers. He was probably three stone heavier than the mate, but also maybe about only half as strong.

On the last voyage homeward bound we had the makings of a tragedy on board when one of the apprentices, John Sherriff was taken quite seriously ill. We were about half way across the Western Ocean when this happened and it soon became apparent that the resources of the ship’s medicine chest were inadequate to meet the emergency. Also, the booklet called ‘The Shipmasters Guide to Medical Care’ did not seem to be much help. John had some sort of stoppage of the bowels which could not be put right by all the valiant efforts of the captain and this was where I came in. It was my first experience of summoning help by radio and I was deputed to send a long radio telegram to the appropriate medical authority in the UK describing the boy’s illness and symptom and asking for medical advice on his treatment.

This transmission was accomplished with some difficulty as the Cabotia was at almost the extreme range for my old-fashioned transmitter, and the reply some time later gave the captain the needed know-how to keep John alive until we arrived at the ‘Tail of the Bank’ at Greenock, where he was rushed ashore. I am glad to say we heard later that he survived his ordeal. Since those days the medical service to ships at sea has improved out of all recognition, and telegrams prefixed ‘Medico’ and preceded by the urgency signal now take precedence over everything except distress traffic. I was to handle much of this kind of traffic in the years to come and can honestly say without any conceit that I saved some lives. It is often forgotten that our somewhat despised profession was to become the main prop in the continuing fight over the ages for ‘The safety of life at sea’.

In the early days of which I am speaking, this fact had not yet sufficiently sunk in and many shipowners would gladly have foregone this safety in their almost vicious campaign to be rid of the expense involved in paying for a ships radio station and operator. I am not sure of the date on which the carrying of wireless on ships became compulsory and the whole concept was fought against bitterly by many of Britain’s rogue shipowners, and even by governments.

In the twenties there were strong lobbies in Parliament representing shipping interests, and there were always a considerable number of ship-owners in the ranks of the MPs, and of course in the House of Lords. It was a pity for everybody concerned that the scamp ship-owners in the persons of Walter Runciman, Joseph McLay, R. P. Houston, and Sir Burton Chadwick were to hold governmental high position during the time that ‘safety of life at sea’ was struggling for recognition.

Chadwick, a ship-owner and ex master mariner held the post of President of the Board of Trade for a time, a position he was eminently unfitted for. At a crisis point in the shipping industry when overloaded tramp ships were foundering with monotonous regularity there was an all out onslaught by Chadwick on this ‘new profession that was unwanted and had no part in the traditions of the sea’, meaning the radio officer. As head of the BOT and the final arbiter of the destiny and fate of British shipping at that time he held a terrible responsibility.

The traditions of the sea of which he so glibly spoke had little to do with men like him who had so soon forgotten that seven hundred lives were saved by wireless from the Titanic not all that many years earlier. The wireless man there partially made up for the utter failure of the navigator to keep his ship afloat and that kind of thing has been going on ever since.

The highest decoration for heroism at sea, the George Cross, is held, to the best of my knowledge, by only one Merchant Navy officer and he is not a navigator or engineer. He is David Broadfoot, Radio Officer of the ‘Princess Victoria’.

CONTINUED NEXT MONTH

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item