This is the story of the MV Skyluck and its notorious voyage from Vietnam to Hong Kong with a human cargo. Was it a voyage of compassion or a voyage of infamy?

To my way of thinking there is a decided difference between rescuing refugees at sea, in distress, and that of planning, embarking, and executing a voyage carrying a human cargo of refugees in such high numbers, in such deplorable conditions as it poses a distinct danger to both vessel and all those onboard. The latter can only be categorized as a voyage of infamy.

So was the voyage of the aging Panamanian freighter Skyluck, deliberately designated by its owners to carry refugees from Vietnam to Hong Kong. The owner and CEO of Skyluck, which incidentally was the largest shipping company in South Vietnam at the time, had escaped Vietnam just prior to its collapse, in one of his other company ships, but he had left instructions to his devoted employees to evacuate as many refugees as they could in the Line’s remaining vessels. His company had made a fortune by re-supplying the American forces with all kinds of cargo needed to pursue the war against the communist North Vietnamese.

Of course, there were many ships that rescued Vietnamese refugees at sea in an entirely proper way, such as the Clara Maersk and Sibonga, amongst many others. Being an ex-ship master myself, I too would never hesitate to offer assistance and attempt to rescue any soul at sea in distress, but the case of the Skyluck, it can only be classified as shameful due to the stealthy manner in which the voyage from Vietnam was executed, albeit intended as a humanitarian gesture at the time, but with full knowledge that the fate of those onboard was at the best hazardous and uncertain. However, there are those that would argue that the fate of the refugees was also hazardous and uncertain if they had remained in Vietnam once the Americans had withdrawn following the surrender to the North Vietnamese forces.

On 30th April Saigon, the capital city of South Vietnam, fell to the communist North, and the prolonged American intervention in Vietnam ceased, drawing the war to a close. The following year, Saigon would be renamed Ho Chi Minh City after the North’s late revolutionary leader. The capitulation of Saigon triggered intense hardship for those Vietnamese and Chinese from the south. By 1978, however, the trickle of boat people seeking political asylum and resettlement had become one of epic proportions. During 1979, more than the total number of refugees that arrived in Hong Kong in 1975 landed in the territory in a single day. This was largely due to the forced socialist restructuring of industry and harassment of Vietnam’s ethnic Chinese population, who had historically dominated commerce, especially in the South. In March 1978, all trade and business operations of Vietnamese Chinese traders was abolished in Vietnam, and tens of thousands of private enterprises closed in one “swoop”.

In the initial years immediately after 1975, Vietnamese authorities would endeavour to stop all Vietnamese fleeing the country by boat, but by 1978, regime officials were accepting illicit payments and bribes to look the other way. The virtually bankrupt Vietnamese Government not only encouraged the clandestine migration to rid themselves of the unwanted Chinese Vietnamese, but also saw the opportunity for large scale profiteering in the human trade. Despite denials from Vietnam, it was now widely accepted that the communist government, supported by triad gangs, was encouraging the exodus of Chinese Vietnamese citizens, exploiting their significant financial resources, and trading in human misery.

The harsh treatment, as well as economic hardship and food shortages, drove many Chinese Vietnamese to risk escape by boat, often in rundown fishing boats entirely unfit and in most cases unseaworthy for long sea voyages, seeking to find sanctuary in Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia. Many did not survive the passage, due to storms and shipwreck, the scourge of savage pirate attacks, and starvation. It opened the way for what is today known as “people smuggling”.

The Hong Kong Government had a policy of refusing to let the refugees who had arrived on ships illegally, land in the territory. Rather, they kept the refugees confined on the overcrowded ships. This policy was, in part, as a deterrent to other would be “Boat People” arriving from Vietnam, since Hong Kong was already very densely populated and could not cope with any massive influx of refugees. The arrival of illegals, all be that they fleeing possible persecution from the Vietnamese communist regime, had already started to arrive in considerable numbers prior to Skyluck, creating even more strain on the Hong Kong Government to accommodate, feed, and manage such numbers.

Skyluck (IMO: 5384724) was a General Cargo Ship that was built in 1951 by Robb Caledon at Leith, originally for the iconic New Zealand firm of the Union Steamship Company. She was of 3,506 grt and 5,321 dwt, with a length overall of 105.3m and beam 15.3m. Her port of registry was Panama. Formerly, she had been launched as the Kurutai but entered service as the Waimate (until 1972), and Eastern Planet (until 1977), before being sold to Panamanian interests and renamed Skyluck.

Reportedly, an adult would need to pay, on average, 10 to 12 taels of 24k gold for a passage on an escape ship (one tael being 1.2 troy ounces). The fee for children was determined by their age. The price of gold in January 1979 was about US$240 an ounce, so the cost for an adult would be around US$3,000, today’s equivalent being more than US$10,000, for a risky passage in a floating hulk to the unknown. Colluding with international and triad syndicates, communist Vietnamese authorities became complicit in people smuggling on a massive scale, with oceangoing freighters from unscrupulous owners seeking fast immoral profits, chartered to make the exodus as profitable as possible for the people smuggling syndicates. Hence, the value of transporting the refugees in monetary terms can easily be calculated.

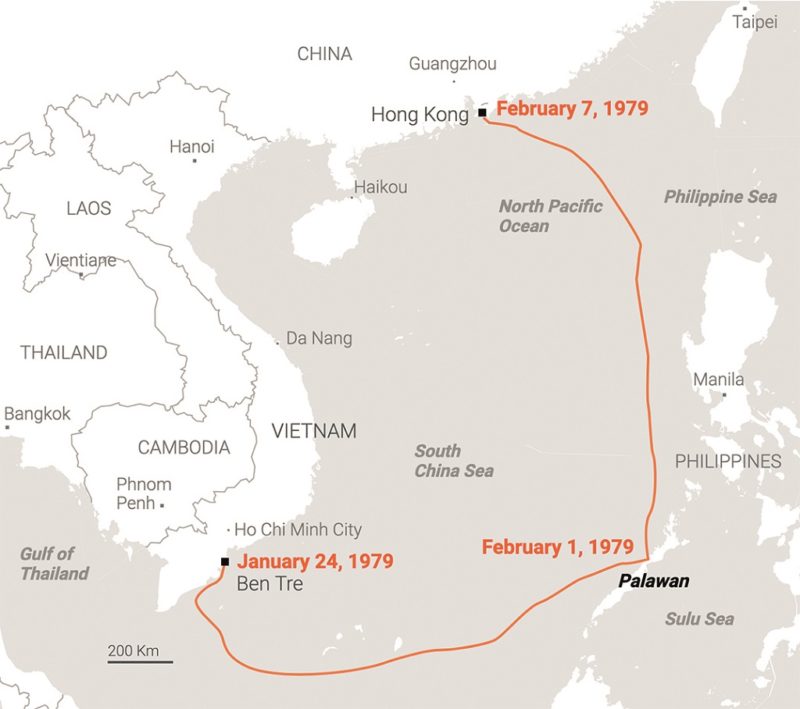

One ship used for human trafficking was a rusting vessel called the Skyluck, which departed from the Mekong Delta in January 1979, crammed with Vietnamese refugees, embarked from boats whilst she was anchored. She then proceeded towards the Philippines, but after an attempt to offload its human cargo in the Philippines had been thwarted, the angry passengers demanded that the captain take them to Hong Kong.

Hence, the Skyluck slipped stealthily and unannounced into Victoria Harbour in the early hours of 7th February 1979, arriving with 2,600 Chinese Vietnamese boat people fleeing Vietnam, some four years after the fall of Saigon.

The Skyluck, upon arrival at Hong Kong was boarded by the Hong Kong Police due to a reported disturbance onboard and what they found was thousands of illegal boat people fleeing Vietnam. The captain was reportedly tied up and guarded by two refugees to make it appear he was acting under duress.

A check of the movements of the Hong Kong Marine Department and Hong Kong Police as to the voyage history of the vessel, ultimately revealed she had sailed from Singapore on 12th January with the first port of call declared as Hong Kong. However, the Hong Kong Marine Department was skeptical and investigated further. It was finally ascertained, after sailing from Singapore, the ship had diverted and sailed to South Vietnam, anchoring off the Mekong Delta to collect her human cargo. The letters S, C, and K had been removed from her name (KYLU), to avoid recognition and detection. It was only after embarking her illicit cargo was the correct ship’s name reinstated. She had arrived in the Philippines, but her entry was rejected. The captain, reportedly under duress from the refugees, then sailed to Hong Kong. This accounted for the lapsed 27 days between departing Singapore and arrival in Hong Kong.

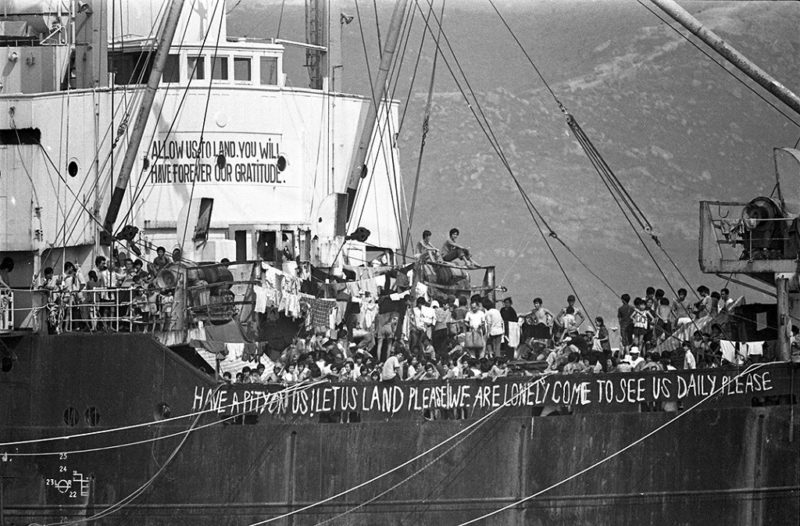

The newly arrived refugees were in bad shape, angry, almost starving and in some cases sick (above). The priority of the Hong Kong Government was to provide humanitarian aid by way of food, water, and medical attention, etc. However, the refugees were not permitted to disembark and were quarantined onboard the ship. Described by some as being a “floating wreck” the Hong Kong Marine Department directed the ship to an anchorage in the West Lamma Channel, between Lamma and Cheung Chau Island.

A temporary landing pontoon was secured alongside the Skyluck to facilitate boats coming alongside every couple of days, to provided fresh provisions. The refugees, who knew they were in the focus of the media, also took to creating banners and painting slogans on the ship’s side, in attempts to promote their claim for political asylum and freedom.

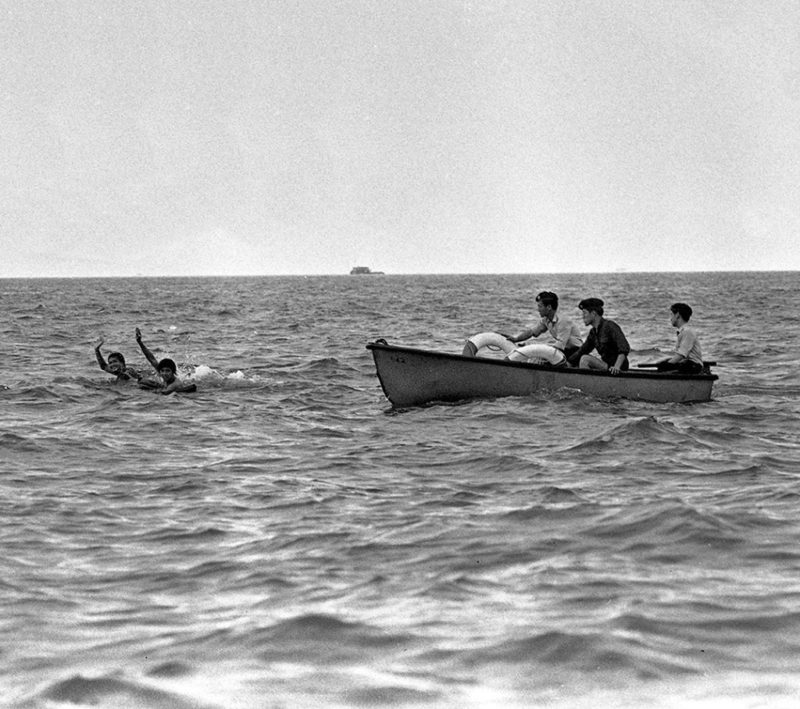

In their frustration, some refugees jumped overboard into the sea attempting to swim to the nearby islands but were soon recovered by police motor launches which returned the swimmers back onboard Skyluck (above). Following the various swimming incidents, the Skyluck was towed further offshore. Once under the control of the Hong Kong Government the food supply was well managed and became pretty good for all those onboard

Refugees arriving in Hong Kong usually expected to be held onboard the ship for some days. It was standard operating procedure for boat people arriving in Hong Kong to be kept at anchorage for a week, effectively quarantined at sea, to permit time for the authorities to screen and process the illegal arrivals. But in this case, due to the Skyluck having entered the harbour illegally and covertly, thereby causing embarrassment to those responsible with countering such arrivals, the refugees were informed on 9th February 1979, that they would not be allowed to land any time soon. While the Skyluck was guarded by patrolling Police launches to ensure refugees did not abscond, the Police presence also kept journalists and the curious away from the ship. This lack of communication with the outside world led to a belief among refugees that they were being deliberately expunged from the headlines.

With such overcrowding and deplorable conditions onboard, maintaining hygiene on the Skyluck was a struggle. With so many unwashed bodies in close quarters the air was foul, nauseating, dank, and impregnated with the stench of diesel oil, rust, sweat and worse, even excrement. Refugees had only two litres of water for each person per day, which prevented them from washing properly. The odour of unwashed human bodies was overpowering.

So began an impasse that would last for almost five months which even triggered a short hunger strike amongst some refugees onboard, but to no avail, with the Hong Kong Government refusing to budge on their position regarding the eligibility of those onboard to gain refugee status, and disembark.

Finally, in late June, the frustrated refugees, their tempers fraying, and patience stretched beyond normal limitations, took matters into their own hands. They decided to cut and slip the anchor chains in the hope the vessel would drift to one of the near islands and beach itself.

On the night of 28th June, with military like precision, refugees were organized into teams. There was a team for cutting the two anchor chains and a security detail to protect the cutters from other refugees, in case there was physical opposition to the action. A group was tasked with repelling police once the Skyluck was free of its moorings and adrift, and a team to oversee evacuation of the ship in case of any accident resulting from these actions.

By about 9am on 29th June, however, stormy clouds were gathering. A storm was imminent. With favourable wind and tide the refugees cut the two retaining ropes to the anchor chains and the vessel was adrift. Once the Marine Police ascertained what was happening the alarm was raised and numerous tugs, reinforcements and a variety of craft were deployed to try to guide the vessel towards deep water, but as the boats came close to Skyluck the refugees pelted the police boats with Molotov cocktails to keep them at bay. Initially the vessel drifted towards Chung Chau but then, due to strong tide and winds, she drifted back towards Lamma. Eventually its portside grounded heavily with the rocky shoreline at Shek Kok Tsui, north of Yung Shue Wan village. The grounding immediately caused the engine room to flood and the ship was doomed. The refugees became elated.

During the resulting euphoria onboard, cargo nets, ropes, and ladders were thrown over the ship’s side, and many of the younger men, caught up in the delirium of the moment, immediately made for land, some running for the hills. But quickly they realized there was nowhere to go and were soon rounded up by police and reinforcements from the British army.

During the course of the day, the refugees were shuttled on boats from Yung Shue Wan to a temporary detention centre, formerly an open prison, on Lantau’s Chi Ma Wan peninsula. Chi Ma Wan was only a temporary location for the refugees from the Skyluck and within weeks they were relocated to more established holding camps, with many heading to the Jubilee Transit Centre in Sham Shui Po, which was an open camp, run in collaboration with the UNHCR. According to government figures, Hong Kong took in 68,784 boat people in 1979 alone.

Following years of detention, most of the refugees were granted full refugee status and relocated, mainly to the USA and some to Australia, they having been the two main participating nations in the Vietnam War. Others were taken by Britain, Canada, France, and Germany.

According to the UNHCR, it has been estimated 800,000 fled Vietnam by boat, and that a further 200,000 to 400,000 were lost at sea in their attempts to seek freedom from the communist state.

Having been seized by authorities but abandoned for months off Lamma, in December 1979 the ship was sold for demolition, for a reported HK$500,000. The breached hull plates were temporarily patched, and on 14th May 1980, the salvaged vessel was towed to the main ship-breaking yard at Junk Bay, where it met its demise. The Danish freighter Clara Maersk was the first vessel to trigger Hong Kong’s involvement with Vietnamese boat people, when she rescued 3,743 Vietnamese boat people at sea in distress in May 1975. This was a normal sea rescue under the terms of the law of the sea.

On an earlier and more infamous footing, in December 1978, a Panamanian vessel the Huey Fong (above) sailed from Vietnam with 3,318 refugees onboard. It was purportedly bound for Kaohsiung. Whilst at sea the master radioed the Hong Kong Marine Department saying that he had picked up thousands of refugees in the South China Sea, found in leaking junks. The master asked for permission to enter Hong Kong. Permission was refused. However, this was disregarded by the master and the vessel anchored about one mile outside Hong Kong territorial waters while the world media watched. The master was offered assistance to enable the vessel to continue its voyage, but this offer was declined. The impasse continued. In mid-January 1979 the master was told that the government would not continue to supply provisions indefinitely and he should continue his voyage to Kaohsiung. The next day the Huey Fong entered the port of Hong Kong without permission, and the refugees disembarked and were given accommodation ashore, for humanitarian reasons.

The captain of the Huey Fong and 10 others, including three Hong Kong-based businessmen with Vietnamese connections, were charged and convicted of conspiracy. The trial evidence revealed that the refugees had embarked in Vietnamese waters with the assistance of the local authorities, and the ship’s log had been falsified. In the engine-room of the Huey Fong, HK$6.5 million worth of gold was found concealed and hidden away, clear evidence that the vessel was engaged in trafficking in human cargo.

Some of the better-known vessels involved in people smuggling, carrying refugees from Vietnam were the Southern Cross, 1,252 passengers in September 1978, landing at Bintan Island, Indonesia, Hai Hong, 2,504 passengers in November 1978 landing at Port Klang, Malaysia, Tung An, 2,300 passengers in January 1979 landing at Manila Bay, Philippines (above).

No doubt there were many other unknown vessels which engaged in the scandalous trade of human suffering and misery. Many boats were likely to have foundered at sea causing the tragic loss of life.

All photos from the South China Morning Post unless otherwise stated

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item